Posts Tagged ‘Trust-based approach’

Serious Business

If you’re serious about your work, you’re too serious. We’re all too bound up in this life-or-death, gotta-meet-the-deadline nonsense that does nothing but get in the way.

If you’re serious about your work, you’re too serious. We’re all too bound up in this life-or-death, gotta-meet-the-deadline nonsense that does nothing but get in the way.

If you’re into following recipes, I guess it’s okay to be held accountable to measuring the ingredients accurately and mixing the cake batter with 110% effort. When your business is serious about making more cakes than anyone else on the planet, it’s fine to take that seriously. But if you’re into making recipes, serious doesn’t cut it. Coming up with new recipes demands the freedom of putting together spices that have never been combined. And if you’re too serious, you’ll never try that magical combination that no one else dared.

Serious is far different than fully committed and “all in.” With fully committed, you bring everything you have, but you don’t limit yourself by being too serious. When people are too serious they pucker up and do what they did last time. With “all in” it’s just that – you put all your emotional chips on the line and you tell the dealer to “hit.” If the cards turn in your favor you cash in in a big way. If you bust, you go home, rejuvenate and come back in the morning with that same “all in” vigor you had yesterday and just as many chips. When you’re too serious, you bet one chip at a time. You don’t bet many chips, so you don’t lose many. But you win fewer.

The opposite of serious is not reckless. The opposite of serious is energetic, extravagant, encouraging, flexible, supportive and generous. A culture of accountability is serious. A culture of creativity is not.

I do not advocate behavior that is frivolous. That’s bad business. I do advocate behavior that is daring. That’s good business. Serious connotes measurable and quantifiable, and that’s why big business and best practices like serious. But measurable and quantifiable aren’t things in themselves. If they bring goodness with them, okay. But there’s a strong undercurrent of measurable for measurable’s sake. It’s like we’re not sure what to do, so we measure the heck out of everything. Daring, on the other hand, requires trust is unmeasurable. Never in the history of Six Sigma has there been a project done on daring and never has one of its control strategies relied on trust. That’s because Six Sigma is serious business. Serious connotes stifling, limiting and non-trusting, and that’s just what we don’t need.

Let’s face it, Six Sigma and lean are out of gas. So is tightening-the-screws management. The low hanging fruit has been picked and Human Resources has outed all the mis-fits and malcontents. There’s nothing left to cut and no outliers to eliminate. It’s time to put serious back in its box.

I don’t know what they teach in MBA programs, but I hope it’s trust. And I don’t know if there’s anything we can do with all our all-too-serious managers, but I hope we put them on a program to eliminate their strengths and build on their weaknesses. And I hope we rehire the outliers we fired because they scared all the serious people with their energy, passion and heretical ideas.

When you’re doing the same thing every day, serious has a place. When you’re trying to create the future, it doesn’t. To create the future you’ve got to hire heretics and trust them. Yes, it’s a scary proposition to try to create the future on the backs of rabble-rousers and rebels. But it’s far scarier to try to create it with the leagues of all-too-serious managers that are running your business today.

Image credit — Alan

A Life Boat in the Sea of Uncertainty

Work is never perfect, family life is never perfect and neither is the interaction between them. Regardless of your expectations or control strategies, things go as they go. That’s just what they do.

Work is never perfect, family life is never perfect and neither is the interaction between them. Regardless of your expectations or control strategies, things go as they go. That’s just what they do.

We have far less control than we think. In the pure domain of physics the equations govern predictively – perturb the system with a known input in a controlled way and the output is predictable. When the process is followed, the experimental results repeat, and that’s the acid test. From a control standpoint this is as good as it gets. But even this level of control is more limited than it appears.

Physical laws have bounded applicability – change the inputs a little and the equation may not apply in the same way, if at all. Same goes for the environment. What at the surface looks controllable and predictable, may not be. When the inputs change, all bets are off – the experimental results from one test condition may not be predictive in another, even for the simplest systems, In the cold, unemotional world of physical principles, prediction requires judgement, even in lab conditions.

The domains of business and life are nothing like controlled lab conditions. And they’re and not governed by physical laws. These domains are a collection of complex people systems which are governed by emotional laws. Where physics systems delivers predictable outputs for known inputs, people systems do not. Scenario 1. Your group’s best performer is overworked, tired, and hasn’t exercised in four weeks. With no warning you ask them to take on an urgent and important task for the CEO. Scenario 2. Your group’s best performer has a reasonable workload (and even a little discretionary time), is well rested and maintains a regular exercise schedule, and you ask for the same deliverable in the same way. The inputs are the same (the urgent request for the CEO), the outputs are far different.

At the level of the individual – the building block level – people systems are complex and adaptive, The first time you ask a person to do a task, their response is unpredictable. The next day, when you ask them to do a different task, they adapt their response based on yesterday’s request-response interaction, which results in a thicker layer of unpredictability. Like pushing on a bag of water, their response is squishy and it’s difficult to capture the nuance of the interaction. And it’s worse because it takes a while for them to dampen the reactionary waves within them.

One person interacts with another and groups react to other groups. Push on them and there’s really no telling how things will go. One cylo competes with another for shared resources and complexity is further confounded. The culture of a customer smashes against your standard operating procedures and the seismic pressure changes the already unpredictable transfer functions of both companies. And what about the customer that’s also your competitor? And what about the big customer you both share? Can you really predict how things will go? Do you really have control?

What does all this complexity, ambiguity, unpredictability and general lack of control mean when you’re trying to build a culture of accountability? If people are accountable for executing well, that’s fine. But if they’re held accountable for the results of those actions, they will fail and your culture of accountability will turn into a culture of avoiding responsibility and finding another place to work.

People know uncertainty is always part of the equation, and they know it results in unpredictability. And when you demand predictability in a system that’s uncertain by it’s nature, as a leader you lose credibility and trust.

As we swim together in the storm of complexity, trust is the life boat. Trust brings people together and makes it easier to row in the same direction. And after a hard day of mistakenly rowing in the wrong direction, trust helps everyone get back in the boat the next day and pull hard in the new direction you point them.

Image credit – NASA

It’s time to make a difference.

If on the first day on your new job your stomach is all twisted up with anxiety and you’re second guessing yourself because you think you took a job that is too big for you, congratulations. You got it right. The right job is supposed to feel that way. If on your first day you’re totally comfortable because you’ve done it all before and you know how it will go, you took the job for the money. And that’s a terrible reason to take a job.

If on the first day on your new job your stomach is all twisted up with anxiety and you’re second guessing yourself because you think you took a job that is too big for you, congratulations. You got it right. The right job is supposed to feel that way. If on your first day you’re totally comfortable because you’ve done it all before and you know how it will go, you took the job for the money. And that’s a terrible reason to take a job.

You got the job because someone who knew what it would take to get it done believed you were the right one to do just that. This wasn’t charity. There was something in it for them. They needed the job done and they wanted a pro. And they chose you. The fact their stomach isn’t in knots says nothing about their stomach and everything about their belief in you. And the knots in your stomach? That ‘s likely a combination of immense desire to do a good job and an on-the-low-side belief in yourself.

If we’re not stretching we’re not learning, and if we’re not learning we’re not living. So why the nerves? Why the self doubt? Why don’t we believe in ourselves? When we look inside, we see ourselves in the moment – in the now, as we are. And sometimes when we look inside there are only re-run stories of our younger selves. It’s difficult to see our future selves, to see our own growth trajectory from the inside. It’s far easier to see a growth trajectory from the outside. And that’s what the hiring team sees – our future selves – and that’s why they hire.

This growth-stretch, anxiety-doubt seesaw is not unique to new jobs. It’s applicable right down the line – from temporary assignments, big projects and big tasks down to small tasks with tight deliverables. If you haven’t done it before, it’s natural to question your capability. But if you trust the person offering the job, it should be natural to trust their belief in you.

When you sit in your new chair for the first time and you feel queasy, that’s not a sign of incompetence it’s a sign of significance. And it’s a sign you have an opportunity to make a difference. Believe in the person that hired you, but more importantly, believe in yourself. And go make a difference.

Image credit – Thomas Angermann

To make a difference, add energy.

If you want to make a difference, you’ve got to add energy. And the more you can add the bigger difference you can make.

If you want to make a difference, you’ve got to add energy. And the more you can add the bigger difference you can make.

Doing new is difficult and demands (and deserves) all the energy you can muster. Often it feels you’re the only one pushing in the right direction while everyone else is vehemently pushing the other way. But stay true and stand tall. This is not an indication things are going badly, this is a sign you’re doing meaningful work. It’s supposed to feel that way. If you’re exhausted, frustrated and sometimes a bit angry, you’re doing it right. If you have a healthy disrespect for the status quo, it’s supposed to feel that way.

Meaningful work has a long time constant and you’ve got to run these meaningful projects like marathons, uphill marathons. Every day you put in your 26 miles at a sustainable pace – no slower, but no faster. This is long, difficult work that doesn’t run by itself, you’ve got to push it like a sled. Every day you’ve got to push. To push every day like this takes a lot of physical strength, but it takes even more mental strength. You’ve got to stay focused on the critical path and push that sled every day. And you need to preserve enough mental energy to effectively ignore the non-critical path sleds. You’ve got to be able to decide which tasks you must get your whole body behind and which tasks you must discount. And you’ve got to preserve enough energy to believe in yourself.

Meaningful work cannot be accomplished by sprinting full speed five days a week. It’s a marathon, and you’ve got to work that way and train that way. Get your rest, get your exercise, eat right, spend time with friends and family, and put your soul into your work.

Choose work that is meaningful and add energy. Add it every day. Add it openly. Add it purposefully. Add it genuinely. Add energy like you’re an aircraft carrier and others will get pulled along by your wake. Add energy like you’re bulldozer and others will get out of your way. Add energy like you’re contagious and others will be infected.

Image credit – anton borzov

The People Business

Things don’t happen on their own, people make them happen.

With all the new communication technologies and collaboration platforms it’s easy to forget that what really matters is people. If people don’t trust each other, even the best collaboration platforms will fall flat, and if they don’t respect each other, they won’t communicate – even with the best technology.

Companies put stock in best practices like they’re the most important things, but they’re not. Because of this unnatural love affair, we’re blinded to the fact people are what make best practices best. People create them, people run them, and people improve them. Without people there can be no best practices, but on the flip-side, people can get along just fine without best practices. (That says something, doesn’t it?) Best practices are fine when processes are transactional, but few processes are 100% transactional to the core, and the most important processes are judgement-based. In a foot race between best practices and good judgement, I’ll take people and their judgment – every day.

Without a forcing function, there can be no progress, and people are the forcing function. To be clear, people aren’t the object of the forcing function, they are the forcing function. When people decide to commit to a cause, the cause becomes a reality. The new reality is a result – a result of people choosing for themselves to invest their emotional energy. People cannot be forced to apply their life force, they must choose for themselves. Even with today’s “accountable to outcomes” culture, the power of personal choice is still carries the day, though sometimes it’s forced underground. When pushed too hard, under the cover of best practice, people choose to work the rule until the clouds of accountability blow over.

When there’s something new to do, processes don’t do it – people do. When it’s time for some magical innovation, best practices don’t save the day – people do. Set the conditions for people to step up and they will; set the conditions for them to make a difference and they will. Use best practices if you must, but hold onto the fact that whatever business you’re in, you’re in the people business.

Image credit – Vicki & Chuck Rogers

Systematic Innovation

Innovation is a journey, and it starts from where you are. With a systematic approach, the right information systems are in place and are continuously observed, decision makers use the information to continually orient their thinking to make better and faster decisions, actions are well executed, and outcomes of those actions are fed back into the observation system for the next round of orientation. With this method, the organization continually learns as it executes – its thinking is continually informed by its environment and the results of its actions.

Innovation is a journey, and it starts from where you are. With a systematic approach, the right information systems are in place and are continuously observed, decision makers use the information to continually orient their thinking to make better and faster decisions, actions are well executed, and outcomes of those actions are fed back into the observation system for the next round of orientation. With this method, the organization continually learns as it executes – its thinking is continually informed by its environment and the results of its actions.

To put one of these innovation systems in place, the first step is to define the group that will make the decisions. Let’s call them the Decision Group, or DG for short. (By the way, this is the same group that regularly orients itself with the information steams.) And the theme of the decisions is how to deploy the organization’s resources. The decision group (DG) should be diverse so it can see things from multiple perspectives.

The DG uses the company’s mission and growth objectives as their guiding principles to set growth goals for the innovation work, and those goals are clearly placed within the context of the company’s mission.

The first action is to orient the DG in the past. Resources are allocated to analyze the product launches over the past ten years and determine the lines of ideality (themes of goodness, from the customers’ perspective). These lines define the traditional ideality (traditional themes of goodness provided by your products) are then correlated with historical profitability by sales region to evaluate their importance. If new technology projects provide value along these traditional lines, the projects are continuous improvement projects and the objective is market share gain. If they provide extreme value along traditional lines, the projects are of the dis-continuous improvement flavor and their objective is to grow the market. If the technology projects provide value along different lines and will be sold to a different customer base, the projects could be disruptive and could create new markets.

The next step is to put in place externally focused information streams which are used for continuous observation and continual orientation. An example list includes: global and regional economic factors, mergers/acquisitions/partnerships, legal changes, regulatory changes, geopolitical issues, competitors’ stock price and quarterly updates, and their new products and patents. It’s important to format the output for easy visualization and to make collection automatic.

Then, internally focused information streams are put in place that capture results from the actions of the project team and deliver them, as inputs, for observation and orientation. Here’s an example list: experimental results (technology and market-centric), analytical results (technical and market), social media experiments, new concepts from ideation sessions (IBEs), invention disclosures, patent filings, acquisition results, product commercialization results and resulting profits. These information streams indicate the level of progress of the technology projects and are used with the external information streams to ground the DG’s orientation in the achievements of the projects.

All this infrastructure, process, and analysis is put in place to help the DG make good (and fast) decisions about how to allocate resources. To make good decisions, the group continually observes the information streams and continually orients themselves in the reality of the environment and status of the projects. At this high level, the group decides not how the project work is done, rather what projects are done. Because all projects share the same resource pool, new and existing projects are evaluated against each other. For ongoing work the DG’s choice is – stop, continue, or modify (more or less resources); and for new work it’s – start, wait, or never again talk about the project.

Once the resource decision is made and communicated to the project teams, the project teams (who have their own decision groups) are judged on how well the work is executed (defined by the observed results) and how quickly the work is done (defined by the time to deliver results to the observation center.)

This innovation system is different because it is a double learning loop. The first one is easy to see – results of the actions (e.g., experimental results) are fed back into the observation center so the DG can learn. The second loop is a bit more subtle and complex. Because the group continuously re-orients itself, it always observes information from a different perspective and always sees things differently. In that way, the same data, if observed at different times, would be analyzed and synthesized differently and the DG would make different decisions with the same data. That’s wild.

The pace of this double learning loop defines the pace of learning which governs the pace of innovation. When new information from the streams (internal and external) arrive automatically and without delay (and in a format that can be internalized quickly), the DG doesn’t have to request information and wait for it. When the DG makes the resource-project decisions it’s always oriented within the context of latest information, and they don’t have to wait to analyze and synthesize with each other. And when they’re all on the same page all the time, decisions don’t have to wait for consensus because it already has. And when the group has authority to allocate resources and chooses among well-defined projects with clear linkage to company profitability, decisions and actions happen quickly. All this leads to faster and better innovation.

There’s a hierarchical set of these double learning loops, and I’ve described only the one at the highest level. Each project is a double learning loop with its own group of deciders, information streams, observation centers, orientation work and actions. These lower level loops are guided by the mission of the company, goals of the innovation work, and the scope of their projects. And below project loops are lower-level loops that handle more specific work. The loops are fastest at the lowest levels and slowest at the highest, but they feed each other with information both up the hierarchy and down.

The beauty of this loop-based innovation system is its flexibility and adaptability. The external environment is always changing and so are the projects and the people running them. Innovation systems that employ tight command and control don’t work because they can’t keep up with the pace of change, both internally and externally. This system of double loops provides guidance for the teams and sufficient latitude and discretion so they can get the work done in the best way.

The most powerful element, however, is the almost “living” quality of the system. Over its life, through the work itself, the system learns and improves. There’s an organic, survival of the fittest feel to the system, an evolutionary pulse, that would make even Darwin proud.

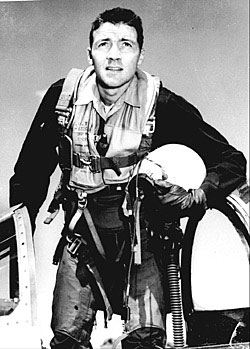

But, really, it’s Colonel John Boyd who should be proud because he invented all this. And he called it the OODA loop. Here’s his story – Boyd: The Fighter Pilot Who Changed the Art of War.

Where possible, I have used Boyd’s words directly, and give him all the credit. Here is a list of his words: observe, orient, decide, act, analyze-synthesize, double loop, speed, organic, survival of the fittest, evolution.

Image attribution – U.S. Government [public domain]. by wikimedia commons.

The Prerequisites for Greatness

There are three prerequisites for greatness.

There are three prerequisites for greatness.

- You have to believe greatness is possible.

- You have to believe greatness is worth it.

- You have to believe you’re worthy of the journey.

If you can’t see old things in new ways, see new things in new ways, or see what’s missing, you won’t believe greatness is possible. To believe greatness is possible, you have to change your perspective.

Greatness is an uphill battle on all fronts, and to push through the pain requires weapons grade belief that it’s worth it. But the power isn’t in the payoff. The power is the personal meaning you attach to the work. Your slog toward greatness is powered from the inside out.

Here’s the tough one – you’ve got to believe you’re worthy of the journey. At every turn the status quo will kick you in the shins, and you must strap on your self-worth like shin guards. And when it’s time to conger greatness from gravel, you must believe, somehow, your life force will rise to the occasion. But, to be clear, you don’t have to believe you’ll be successful; you only have to believe you’re worth the bet.

From the outside, greatness is all about the work. But from the inside, greatness is all about you.

Image credit – Dietmar Temps

What’s your innovation intention?

If you want to run a brainstorming session to generate a long list of ideas, I’m out. Brainstorming takes the edge off, rounds off the interesting corners and rubs off any texture. If you want me to go away for a while and come back with an idea that can dismantle our business model, I’m in.

If you want to run a brainstorming session to generate a long list of ideas, I’m out. Brainstorming takes the edge off, rounds off the interesting corners and rubs off any texture. If you want me to go away for a while and come back with an idea that can dismantle our business model, I’m in.

If you can use words to explain it, don’t bother – anything worth its salt can’t be explained with PowerPoint. If you need to make a prototype so others can understand, you’ve got my attention.

If you have to ask my permission before you test out an idea that could really make a difference, I don’t want you on my team. If you show me a pile of rubble that was your experiment and explain how, if it actually worked, it could change the game, I’ll run air cover, break the rules, and jump in front of the bullets so you can run your next experiments, whatever they are.

If you load me up to with so many projects I can’t do several I want, you’ll get fewer of yours. If you give me some discretion and a little slack to use it, you’ll get magic.

If, before the first iteration is even drawn up, you ask me how much it will cost, I will tell you what you want to hear. If, after it’s running in the lab and we agree you’ll launch it if I build it, I won’t stop working until it meets your cost target.

If there’s total agreement it’s a great idea, it’s not a great idea, and I’m out. If the idea is squashed because it threatens our largest, most profitable business, I’m in going to make it happen before our competitors do.

If twice you tell me no, yet don’t give me a good reason, I’ll try twice as hard to make a functional prototype and show your boss.

To do innovation, real no-kidding innovation, requires a different mindset both to do the in-the-trenches work and to lead it. Innovation isn’t about following the process and fitting in, it’s about following your instincts and letting it hang out. It’s about connecting the un-connectable using the most divergent thinking. And contrary to belief, it’s not in-the-head work, it’s a full body adventure.

Innovation isn’t about the mainstream, it’s about the fringes. And it’s the same for the people that do the work. But to be clear, it’s not what it may look like at the surface. It’s not divergence for divergence’s sake and it’s not wasting time by investigating the unjustified and the unreasonable. It’s about unique people generating value in unique ways. And at the core it’s all guided by their deep intention to build a resilient, lasting business.

image credit: Chris Martin.

Ratcheting Toward Problems of a Lesser Degree

Here’s how innovation goes:

(Words uttered. // Internal thoughts.)

That won’t work. Yes, this is a novel idea, but it won’t work. You’re a heretic. Don’t bring that up again. // Wow, that scares me, and I can’t go there.

Yes, the first experiment seemed to work, but the test protocol was wrong, and the results don’t mean much. And, by the way, you’re nuts. // Wow. I didn’t believe that thing would ever get off the ground.

Yes, you modified the test protocol as I suggested, but that was only one test and there are lots of far more stressful protocols that surely cannot be overcome. // Wow. They listened to me and changed the protocol as I suggested, and it actually worked!

Yes, the prototype seemed to do okay on the new battery of tests, but there’s no market for that thing. // I thought they were kidding when they said they’d run all the tests I suggested, but they really took my input seriously. And, I can’t believe it, but it worked. This thing may have legs.

Yes, the end users liked the prototypes, but the sample size was small and some of them don’t buy any of our exiting products. I think we should make these two changes and take it to more end users. // This could be exciting, and I want to be part of this.

Yes, they liked the prototypes better once my changes were incorporated, but the cost is too high. // Sweet! They liked my design! I hope we can reduce the cost.

I made some design changes that reduce the cost and my design is viable from a cost standpoint, but manufacturing has other priorities and can’t work on it. // I’m glad I was able to reduce the cost, and I sure hope we can free up manufacting resources to launch my product.

Wow, it was difficult to get manufacturing to knuckle down, but I did it, and my product will make a big difference for the company. // Thanks for securing resources for me, and I’m glad you did the early concept work when I was too afraid.

Yes, my product has been a huge commercial success, and it all strarted with this crazy idea I had. You remember, right? // Thank you for not giving up on me. I know it was your idea. I know I was a stick-in-the-mud. I was scared. And thanks for kindly and effectively teaching me how to change my thinking. Maybe we can do it again sometime.

________________

There’s nothing wrong with this process; in fact, everything is right about it because that’s what people do. We’ve taught them to avoid risk at all costs, and even still, they manage to walk gingerly toward new thinking.

I think it’s important to learn to see the small shifts in attitude as progress, to see the downgrade from an impossible problem to a really big problem as progress.

Instead of grabbing the throat of radical innovation and disrupting yourself, I suggest a waterfall approach of a stepwise ratchet toward problems of a lesser degree. This way you can claim small victories right from the start, and help make it safe to try new things. And from there, you can stack them one on top of another to build your great pyramid of disruption.

And don’t forget to praise the sorceres and heretics who bravely advance their business model-busting ideas without the safety net of approval.

Embrace Uncertainty

There’s a lot of stress in the working world these days, and to me, it all comes down to our blatant disrespect of uncertainty.

There’s a lot of stress in the working world these days, and to me, it all comes down to our blatant disrespect of uncertainty.

In today’s reality, we ask for plans then demand strict adherence to the deliverables – on time, on budget, or else. We treat plans like they’re chiseled in granite, when really it should be more like dry erase markers and a whiteboard. Our markets are uncertain; customers’ behaviors are uncertain; competitors’ actions are uncertain; supply chains are uncertain, yet our plans are plans don’t reflect that reality. And when we expect absolute predictability and accountability, we create stress and anxiety and our people don’t want to try new things because that adds another level of uncertainty.

With a flexible, rubbery plan the first step informs the second, and this is the basis for the logical shift from robust plans to resilient ones. Plans should be less about forcing adherence and more about recognizing deviation. Today’s plans demand early recognition of something that did follow the plan and today’s teams must have the authority to respond quickly. However, after years of denying the powerful force of uncertainty and shooting the messenger, we’ve trained our people to hide the deviations. And, with our culture of control and accountability, our teams require our approval before any type of change, so their response time is, well, not timely.

At our core, we know uncertainty is a founding principle in our universe, and now it’s time to behave that way. It’s time to look inside and decide to embrace uncertainty. Accept it or not, acknowledge it or not, uncertainty is here to stay. Here are some words to guide your journey:

- Resilient not robust.

- Early detection, fast response.

- Many small plans, done in parallel.

- Do more of what works, and less of what doesn’t.

- Plans are meant to be re-planned.

And if you’re into innovation, this applies doubly.

Image credit – dfbphotos.

Difficult Discussions Are The Most Important Discussions

When the train is getting ready to pull out of the station, and you know in your heart the destination isn’t right, what do you do? If you still had time to talk to the conductor, would you? What would you say? If your railroad is so proud of getting to the destination on time it cannot not muster the courage to second guess the well-worn time table, is all hope lost?

When the train is getting ready to pull out of the station, and you know in your heart the destination isn’t right, what do you do? If you still had time to talk to the conductor, would you? What would you say? If your railroad is so proud of getting to the destination on time it cannot not muster the courage to second guess the well-worn time table, is all hope lost?

The trouble with thinking the destination isn’t right is that it’s an opinion. Your opinion may be backed by years of experience, good intuition, and a kind heart, but it’s still an opinion. And the rule with opinions – if there’s one, there are others. And as such, there’s never consensus on the next destination.

But even as the coal is being shoveled into the firebox and the boiler pressure is almost there, there’s still time to take action. If the train hasn’t left the station, there’s still time. Don’t let the building momentum stop you from doing what must be done. Yes, there’s the sunk cost of lining everything up and getting ready to go, but, no, that doesn’t justify a journey down the wrong track. Find the conductor and bend her ear. Be clear, be truthful, and be passionate. Tell her you’re not sure it’s the wrong destination, but you’re sure enough to pull the pressure relieve valve and take some time to think more about what’s about to happen.

No one wants to step in front of a moving train. It’s no fun for anyone, and dangerous for the brave soul standing in the tracks. And it’s a failure of sorts if it comes to that. The best way to prevent a train from heading down the wrong track is candid discussions about the facts and clarity around why the journey should happen. But we need to do a better job at having those tough discussions earlier in the process.

Unfortunately in business today, the foul underbelly of alignment blocks the difficult decisions that should happen. We’ve mapped disagreement to foul play and amoral behavior, and our organizations make it clear that supporting the right answer, right from the get-go, is the right answer. The result is premature alignment and unwarranted alignment without thoughtful, effective debate on the merits. For some reason, it’s no longer okay to disagree.

Difficult discussions are difficult. And prolonging them only makes them more difficult. In fact, that’s sometimes a tactic – push off the tough conversations until the momentum rolls over all intensions to have them.

Hold onto the fact that your company wants the tough conversations to have them. In the short term, things are more stressful, but in the long term thing are more profitable. Remember, though sometimes bureaucracy makes it difficult, you are paid to add your thinking into the mix. And keep in mind you have a valuable perspective that deserves to be valued.

When the train is leaving the station, it’s the easiest time to recognize the tough discussions need to happen but it’s the most difficult time to have them. Earlier in the project it’s easier to have them and far more difficult to recognize they should happen.

Going forward, modify your existing processes to cut through inappropriate momentum building. And better still, use your knowledge of how your organization works to create mechanisms to trigger difficult conversations and prevent premature alignment.

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski