Design for Six Sigma and Six Sigma Are Not Even Cousins

There is no question that Six Sigma helps companies make money. So much so that everyone in the manufacturing community knows the five hallowed letters: DMAIC (Define, Measure, Analyze, Improve, Control). It’s straightforward and fully wrung-out. But that’s not the case for the wicked step sister Design for Six Sigma (DFSS). She’s fundamentally different and more complicated. To start, it’s an alphabet soup out there. Here are some of the letters: DMADV, DMADOV, IDOV, and DMEDI, and there are likely more. Does everyone know these letters and what they stand for? Not me. But here is the fundamental difference: with DMAIC the thing to be improved already exists and with DFSS the thing to be created does not. In essence, there is no formalized problem to solve. So what you say?

With DMAIC it’s all about reducing variation relative to the specification; with DFSS there is no specification. In fact, there is no product yet a process on which we can measure variation. First the product itself must be created and its functional performance must be defined over a range of parameters. Only then is manufacturing variation measured relative to the range functional parameters (DMAIC). But I got ahead of myself.

Before creating the thing that does not exist and make sure it meets the functional specification, some mind reading of customer needs is required, an even lesser defined thing. So, there is a round of reading customers minds followed by round of creating something that does not exist to satisfy the customer needs define in the mind reading sessions. Oh yea, then the tolerances must be defined so the product always functions the way it’s supposed to. All this before we turn the DMAIC crank.

My point with all this is to help set expectations when dealing with product design/DFSS. It is wrong to expect the predictability and standardization of DMAIC when doing product design/DFSS. It’s different. Product design/DFSS is not the same turn-the-crank kind of operation. That is not to say there is zero predictability and standard work or that predictability is not something to strive for. It’s just different. With product design the problems are unknown at the start and sometime even the fundamental physics are unknown. Please keep this in mind when your product development projects are late relative to hyper aggressive, non-work-content-based schedules or when new products don’t meet the arbitrary cost targets.

Improving Product Robustness 101

Improving product robustness is straightforward and difficult. Here’s how to do it.

Identify specific failure modes, prioritize them, and go after the biggest ones first. Failure modes can be identified through multiple sources. Warranty data is sometimes coded by failure mode (more precisely, symptom type), so start there. The number one failure mode in this type of data is typically “no problem found”, so be ready for it. Analysis of the actual products that come back is another good way. Returned product is routed to the appropriate engineer who analyzes it and enters the failure mode into a database. A formal design FMEA generates a list of prioritized failure modes through the risk priority number (RPN), where larger is more important. To do this, engineers are hauled into a room and a facilitator helps them come up with potential failure modes. One caution – the process can generate many failure modes, more than you can fix, so make the top five or ten go away and don’t argue the bottom fifty. It makes no sense to even talk about number eleven if you haven’t fixed the top ten. But the best way I have found to identify failure modes (problems) that are meaningful to the customer is to ask the technical services group for their top five things to fix. They will give you the right answer because they interact daily with customers who have broken product. They won’t expect you to listen to them (you never listened before), so surprise them by fixing one or two on their list. They will be grateful you listened (they’ll likely want to buy you coffee for the rest of your career) and your customers will notice.

Once failure modes are identified, define the physics of failure – why the product breaks. This is tough work and requires focused thought and analysis. If, when you break the product, it “looks like” the ones coming back from the field, you have defined the physics of failure. This is the same thing as replicating the problem in the lab. Once that’s defined, create an automated test rig or experimental setup that breaks the product in a way that captures the physics of failure. I call this test rig a robustness surrogate because it stands in for the actual failure mode seen in the field. The robustness surrogate should break the product as fast as possible while retaining the physics of failure so you can break it and fix it many times before product launch. The robustness surrogate should be designed to break the product within minutes, not hours or days – the faster the better.

To know if product robustness is improved, the baseline (or existing) design is broken on the robustness surrogate. The new design must survive longer on the robustness surrogate than the baseline design. The result is A/B data (baseline design/ new design) that is presented at the design review using a simple bar graph format which I call big-bar-little-bar. Keep improving robustness of the new design even if it outperforms the baseline design by a factor of ten – that’s not good enough for your customers.

Don’t stop improving robustness until you run out of time, and don’t stop if you meet the arbitrary MTBF specification. Customers like improved robustness, and in this case too much of a good thing is wonderful.

Using this method, I reduced warranty cost per unit by 75% over a five year period. It worked.

Improve Product Robustness at the Expense of Predicting It

In a previous post I defined the term brand-damaging threshold and said I’d talk about how to improve product robustness. So, here goes.

Every company is at a different stage in their formalized product robustness efforts, so it’s challenging to talk meaningfully to everyone. But there are two especially meaningful principles that have served me well through the years.

I had the privilege of working with Don Clausing – Total Quality Design, The House of Quality, Enhanced QFD, and Robust Quality. I vividly remember the conversation where Don shared one of his secrets. As we watched a robustness test run, Don, in his terse way, barked out a guiding principle of improving product robustness. He said:

“Improve robustness at the expense of predicting it.”

I asked Don what the hell he meant (he liked to make his students work for it), and after some prodding, he went on to explain why it’s so important. He said people spend far too much time running tests to predict robustness and then spend even more time calculating mean time between failures (MTBF). If that’s not enough, then they spend time arguing about MTBFs and the confidence intervals. He said companies should dedicate all their time and energy improving robustness. “That’s what matters to the customer,” he said. And then he continued with something like: “Predicting robustness is worse than a simple waste of time.” (He wasn’t that polite.) But I still didn’t get it. What’s the big deal about predicting robustness? Read the rest of this entry »

Lack of product robustness can damage your brand

There are many definitions of product robustness and just as many formally trained specialists willing to argue about them. I get confused by all that complexity, I don’t like to argue, and I am not a specialist, I am a generalist. I like simplicity so I use operational definitions every chance I get. Here’s one for product robustness:

There are many definitions of product robustness and just as many formally trained specialists willing to argue about them. I get confused by all that complexity, I don’t like to argue, and I am not a specialist, I am a generalist. I like simplicity so I use operational definitions every chance I get. Here’s one for product robustness:

A customer walks up to your product, turns it on, and it works without breaking or getting in its own way.

Bad product robustness is bad for your brand. Very bad. Customers do not like when they pay money for a product and it doesn’t work, especially when they rely on those products to make money for themselves. And they remember the experience in a visceral way.

You can’t fix bad product robustness with great marketing; you can’t fix it with spin selling; you can’t tell customers you fixed it when you didn’t (since they use your product, they know the truth); and you can’t hide it because customers talk (so do competitors). There is no quick fix – it takes tools, time, training, and new thinking to improve product robustness. And when you do manage to fix it, customers won’t believe you until the see it for themselves. They don’t want to get burned again.

No product is infinitely robust, nor should it be. It doesn’t make financial sense. The product would be infinitely expensive and would take an infinite amount time to develop. But how much robustness is enough? An easier, and possibly more important, question to answer is – how much is too little? Or, stated another way, what is the minimum level of product robustness?

The specialists won’t agree with my assertion that there is a minimum threshold for product robustness, but I don’t care. I think there is one. I call this minimum value the brand-damaging threshold. Here’s an operational definition of product robustness that’s below the brand-damaging threshold:

Customers don’t buy your product because they know it breaks or gets in its own way and they go out of their way to tell others about it.

It is difficult to know when customers don’t buy, never mind know why they don’t. But there are some tell-tale signs that product robustness is below the brand-damaging threshold. Here are a few.

The CEO takes enough direct calls about products that don’t work to feel obligated to send you a thoughtfully-crafted, four word email saying something like “Fix that @#&% thing!” Customers have to be really pissed off to call the CEO directly, so the situation is bad. It’s also bad for a reason that’s closer to home – the CEO sent the email to you.

You get a little sick to your stomach when sales increase. You know you should be happy, but you’re not. Deep down you know you’ll see many of those products again because they’ll be sent back by angry customers, in pieces.

The volume of returns is so significant you create a refurbishment department. Or you create a new group to scavenge the reusable stuff off the piles of returned product. Not good signs.

Your product’s lack of robustness is the headline message in your customers’ marketing literature.

Now that the brand-damaging threshold is defined, the next logical topic is how to improve product robustness so it’s above the threshold. But that’s for another post.

Product Design – the most powerful (and missing) element of lean

Lean has been beneficial for many companies, helping improve competitiveness and profitability. But, lean has not been nearly as effective as it can be because there is a missing ingredient – product design. Where lean can reduce the waste of making and moving parts, product design can eliminate the parts altogether; where lean can reduce setup times for big machines, product design can change the parts so they no longer need the big machines; where lean can reduce inventory, product design can eliminate it by designing out parts; where lean can make the supply chain more efficient, product design can radically shorten it by designing out the long lead time elements.

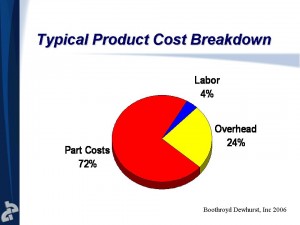

The power of product design is even more evident when considering the breakdown of product cost. Here is some data from Nick Dewhurst taken from multiple-hundred DFMA analyses showing the typical cost breakdown of products.

Of the three buckets of cost, material cost is by far the largest 74%, and this is where product development shines. Product design can eliminate 40 to 50% of material cost resulting in radical cost savings. Lean cannot. I will go a bit further and say that material cost reductions are largely off limits to the lean folks since it requires fundamental product changes.

Side note – Probably most surprising about cost breakdown data is labor cost is only 4%. Why we move our manufacturing to “low cost countires” to chase 50% labor reductions to net a whopping 2% cost reduction is beyond me, but that’s for a different post.

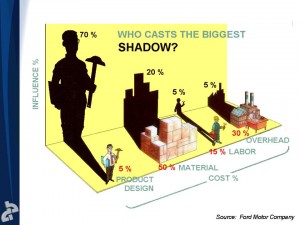

Let’s face it – material cost reduction is where it’s at, and lean does not have the toolbox to reduce material cost. There’s no mystery here. What is mysterious, however, is that companies looking to survive at all costs are not pulling the biggest lever at their disposal – product design. Here is a bit of old data from Ford showing that Product Design has the biggest lever on cost. We’ve know this for a long time, but we still don’t do it.

Clearly, the best approach of is to combine the power of product design with lean. It goes like this: the engineers design a low cost, low waste product that is introduced to the production line, and the lean folks improve efficiency and reduce cost from there. We’ve got the lean part down, but not the product design part.

There are two things in the way of designing low cost, low waste products in a way that helps take lean to the next level. First, product development teams don’t know how to do the work. To overcome this, train them in DFMA. Second, and most important, company leaders don’t give the product development teams the tools, time, and training to do the work. Company leaders won’t take the time to do the work because they think it will delay product launches. Also, they don’t want to invest in the tools and training because the cost is too high, even though a little math shows the investment is more than paid back with the first product launch. To fix that, educate them on the methods, the resource needs, and the savings.

Good luck.

Want More New Products? Reduce Capacity Utilization

Congratulations. You’ve managed to keep your product development engine running. Good work. But now the hard part. Marketing and sales know new products are a key to profitability, and so does the CEO. So they’ve all asked for more new products, and now you have more active product development projects in the pipeline. The product development folks will do whatever they can to crank out the products. But can they get it done?

When does the product pipeline become too much for your product development engine to handle? We all know you can’t keep adding more new product development projects without adding capacity or improving productivity. Sure you can ask your product development engine to do more (and more), and it will try; but at some point it will run out of gas. So, ask yourself: Has your product development engine run out of gas? How can you tell? If it hasn’t, do you know how many miles are left in the tank?

If you don’t measure it you can’t improve it, that’s what the black belts say. But what to measure? What are the right metrics to tell you if your product development engine is out of gas? One of the best books on the subject is Managing the Design Factory, by Don Reinertsen. The rest of the post is strongly shaped by Don’s book, if not taken directly from it. Remember, genius steals.

The best metrics are simple, relevant to the objective, and are leading indicators. Simple so they’re easy to interpret; relevant so they move you toward the objective, in this case launching more new products; and are leading indicators, in that they are predictors of outcomes, so you can take action before catastrophic outcomes occur. Here are three good ones. Read the rest of this entry »

Make it worse and do the opposite

It’s time to write, but, again, no topic. This writing-once-a-week thing is tough. I drop my son off at the hockey rink and walk back to the parking lot to write in my car (I’m telling you, this is a good place to write). Before I get to my car, my cell phone rings. It’s a teacher friend of mine. He’s the guy at the high school who helps kids work out issues with substance use/abuse and related topics. He’s a real pro – every high school should have a person of his caliber. Without introducing himself, he says, “You want to go for a hike tomorrow?” “I have to work,” I say. “It’s Veteran’s Day,” he says. “Yeah, I know, and I have to work,” I reply. “Oh ya, I forgot about that,” he says with a chuckle.

My mind clicks and I remember a discussion we had the previous week while on a walk. I ask, “Do you remember talking about that trick to break intellectual inertia?” “Ya, we talked about how I used it to help a kid work himself out of some destructive behavior. Make it worse and do the opposite,” he says. “I love it; it works great,” he says. I now have my topic. We talk for a while and he helps my thinking converge. This one is a joint effort.

Here’s the problem: problems are stressful. We have a physiological reaction to problems; adrenaline rushes through our veins; our blood pressure increases; our heart rate increases; we get flushed. This is real. It’s run or attack, flight or fight. Our mental processing is all about survival. And there is real reason for concern; there are real consequences to not solving a problem – your reputation, your authority, your job. Read the rest of this entry »

Our New Normal, it’s all-you-can-eat

Our New Normal is crazy. Competitors are chewing voraciously on each other, so are suppliers and their customers; there is immense pressure to launch more products; and radical cost cutting is required just to stay in business. It’s official, the engine is running at its rev limit. The wick is turned up. We’re running wide-open.

Our New Normal is crazy. Competitors are chewing voraciously on each other, so are suppliers and their customers; there is immense pressure to launch more products; and radical cost cutting is required just to stay in business. It’s official, the engine is running at its rev limit. The wick is turned up. We’re running wide-open.

Your people are tired and stressed, but they won’t admit it openly. They are too concerned about losing their jobs. They know anyone looking for a job is hosed. The consequences? One word – FORECLOSURE. They will do whatever it takes to keep their jobs.

We are not infinite capacity beings, so there are limits to “whatever it takes”. Your people will not work 25 hours a day 8 days a week. They may sit at their desk more than before, but I assure you they’re not getting more done. They’re just sitting there more. That’s all. In fact, they’re spending most of their emotional energy trying to keep their heads down and trying to stay off the critical path. There is likely more activity, but less progress. Certainly there is more stress. This is not healthy or productive.

Most troubling is that our New Normal makes it impossible to say “no”. New Normal is really code for “can’t say no to anything”. Say no and you may lose your job. So guess what? No one says no. Read the rest of this entry »

Tools, training, time, and a great piano teacher

It was Monday night after dinner. My thirteen year old son and I got in the car and started on the drive to hockey practice. I drove and he texted. I was in the middle a struggle to come up with a topic for this post. My son finished a text, snapped his phone shut, and blurted out “Mozart wrote a note to his dad. He told him that he thought silence was the most important part of music.” I responded, “Really.” “He was a rule breaker,” he said. He paused then continued, “The music of the time was smooth with a regular pattern. But he did things that weren’t pleasing to the ear like using 7th notes and Bs right next to B flats. Do you know what else he did?” “No,” I said. “He put a fermata right in the middle of one of his pieces. That’s a rest that’s as long as you want it to be. When you use a fermata you can stop, go out and get a cup of coffee, and come back later and start playing and that’s okay.” “Really,” I said.

It was Monday night after dinner. My thirteen year old son and I got in the car and started on the drive to hockey practice. I drove and he texted. I was in the middle a struggle to come up with a topic for this post. My son finished a text, snapped his phone shut, and blurted out “Mozart wrote a note to his dad. He told him that he thought silence was the most important part of music.” I responded, “Really.” “He was a rule breaker,” he said. He paused then continued, “The music of the time was smooth with a regular pattern. But he did things that weren’t pleasing to the ear like using 7th notes and Bs right next to B flats. Do you know what else he did?” “No,” I said. “He put a fermata right in the middle of one of his pieces. That’s a rest that’s as long as you want it to be. When you use a fermata you can stop, go out and get a cup of coffee, and come back later and start playing and that’s okay.” “Really,” I said.

I dropped him off at the rink and pulled into a parking spot so I could write in the car (don’t knock it until you try it). I jotted down some scattered thoughts, and it hit me. Jackie! It was Jackie. His piano teacher was behind all this. That morning she taught him about Mozart. I now had my topic.

Jackie is a great piano teacher – really great. Sure, she’s got the pedigree, but more importantly she has the ability to reach my son. She can help him grow his thinking, help him think differently, help him build new thinking for himself. And this new thinking isn’t the kind that stops at his head, but makes it all the way into his chest. He feels this new thinking in his chest. We can learn a lot from Jackie. I want to look at her system for teaching new thinking, which she does under the cover of teaching piano, and compare it to how we improve our engineering thinking under cover of developing new products. Sounds like a stretch, I know, but I’ll take a shot at it.

The framework for Jackie’s system can be described by the three Ts – tools, training, and time. Let’s start with tools. Read the rest of this entry »

Problems are good

Everyone laughs at the person who says “We don’t have problems, we have opportunities.” Why do we say that? We know that’s crap. We have problems; problems are real; and it’s okay to call them by name. In fact, it’s healthy. Problems are good. Problems focus our thinking. There is a serious and important nature to the word problem, and it sets the right tone. Everyone knows if the situation has risen to the level of a problem it’s important and action must be taken. People feel good about organizing themselves around a problem – problems help rally the troops.

In a previous post on innovation, I talked about the tight linkage between problems and innovation. In the pre-innovation state there is a problem; in the post-innovation state there is no problem. The work in the middle is a good description of the thing we call innovation. It could also be called problem solving.

Behind every successful product launch is a collection of solved problems. The engineering team defines the problems, understands the physics, changed the design, and makes problems go away. Behind every unsuccessful product launch is at least one unsolved problem. These unsolved problems disrupt product launches – limiting product function, delaying launches, and cancelling others altogether. All this can be caused by a single unsolved problem. Read the rest of this entry »

It’s a tough time to be a CEO

2009 is a tough year, especially for CEOs.

CEOs have a strong desire to do what it takes to deliver shareholder value, but that’s coupled with a deep concern that tough decisions may dismantle the company in the process.

Here is the state-of-affairs:

Sales are down and money is tight. There is severe pressure to cut costs including those that are linked to sales – marketing budgets, sales budgets, travel – and things that directly impact customers – technical service, product manuals, translations, and warranty.

Pricing pressure is staggering. Customers are exerting their buying power – since so few are buying they want to name their price (and can). Suppliers, especially the big ones, are using their muscle to raise prices.

Capacity utilization is ultra-low, so the bounce-back of new equipment sales is a long way off.

Everyone wants to expand into new markets to increase sales, but this is a particularly daunting task with competitors hunkering down to retain market share, cuts in sales and marketing budgets, and hobbled product development engines.

There is a desire to improve factory efficiency to cut costs (rather than to increase throughput like in 2008), but no one wants to spend money to make money – payback must be measured in milliseconds.

So what’s a CEO to do? Read the rest of this entry »

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski