Posts Tagged ‘Product Development Engine’

When doing new work, you’ll be wrong.

When doing something from the first time you’re going to get it wrong. There’s no shame in that because that’s how it goes with new work. But more strongly, if you don’t get it wrong you’re not trying hard enough. And more strongly, embrace the inherent wrongness as a guiding principle.

When doing something from the first time you’re going to get it wrong. There’s no shame in that because that’s how it goes with new work. But more strongly, if you don’t get it wrong you’re not trying hard enough. And more strongly, embrace the inherent wrongness as a guiding principle.

Take Small Bites. With new work, a small scope is better than a large one. But it’s exciting to do new work and there’s a desire to deliver as much novel usefulness as possible. And, without realizing it, the excitement can lead to a project bloated with novelty. With the best intentions, the project team is underwater with too much work and too little time. With new work, it’s better to take one bite and swallow than three and choke.

Ratchet Thinking. With new work comes passion and energy. And though the twins can be helpful and fun to have around, they’re not always well-behaved. Passion can push a project forward but can also push it off a cliff. Energy creates pace and can quickly accelerate a project though the milestones, but energy can be careless and can just as easily accelerate a project in the wrong direction. And that’s where ratchet thinking can help.

As an approach, the objective of ratchet thinking is to create small movements in the right direction without the possibility of back-sliding. Solve a problem and click forward one notch; solve a second problem and click forward another notch. But, with ratchet thinking, if the third problem isn’t solved, the project holds its ground at the second notch. It takes a bit more time to choose the right problem and to solve it in a way that cannot unwind progress, but ultimately it’s faster. Ratchet thinking takes the right small bite, chews, swallows.

Zero Cost of Change. New work is all about adding new functions, enhancing features and fixing what’s broken. In other words, new work is all about change. And the faster change can happen, the faster the product/service/business model is ready for sale. But as the cost of change increases the rate of changes slows. So why not design the project to eliminate the cost of change?

To do that, design the hardware with a bit more capability and headroom so there’s some wiggle room to handle the changes that will come. Use a modular approach for the software to minimize the interactions of software changes and make sure the software can be updated remotely without customer involvement. And put in place a good revision control (and tracking) mechanism.

Doing new work is full of contradictions: move quickly, but take the time to think things through; take on as much as you can, but no more; be wrong, but in the right way; and sometimes slower is faster.

But doing new work you must.

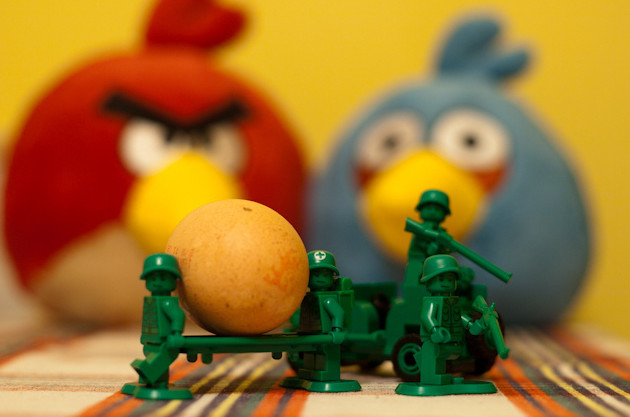

image credit – leasqueaky

If you don’t know the critical path, you don’t know very much.

Once you have a project to work on, it’s always a challenge to choose the first task. And once finished with the first task, the next hardest thing is to figure out the next next task.

Once you have a project to work on, it’s always a challenge to choose the first task. And once finished with the first task, the next hardest thing is to figure out the next next task.

Two words to live by: Critical Path.

By definition, the next task to work on is the next task on the critical path. How do you tell if the task is on the critical path? When you are late by one day on a critical path task, the project, as a whole, will finish a day late. If you are late by one day and the project won’t be delayed, the task is not on the critical path and you shouldn’t work on it.

Rule 1: If you can’t work the critical path, don’t work on anything.

Working on a non-critical path task is worse than working on nothing. Working on a non-critical path task is like waiting with perspiration. It’s worse than activity without progress. Resources are consumed on unnecessary tasks and the resulting work creates extra constraints on future work, all in the name of leveraging the work you shouldn’t have done in the first place.

How to spot the critical path? If a similar project has been done before, ask the project manager what the critical path was for that project. Then listen, because that’s the critical path. If your project is similar to a previous project except with some incremental newness, the newness is on the critical path.

Rule 2: Newness, by definition, is on the critical path.

But as the level of newness increases, it’s more difficult for project managers to tell the critical path from work that should wait. If you’re the right project manager, even for projects with significant newness, you are able to feel the critical path in your chest. When you’re the right project manager, you can walk through the cubicles and your body is drawn to the critical path like a divining rod. When you’re the right project manager and someone in another building is late on their critical path task, you somehow unknowingly end up getting a haircut at the same time and offering them the resources they need to get back on track. When you’re the right project manager, the universe notifies you when the critical path has gone critical.

Rule 3: The only way to be the right project manager is to run a lot of projects and read a lot. (I prefer historical fiction and biographies.)

Not all newness is created equal. If the project won’t launch unless the newness is wrestled to the ground, that’s level 5 newness. Stop everything, clear the decks, and get after it until it succumbs to your diligence. If the product won’t sell without the newness, that’s level 5 and you should behave accordingly. If the newness causes the product to cost a bit more than expected, but the project will still sell like nobody’s business, that’s level 2. Launch it and cost reduce it later. If no one will notice if the newness doesn’t make it into the product, that’s level 0 newness. (Actually, it’s not newness at all, it’s unneeded complexity.) Don’t put in the product and don’t bother telling anyone.

Rule 4: The newness you’re afraid of isn’t the newness you should be afraid of.

A good project plan starts with a good understanding of the newness. Then, the right project work is defined to make sure the newness gets the attention it deserves. The problem isn’t the newness you know, the problem is the unknown consequence of newness as it ripples through the commercialization engine. New product functionality gets engineering attention until it’s run to ground. But what if the newness ripples into new materials that can’t be made or new assembly methods that don’t exist? What if the new materials are banned substances? What if your multi-million dollar test stations don’t have the capability to accommodate the new functionality? What if the value proposition is new and your sales team doesn’t know how to sell it? What if the newness requires a new distribution channel you don’t have? What if your service organization doesn’t have the ability to diagnose a failure of the new newness?

Rule 5: The only way to develop the capability to handle newness is to pair a soon-to-be great project manager with an already great project manager.

It may sound like an inefficient way to solve the problem, but pairing the two project managers is a lot more efficient than letting a soon-to-be great project manager crash and burn. After an inexperienced project manager runs a project into the ground, what’s the first thing you do? You bring in a great project manager to get the project back on track and keep them in the saddle until the product launches. Why not assume the wheels will fall off unless you put a pro alongside the high potential talent?

Rule 6: When your best project managers tell you they need resources, give them what they ask for.

If you want to deliver new value to new customs there’s no better way than to develop good project managers. A good project manager instinctively knows the critical path; they know how the work is done; they know to unwind situations that needs to be unwound; they have the personal relationships to get things done when no one else can; because they are trusted, they can get people to bend (and sometimes break) the rules and feel good doing it; and they know what they need to successfully launch the product.

If you don’t know your critical path, you don’t know very much. And if your project managers don’t know the critical path, you should stop what you’re doing, pull hard on the emergency break with both hands and don’t release it until you know they know.

Image credit – Patrick Emerson

Creating a brand that lasts.

One of the best ways to improve your brand is to improve your products. The most common way is to provide more goodness for less cost – think miles per gallon. Usually it’s a straightforward battle between market leaders, where one claims quantifiable benefit over the other – Ours gets 40 mpg and theirs doesn’t. And the numbers are tied to fully defined test protocols and testing agencies to bolster credibility. Here’s the data. Buy ours

One of the best ways to improve your brand is to improve your products. The most common way is to provide more goodness for less cost – think miles per gallon. Usually it’s a straightforward battle between market leaders, where one claims quantifiable benefit over the other – Ours gets 40 mpg and theirs doesn’t. And the numbers are tied to fully defined test protocols and testing agencies to bolster credibility. Here’s the data. Buy ours

But there’s a more powerful way to improve your brand, and that’s to map your products to reliability. It’s far a more difficult game than the quantified head-to-head comparison of fuel economy and it’s a longer play, but done right, it’s a lasting play that is difficult to beat. Run the thought experiment: think about the brands you associate with reliability. The brands that come to mind are strong, lasting brands, brands with staying power, brands whose products you want to buy, brands you don’t want to compete against. When you buy their products you know what you’re going to get. Your friends tell you stories about their products.

There’s a complete a complete tool set to create products that map to reliability, and they work. But to work them, the commercialization team has to have the right mindset. The team must have the patience to formally define how all the systems work and how they interact. (Sounds easy, but it can be painfully time consuming and the level of detail is excruciatingly extreme.) And they have to be willing to work through the discomfort or developing a common understanding how things actually work. (Sounds like this shouldn’t be an issue, but it is – at the start, everyone has a different idea on how the system works.) But more importantly, they’ve got to get over the natural tendency to blame the customer for using the product incorrectly and learn to design for unintended use.

The team has got to embrace the idea that the product must be designed for use in unpredictable ways in uncontrolled conditions. Where most teams want to narrow the inputs, this team designs for a wider range of inputs. Where it’s natural to tighten the inputs, this team designs the product to handle a broader set of inputs. Instead of assuming everything will work as intended, the team must assume things won’t work as intended (if at all) and redesign the product so it’s insensitive to things not going as planned. It’s strange, but the team has to design for hypothetical situations and potential problems. And more strangely, it’s not enough to design for potential problems the team knows about, they’ve got to design for potential problems they don’t know about. (That’s not a typo. The team must design for failure modes it doesn’t know about.)

How does a team design for failure modes it doesn’t know about? They build a computer-based behavioral model of the system, right down to the nuts, bolts and washers, and they create inputs that represent the environment around the system. They define what each element does and how it connects to the others in the system, capturing the governing physics and propagation paths of connections. Then they purposefully break the functions using various classes of failure types, run the analysis and review the potential causes. Or, in the reverse direction, the team perturbs the system’s elements with inputs and, as the inputs ripple through the design, they find previously unknown undesirable (harmful) functions.

Purposefully breaking the functions in known ways creates previously unknown potential failure causes. The physics-based characterization and the interconnection (interaction) of the system elements generate unpredicted potential failure causes that can be eliminated through design. In that way, the software model helps find potential failures the team did not know about. And, purposefully changing inputs to the system, again through the physics and interconnection of the elements, generates previously unknown harmful functions that can be designed out of the product.

If you care about the long-term staying power of your brand, you may want to take a look at TechScan, the software tool that makes all this possible.

Image credit — Chris Ford.

Is it novel?

Agree or not, companies think they have to grow to survive. (I don’t believe it.) For companies of all sizes and shapes, growth is the single most important forcing function. Is has tidal wave power, and whether you’re a surfer, sailor or power-boater, it’s important to respect it. More than that, when push comes to shove, it’s the only wave in town.

Agree or not, companies think they have to grow to survive. (I don’t believe it.) For companies of all sizes and shapes, growth is the single most important forcing function. Is has tidal wave power, and whether you’re a surfer, sailor or power-boater, it’s important to respect it. More than that, when push comes to shove, it’s the only wave in town.

Companies’ recipe for growth is simple: make more, sell more. And some keep it simpler: sell more.

The best growth: sell new products or provide new services to new customers; next best: sell new to the same customers; next next best: sell more of the same to the same customers. The last flavor is the easiest, right up until it isn’t. And once it isn’t, companies must come up with new things to sell. That works for a while, until it doesn’t. Then, and only then, after exhausting all other possibilities, companies must create real newness and try to sell it to strangers.

The model works well as long as everyone in the industry follows it. But when an up-start outsider enters the market back-to-front, the wheels fall off. When they develop useful newness before you and sell it to your customers (new customers for them), that’s not good. And that’s why it’s so important to start with different — right now.

To help your company do more work that’s different, start with an inventory of your novelty. Novel work is work that creates difference, and that difference can be defined only in comparison with the state-of-the-art (what is, or the baseline system). Start with a functional analysis of your state-of-the-art. Create a block diagram of your business model, your most successful product and the service that defines your brand. Take a look at your technology and new product development projects and flag the ones that will create things that aren’t on your three functional analyses. (Improvement projects, because they improve what is, cannot be flagged as novel.)

Put all your novelty on one page and decide if you like it. (No way around it, how you respond to the level and type of novelty in your quiver is a judgment call.) If you like what you see, keep going. If you don’t, stop some improvement projects and start some projects that create useful novelty. The stopping will not come easy. Existing projects have momentum and people have personal attachment to them. The only thing powerful enough to stop them is the all-powerful growth objective. If company leaders learn the existing projects won’t meet the growth objective, the tidal wave will sweep away some lesser projects to make room for new ones.

There will be great internal pressure to add projects without stopping some, but that won’t work. Everyone is fully booked and can’t deliver on additional projects even if you tell them to. If you’re not willing to stop projects, you’re better off staying the course and waiting until you finish one before you start a project to increase your novelty score.

Novelty is good because there’s more upside potential, and improvement is good because there’s more certainty. One is not better than the other. You need both.

In the end, you’re going to have to judge if you’re happy with what you’ve got. That’s a difficult task that no one can make easier for you. But it is possible to use your judgment better. If you can clearly call out what’s novel and what’s not, you’re on your way.

Image credit – s3aphotography (image cropped)

Hands-On or Hands-Off?

Hands-on versus hands-off – as a leader it’s a fundamental choice. And for me the single most important guiding principle is – do what it takes to maintain or strengthen the team’s personal ownership of the work.

Hands-on versus hands-off – as a leader it’s a fundamental choice. And for me the single most important guiding principle is – do what it takes to maintain or strengthen the team’s personal ownership of the work.

If things are going well, keep your hands off. This reinforces the team’s ownership and your trust in them. But it’s not hands-off in and ignore them sense; it’s hands-off in a don’t tell them what to do sense. Walk around, touch base and check in to show interest in the work and avoid interrogation-based methods that undermine your confidence in them. This is not to say a hands-off leader only superficially knows what’s going on, it should only look like the leader has a superficial understanding.

The hands-off approach requires a deep understanding of the work and the people doing it. The hands-off leader must make the time to know the GPS coordinates of the project and then do reconnaissance work to identify the positions of the quagmires and quicksand that lay ahead. The hands-off leader waits patiently just in front of the obstacles and makes no course correction if the team can successfully navigate the gauntlet. But when the team is about to sink to their waists, leader gently nudges so they skirt the dangerous territory.

Unless, of course, the team needs some learning. And in that case, the leader lets the team march it’s project into the mud. If they need just a bit of learning the leader lets them get a little muddy; and if the team needs deep learning, the leader lets them sink to their necks. Either way, the leader is waiting under cover as they approach the impending snafu and is right beside them to pull them out. But to the team, the hands-off leader is not out in front scouting the new territory. To them, the hands-off leader doesn’t pay all that much attention. To the team, it’s just a coincidence the leader happens to attend the project meeting at a pivotal time and they don’t even recognize when the leader subtly plants the idea that lets the team pull themselves out of the mud.

If after three or four near-drowning incidents the team does not learn or change it’s behavior, it’s time for the hands-off approach to look and feel more hands-on. The leader calls a special meeting where the team presents the status of the project and grounds the project in the now. Then, with everyone on the same page the leader facilitates a process where the next bit of work is defined in excruciating detail. What is the next learning objective? What is the test plan? What will be measured? How will it be measured? How will the data be presented? If the tests go as planned, what will you know? What won’t you know? How will you use the knowledge to inform the next experiments? When will we get together to review the test results and your go-forward recommendations?

By intent, this tightening down does not go unnoticed. The next bit of work is well defined and everyone is clear how and when the work will be completed and when the team will report back with the results. The leader reverts back to hands-off until the band gets back together to review the results where it’s back to hands-on. It’s the leader’s judgement on how many rounds of hands-on roulette the team needs, but the fun continues until the team’s behavior changes or the project ends in success.

For me, leadership is always hands-on, but it’s hands-on that looks like hands-off. This way the team gets the right guidance and maintains ownership. And as long as things are going well this is a good way to go. But sometimes the team needs to know you are right there in the trenches with them, and then it’s time for hands-on to look like hands-on. Either way, its vital the team knows they own the project.

There are no schools that teach this. The only way to learn is to jump in with both feet and take an active role in the most important projects.

Image credit – Kerri Lee Smith

To make the right decision, use the right data.

When it’s time for a tough decision, it’s time to use data. The idea is the data removes biases and opinions so the decision is grounded in the fundamentals. But using the right data the right way takes a lot of disciple and care.

When it’s time for a tough decision, it’s time to use data. The idea is the data removes biases and opinions so the decision is grounded in the fundamentals. But using the right data the right way takes a lot of disciple and care.

The most straightforward decision is a decision between two things – an either or – and here’s how it goes.

The first step is to agree on the test protocols and measure systems used to create the data. To eliminate biases, this is done before any testing. The test protocols are the actual procedural steps to run the tests and are revision controlled documents. The measurement systems are also fully defined. This includes the make and model of the machine/hardware, full definition of the fixtures and supporting equipment, and a measurement protocol (the steps to do the measurements).

The next step is to create the charts and graphs used to present the data. (Again, this is done before any testing.) The simplest and best is the bar chart – with one bar for A and one bar for B. But for all formats, the axes are labeled (including units), the test protocol is referenced (with its document number and revision letter), and the title is created. The title defines the type of test, important shared elements of the tested configurations and important input conditions. The title helps make sure the tested configurations are the same in the ways they should be. And to be doubly sure they’re the same, once the graph is populated with the actual test data, a small image of the tested configurations can be added next to each bar.

The configurations under test change over time, and it’s important to maintain linkage between the test data and the tested configuration. This can be accomplished with descriptive titles and formal revision numbers of the test configurations. When you choose design concept A over concept B but unknowingly use data from the wrong revisions it’s still a data-driven decision, it’s just wrong one.

But the most important problem to guard against is a mismatch between the tested configuration and the configuration used to create the cost estimate. To increase profit, test results want to increase and costs wants to decrease, and this natural pressure can create divergence between the tested and costed configurations. Test results predict how the configuration under test will perform in the field. The cost estimate predicts how much the costed configuration will cost. Though there’s strong desire to have the performance of one configuration and the cost of another, things don’t work that way. When you launch you’ll get the performance of AND cost of the configuration you launched. You might as well choose the configuration to launch using performance data and cost as a matched pair.

All this detail may feel like overkill, but it’s not because the consequences of getting it wrong can decimate profitability. Here’s why:

Profit = (price – cost) x volume.

Test results predict goodness, and goodness defines what the customer will pay (price) and how many they’ll buy (volume). And cost is cost. And when it comes to profit, if you make the right decision with the wrong data, the wheels fall off.

Image credit – alabaster crow photographic

To improve innovation, improve clarity.

If I was CEO of a company that wanted to do innovation, the one thing I’d strive for is clarity.

If I was CEO of a company that wanted to do innovation, the one thing I’d strive for is clarity.

For clarity on the innovative new product, here’s what the CEO needs.

Valuable Customer Outcomes – how the new product will be used. This is done with a one page, hand sketched document that shows the user using the new product in the new way. The tool of choice is a fat black permanent marker on an 81/2 x 11 sheet of paper in landscape orientation. The fat marker prohibits all but essential details and promotes clarity. The new features/functions/finish are sketched with a fat red marker. If it’s red, it’s new; and if you can’t sketch it, you don’t have it. That’s clarity.

The new value proposition – how the product will be sold. The marketing leader creates a one page sales sheet. If it can’t be sold with one page, there’s nothing worth selling. And if it can’t be drawn, there’s nothing there.

Customer classification – who will buy and use the new product. Using a two column table on a single page, these are their attributes to define: Where the customer calls home; their ability to pay; minimum performance threshold; infrastructure gaps; literacy/capability; sustainability concerns; regulatory concerns; culture/tastes.

Market classification – how will it fit in the market. Using a four column table on a single page, define: At Whose Expense (AWE) your success will come; why they’ll be angry; what the customer will throw way, recycle or replace; market classification – market share, grow the market, disrupt a market, create a new market.

For clarity on the creative work, here’s what the CEO needs: For each novel concept generated by the Innovation Burst Event (IBE), a single PowerPoint slide with a picture of its thinking prototype and a word description (limited to 12 words).

For clarity on the problems to be solved the CEO needs a one page, image-based definition of the problem, where the problem is shown to occur between only two elements, where the problem’s spacial location is defined, along with when the problem occurs.

For clarity on the viability of the new technology, the CEO needs to see performance data for the functional prototypes, with each performance parameter expressed as a bar graph on a single page along with a hyperlink to the robustness surrogate (test rig), test protocol, and images of the tested hardware.

For clarity on commercialization, the CEO should see the project in three phases – a front, a middle, and end. The front is defined by a one page project timeline, one page sales sheet, and one page sales goals. The middle is defined by performance data (bar graphs) for the alpha units which are hyperlinked to test protocols and tested hardware. For the end it’s the same as the middle, except for beta units, and includes process capability data and capacity readiness.

It’s not easy to put things on one page, but when it’s done well clarity skyrockets. And with improved clarity the right concepts are created, the right problems are solved, the right data is generated, and the right new product is launched.

And when clarity extends all the way to the CEO, resources are aligned, organizational confusion dissipates, and all elements of innovation work happen more smoothly.

Image credit – Kristina Alexanderson

Prototypes Are The Best Way To Innovate

If you’re serious about innovation, you must learn, as second nature, to convert your ideas into prototypes.

If you’re serious about innovation, you must learn, as second nature, to convert your ideas into prototypes.

Funny thing about ideas is they’re never fully formed – they morph and twist as you talk about them, and as long as you keep talking they keep changing. Evolution of your ideas is good, but in the conversation domain they never get defined well enough (down to the nuts-and-bolts level) for others (and you) to know what you’re really talking about. Converting your ideas into prototypes puts an end to all the nonsense.

Job 1 of the prototype is to help you flesh out your idea – to help you understand what it’s all about. Using whatever you have on hand, create a physical embodiment of your idea. The idea is to build until you can’t, to build until you identify a question you can’t answer. Then, with learning objective in hand, go figure out what you need to know, and then resume building. If you get to a place where your prototype fully captures the essence of your idea, it’s time to move to Job 2. To be clear, the prototype’s job is to communicate the idea – it’s symbolic of your idea – and it’s definitely not a fully functional prototype.

Job 2 of the prototype is to help others understand your idea. There’s a simple constraint in this phase – you cannot use words – you cannot speak – to describe your prototype. It must speak for itself. You can respond to questions, but that’s it. So with your rough and tumble prototype in hand, set up a meeting and simply plop the prototype in front of your critics (coworkers) and watch and listen. With your hand over your mouth, watch for how they interact with the prototype and listen to their questions. They won’t interact with it the way you expect, so learn from that. And, write down their questions and answer them if you can. Their questions help you see your idea from different perspectives, to see it more completely. And for the questions you cannot answer, they the next set of learning objectives. Go away, learn and modify your prototype accordingly (or build a different one altogether). Repeat the learning loop until the group has a common understanding of the idea and a list of questions that only a customer can answer.

Job 3 is to help customers understand your idea. At this stage it’s best if the prototype is at least partially functional, but it’s okay if it “represents” the idea in clear way. The requirement is prototype is complete enough for the customer can form an opinion. Job 3 is a lot like Job 2, except replace coworker with customer. Same constraint – no verbal explanation of the prototype, but you can certainly answer their direction questions (usually best answered with a clarifying question of your own such as “Why do you ask?”) Capture how they interact with the prototype and their questions (video is the best here). Take the data back to headquarters, and decide if you want to build 100 more prototypes to get a broader set of opinions; build 1000 more and do a small regional launch; or scrap it.

Building a prototype is the fastest, most effective way to communicate an idea. And it’s the best way to learn. The act of building forces you to make dozens of small decisions to questions you didn’t know you had to answer and the physical nature the prototype gives a three dimensional expression of the idea. There may be disagreement on the value of the idea the prototype stands for, but there will be no ambiguity about the idea.

If you’re not building prototypes early and often, you’re not doing innovation. It’s that simple.

How Things Really Happen

From the outside it’s unclear how things happen; but from the inside it’s clear as day. No, it’s not your bulletproof processes; it’s not your top down strategy; and it’s not your operating plans. It’s your people.

At some level everything happens like this:

An idea comes to you that makes little sense, so you drop it. But it comes again, and then again. It visits regularly over the months and each time reveals a bit of its true self. But still, it’s incomplete. So you walk around with it and it eats at you; like a parasite, it gets stronger at your expense. Then, it matures and grows its voice – and it talks to you. It talks all the time; it won’t let you sleep; it pollutes you; it gets in the way; it colors you; and finally you become the human embodiment of the idea.

And then it tips you. With one last push, it creates enough discomfort to roll over the fear of acknowledging its existence, and you set up the meeting.

You call the band and let them know it’s time again to tour. You’ve been through it before and you all know deal. You know your instruments and you know how to harmonize. You know what they can do (because they’ve done it before) and you trust them. You sing them the song of your idea and they listen. Then you ask them to improvise and sing it back, and you listen. The mutual listening moves the idea forward, and you agree to take a run at it.

You ask how it should go. The lead vocalist tells you how it should be sung; the lead guitar works out the fingering; the drummer beats out the rhythm; and the keyboardist grins and says this will be fun. You all know the sheet music and you head back to your silos to make it happen.

In record time, the work gets done and you get back together to review the results. As a group you decide if the track is good enough play in public. If it is, you set up the meeting with a broader audience to let them hear your new music. If it’s not, you head back to the recording studio to amplify what worked and dampen what didn’t. You keep re-recording until your symphony is ready for the critics.

Things happen because artists who want to make a difference band together and make a difference. With no complicated Gantt chart, no master plan, no request for approval, and no additional resources, they make beautiful music where there had been none. As if from thin air, they create something from nothing. But it’s not from thin air; it’s from passion, dedication, trust, and mutual respect.

The business books over-complicate it. Things happen because people make them happen – it’s that simple.

The Threshold Of Uncertainty

Our threshold for uncertainty is too low.

Our threshold for uncertainty is too low.

Early in projects, even before the first prototype is up and running, you know what the product must do, what it will cost, and, most problematic, when you’ll be done. Independent of work content, level of newness, and workloads, there’s no uncertainty in your launch date. It’s etched in stone and the consequences are devastating.

A zero tolerance policy on uncertainty forces irrational behavior. As soon as possible, engineering gets something running in the lab, and then doesn’t want to change it because there’s no time. The prototype is almost impossible to build and is hypersensitive to normal process variation, but these issues are not addressed because there’s no time. Everyone agrees it’s important to fix it, and agrees to fix it after launch, but that never happens because the next project is already late before it starts. And the death cycle repeats project after project.

The root cause of this mess is the mistaken porting of manufacturing’s zero uncertainly mindset into design. The thinking goes like this – lean and Six Sigma have achieved magical success in manufacturing by eliminating uncertainty, so let’s do it in product design and achieve similar results. This is a fundamental mistake as the domains are fundamentally different.

In manufacturing the same product is made day-in and day-out – no uncertainty; in product design no two product development efforts are the same and there’s lots of stuff that’s done for the first time – uncertainty by definition. In manufacturing there’s a revision controlled engineering drawing that defines the right answer (the geometry and the material) – make it like the picture and it’s all good; in product design the material is chosen from many candidates and the geometry is created from scratch – the picture is created from nothing. By definition there’s more inherent uncertainty in product design, and to tighten the screws and fix the launch date at the start is inappropriate.

Design engineers must feel like there’s enough time to try new things because new products that provide new functionality require new technologies, new materials, and new geometries. With new comes inherent uncertainty, but there are ways to manage it.

To hold the timeline, give on the specification and cost. Design as fast as you can until you run out of time then launch. The product won’t work as well as you’d like and it will cost more than you’d like, but you’ll hit the schedule. A good way to do this is to de-feature a subassembly to reduce design time, and possibly reduce cost. Or, reuse a proven subassembly to reduce design time – take a hit in cost, but hit the timeline. The general idea – hold schedule but flex on performance and cost.

It feels like sacrilege to admit that something’s got to give, but it’s the truth. You’ve seen how it goes when you edict (in no uncertain terms) that the timeline will be met and there’ll be no give on performance and cost. It hasn’t worked, and it won’t – the inherent uncertainty of product design won’t let it.

Accept the uncertainty; be one with it; and manage it. It’s the only way.

Incomplete Definition – A Way Of Life

At the start of projects, no one knows what to do. Engineering complains the specification isn’t fully defined so they cannot start, and marketing returns fire with their complaint – they don’t yet fully understand the customer needs, can’t lock down the product requirements, and need more time. Marketing wants to keep things flexible and engineering wants to lock things down; and the result is a lot of thrashing and flailing and not nearly enough starting.

At the start of projects, no one knows what to do. Engineering complains the specification isn’t fully defined so they cannot start, and marketing returns fire with their complaint – they don’t yet fully understand the customer needs, can’t lock down the product requirements, and need more time. Marketing wants to keep things flexible and engineering wants to lock things down; and the result is a lot of thrashing and flailing and not nearly enough starting.

Both camps are right – the spec is only partially formed and customer needs are only partially understood – but the project must start anyway. But the situation isn’t as bad as it seems. At the start of a project fully wrung out specs and fully validated customer needs aren’t needed. What’s needed is definition of product attributes that set its character, definition of how those attributes will be measured, and definition of the competitive products. The actual values of the performance attributes aren’t needed, just their name, their relative magnitude expressed as percent improvement, and how they’ll be measured.

And to do this the project manager asks the engineering and marketing groups to work together to create simple bar charts for the most important product attributes and then schedules the meeting where the group jointly presents their single set of bar charts.

This little trick is more powerful than it seems. In order to choose competitive products, a high level characterization of the product must be roughed out; and once chosen they paint a picture of the landscape and set the context for the new product. And in order to choose the most important performance (or design) attributes, there must be convergence on why customers will buy it; and once chosen they set the context for the required design work.

Here’s an example. Audi wants to start developing a new car. The marketing-engineering team is tasked to identify the competitive products. If the competitive products are BMW 7 series, Mercedes S class, and the new monster Hyundai, the character of the new car and the character of the project are pretty clear. If the competitive products are Ford Focus, Fiat F500, and Mini Cooper, that’s a different project altogether. For both projects the team doesn’t know every specification, but it knows enough to start. And once the competitive products are defined, the key performance attributes can be selected rather easily.

But the last part is the hardest – to define how the performance characteristics will be measured, right down to the test protocols and test equipment. For the new Audi fuel economy will be measured using both the European and North American drive cycles and measured in liters per 100 kilometer and miles per gallon (using a pre-defined fuel with an 89 octane rating); interior noise will be measured in six defined locations using sound meter XYZ and expressed in decibels; and overall performance will be measured by the lap time around the Nuremburg Ring under full daylight, dry conditions, and 25 Centigrade ambient temperature, measured in minutes.

Bar charts are created with the names of the competitive vehicles (and the new Audi) below each bar and performance attribute (and units, e.g., miles per gallon) on the right. Side-by-side, it’s pretty clear how the new car must perform. Though the exact number is not know, there’s enough to get started.

At the start of a project the objective is to make sure you’re focusing on the most performance attributes and to create clarity on how the attributes (and therefore the product) will be measured. There’s nothing worse than spending engineering resources in the wrong area. And it’s doubly bad if your misplaced efforts actually create constraints that limit or reduce performance of the most important attributes. And that’s what’s to be avoided.

As the project progresses, marketing converges on a detailed understanding of customer needs, and engineering converges on a complete set of specifications. But at the start, everything is incomplete and no part of the project is completely nailed down.

The trick is to define the most important things as clearly as possible, and start.

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski