Posts Tagged ‘Engineering Mindset’

It’s all about judgement.

It’s high tide for innovation – innovate, innovate, innovate. Do it now; bring together the experts; hold an off-site brainstorm session; generate 106 ideas. Fast and easy; anyone can do that. Now the hard part: choose the projects to work on. Say no to most and yes to a few. Choose and execute.

It’s high tide for innovation – innovate, innovate, innovate. Do it now; bring together the experts; hold an off-site brainstorm session; generate 106 ideas. Fast and easy; anyone can do that. Now the hard part: choose the projects to work on. Say no to most and yes to a few. Choose and execute.

To choose we use processes to rank and prioritize; we assign scores 1-5 on multiple dimensions and multiply. Highest is best, pull the trigger, and go. Right? (Only if it was that easy.) Not how it goes.

After the first round of scoring we hold a never-ending series of debates over the rankings; we replace 5s with 3s and re-run the numbers; we replace 1s with 5s and re-re-run. We crank on Excel like the numbers are real, like 5 is really 5. Face it – the scores are arbitrary, dimensionless numbers, quasi-variables data based on judgment. Face it – we manipulate the numbers until the prioritization fits our judgment.

Clearly this is a game of judgment. There’s no data for new products, new technologies, and new markets (because they don’t exist), and the data you have doesn’t fit. (That’s why they call it new.) No market – the objective is to create it; no technology – same objective, yet we cloak our judgment in self-invented, quasi-variables data, and the masquerade doesn’t feel good. It would be a whole lot better if we openly acknowledged it’s judgment-based – smoother, faster, and more fun.

Instead of the 1-3-5 shuffle, try a story-based approach. Place the idea in the context of past, present, and future; tell a tale of evolution: the market used to be like this with a fundamental of that; it moved this way because of the other, I think. By natural extension (or better yet, unnatural), my judgment is the new market could be like this… (If you say will, that’s closeted 1-3-5 behavior.) While it’s the most probable market in my judgment, there is range of possible markets…

Tell a story through analogy: a similar technology started this way, which was based on a fundamental of that, and evolved to something like the other. By natural evolution (use TRIZ) my technical judgment is the technology could follow a similar line of evolution like this…. However, there are a range of possible evolutionary directions that it could follow, kind of like this or that.

And what’s the market size? As you know, we don’t sell any now. (No kidding we don’t sell any, we haven’t created the technology and the market does not exist. That’s what the project is about.) Some better questions: what could the market be? Judgment required. What could the technology be? Judgment. If the technology works, is the market sitting there under the dirt just waiting to be discovered? Judgment.

Like the archeologist, we must translate the hieroglyphs, analyze the old maps, and interpret the dead scrolls. We must use our instinct, experience, and judgment to choose where to dig.

Like it or not, it’s a judgment game, so make your best judgment, and dig like hell.

Improve the US economy, one company at a time.

I think we can turn around the US economy, one company at a time. Here’s how:

I think we can turn around the US economy, one company at a time. Here’s how:

To start, we must make a couple commitments to ourselves. 1. We will do what it takes to manufacture products in the US because it’s right for the country. 2. We will be more profitable because of it.

Next, we will set up a meeting with our engineering community, and we will tell them about the two commitments. (We will wear earplugs because the cheering will be overwhelming.) Then, we will throw down the gauntlet; we will tell them that, going forward, it’s no longer acceptable to design products as before, that going forward the mantra is: half the cost, half the parts, half the time. Then we will describe the plan.

On the next new product we will define cost, part count, and assembly time goals 50% less that the existing product; we will train the team on DFMA; we will tear apart the existing product and use the toolset; we will learn where the cost is (so we can design it out); we will learn where the parts are (so we can design them out); we will learn where the assembly time is (so we can design it out).

On the next new product we will front load the engineering work; we will spend the needed time to do the up-front thinking; we will analyze; we will examine; we will weigh options; we will understand our designs. This time we will not just talk about the right work, this time we will do it.

On the next new product we will use our design reviews to hold ourselves accountable to the 50% reductions, to the investment in DFMA tools, to the training plan, to the front-loaded engineering work, to our commitment to our profitability and our country.

On the next new product we will celebrate the success of improved product functionality, improved product robustness, a tighter, more predictable supply chain, increased sales, increased profits, and increased US manufacturing jobs.

On the next new product we will do what it takes to manufacture products in the US because it’s the right thing for the country, and we will be more profitable because of it.

If you’d like some help improving the US economy one company at a time, send me an email (mike@shipulski.com), and I’ll help you put a plan together.

a

p.s. I’m holding a half-day workshop on how to implement systematic cost savings through product design on June 13 in Providence RI as part of the International Forum on DFMA — here’s the link. I hope to see you there.

I can name that tune in three notes.

More with more doesn’t cut it anymore, just not good enough.

More with more doesn’t cut it anymore, just not good enough.

The behavior we’re looking for can be nicely described by the old TV game show Name That Tune, where two contestants competed to guess the name of a song with the fewest notes. They were read a clue that described a song, and ratcheted down the notes needed to guess it. Here’s the nugget: they challenged themselves to do more with less, they were excited to do more with less, they were rewarded when they did more with less. The smartest, most knowledgeable contestants needed fewer notes. Let me say that again – the best contestants used the fewest notes.

In product design, the number of notes is analogous to part count, but the similarities end there. Those that use the fewest are not considered our best or our most knowledgeable, they’re not rewarded for their work, and our organizations don’t create excitement or a sense of challenge around using the fewest.

For other work, the number of notes is analogous to complexity. Acknowledge those that use the fewest, because their impact ripples through your company, and makes all your work easier.

Confusion of facts with feelings

Facts and feelings are different. Both are real, but facts are verifiable and feelings are not. Feelings are all about, well, feelings and facts are all about actions, events, and things that happened. But even with those differences, we still confuse them. And the consequences? We’re misunderstood and judged and, if the feelings are deep enough, we’re detoured to the off ramp of irreconcilable differences.

Facts and feelings are different. Both are real, but facts are verifiable and feelings are not. Feelings are all about, well, feelings and facts are all about actions, events, and things that happened. But even with those differences, we still confuse them. And the consequences? We’re misunderstood and judged and, if the feelings are deep enough, we’re detoured to the off ramp of irreconcilable differences.

But there’s a more interesting twist. Facts and feelings interact quite differently when looking back (past) versus looking forward (future).

When looking to the past, feelings modify facts and facts modify feelings. When feelings modify facts, events are colored, amped up, or muted, sequence is distorted. When facts do the bending, we become happy, sad, angry, or scared. The facts don’t really change (they don’t give a damn about feelings), but facts change our feelings, feelings change us, and we change the facts. It’s a natural coupling to acknowledge and work within.

When looking to the future, feelings dominate – feelings control our actions. In that way, feelings control what will happen, what will be. And the most dominant of all is fear. Fear stops us in our tracks, walls off possibilities, pulls us into inaction, and helps us mute ourselves. Fear restricts and limits.

We all want to broaden our possibilities, to free up the design space that is our lives. The self-help crew tells us to overcome our fears. That’s total bullshit. Fear is much too powerful for a full frontal attack. Fear is not overcome; it leaves when it’s good and ready. You don’t decide, it does. We must learn to live with fear.

Fear’s power is its ability to masquerade as reality. (How can it be reality if we’re afraid of a future that has not happened yet?) And what is fear afraid of? Fear is afraid to be seen as it is – as a feeling. And what are we supposed to do with feelings? Feel them. To live with fear we must acknowledge it. We must write it down, look at, and feel it. And then tread water with it while we create our future.

DoD’s Affordability Eyeball

The DoD wants to do the right thing. Secretary Gates wants to save $20B per year over the next five years and he’s tasked Dr. Ash Carter to get it done. In Carter’s September 14th memo titled: “Better Buying Power: Guidance for Obtaining Greater Efficiency and Productivity in Defense Spending” he writes strongly:

The DoD wants to do the right thing. Secretary Gates wants to save $20B per year over the next five years and he’s tasked Dr. Ash Carter to get it done. In Carter’s September 14th memo titled: “Better Buying Power: Guidance for Obtaining Greater Efficiency and Productivity in Defense Spending” he writes strongly:

…we have a continuing responsibility to procure the critical goods and services our forces need in the years ahead, but we will not have ever-increasing budgets to pay for them.

And, we must

DO MORE WITHOUT MORE.

I like it.

Of the DoD’s $700B yearly spend, $200B is spent on weapons, electronics, fuel, facilities, etc. and $200B on services. Carter lays out themes to reduce both flavors. On services, he plainly states that the DoD must put in place systems and processes. They’re largely missing. On weapons, electronics, etc., he lays out some good themes: rationalization of the portfolio, economical product rates, shorter program timelines, adjusted progress payments, and promotion of competition. I like those. However, his Affordability Mandate misses the mark.

Though his Affordability Mandate is the right idea, it’s steeped in the wrong mindset, steeped in emotional constraints that will limit success. Take a look at his language. He will require an affordability target at program start (Milestone A)

to be treated like a Key Performance Parameter (KPP) such as speed or power – a design parameter not to be sacrificed or comprised without my specific authority.

Implicit in his language is an assumption that performance will decrease with decreasing cost. More than that, he expects to approve cost reductions that actually sacrifice performance. (Only he can approve those.) Sadly, he’s been conditioned to believe it’s impossible to increase performance while decreasing cost. And because he does not believe it, he won’t ask for it, nor get it. I’m sure he’d be pissed if he knew the real deal.

The reality: The stuff he buys is radically over-designed, radically over-complex, and radically cost-bloated. Even without fancy engineering, significant cost reductions are possible. Figure out where the cost is and design it out. And the lower cost, lower complexity designs will work better (fewer things to break and fewer things to hose up in manufacturing). Couple that with strong engineering and improved analytical tools and cost reductions of 50% are likely. (Oh yes, and a nice side benefit of improved performance). That’s right, 50% cost reduction.

Look again at his language. At Milestone B, when a system’s detailed design is begun,

I will require a presentation of a systems engineering tradeoff analysis showing how cost varies as the major design parameters and time to complete are varied. This analysis would allow decisions to be made about how the system could be made less expensive without the loss of important capability.

Even after Milestone A’s batch of sacrificed of capability, at Milestone B he still expects to trade off more capability (albeit the lesser important kind) for cost reduction. Wrong mindset. At Milestone B, when engineers better understand their designs, he should expect another step function increase in performance and another step function decrease of cost. But, since he’s been conditioned to believe otherwise, he won’t ask for it. He’ll be pissed when he realizes what he’s leaving on the table.

For generations, DoD has asked contractors to improve performance without the least consideration of cost. Guess what they got? Exactly what they asked for – ultra-high performance with ultra-ultra-high cost. It’s a target rich environment. And, sadly, DoD has conditioned itself to believe increased performance must come with increased cost.

Carter is a sharp guy. No doubt. Anyone smart enough to reduce nuclear weapons has my admiration. (Thanks, Ash, for that work.) And if he’s smart enough to figure out the missile thing, he’s smart enough to figure out his contractors can increase performance and radically reduces costs at the same time. Just a matter of time.

There are two ways it could go: He could tell contractors how to do it or they could show him how it’s done. I know which one will feel better, but which will be better for business?

Be Purple

Focus, focus, focus. Measure, measure, measure. We draw organizational boxes, control volumes, and measure ins and outs. Cost, quality, delivery.

Focus, focus, focus. Measure, measure, measure. We draw organizational boxes, control volumes, and measure ins and outs. Cost, quality, delivery.

Control volumes? Open a Ziploc bag and pour water in it. The bag is the control volume and the water is the organizational ooze. Feel free to swim around in the bag, but don’t slip through it because you’ll cross an interface. You’ll get counted.

Organizational control volumes are important. They define our teams and how we optimize (within the control volumes). We optimize locally. But there’s more than one bag in our organizations.

The red team designs new products. They wear red shirts, red pants, and red hats. They do red things. We measure them on product function. The blue team makes products. They wear blue and do blue things. We measure them on product cost. Both are highly optimized within their bags, yet the system is suboptimal. Nothing crosses the interface – no information, no knowledge, no nothing. All we have is red and blue. What we need is purple.

We need people with enough courage to look up one level, put on a blue shirt and red pants, and optimize at the system level. We need people with enough credibility to swap their red hat for blue and pass information across the interface. We need trusted people to put on a purple jumpsuit and take responsibility for the interface.

Purple behavior cuts across the fabric of our metrics and control volumes, which makes it difficult and lonely. But, thankfully some are willing to be purple. And why do they do it? Because they know customers see only one color – purple.

Don’t bankrupt your suppliers – get Design Engineers involved.

Cost Out, Cost Down, Cost Reduction, Should Costing – you’ve heard about these programs. But they’re not what they seem. Under the guise of reducing product costs they steal profit margin from suppliers. The customer company increases quarterly profits while the supplier company loses profits and goes bankrupt. I don’t like this. Not only is this irresponsible behavior, it’s bad business. The savings are less than the cost of qualifying a new supplier. Shortsighted. Stupid.

Cost Out, Cost Down, Cost Reduction, Should Costing – you’ve heard about these programs. But they’re not what they seem. Under the guise of reducing product costs they steal profit margin from suppliers. The customer company increases quarterly profits while the supplier company loses profits and goes bankrupt. I don’t like this. Not only is this irresponsible behavior, it’s bad business. The savings are less than the cost of qualifying a new supplier. Shortsighted. Stupid.

The real way to do it is to design out product cost, to reduce the cost signature. Margin is created and shared with suppliers. Suppliers make more money when it’s done right. That’s right, I said more money. More dollars per part, and not more from the promise of increased sales. (Suppliers know that’s bullshit just as well as you, and you lose credibility when you use that line.) The Design Engineering community are the only folks that can pull this off.

Only the Design Engineers can eliminate features that create cost while retaining features that control function. More function, less cost. More margin for all. The trick: how to get Design Engineers involved.

There is a belief that Design Engineers want nothing to do with cost. Not true. Design Engineers would love to design out cost, but our organization doesn’t let us, nor do they expect us to. Too busy; too many products to launch; designing out cost takes too long. Too busy to save 25% of your material cost? Really? Run the numbers – material cost times volume times 25%. Takes too long? No, it’s actually faster. Manufacturing issues are designed out so the product hits the floor in full stride so Design Engineers can actually move onto designing the next product. (No one believes this.)

Truth is Design Engineers would love to design products with low cost signatures, but we don’t know how. It’s not that it’s difficult, it’s that no one ever taught us. What the Design Engineers need is an investment in the four Ts – tools, training, time, and a teacher.

Run the numbers. It’s worth the investment.

Material cost x Volume x 25%

The Improvement Mindset

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Improvement is good; we all want it. Whether it’s Continuous Improvement (CI), where goodness, however defined, is improved incrementally and continually, or Discontinuous Improvement (DI), where goodness is improved radically and steeply, we want it. But, it’s not enough to want it.

Improvement is good; we all want it. Whether it’s Continuous Improvement (CI), where goodness, however defined, is improved incrementally and continually, or Discontinuous Improvement (DI), where goodness is improved radically and steeply, we want it. But, it’s not enough to want it.

How do we create the Improvement Mindset, where the desire to make things better is a way of life? The traditional non-answer goes something like this: “Well, you know, a lot of diverse factors have to come together in a holistic way to make it happen. It takes everyone pulling in the same direction.” Crap. If I had to pick the secret ingredient that truly makes a difference it’s this:

a

People with the courage to see things as they are.

a

People who can hold up the mirror and see warts as warts and problems as problems – they’re the secret ingredient. No warts, no improvement. No problems, no improvement. And I’m not talking about calling out the benign problems. I’m talking about the deepest, darkest, most fundamental problems, problems some even see as strengths, core competencies, or even as competitive advantage. Problems so fundamental, and so wrong, most don’t see them, or dare see them.

The best-of-the-best can even acknowledge warts they themselves created. Big medicine. It’s easy to see warts or problems in others’ work, but it takes level 5 courage to call out the ugliness you created. Nothing is off limits with these folks, nothing left on the table. Wide open, no-holds-barred, full frontal assault on the biggest, baddest crap your company has to offer. It’s hard to do. Like telling a mother her baby is ugly – it’s one thing to think the baby is ugly, but it’s another thing altogether to open up your mouth and acknowledge it face-to-face, especially if you’re the father. (Disclaimer: To be clear, I do not recommend telling your spouse your new baby is ugly. Needless to say, some things MUST be left unsaid.)

It’s not always easy to be around the courageous souls willing to jeopardize their careers for the sake of improvement. And it takes level 5 courage to manage them. But, if you want your company to contract a terminal case of the Improvement Mindset, it’s a price you must pay.

Click this link for information on Mike’s upcoming workshop on Systematic DFMA Deployment

Pareto’s Three Lenses for Product Design

Axiom 1 – Time is short, so make sure you’re working on the most important stuff.

Axiom 1 – Time is short, so make sure you’re working on the most important stuff.

Axiom 2 – You can’t design out what you can’t see.

In product development, these two axioms can keep you out of trouble. They’re two sides of the same coin, but I’ll describe them one at a time and hope it comes together in the end.

With Axiom 1, how do you make sure you’re working on the most important stuff? We all know it’s function first – no learning there. But, sorry design engineers, it doesn’t end with function. You must also design for lean, for cost, and factory floor space. Great. More things to design for. Didn’t you say time was short? How the hell am I going to design for all that?

Now onto the seeing business of Axiom 2. If we agree that lean, cost, and factory floor space are the right stuff, we must “see it” if we are to design it out. See lean? See cost? See factory floor space? You’re nuts. How do you expect us to do that?

Pareto to the rescue – use Pareto charts to identify the most important stuff, to prioritize the work. With Pareto, it’s simple: work on the biggest bars at the expense of the smaller ones. But, Paretos of what?

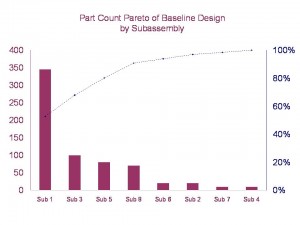

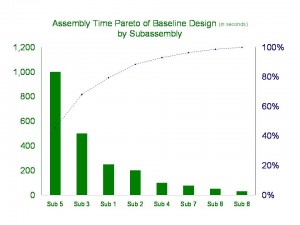

There is no such thing as a clean sheet design – all new product designs have a lineage. A new design is based on an existing design, a baseline design, with improvements made in several areas to realize more features or better function defined by the product specification. The Pareto charts are created from the baseline design to allow you to see the things to design out (Axiom 2). But what lenses to use to see lean, cost, and factory floor space?

Here are Pareto’s three lenses so see what must be seen:

To lean out lean out your factory, design out the parts. Parts create waste and part count is the surrogate for lean.

To design out cost, measure cost. Cost is the surrogate for cost.

To design out factory floor space, measure assembly time. Since factory floor space scales with assembly time, assembly time is the surrogate for factory floor space.

Now that your design engineers have created the right Pareto charts and can see with the right glasses, they’re ready to focus their efforts on the most important stuff. No boiling the ocean here. For lean, focus on part count of subassembly 1; for cost, focus on the cost of subassemblies 2 and 4; for floor space, focus on assembly time of subassembly 5. Leave the others alone.

Focus is important and difficult, but Pareto can help you see the light.

Tools for innovation and breaking intellectual inertia

Everyone wants growth – but how? We know innovation is a key to growth, but how do we do it? Be creative, break the rules, think out of the box, think real hard, innovate. Those words don’t help me. What do I do differently after hearing them?

Everyone wants growth – but how? We know innovation is a key to growth, but how do we do it? Be creative, break the rules, think out of the box, think real hard, innovate. Those words don’t help me. What do I do differently after hearing them?

I am a process person, processes help me. Why not use a process to improve innovation? Try this: set up a meeting with your best innovators and use “process” and “innovation” in the same sentence. They’ll laugh you off as someone that doesn’t know the front of a cat from the back. Take your time to regroup after their snide comments and go back to your innovators. This time tell them how manufacturing has greatly improved productivity and quality using formalized processes. List them – lean, Six Sigma, DFSS, and DFMA. I’m sure they’ll recognize some of the letters. Now tell them you think a formalized process can improve innovation productivity and quality. After the vapor lock and brain cramp subsides, tell them there is a proven process for improved innovation.

A process for innovation? Is this guy for real? Innovation cannot be taught or represented by a process. Innovation requires individuality of thinking. It’s a given right of innovators to approach it as they wish, kind of like freedom of speech where any encroachment on freedom is a slippery slope to censorship and stifled thinking. A process restricts, it standardizes, it squeezes out creativity and reduces individual self worth. People are either born with the capability to innovate, or they are not. While I agree that some are better than others at creating new ideas, innovation does not have to be governed by hunch, experience and trial and error. Innovation does not have to be like buying lottery tickets. I have personal experience using a good process to help stack the odds in my favor and help me do better innovation. One important function of the innovation process is to break intellectual inertia.

Intellectual inertia must be overcome if real, meaningful innovation is to come about. When intellectual inertia reigns, yesterday’s thinking carries the day. Yesterday’s thinking has the momentum of a steam train puffing and bellowing down the tracks. This old train of thought can only follow a single path – the worn tracks of yesteryear, and few things are powerful enough to derail it. To misquote Einstein:

The thinking that got us into this mess is not the thinking that gets us out of it.

The notion of intellectual inertia is the opposite of Einstein’s thinking. The intellectual inertia mantra: the thinking that worked before is the thinking that will work again. But how to break the inertia? Read the rest of this entry »

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski