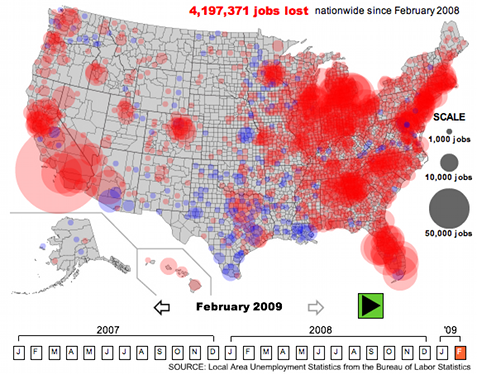

The Job Loss Implosion

If you do one thing, click this link. (Or the graphic itself.) Please. You’ll be sent to a page where you can watch an animation of US job losses. I was debilitated after watching the implosion.

Here’s how I reacted to the animation:

Disbelief. No way. Not real. I checked the data. It’s real.

Fear. Look what happened to my country!

Anger. Why isn’t everyone talking about this? Why aren’t we doing something about this? Why are we saying the economy is on the mend? That’s crap, I-want-to-get-reelected type crap. (To be clear, I think great progress has been made.) Truth is it cannot be mended with the current approach. It cannot. If possible at all, it will take a borderline-Draconian approach, where cuts are made and taxes are raised to radically fund innovation, technology, and manufacturing. (Think energy, energy, energy.) Reinvestment in ourselves.

Sadness. Our lifestyle, as we know it, is over. The American Way has imploded; we just don’t have the courage to face it yet.

Sadness. This is not good for my kids. (And that’s when I changed my thinking.)

Hope. We can do something about this. It will be exceedingly difficult, but we can do it. We’re smart enough. We’ll have to make hard choices, choices where we get less and pay more – a net reduction in our standard of living. It will take sacrifice, real sacrifice. Sacrifice at the standard of living level, sacrifice inline with WWII-caliber, go-without sacrifice. Sacrifice to free up radical amounts of money to invest in our country, in our innovation, in our technology, and in ourselves. I’m talking about self-investment at levels that make the Apollo Program look like chump change, self-investment that makes the war look like a bargain. The toughest part, however, is how to elect politicians on a platform of get less and pay more, a platform of sacrifice, of tough choices. I’m not talking about talking about tough choices, but actually making tough choices, choices for the common good. I’m talking about a platform that demands true, unselfish behavior by all.

Action. I will write to raise awareness. I will post to raise awareness. I will tweet to raise awareness. I will speak (if not yell) to raise awareness. I will continue to educate on how to fix it. I will reach out to people who can make a difference. I will pester them. I will pester them again. For my kids and yours, I will not give up.

What will you do?

Daily tweets will start today.

Starting today I will be sending out a daily tweet (five per week.) I’ll comment on interesting web content or send a short thought. The content will be in line with my blog posts — innovation, product development, the economy, people, and teams.

Starting today I will be sending out a daily tweet (five per week.) I’ll comment on interesting web content or send a short thought. The content will be in line with my blog posts — innovation, product development, the economy, people, and teams.

To follow me on Twitter and receive my daily tweets, click this link — @MikeShipulski. Or, click on the small Twitter icon just above my head.

Please forward this note to those that may want to get my tweets.

Mike

Your product costs are twice what they should be.

Your product costs are twice what they should be. That’s right. Twice.

Your product costs are twice what they should be. That’s right. Twice.

You don’t believe me. But why? Here’s why:

If 50% cost reduction is possible, that would mean you’ve left a whole shitpot of money on the table year-on-year and that would be embarrassing. But for that kind of money don’t you think you could work through it?

If 50% cost reduction is possible, a successful company like yours would have already done it. No. In fact, it’s your success that’s in the way. It’s your success that’s kept you from looking critically at your product costs. It’s your success that’s allowed you to avoid the hard work of helping the design engineering community change its thinking. But for that kind of money don’t you think you could work through it?

Even if you don’t believe 50% cost reduction is possible, for that kind of money don’t you think it’s worth a try?

A Unifying Theory for Manufacturing?

The notion of a unifying theory is tantalizing – one idea that cuts across everything. Though there isn’t one in manufacturing, I think there’s something close: Design simplification through part count reduction. It cuts across everything – across-the-board simplification. It makes everything better. Take a look how even HR is simplified.

The notion of a unifying theory is tantalizing – one idea that cuts across everything. Though there isn’t one in manufacturing, I think there’s something close: Design simplification through part count reduction. It cuts across everything – across-the-board simplification. It makes everything better. Take a look how even HR is simplified.

HR takes care of the people side of the business and fewer parts means fewer people – fewer manufacturing people to make the product, fewer people to maintain smaller factories, fewer people to maintain fewer machine tools, fewer resources to move fewer parts, fewer folks to develop and manage fewer suppliers, fewer quality professionals to check the fewer parts and create fewer quality plans, fewer people to create manufacturing documentation, fewer coordinators to process fewer engineering changes, fewer RMA technicians to handle fewer returned parts, fewer field service technicians to service more reliable products, fewer design engineers to design fewer parts, few reliability engineers to test fewer parts, fewer accountants to account for fewer line items, fewer managers to manage fewer people.

Before I catch hell for the fewer-people-across-the-board language, product simplification is not about reducing people. (Fewer, fewer, fewer was just a good way to make a point.) In fact, design simplification is a growth strategy – more output with the people you have, which creates a lower cost structure, more profits, and new hires.

A unifying theory? Really? Product simplification?

Your products fundamentally shape your organization. Don’t believe me? Take a look at your businesses – you’ll see your product families in your org structure. Take look at your teams – you’ll see your BOM structure in your org structure. Simplify your product to simplify your company across-the-board. Strange, but true. Give it a try. I dare you.

2010 – Mike’s year in review

I looked back at 2010 and put together the list of things I shipped. (I got the idea from Seth Godin.) I made the list for me, to make sure I took some time to feel good about me and my work. I do.

I looked back at 2010 and put together the list of things I shipped. (I got the idea from Seth Godin.) I made the list for me, to make sure I took some time to feel good about me and my work. I do.

I want to share the list with you (because I’m proud of it). So here it is:

65 posts (goal was 52)

4 articles –

- Cured Offshoring (Machine Design)

- Did Modular Design (Mechanical Engineering Magazine)

- Controlled Controller Design (Design2Part)

- Went Back to Basics with DFMA (Knovel)

Workshop on DFMA Deployment

Keynote presentation DFMA Forum

Started a LinkedIn working group on Systematic DFMA Deployment

Pretended to be a country

Wrote an obituary for Imagination

Sought out Vacation’s killer

Put out a warrant on Dumb-Asses

Wrote about balsamic vinaigrette

Looked into the DoD’s affordability eyeball

Told Secretary of Defense Gates how to save $50 billion (He hasn’t returned my calls.)

I hope you had a good year as well. Mike

WHY, WHAT, HOW, and new thinking for the engineering community.

Sometimes we engineers know the answer before the question, sometimes we know the question’s wrong before it’s asked, and sometimes we’re just plain pig-headed. And if we band together, there’s no hope of changing how things are done. None. So, how to bring new thinking to the engineering community? In three words: WHAT, WHY, HOW.

Sometimes we engineers know the answer before the question, sometimes we know the question’s wrong before it’s asked, and sometimes we’re just plain pig-headed. And if we band together, there’s no hope of changing how things are done. None. So, how to bring new thinking to the engineering community? In three words: WHAT, WHY, HOW.

WHY – Don’t start with WHAT. If you do, we’ll shut down. You don’t know the answer, we do. And you should let us tell you. Start with WHY. Give us the context, give us the problem, give us the business fundamentals, give us the WHY. Let us ask questions. Let us probe. Let us understand it from all our angles. Don’t bother moving on. You can’t. We need to kick the tires to make sure we understand WHY. (It does not matter if you understand WHY. We need understand it for ourselves, in our framework, so we can come up with a solution.)

WHAT – For God’s sake don’t ask HOW – it’s too soon. If you do, we’ll shut down. You don’t know the answer, we do. And, if you know what’s good for you, you should let us tell you. It’s WHAT time. Share your WHAT, give us your rationale, explain how your WHAT follows logically from your WHY, then let us ask questions. We’ll probe like hell and deconstruct your WHY-WHAT mapping and come up with our own, one that makes sense to us, one that fits our framework. (Don’t worry, off-line we’ll test the validity of our framework, though we won’t tell you we’re doing it.) We’ll tell you when our WHY-WHAT map holds water.

HOW – Don’t ask us WHEN! Why are you in such a hurry to do it wrong?! And for sanity’s sake, don’t share your HOW. You’re out of your element. You’ve got no right. Your HOW is not welcome here. HOW is our domain – exclusively. ASK US HOW. Listen. Ask us to explain our WHAT-HOW mapping. Let us come up with nothing (that’s best). Let us struggle. Probe on our map, push on it, come up with your own, one that fits your framework. Then, and only then, share how your HOW fits (or doesn’t) with ours. Let us compare our mapping with yours. Let us probe, let us question, let us contrast. (You’ve already succeeded because we no longer see ours versus yours, we simply see multiple HOWs for consideration.) We’ll come up with new HOWs, hybrid HOWs, all sorts of HOWs and give you the strengths and weaknesses of each. And if your HOW is best we’ll recommend it, though we won’t see it as yours because, thankfully, it has become ours. And we’ll move heaven and earth to make it happen. Engineering has new thinking.

Whether it’s my favorite new thinking (product simplification) or any other, the WHY, WHAT, HOW process works. It works because it’s respectful of our logic, of our nature. It fits us.

Though not as powerful a real Vulcan mind meld, WHY, WHAT, HOW is strong enough to carry the day.

I don’t know the question, but the answer is jobs.

Some sobering facts: (figure and facts from Matt Slaughter)

Some sobering facts: (figure and facts from Matt Slaughter)

- During the Great Recession, US job loss (peak to trough) was 8.4 million payroll jobs were lost (6.1%) and 8.5 million private-sector jobs (7.3%).

- In Sept. 2010 there were 108 million U.S. private-sector payroll jobs, about the same as in March 1999.

- It took 48 months to regain the lost 2.0% of jobs in the 2001 recession. At that rate, the U.S. would again reach 12/07 total payroll jobs around January 2020.

The US has a big problem. And I sure as hell hope we are willing do the hard work and make the hard sacrifices to turn things around.

To me it’s all about jobs. To create jobs, real jobs, the US has got to become a more affordable place to invent, design, and manufacture products. Certainly modified tax policies will help and so will trade agreements to make it easier for smaller companies to export products. But those will take too long. We need something now.

To start, we need affordability through productivity. But not the traditional making stuff productivity, we need inventing and designing productivity.

Here’s the recipe: Invent technology in-country, design and develop desirable products in-country (products that offer real value, products that do something different, products that folks want to buy), make the products in-country, and sell them outside the country. It’s that straightforward.

To me invention/innovation is all about solving technical problems. Solving them more productively creates much needed invention/innovation productivity. The result: more affordable invention/innovation.

To me design productivity is all about reducing product complexity through part count reduction. For the same engineering hours, there are few things to design, fewer things to analyze, fewer to transition to manufacturing. The result: more affordable design.

Though important, we can’t wait for new legislation and trade agreements. To make ourselves more affordable we need to increase productivity of our invention/innovation and design engines while we work on the longer term stuff.

If you’re an engineering leader who wants more about invention/innovation and or design productivity, send me an email at

and use the subject line to let me know which you’re interested in. (Your contact information will remain confidential and won’t be shared with anyone. Ever.)

Together we can turn around the country’s economy.

I see dead people.

Seeing things as they are takes skill, but doing something about it takes courage. Want an example? Check out movie The Sixth Sense directed by M. Night Shyamalan.

Seeing things as they are takes skill, but doing something about it takes courage. Want an example? Check out movie The Sixth Sense directed by M. Night Shyamalan.

At the start of the film Dr. Malcolm Crowe, esteemed child psychologist, returns home with his wife to find his former patient, Vincent Grey, waiting for him. Grey accuses Crowe of failing him and shoots Crowe in the lower abdomen, then shoots himself.

Cut to a scene three months later where Crowe councils Cole Sear, a troubled, isolated nine year old. Over time, Crowe gains the boy’s trust. The boy ultimately confides in Crow telling him he “Sees dead people that walk around like regular people.” (Talk about seeing things as they are.) Later in the film the boy confides in his mother telling her what he sees. Understandably, his mother does not believe him. But imagine his pain when, after sharing his disturbing reality, his only parent does not support him. (And we get upset when co-workers don’t support our somewhat off-axis realities.) And imagine his courage to move forward.

It takes level 5 courage for him to talk about such a disturbing reality, but Cole Sear is up to the challenge. He so badly wants to change his situation, to shape his future, he does what it takes. Not just talk, but actions. He defines his new future and defines the path to get there. He defines his fears and decides to work through them to create his new future where he is no longer afraid of the dead who seek him out. He changes his go-forward behavior. Instead of hiding, he talks with the dead, understands what they want from him, and helps them. He walks the path.

Ultimately he creates a future that works for him. He convinces his mom that his reality is real; she believes him and supports him and his reality. (That’s what we all want, isn’t it?) His relationships with the dead are non-confrontational and grounded in mutual respect. His stress level is back to mortal levels. His reality is real to people he cares about. But Cole Sear is not done yet.

***** SPOILER ALERT – IF YOU HAVE NOT SEEN THE SIXTH SENSE, READ NO FURTHER ****

In Shyamalan’s classic finish-with-a-twist style, Cole Sear, the scared nine year old boy with his bizarre reality, masterfully convinces his psychologist that his I see dead people reality is real and convinces the psychologist that he’s dead. All along, when the psychologist thought he was helping the boy see things as they are, the boy was helping the psychologist. The little boy who saw dead people convinced the dead psychologist that his seemingly bizarre reality was real.

As Cole demonstrated, seeing things for what they are and doing something about can make a difference in someone’s life.

Define the future, walk the path.

If you want to shape what will be, define the future.

If you want to shape what will be, define the future.

a

If you want to know how to get there, define the path.

a

If you want to know what’s in the way, define your fears.

a

If you want to overcome your fears, walk the path.

a

If it doesn’t work, repeat.

Our fear is limiting DoD’s Affordability Quest

The DoD wants to save money, but they can’t do it alone. But can they possibly succeed? Do they have fighting a chance? Can they get it done? Wrong pronouns.

The DoD wants to save money, but they can’t do it alone. But can they possibly succeed? Do they have fighting a chance? Can they get it done? Wrong pronouns.

Can we possibly succeed?

Do we have a fighting chance?

Can we get it done?

In difficult times it’s easy to be critical of others, to make excuses, to look outside. (They, they, they.) In difficult times it’s hard find the level 5 courage to be critical ourselves, to take responsibility, to look inside. (We, we, we.) But we must look inside because that’s where the answer is. We know our work best; we’re the only ones who can reinvent our work; we’re the ones who can save money; we’re responsible.

Changing our actions, our work, is scary, but that’s what the DoD is asking for; we must overcome our fear. But to overcome it we must acknowledge it, see it as it is, and work through it.

Here’s the DoD’s challenge: “Contractors – provide us more affordable systems.” There are two ways we can respond.

The fear-based response (the they response): The DoD won’t accept the changes. In fact, they’ve never liked change. They’ll say no to any changes. They always have.

The seeing things as they are response (the we response): We must try, since not trying is the only way to guarantee failure. Things are different now. Change is acceptable. However, the facts are we don’t know what changes to propose, we don’t know what creates cost, and we don’t know how to design low cost, low complexity systems. We were never taught. We need to develop our capability if we’re to be successful.

The they response: Their MIL specs dictate the design and they won’t budge on them. They’ll say no to any changes. They always have.

The we response: We must try, since not trying is the only way to guarantee failure. Things are different now. Change is acceptable. However, the facts are we don’t know why we designed it that way, we don’t know all that much about the design, we don’t know what creates cost, and we don’t know how to design low cost, low complexity systems. We were never taught. We need to develop our capability if we’re to be successful.

The they response: All they care about is performance. They are driving the complexity. And when push comes to shove, they don’t care about cost. They’ll say no to any changes. They always have.

The we response: We must try, since not trying is the only way to guarantee failure. Things are different now. Change is acceptable. However, the facts are we don’t know what truly controls performance, we don’t know what we can change, we don’t know the sensitivities, we don’t know what creates cost, and we don’t know how to design low cost, low complexity systems. We were never taught. We need to develop our capability if we’re to be successful.

The DoD has courageously told us they want to overcome their fear. Let’s follow their lead and overcome ours. It will be good for everyone.

DoD’s Affordability Eyeball

The DoD wants to do the right thing. Secretary Gates wants to save $20B per year over the next five years and he’s tasked Dr. Ash Carter to get it done. In Carter’s September 14th memo titled: “Better Buying Power: Guidance for Obtaining Greater Efficiency and Productivity in Defense Spending” he writes strongly:

The DoD wants to do the right thing. Secretary Gates wants to save $20B per year over the next five years and he’s tasked Dr. Ash Carter to get it done. In Carter’s September 14th memo titled: “Better Buying Power: Guidance for Obtaining Greater Efficiency and Productivity in Defense Spending” he writes strongly:

…we have a continuing responsibility to procure the critical goods and services our forces need in the years ahead, but we will not have ever-increasing budgets to pay for them.

And, we must

DO MORE WITHOUT MORE.

I like it.

Of the DoD’s $700B yearly spend, $200B is spent on weapons, electronics, fuel, facilities, etc. and $200B on services. Carter lays out themes to reduce both flavors. On services, he plainly states that the DoD must put in place systems and processes. They’re largely missing. On weapons, electronics, etc., he lays out some good themes: rationalization of the portfolio, economical product rates, shorter program timelines, adjusted progress payments, and promotion of competition. I like those. However, his Affordability Mandate misses the mark.

Though his Affordability Mandate is the right idea, it’s steeped in the wrong mindset, steeped in emotional constraints that will limit success. Take a look at his language. He will require an affordability target at program start (Milestone A)

to be treated like a Key Performance Parameter (KPP) such as speed or power – a design parameter not to be sacrificed or comprised without my specific authority.

Implicit in his language is an assumption that performance will decrease with decreasing cost. More than that, he expects to approve cost reductions that actually sacrifice performance. (Only he can approve those.) Sadly, he’s been conditioned to believe it’s impossible to increase performance while decreasing cost. And because he does not believe it, he won’t ask for it, nor get it. I’m sure he’d be pissed if he knew the real deal.

The reality: The stuff he buys is radically over-designed, radically over-complex, and radically cost-bloated. Even without fancy engineering, significant cost reductions are possible. Figure out where the cost is and design it out. And the lower cost, lower complexity designs will work better (fewer things to break and fewer things to hose up in manufacturing). Couple that with strong engineering and improved analytical tools and cost reductions of 50% are likely. (Oh yes, and a nice side benefit of improved performance). That’s right, 50% cost reduction.

Look again at his language. At Milestone B, when a system’s detailed design is begun,

I will require a presentation of a systems engineering tradeoff analysis showing how cost varies as the major design parameters and time to complete are varied. This analysis would allow decisions to be made about how the system could be made less expensive without the loss of important capability.

Even after Milestone A’s batch of sacrificed of capability, at Milestone B he still expects to trade off more capability (albeit the lesser important kind) for cost reduction. Wrong mindset. At Milestone B, when engineers better understand their designs, he should expect another step function increase in performance and another step function decrease of cost. But, since he’s been conditioned to believe otherwise, he won’t ask for it. He’ll be pissed when he realizes what he’s leaving on the table.

For generations, DoD has asked contractors to improve performance without the least consideration of cost. Guess what they got? Exactly what they asked for – ultra-high performance with ultra-ultra-high cost. It’s a target rich environment. And, sadly, DoD has conditioned itself to believe increased performance must come with increased cost.

Carter is a sharp guy. No doubt. Anyone smart enough to reduce nuclear weapons has my admiration. (Thanks, Ash, for that work.) And if he’s smart enough to figure out the missile thing, he’s smart enough to figure out his contractors can increase performance and radically reduces costs at the same time. Just a matter of time.

There are two ways it could go: He could tell contractors how to do it or they could show him how it’s done. I know which one will feel better, but which will be better for business?

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski