Who owns cost?

I’ve heard product cost is designed in; I’ve heard it happens at the early stages of product development; And, I’ve heard, once designed in, cost is difficult get out. I’m sure you’ve heard this before. Nothing new here. But, is it true? Is cost really designed in? Why do I ask? Because we don’t behave like it’s true. Because was it was true, the Design community would be responsible for product costs. And they’re not.

I’ve heard product cost is designed in; I’ve heard it happens at the early stages of product development; And, I’ve heard, once designed in, cost is difficult get out. I’m sure you’ve heard this before. Nothing new here. But, is it true? Is cost really designed in? Why do I ask? Because we don’t behave like it’s true. Because was it was true, the Design community would be responsible for product costs. And they’re not.

Who gets flogged when the cost of new products are too high? Manufacturing. Who does not? Design. Who gets stuck running cost reduction projects when costs are too high? Manufacturing. Who does not? Design. Who gets the honor of running kaizens when value stream maps don’t have enough value? Manufacturing. Who designs out the value and designs in the cost? Design. (That’s why they’re called Design.) If Design designs it in, why is the cost albatross hung around Manufacturing’s neck?

It sucks to be a manufacturing engineer – all the responsibility to reduce cost without the authority to do it. The manufacturing engineers’ call to arms –

a

Reduce cost, but don’t change anything!

a

Say that out loud. Reduce the cost, but don’t change anything. How stupid is that? We’ll it’s pretty stupid, but it happens every day. And why constrain the manufacturing engineers like that? Because they don’t have the authority to change the product design – only Design can do that. So you’re saying Manufacturing is responsible for product cost, but they cannot change the very thing that creates all the cost? Yes.

What would life be like if we behaved as if Design was responsible for product cost? To start, Design would present product cost data at new product development gate reviews. Design would hang their heads when product costs were higher than the cost target, and they would be held accountable for redesigning the product and meeting the cost target. (They would also be given the tools, time, and training to do the work.)

Going forward, Design would understand the elements of product that create the most cost. And how would they know this? First, they would spend some time on the production floor. (I know this is a little passé, but it still works.) Second, they would do Design for Assembly (DFA) in a hands-on, part-by-part, piece-by-piece way. No kidding, they would handle all the parts themselves, assemble them with production tooling, and score the design with DFA. That’s right, Design would do DFA. The D in DFA does not stand for Advanced Manufacturing, Operations, Supplier Quality, Purchasing, or Industrial Engineering. The D stands for Design.

I know your manufacturing engineers are in favor of rightly burdening Design with responsibility for product cost. But, your Lean Leaders should be the loudest advocates. Imagine if your Design organization designed new products with half the parts and half the material cost, and your Lean Leaders reduced value waste from there. Check that, Lean Leaders should not be the loudest advocates. Your stockholders should be.

Click this link for information on Mike’s upcoming workshop on Systematic DFMA Deployment

If you were a country, what would you do?

If I was a country I would care about the well-being of my people. I would truly care about the health, education, and happiness of my families. That’s easy to say, but hard to pay for. How would I fund it? I would make stuff, lots of stuff. My rationale – jobs, lots of jobs. I would create a sustainable economy built on the bedrock of manufacturing. I’m not talking about designing things, but actually making them, with real factories, real machines, and real people, because as a country, it’s more important to make things than to design them.

If I was a country I would care about the well-being of my people. I would truly care about the health, education, and happiness of my families. That’s easy to say, but hard to pay for. How would I fund it? I would make stuff, lots of stuff. My rationale – jobs, lots of jobs. I would create a sustainable economy built on the bedrock of manufacturing. I’m not talking about designing things, but actually making them, with real factories, real machines, and real people, because as a country, it’s more important to make things than to design them.

The single most important equation for me as a country is

Price – Cost = Profit.

While companies care most about profit, as a country I care most about cost – manufacturing cost. I want to incur the cost of manufacturing within my borders, and for good reason – that’s where jobs and money are. For a product that sells for $100 with a 20% profit margin, costs ($80) are four times larger than profits ($20). No big deal you say? Pretend you are a country and look at the three components of cost from my perspective – labor, materials, and overhead, and then ask yourself if it’s a big deal.

Labor

My people get paid for their time. (For me, as a country, that’s magic.) They buy food, clothing, and shelter and have a little fun. In turn, they pay me income tax, which I use to educate my children.

Material

My dirt, rocks, and sticks are used in products and my people get paid to dig, move, mix, and cut. (More magic.) And the machines to do it all are made by my people. We then make the same trade as above – they buy food, clothes, shelter, they pay me income taxes, and I use the money to pay for healthcare.

Overhead

My dirt, rocks, and sticks are dug and moved to make electricity. My people get paid, they spend, and I provide services. A good trade for all.

I’m not an economist, and I’m oversimplifying things. And I know there’s more than a hint of nationalism here. But, even still, when I pretend to be a country, all this makes sense to me.

If you were a country, what would you do?

Click this link for information on Mike’s upcoming workshop on Systematic DFMA Deployment

Ready, Fire, Aim.

Pent up demand is everywhere. After almost two years of cutting inventories and pushing out purchases, companies are ready to buy. And with credit coming back on line, they’re ready to buy in bulk. Good news? No, great news. We’re back on our growth path. And that’s good because Wall Street now expects growth. But, together this wicked couple of pent up demand and Wall Street’s appetite for immediate growth has created a powder keg that’s ready to blow.

Pent up demand is everywhere. After almost two years of cutting inventories and pushing out purchases, companies are ready to buy. And with credit coming back on line, they’re ready to buy in bulk. Good news? No, great news. We’re back on our growth path. And that’s good because Wall Street now expects growth. But, together this wicked couple of pent up demand and Wall Street’s appetite for immediate growth has created a powder keg that’s ready to blow.

Companies want more new products to satisfy the pent up demand (and Wall Street). Growth through new products is a theme heard around the globe; there’s a relentless push for more products – early and often. Resources be damned, best practices be damned, we’re going to launch more products. Were going to market and will fix it later. The battle cry – Don’t launch, don’t sell!. However, the real battle cry is more aptly – Ready, fire, aim! We’re going too fast.

I’m all for productivity, but we’re heading for a cliff, a cliff some have already accelerated off of, albeit in an unintended way.

a

We’ve forgotten the golden rule – provide value to customers, or you’re hosed.

a

Customers value function, or “what it does”. Function first. But in this need-for-speed environment that’s just what’s at risk. To reduce time to market, we eliminate tasks (best practices?) in our product development processes. All good unless we eliminate tasks that make the product function as intended. All good unless we load our engineers so heavily they don’t have time to design in functionality. We must be careful here. If you’re first to market and your product doesn’t work, you should have waited.

I believe launching too early is worse than launching too late because a botched launch can damage your brand, the brand you’ve taken years to build. (Click this link to see a post on brand damaging.) As we know, word gets around when your product doesn’t work (or accelerates on its own).

Satisfying the siren of pent up demand can run you into the rocks if you’re not careful. So block your ears to her song, and take the time to get your products right.

Custom Model, exploring customized manufacturing (Mechanical Engineering Magazine)

By reducing parts count and easing assembly, one plasma cutter maker explores customized manufacturing.

By reducing parts count and easing assembly, one plasma cutter maker explores customized manufacturing.

By Jean Thilmany, Associate Editor, Mechanical Engineering Magazine

Ask nearly any engineer or manufacturer about customized manufacturing and—to a person—they’ll all say the same thing: Have you heard the Dell story?

Dell is offered up again and again as the number one example of customized manufacturing done right and done successfully. Shortly after its founding in 1984, Dell began what it calls a configure-to-order approach to manufacturing. The computer company lets customers customize their own computers on the Dell Web site. Buyers select how much memory and disk space they desire and the resulting computer is manufactured and shipped to them.

The approach has helped the computer maker see skyrocket growth. Last year, it held the second-highest spot for desktops and laptops shipped, behind Hewlett Packard, according to market-share numbers from research firm International Data Corp. in Framingham, Mass.

Manufacturers—particularly electronics manufacturers—have long been taking notice. Many of them are investigating how the configure-to-order model could be put to use at their own companies. And some of them have implemented the method—along with the necessary software to get the job done—with great success.

Take Hypertherm Inc. of Hanover, N.H., maker of plasma metal cutting equipment. The company has recently started allowing customers to choose online from ten CNC Edge Pro product configurations, up from three configurations in the former product line, said John Sobr, head designer on the project.

Hypertherm recently redesigned its plasma metal cutting equipment to reduce part count by 27 percent while doubling the number of inputs available. Customers can now choose from ten product configurations.

DFMA Won’t Work

Ask a company or team to do DFMA, and you get a great list of excuses on why DFMA is not applicable and won’t work. Product volumes are too low for DFMA, or too high; product costs are too low, or too high; production processes are too simple, or complex; production mix is too low, or too high. That’s all crap – just excuses to get out of doing the work. DFMA is applicable; it’s just a question of how to prioritize the work.

Ask a company or team to do DFMA, and you get a great list of excuses on why DFMA is not applicable and won’t work. Product volumes are too low for DFMA, or too high; product costs are too low, or too high; production processes are too simple, or complex; production mix is too low, or too high. That’s all crap – just excuses to get out of doing the work. DFMA is applicable; it’s just a question of how to prioritize the work.

To prioritize the work, take a look at product volumes. They’ll put you in the right ballpark. Here are three categories, low, medium, and high volume:

Our Misguided Focus on Patents

Is it patented? Can we patent that? We need a @#!$%& patent and we need it now! You hear that a lot these days. Everyone wants to be part of the new economy, the thinking economy, and patents are the key, right? No.

Is it patented? Can we patent that? We need a @#!$%& patent and we need it now! You hear that a lot these days. Everyone wants to be part of the new economy, the thinking economy, and patents are the key, right? No.

Patents are the results of something – good, old-fashioned innovation. The big mistake companies make is to focus directly on patents instead of focusing on innovation which can then be patented. Sounds like a subtle difference, but it’s as subtle as the difference between lightning and lightning bug. (Stolen from Mark Twain.)

Patents are the currency of innovation, not the innovation itself, just as our paper money is the currency for wealth, and not the gold reserve itself. We use paper money to stand for the gold, but, implicitly, there’s wealth backing it up. Just as it’s misguided for a country to print money without something to back it up (strong gold reserves), it’s misguided for a company to create patents without something to back them up – innovative technologies, technologies that make a difference to the customer.

Innovation is the gold that backs up patents, the currency of innovation.

Would you rather have lots of paper money and no gold, or lots of gold that allows you to print lots of money? We get this one wrong when we focus on paper patents instead of golden innovation. Why do we mess it up? Because printing money and filing patents are easy, and digging gold and doing innovation are hard. Patents are fast and innovation is slow. Companies want the free lunch, there’s no such thing.

What to do when there are no patents? Do innovation. What to do when there is no time to do innovation? Do innovation. What to do when there is no money to do innovation? Do innovation. What to do? Do innovation.

The road to a full portfolio of innovative technologies is a long one, but it’s paved with gold.

The Innovation Edict

There is a groundswell of interest in innovation across the planet. As historians know, the interest in innovation is cyclic, and this year it’s surely in vogue. Everyone wants more of it, even if we don’t know what it is – we want it. And we want it because we want it; it’s an emotional want. Never mind that we don’t know how to do it, damn it, we’re going to do more innovation come hell or high water. Not knowing how to do innovation is an obstacle, but it can be overcome with the right tools, processes and a good training plan. Our people are capable and willing, so there’s no problem there. But there is a show-stopper out there: the innovation edict is incremental work – it’s another thick layer of work slopped onto our already full plates. Even before the innovation edict, we’re doing two or three jobs, we’ve extended the do-more-with-less mantra beyond the ridiculous, and we’re stretched to the breaking point with workloads that defy all tests of reason. How can we be expected to do more?

There is a groundswell of interest in innovation across the planet. As historians know, the interest in innovation is cyclic, and this year it’s surely in vogue. Everyone wants more of it, even if we don’t know what it is – we want it. And we want it because we want it; it’s an emotional want. Never mind that we don’t know how to do it, damn it, we’re going to do more innovation come hell or high water. Not knowing how to do innovation is an obstacle, but it can be overcome with the right tools, processes and a good training plan. Our people are capable and willing, so there’s no problem there. But there is a show-stopper out there: the innovation edict is incremental work – it’s another thick layer of work slopped onto our already full plates. Even before the innovation edict, we’re doing two or three jobs, we’ve extended the do-more-with-less mantra beyond the ridiculous, and we’re stretched to the breaking point with workloads that defy all tests of reason. How can we be expected to do more?

The truth of the matter is we cannot do more; we’re already diluted beyond all effectiveness. Any more dilution would be like watering down water with more water. It has no meaning. And what makes the innovation edict especially ludicrous is that innovation requires a lot of thinking time, quality thinking time, uninterrupted thinking time. It’s a thinking person’s sport. And not just mortal thinking, it requires novel thinking, thinking we’ve never done before. Do you have time to think with your current workload? I don’t think so.

Thinking? You’re crazy. We don’t have time to think, we need to do innovation!

As we know, managers have extreme difficulty discerning activity from progress, and not many think that thinking is progress. It sure doesn’t look like activity. If you want to aggravate a manager, sit at your desk and think. When they ask you what you’re doing, tell them you’re thinking. Then watch their face turn colors like a New England foliage.

What do we do about it? The answer comes from Jim Collins – create a stop doing list. We must create innovation bandwidth by stopping work on lower priority activities. Stop. Stop. Stop. And don’t just talk about stopping, actually stop doing things. It’s the only way. Of course this is difficult because it requires prioritization. It requires judgment and guts. And feelings will get hurt because some projects will stop. So be it. Actually, I think major disagreement, anger, and long, difficult meetings are objective evidence that activities are actually stopping. No anger, no difficult meetings, no freed up innovation bandwidth. Do you want to do innovation or just talk about doing innovation?

There’s no free lunch with innovation. Innovation requires our most precious resource – our time.

DFMA to Control Controller Design – Design2Part Magazine

Design for Manufacture and Assembly is reported to improve CNC performance, modularity, durability, and serviceability

When Hypertherm (www.hypertherm.com) was getting ready to design its next generation of metal cutting CNCs, the engineering team’s goal was to make improvements. But the controllers, which automate the Hanover, New Hampshire-based company’s advanced cutting tools and systems, were already well-accepted in the marketplace and highly regarded in the industry. So why redesign? And how would they go about it?

See this link for the full article – Using DFMA to Control Controller Design

Discontinuous Improvement at the Expense of Continuous Improvement

Five percent here, three percent there. I’m tired as hell of continuous improvement. Sure there’s a place for it, but it shouldn’t be the only type of work we do. But, unfortunately, that’s just what’s happened in manufacturing. To secure the balance sheet, the pendulum swung too far toward continuous improvement. Just look at what we’re writing about – the next low cost country, shorter lead times, how to be profitable where there’s no profit to be had. Those topics scream continuous improvement – take nickels and dimes out of processes to increase profits. But there’s a dark side to all this focus on continuous improvement. It has created a big problem: it has come at the expense of discontinuous improvement.

Five percent here, three percent there. I’m tired as hell of continuous improvement. Sure there’s a place for it, but it shouldn’t be the only type of work we do. But, unfortunately, that’s just what’s happened in manufacturing. To secure the balance sheet, the pendulum swung too far toward continuous improvement. Just look at what we’re writing about – the next low cost country, shorter lead times, how to be profitable where there’s no profit to be had. Those topics scream continuous improvement – take nickels and dimes out of processes to increase profits. But there’s a dark side to all this focus on continuous improvement. It has created a big problem: it has come at the expense of discontinuous improvement.

Continuous improvement is a philosophy of minimization with a focus on cost and waste reduction, while discontinuous improvement is a philosophy of maximization with a focus on creation of new markets through product innovation. As of late, we’ve minimized waste at the expense of invention and innovation. I propose we flip this on its head and maximize through discontinuous improvement at the expense of continuous improvement. That’s right; I said do less lean and Six Sigma.

But we must ask ourselves if we’re capable of doing discontinuous improvement. Remember, we ignored or dismantled our innovation engines over the last years. And what about our big thinkers, our creative thinkers, our innovators? Do they still work for us, or have they just stopped talking about big ideas? I urge you to answer that question because your next actions depend on it.

If your innovative thinkers are gone, go out and hire the best you can find ASAP. If you were fortunate enough to retain your big thinkers, congratulations. Now it’s time to get the band back together, but first you’ve got to do some reconnaissance to ferret them out of their hiding places. Once you find them, invite them to a nice lunch – the nicer the better. Don’t push too hard at lunch, just start to get reacquainted. In time you’ll get to talk about their ideas on new technologies and how to create new markets.

It will be difficult to get your company swing the pendulum away from continuous improvement, but you must try. Without discontinuous improvement your company will be destined to wrestle for nickels using lean and Six Sigma.

Keynote Presentation – DFMA for Discontinuous Improvement and Innovation

Tuesday, June 15th, 2010

Tuesday, June 15th, 2010

9:30 a.m. to 10:30 a.m.

Keynote Presentation

2010 INTERNATIONAL FORUM on Design for Manufacturing and Assembly

Providence, Rhode Island, USA

DFMA for Discontinuous Improvement and Innovation

Abstract

The literature is full of examples of companies using DFMA to design lower cost products. Though the savings are radical in magnitude, there is a general misconception that DFMA is most like continuous improvement work with regular installments of small improvements. This thinking does DFMA an injustice, as the DFMA process drives creative solutions, radical changes, discontinuous improvement, and innovation. The paper describes how to use DFMA to define areas for discontinuous improvement and innovation, how to create a design approach, and how to define and execute a project plan to achieve radical improvement.

Presenter

Dr. Mike Shipulski

For the past six years as Director of Engineering at Hypertherm, Inc., Mike has had the responsibilities of product development, technology development, sustaining engineering, engineering talent development, engineering labs, and intellectual property. Before Hypertherm, Mike worked in a manufacturing start‐up as the Director of Manufacturing and at General Electric’s R&D center as a Manufacturing Scientist during the start‐up phase of GE’s Six Sigma efforts. Mike received a Ph.D. in Manufacturing Engineering from Worcester Polytechnic Institute. Mike is the winner of the 2006 DFMA Supporter of the Year, and has been a keynote presenter at the DFMA Forum since 2006.

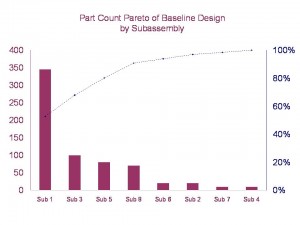

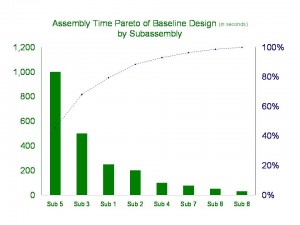

Pareto’s Three Lenses for Product Design

Axiom 1 – Time is short, so make sure you’re working on the most important stuff.

Axiom 1 – Time is short, so make sure you’re working on the most important stuff.

Axiom 2 – You can’t design out what you can’t see.

In product development, these two axioms can keep you out of trouble. They’re two sides of the same coin, but I’ll describe them one at a time and hope it comes together in the end.

With Axiom 1, how do you make sure you’re working on the most important stuff? We all know it’s function first – no learning there. But, sorry design engineers, it doesn’t end with function. You must also design for lean, for cost, and factory floor space. Great. More things to design for. Didn’t you say time was short? How the hell am I going to design for all that?

Now onto the seeing business of Axiom 2. If we agree that lean, cost, and factory floor space are the right stuff, we must “see it” if we are to design it out. See lean? See cost? See factory floor space? You’re nuts. How do you expect us to do that?

Pareto to the rescue – use Pareto charts to identify the most important stuff, to prioritize the work. With Pareto, it’s simple: work on the biggest bars at the expense of the smaller ones. But, Paretos of what?

There is no such thing as a clean sheet design – all new product designs have a lineage. A new design is based on an existing design, a baseline design, with improvements made in several areas to realize more features or better function defined by the product specification. The Pareto charts are created from the baseline design to allow you to see the things to design out (Axiom 2). But what lenses to use to see lean, cost, and factory floor space?

Here are Pareto’s three lenses so see what must be seen:

To lean out lean out your factory, design out the parts. Parts create waste and part count is the surrogate for lean.

To design out cost, measure cost. Cost is the surrogate for cost.

To design out factory floor space, measure assembly time. Since factory floor space scales with assembly time, assembly time is the surrogate for factory floor space.

Now that your design engineers have created the right Pareto charts and can see with the right glasses, they’re ready to focus their efforts on the most important stuff. No boiling the ocean here. For lean, focus on part count of subassembly 1; for cost, focus on the cost of subassemblies 2 and 4; for floor space, focus on assembly time of subassembly 5. Leave the others alone.

Focus is important and difficult, but Pareto can help you see the light.

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski