Posts Tagged ‘Problem Definition’

Without a problem there can be no progress.

Without a problem, there can be no progress.

And only after there’s too much no progress is a problem is created.

And once the problem is created, there can be progress.

When you know there’s a problem just over the horizon, you have a problem.

Your problem is that no one else sees the future problem, so they don’t have a problem.

And because they have no problem, there can be no progress.

Progress starts only after the calendar catches up to the problem.

When someone doesn’t think they have a problem, they have two problems.

Their first problem is the one they don’t see, and their second is that they don’t see it.

But before they can solve the first problem, they must solve the second.

And that’s usually a problem.

When someone hands you their problem, that’s a problem.

But if you don’t accept it, it’s still their problem.

And that’s a problem, for them.

When you try to solve every problem, that’s a problem.

Some problems aren’t worth solving.

And some don’t need to be solved yet.

And some solve themselves.

And some were never really problems at all.

When you don’t understand your problem, you have two problems.

Your first is the problem you have and your second is that you don’t know what your problem by name.

And you’ve got to solve the second before the first, which can be a problem.

With a big problem comes big attention. And that’s a problem.

With big attention comes a strong desire to demonstrate rapid progress. And that’s a problem.

And because progress comes slowly, fervent activity starts immediately. And that’s a problem.

And because there’s no time to waste, there’s no time to define the right problems to solve.

And there’s no bigger problem than solving the wrong problems.

No Time for the Truth

Company leaders deserve to know the truth, but they can no longer take the time to learn it.

Company leaders deserve to know the truth, but they can no longer take the time to learn it.

Company leaders are pushed too hard to grow the business and can no longer take the time to listen to all perspectives, no longer take the time to process those perspectives, and no longer take the time to make nuanced decisions. Simply put, company leaders are under too much pressure to grow the business. It’s unhealthy pressure and it’s too severe. And it’s not good for the company or the people that work there.

What’s best for the company is to take the time to learn the truth.

Getting to the truth moves things forward. Sure, you may not see things correctly, but when you say it like you see it, everyone’s understanding gets closer to the truth. And when you do see things clearly and correctly, saying what you see moves the company’s work in a more profitable direction. There’s nothing worse than spending time and money to do the work only to learn what someone already knew.

What’s best for the company is to tell the truth as you see it.

All of us have good intentions but all of us are doing at least two jobs. And it’s especially difficult for company leaders, whose responsibility is to develop the broadest perspective. Trouble is, to develop that broad perspective sometime comes at the expense of digging into the details. Perfectly understandable, as that’s the nature of their work. But subject matter experts (SMEs) must take the time to dig into the details because that’s the nature of their work. SMEs have an obligation to think things through, communicate clearly, and stick to their guns. When asked broad questions, good SMEs go down to bedrock and give detailed answers. And when asked hypotheticals, good SMEs don’t speculate outside their domain of confidence. And when asked why-didn’t-you’s, good SMEs answer with what they did and why they did it.

Regardless of the question, the best SMEs always tell the truth.

SMEs know when the project is behind. And they know the answer that everyone thinks will get the project get back on schedule. And the know the truth as they see it. And when there’s a mismatch between the answer that might get the project back on schedule and the truth as they see it, they must say it like they see it. Yes, it costs a lot of money when the project is delayed, but telling the truth is the fastest route to commercialization. In the short term, it’s easier to give the answer that everyone thinks will get things back on track. But truth is, it’s not faster because the truth comes out in the end. You can’t defy the physics and you can’t transcend the fundamentals. You must respect the truth. The Universe doesn’t care if the truth is inconvenient. In the end, the Universe makes sure the truth carries the day.

We’re all busy. And we all have jobs to do. But it’s always the best to take the time to understand the details, respect the physics, and stay true to the fundamentals.

When there’s a tough decision, understand the fundamentals and the decision will find you.

When there’s disagreement, take the time to understand the physics, even the organizational kind. And the right decision will meet you where you are.

When the road gets rocky, ask your best SMEs what to do, and do that.

When it comes to making good decisions, sometimes slower is faster.

Image credit — Dennis Jarvis

Want to succeed? Learn how to deliver customer value.

Whatever your initiative, start with customer value. Whatever your project, base it on customer value. And whatever your new technology, you guessed it, customer value should be front and center.

Whatever your initiative, start with customer value. Whatever your project, base it on customer value. And whatever your new technology, you guessed it, customer value should be front and center.

Whenever the discussion turns to customer value, expect confusion, disagreement, and, likely, anger. To help things move forward, here’s an operational definition I’ve found helpful:

When they buy it for more than your cost to make it, you have customer value.

And when there’s no way to pull out of the death spiral of disagreement, use this operational definition to avoid (or stop) bad projects:

When no one will buy it, you don’t have customer value and it’s a bad project.

As two words, customer and value don’t seem all that special. But, when you put them together, they become words to live by. But, also, when you do put them together, things get complicated. Here’s why.

To provide customer value, you’ve got to know (and name) the customer. When you asked “Who is the customer?” the wheels fall off. Here are some wrong answers to that tricky question. The Board of Directors is the customer. The shareholders are the customers. The distributor is the customer. The OEM that integrates your product is the customer. And the people that use the product are the customer. Here’s an operational definition that will set you free:

When someone buys it, they are the customer.

When the discussions get sticky, hold onto that definition. Others will try to bait you into thinking differently, but don’t bite. It will be difficult to stand your ground. And if you feel the group is headed in the wrong direction, try to set things right with this operational definition:

When you’ve found the person who opens their wallet, you’ve found the customer.

Now, let’s talk about value. Isn’t value subjective? Yes, it is. And the only opinion that matters is the customer’s. And here’s an operational definition to help you create customer value:

When you solve an important customer problem, they find it valuable.

And there you have it. Putting it all together, here’s the recipe for customer value:

- Understand who will buy it.

- Understand their work and identify their biggest problem.

- Solve their problem and embed it in your offering.

- Sell it for more than it costs you to make it.

Image credit — Caroline

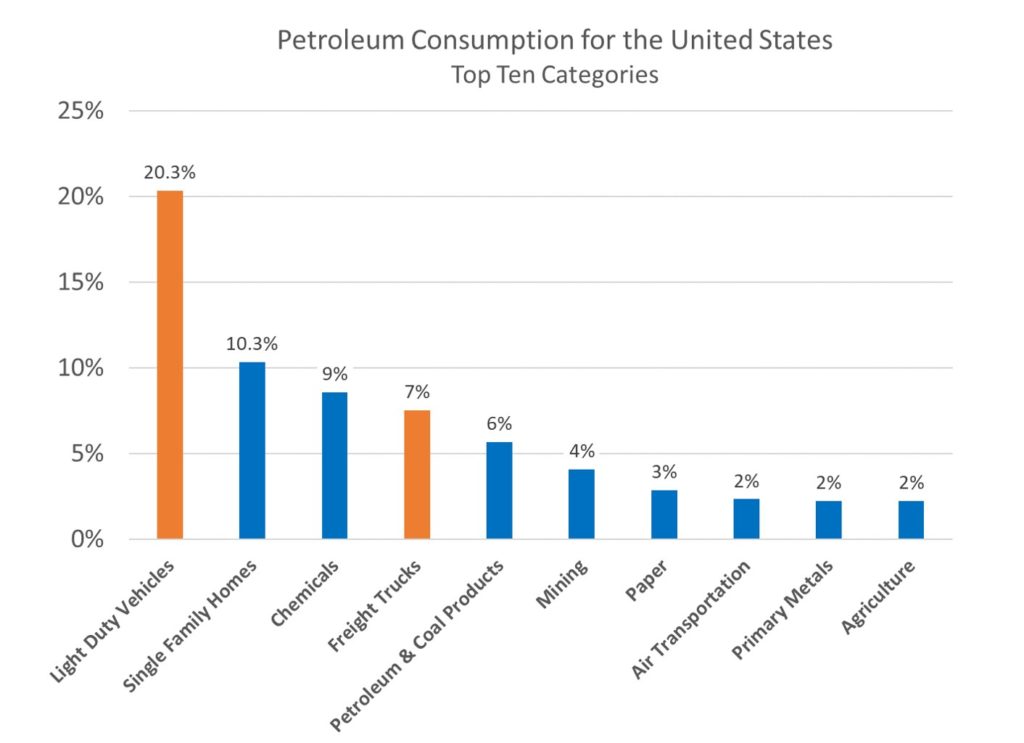

Where is petroleum consumed?

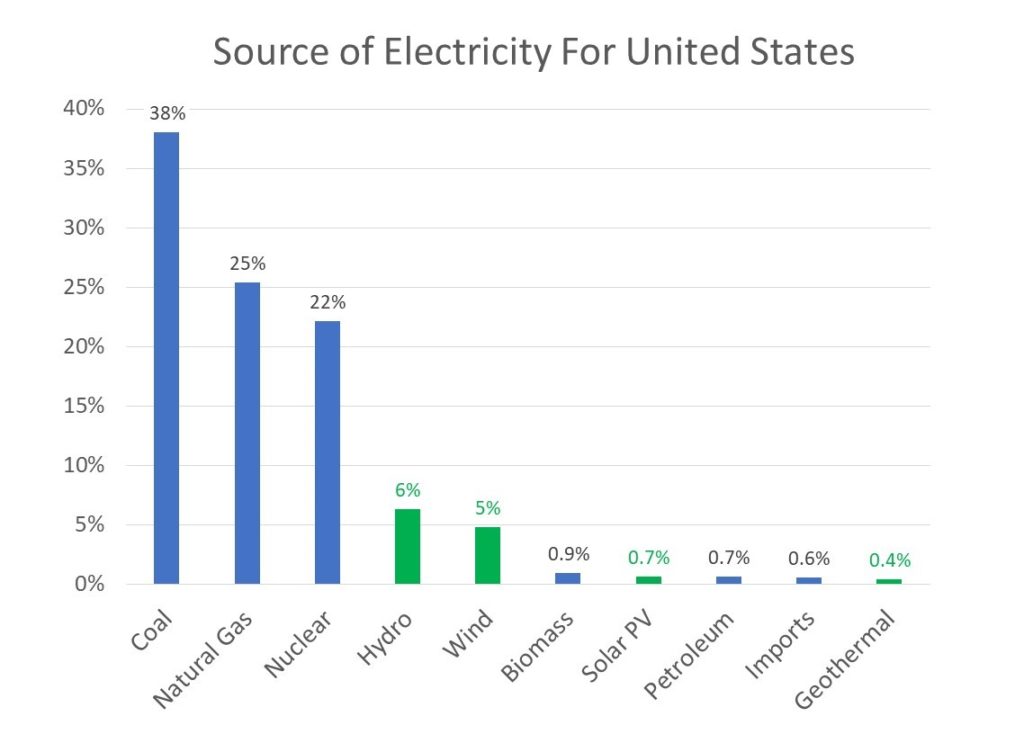

In last week’s post, I provided a chart that describes the sources of electricity for the United States. Coal is the largest source of electricity (38%) and natural gas is the next largest (25%). The largest non-carbon source is nuclear (22%) and the largest renewable sources are wind (6%) and solar (5%). The data from the chart came from Otherlab who was contracted by the Advanced Research Project Agency of the Department of Energy (ARPA-e) to review all available energy data sources and create an ultra-high resolution picture of the U.S. energy economy.

In last week’s post, I provided a chart that describes the sources of electricity for the United States. Coal is the largest source of electricity (38%) and natural gas is the next largest (25%). The largest non-carbon source is nuclear (22%) and the largest renewable sources are wind (6%) and solar (5%). The data from the chart came from Otherlab who was contracted by the Advanced Research Project Agency of the Department of Energy (ARPA-e) to review all available energy data sources and create an ultra-high resolution picture of the U.S. energy economy.

Using the same data set, I created a chart to break out the top ten categories for petroleum consumption for the United States.

The category Light-Duty Vehicles (cars, light trucks) is the largest consumer at 20% and is more than the sum of the next two categories – Single-Family Homes (10%) and Chemicals (9%).

When Light-Duty Vehicles at 20% are combined with Freight Trucks (think eighteen-wheelers) at 7%, they make up 27% of the country’s total consumption, making the Transportation sector the thirstiest. The most effective way to reduce petroleum consumption is to replace vehicles powered by internal combustion engines with electric vehicles (EVs). But there’s a catch.

As internal combustion engines diminish and EVs come online, petroleum consumption will drop and will help the planet. But, as EVs come online the demand for electricity will increase, making it even more important to replace coal and natural gas with zero-carbon sources of electricity: nuclear, hydro, wind and solar.

To save the planet, here’s what you can do. Vote for political candidates who will end federal subsidies for coal and natural gas. That single change will accelerate the adoption of wind and solar, as it will increase the existing cost advantage of wind and solar. And if that freed-up money can be reallocated to federally-funded R&D to improve the controllability of electrical grids, the change will come even sooner.

And at the state and local level, you can vote for candidates that want to make it easier for wind and solar projects to be funded.

And, lastly, you can buy an EV. You will see a much larger selection of new electric vehicles over the next year and the driving range continues to improve. Over the next year, most new EV models will be high performance and high cost, lower-cost EVs should follow soon after.

Image credit – NASA Goodard Flight Center

How is your electricity made?

How is your electricity made? Which source produces the most electricity? How much is made from zero-carbon sources? How much is made from renewable sources?

How is your electricity made? Which source produces the most electricity? How much is made from zero-carbon sources? How much is made from renewable sources?

In 2017, Otherlab was contracted by the Advanced Research Project Agency of the Department of Energy (ARPA-e) to review all available energy data sources and create an ultra-high resolution picture of the U.S. energy economy. The purpose was to identify research priorities and to model scenarios for new energy technologies and policies. This work leveraged many decades of effort by the U.S. Energy Information Agency (PDF) and Lawrence Livermore National Lab analyzing the U.S. energy economy and providing annual snapshots in a Sankey Flow Diagram format. The Otherlab “Super Sankey” tool is available at www.departmentof.energy

Here’s a link to Otherlab’s original post on the project.

The Sankey Flow diagram format can be difficult at first, so I created a simple chart to break down the electricity sources for the United States.

As you can see, we have a long way to go to replace coal and natural gas, the two most troublesome sources for the planet. Together, coal and gas are responsible for 63% of the country’s electricity. The next largest source is nuclear at 22%. Nuclear is a carbon-free source of electricity, but it’s not renewable and it produces waste that must be stored for a long time in secure vaults. Nuclear is often considered a good solution to produce carbon-free electricity (at least while renewable sources come online), but it’s a politically charged technology due to the perceived danger of catastrophic failure of nuclear powerplants.

The largest renewable source of electricity is hydro at 6% and wind is next at 5%. We hear a lot about solar, but it produces a small fraction of our electricity. And we don’t hear much about geothermal which is about half the size of solar.

These numbers may differ a bit from those calculated from other data sources, but the picture is clear. We’ve got a long way to go to displace coal and natural gas. But the cost of renewable sources is now less than coal and natural gas. You’ll soon see more coal plants closing and reduced sales of natural gas power turbine generators.

If we are to do one thing to accelerate the transition to renewable sources of electricity, we should end subsidies paid to coal and natural gas industries and use the freed-up money to create the next-generation technologies that help the grid accept more renewable sources of electricity.

Image credit – Andreas Øverland

Innovation isn’t uncertain, it’s unknowable.

Where’s the Marketing Brief? In product development, the Marketing team creates a document that defines who will buy the new product (the customer), what needs are satisfied by the new product and how the customer will use the new product. And Marketing team also uses their crystal ball to estimate the number of units the customers will buy, when they’ll buy it and how much they’ll pay. In theory, the Marketing Brief is finalized before the engineers start their work.

Where’s the Marketing Brief? In product development, the Marketing team creates a document that defines who will buy the new product (the customer), what needs are satisfied by the new product and how the customer will use the new product. And Marketing team also uses their crystal ball to estimate the number of units the customers will buy, when they’ll buy it and how much they’ll pay. In theory, the Marketing Brief is finalized before the engineers start their work.

With innovation, there can be no Marketing Brief because there are no customers, no product and no technology to underpin it. And the needs the innovation will satisfy are unknowable because customers have not asked for the them, nor can the customer understand the innovation if you showed it to them. And how the customers will use the? That’s unknowable because, again, there are no customers and no customer needs. And how many will you sell and the sales price? Again, unknowable.

Where’s the Specification? In product development, the Marketing Brief is translated into a Specification that defines what the product must do and how much it will cost. To define what the product must do, the Specification defines a set of test protocols and their measurable results. And the minimum performance is defined as a percentage improvement over the test results of the existing product.

With innovation, there can be no Specification because there are no customers, no product, no technology and no business model. In that way, there can be no known test protocols and the minimum performance criteria are unknowable.

Where’s the Schedule? In product development, the tasks are defined, their sequence is defined and their completion dates are defined. Because the work has been done before, the schedule is a lot like the last one. Everyone knows the drill because they’ve done it before.

With innovation, there can be no schedule. The first task can be defined, but the second cannot because the second depends on the outcome of the first. If the first experiment is successful, the second step builds on the first. But if the first experiment is unsuccessful, the second must start from scratch. And if the customer likes the first prototype, the next step is clear. But if they don’t, it’s back to the drawing board. And the experiments feed the customer learning and the customer learning shapes the experiments.

Innovation is different than product development. And success in product development may work against you in innovation. If you’re doing innovation and you find yourself trying to lock things down, you may be misapplying your product development expertise. If you’re doing innovation and you find yourself trying to write a specification, you may be misapplying your product development expertise. And if you are doing innovation and find yourself trying to nail down a completion date, you are definitely misapplying your product development expertise.

With innovation, people say the work is uncertain, but to me that’s not the right word. To me, the work is unknowable. The customer is unknowable because the work hasn’t been done before. The specification is unknowable because there is nothing for comparison. And the schedule in unknowable because, again, the work hasn’t been done before.

To set expectations appropriately, say the innovation work is unknowable. You’ll likely get into a heated discuss with those who want demand a Marketing Brief, Specification and Schedule, but you’ll make the point that with innovation, the rules of product development don’t apply.

Image credit — Fatih Tuluk

Advice To Young Design Engineers

If your solution isn’t sold to a customer, you didn’t do your job. Find a friend in Marketing.

If your solution can’t be made by Manufacturing, you didn’t do your job. Find a friend in Manufacturing.

Reuse all you can, then be bold about trying one or two new things.

Broaden your horizons.

Before solving a problem, make sure you’re solving the right one.

Don’t add complexity. Instead, make it easy for your customers.

Learn the difference between renewable and non-renewable resources and learn how to design with the renewable ones.

Learn how to do a Life Cycle Assessment.

Learn to see functional coupling and design it out.

Be afraid but embrace uncertainty.

Learn how to communicate your ideas in simple ways. Jargon is a sign of weakness.

Before you can make sure you’re solving the right problem, you’ve got to know what problem you’re trying to solve.

Learn quickly by defining the tightest learning objective.

Don’t seek credit, seek solutions. Thrive, don’t strive.

Be afraid, and run toward the toughest problems.

Help people. That’s your job.

Image credit – Marco Verch

What’s your problem?

If you don’t have a problem, you’ve got a big problem.

If you don’t have a problem, you’ve got a big problem.

It’s important to know where a problem happens, but also when it happens.

Solutions are 90% defining and the other half is solving.

To solve a problem, you’ve got to understand things as they are.

Before you start solving a new problem, solve the one you have now.

It’s good to solve your problems, but it’s better to solve you customers’ problems.

Opportunities are problems in sheep’s clothing.

There’s nothing worse than solving the wrong problem – all the cost with none of the solution.

When you’re stumped by a problem, make it worse then do the opposite.

With problem definition, error on the side of clarity.

All problems are business problems, unless you care about society’s problems.

Odds are, your problem has been solved by someone else. Your real problem is to find them.

Define your problem as narrowly as possible, but no narrower.

Problems are not a sign of weakness.

Before adding something to solve the problem, try removing something.

If your problem involves more than two things, you have more than one problem.

The problem you think you have is never the problem you actually have.

Problems can be solved before, during or after they happen and the solutions are different.

Start with the biggest problem, otherwise you’re only getting ready to solve the biggest problem.

If you can’t draw a closeup sketch of the problem, you don’t understand it well enough.

If you have an itchy backside and you scratch you head, you still have an itch. And it’s the same with problems.

If innovation is all about problem solving and problem solving is all about problem definition, well, there you have it.

Image credit – peasap

Too Many Balls in the Air

In today’s world of continuous improvement, everything is seen as an opportunity for improvement. The good news is things are improving. But the bad news is without governance and good judgement, things can flip from “lots of opportunity for improvement” to “nothing is good enough.” And when that happens people would rather hang their heads than stick out their necks.

In today’s world of continuous improvement, everything is seen as an opportunity for improvement. The good news is things are improving. But the bad news is without governance and good judgement, things can flip from “lots of opportunity for improvement” to “nothing is good enough.” And when that happens people would rather hang their heads than stick out their necks.

When there’s an improvement goal is propose like this “We’ve got to improve the throughput of process A by 12% over the next three months.” a company that respects their people should want (and expect) responses like these:

As you know, the team is already working to improve processes C, D, and E and we’re behind on those improvement projects. Is improvement of process A more important than the other three? If so, which project do you want to stop so we can start work on process A? If not, can we wait until we finish one of the existing projects before we start a new one? If not, why are you overloading us when we’re making it clear we already have too much work?

Are we missing customer ship dates on process A? If so, shouldn’t we move resources to process A right now to work off the backlog? If we have no extra resources, let’s authorize some overtime so we can catch up. If not, why is it okay to tolerate late shipments to our customers? Are you saying you want us to do more improvement work AND increase production without overtime?

That’s a pretty specific improvement goal. What are the top three root causes for reduced throughput? Well, if the first part of the improvement is to define the root causes, how do you know we can achieve 12% improvement in 3 months? We learned in our training that Deming said all targets are artificial. Are you trying to impose an artificial improvement target and set us up for failure?

Continuous improvement is infinitely good, but resources are finite. Like it or not, continuous improvement work WILL be bound by the resources on hand. Might as well ask for continuous improvement work in a way that’s in line with the reality of the team’s capacity.

And one thing to remember for all projects – there’s no partial credit. When you’re 80% done on ten projects, zero projects are done. It’s infinitely better to be 100% done on a single project.

Image credit – Gabriel Rojas Hruska

If you want to learn, define a learning objective.

Innovation is all about learning. And if the objective of innovation is learning, why not start with learning objectives?

Innovation is all about learning. And if the objective of innovation is learning, why not start with learning objectives?

Here’s a recipe for learning: define what you want to learn, figure how you want to learn, define what you’ll measure, work the learning plan, define what you learned and repeat.

With innovation, the learning is usually around what customers/users want, what new things (or processes) must be created to satisfy their needs and how to deliver the useful novelty to them. Seems pretty straightforward, until you realize the three elements interact vigorously. Customers’ wants change after you show them the new things you created. The constraints around how you can deliver the useful novelty (new product or service) limit the novelty you can create. And if the customers don’t like the novelty you can create, well, don’t bother delivering it because they won’t buy it.

And that’s why it’s almost impossible to develop a formal innovation process with a firm sequence of operations. Turns out, in reality the actual process looks more like a fur ball than a flow chart. With incomplete knowledge of the customer, you’ve got to define the target customer, knowing full-well you don’t have it right. And at the same time, and, again, with incomplete knowledge, you’ve got to assume you understand their problems and figure out how to solve them. And at the same time, you’ve got to understand the limitations of the commercialization engine and decide which parts can be reused and which parts must be blown up and replaced with something new. All three explore their domains like the proverbial drunken sailor, bumping into lampposts, tripping over curbs and stumbling over each other. And with each iteration, they become less drunk.

If you create an innovation process that defines all the if-then statements, it’s too complicated to be useful. And, because the if-thens are rearward-looking, they don’t apply the current project because every innovation project is different. (If it’s the same as last time, it’s not innovation.) And if you step up the ladder of abstraction and write the process at a high level, the process steps are vague, poorly-defined and less than useful. What’s a drunken sailor to do?

Define the learning objectives, define the learning plan, define what you’ll measure, execute the learning plan, define what you learned and repeat.

When the objective is learning, start with the learning objectives.

Image credit Jean L.

Don’t trust your gut, run the test.

At first glance, it seems easy to run a good test, but nothing can be further from the truth.

At first glance, it seems easy to run a good test, but nothing can be further from the truth.

The first step is to define the idea/concept you want to validate or invalidate. The best way is to complete one of these two sentences: I want to learn that [type your idea here] is true. Or, I want to learn that [enter your idea here] is false.

Next, ask yourself this question: What information do I need to validate (or invalidate) [type your idea here]? Write down the information you need. In the engineering domain, this is straightforward: I need the temperature of this, the pressure of that, the force generated on part xyz or the time (in seconds) before the system catches fire. But for people-related ideas, things aren’t so straightforward. Some things you may want to know are: how much will you pay for this new thing, how many will you buy, on a scale of 1 to 5 how much do you like it?

Now the tough part – how will you judge pass or fail? What is the maximum acceptable temperature? What is the minimum pressure? What is the maximum force that can be tolerated? How many seconds must the system survive before catching fire? And for people: What is the minimum price that can support a viable business? How many must they buy before the company can prosper? And if they like it at level 3, it’s a go. And here’s the most importance sentence of the entire post:

The decision criteria must be defined BEFORE running the test.

If you wait to define the go/no-go criteria until after you run the test and review the data, you’ll adjust the decision criteria so you make the decision you wanted to make before running the test. If you’re not going to define the decision criteria before running the test, don’t bother running the test and follow your gut. Your decision will be a bad one, but at least you’ll save the time and money associated with the test.

And before running the test, define the test protocol. Think recipe in a cookbook: a pinch of this, a quart of that, mix it together and bake at 350 degrees Fahrenheit for 40 minutes. The best protocols are simple and clear and result in the same sequence of events regardless of who runs the test. And make sure the measurement method is part of the protocol – use this thermocouple, use that pressure gauge, use the script to ask the questions about price and the number they’d buy.

And even with all this rigor, good judgement is still part of the equation. But the judgment is limited to questions like: did we follow the protocol? Did the measurement system function properly? Do the initial assumptions still hold? Did anything change since we defined the learning objective and defined the test protocol?

To create formal learning objectives, to write well-defined test protocols and to formalize the decision criteria before running the test require rigor, discipline, time and money. But, because the cost of making a bad decision is so high, the cost of running good tests is a bargain at twice the price.

Image credit – NASA Goddard Flight Center

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski