A Healthy Dissatisfaction With Success

They say job satisfaction is important for productivity and quality. The thinking goes something like this: A happy worker is a productive one, and a satisfied worker does good work. This may be true, but it’s not always the best way.

They say job satisfaction is important for productivity and quality. The thinking goes something like this: A happy worker is a productive one, and a satisfied worker does good work. This may be true, but it’s not always the best way.

I think we may be better served by a therapeutic dose of job dissatisfaction. Though there are many strains of job satisfaction, the most beneficial one spawns from a healthy dissatisfaction with our success. The tell-tale symptom of dissatisfaction is loneliness, and the invasive bacterium is misunderstanding. When the disease is progressing well, people feel lonely because they’re misunderstood.

Recycled ideas are well understood; company dogma is well understood; ideas that have created success are well understood. In order to be misunderstood, there must be new ideas, ideas that are different. Different ideas don’t fit existing diagnoses and create misunderstanding which festers into loneliness. In contrast, when groupthink is the disease there is no loneliness because there are no new ideas.

For those that believe last year’s ideas are good enough, different ideas are not to be celebrated. But for those that believe otherwise, new ideas are vital, different is to be celebrated, and loneliness is an important precursor to innovation.

Yes, new ideas can grow misunderstanding, but misunderstanding on its own cannot grow loneliness. Loneliness is fueled by caring, and without it the helpful strain of loneliness cannot grow. Caring for a better future, caring for company longevity, caring for a better way – each can create the conditions for loneliness to grow.

When loneliness is the symptom, the prognosis is good. The loneliness means the organization has new ideas; it means the ideas are so good people are willing to endure personal suffering to make them a reality; and, most importantly, it means people care deeply about the company and its long term success.

I urge you to keep your eye out for the markers that define the helpful strain of loneliness. And when you spot it, I hope you will care enough to dig in a little. I urge you think of this loneliness as the genes of a potentially game-changing idea. When ideas are powerful enough to grow loneliness, they’re powerful enough to move from evolutionary into revolutionary.

How long will it take?

How long will it take? The short answer – same as last time. How long do we want it to take? That’s a different question altogether.

How long will it take? The short answer – same as last time. How long do we want it to take? That’s a different question altogether.

If the last project took a year, so will the next one. Even if you want it to take six months, it will take a year. Unless, there’s a good reason it will be different. (And no, the simple fact you want it to take six months is not a good enough reason in itself.)

Some good reasons it will take longer than last time: more work, more newness, less reuse, more risk, and fewer resources. Some good reasons why it will go faster: less work, less newness, more reuse, less risk, more resources. Seems pretty tight and buttoned-up, but things aren’t that straight forward.

With resources, the core resources are usually under control. It’s the shared resources that are the problem. With resources under their control (core resources) project teams typically do a good job – assign dedicated resources and get out of the way. Shared resources are named that way because they support multiple projects, and this is the problem. Shared resources create coupling among projects, and when one project runs long, resource backlogs ripple through the other projects. And it gets worse. The projects backlogged by the initial ripple splash back and reflect ripples back at each other. Understand the shared resources, and you understand a fundamental dynamic of all your projects.

Plain and simple – work content governs project timelines. And going forward I propose we never again ask “How long will it take?” and instead ask “How is the work content different than last time?” To estimate how long it will take, set up a short face-to-face meeting with the person who did it last time, and ask them how long it will take. Write it down, because that’s the best estimate of how long it will take.

It may be the best estimate, but it may not be a good one. The problem is uncertainty around newness. Two important questions to calibrate uncertainty: 1) How big of a stretch are you asking for? and 2) How much do you know about how you’ll get there? The first question drives focus, but it’s not always a good predictor of uncertainty. Even seemingly small stretches can create huge problems. (A project that requires a 0.01% increase in the speed of light will be a long one.) What matters is if you can get there.

To start, use your best judgment to estimate the uncertainty, but as quickly as you can, put together a rude and crude experimental plan to reduce it. As fast as you can execute the experimental plan, and let the test results tell you if you can get there. If you can’t get there on the bench, you can’t get there, and you should work on a different project until you can.

The best way to understand how long a project will take is to understand the work content. And the most important work content to understand is the new work content. Choose several of your best people and ask them to run fast and focused experiments around the newness. Then, instead of asking them how long it will take, look at the test results and decide for yourself.

Drag Racing Behavior

Our productivity-by-the-minute culture is killing us.

Our productivity-by-the-minute culture is killing us.

In business speed is king, and with it comes our short-sighted drag racing behavior. As we pull to the starting light our big engines shake and rumble, our pipes shoot flames, and our tires smoke. We stomp the throttle, accelerate to mach 1, kill the engine, and throw the chute. A quarter mile covered in record time, and champagne celebration.

But, because the pace was beyond sustainable, we can’t race again until the damage is repaired. Because it ran too hot the pit crew must pull the engine, because the torque was so outrageous the transmission must be swapped, and because the vibrations were so severe the frame must be checked for metal fatigue. But this is just another opportunity for more racing.

We externalize the setup, design the process for quick changeover, reduce waste, and focus on the vital few. No matter the pit crew doesn’t get sleep, or their families miss them. Engine swapped in record time, and obligatory celebration.

Sure, going fast is good. But business can’t be a series of back-to-back sprints. Plain and simple – people cannot sprint every day, all day. Business should be thought of as a marathon. A marathon run at a respectable pace, but a pace we’ve trained for, a pace we can sustain. With a torn hamstring the fastest sprinter makes no forward progress, and even the slowest marathoner is faster.

Sprint, yes, but only when it makes sense. Sprint, yes, but provide recovery time. Sprint, yes, but not if it will do personal harm.

Increasing speed is directionally correct, but our time horizon is too short. Instead of optimizing over a six second quarter mile, we should optimize for a marathon.

In our chase for speed’s euphoric high, our drug of choice is efficiency. Like speed, efficiency is good. But, just as speed’s time horizon is too short, efficiency’s scale of optimization is too small. We optimize locally and the net result is global sub-optimization. This is clearly an artifact of what we measure. Clearly, we must measure differently.

Every day we chase the dopamine high of efficiency, but ignore the mind-blowing power of effectiveness. If you sprint day after day, you may be efficient, but you’re definitely ineffective. Sprint every day for a month, sleep four hours a night, and spend six weeks away from your family. Are you really in a good position to make a make-or-break decision? How can you possibly be effective? I wish Finance knew how to measure effectiveness as well as it does efficiency.

As a company leader, stop sprinting. As a company leader, stop optimizing locally. As a company leader, stop focusing on efficiency. As a company leader, demonstrate and reward effectiveness. As a company leader, go home and spend time with your family.

Hearts Before Minds

We often forget, but regardless of industry, technology, product, or service, it’s a battle for hearts and minds.

We often forget, but regardless of industry, technology, product, or service, it’s a battle for hearts and minds.

The building blocks of business are processes, machines, software, and computers, but people are the underpinning. The building blocks respond in a repeatable way – same input, same output – and without judgment. People, however, not so much.

People respond differently depending on delivery – even small nuances can alter the response, and when hot buttons are pushed responses can be highly nonlinear. One day to the next, people’s responses to similar input can be markedly different. Yet we forget people are not like software or machines, and we go about our work with expectations people will respond with highly rational, highly linear, A-then-B logic. But in a battle between rational and emotional, it’s emotional by a landslide.

Thankfully, we’re not just cogs in the machine. But for the machine to run, it’s imperative to win the hearts and minds. (I feel a little silly writing this because it’s so fundamental, but it needs to be written.) And it’s hearts then minds. The heart is won by emotion, and once the emotional connection is made, the heart tells the mind to look at the situation and construct logic to fit. The heart clears the path so the mind can in good conscience come along for the ride.

Hearts are best won face-to-face, but, unfortunately today’s default mode is PowerPoint-to-face. We don’t have to like it, but it’s here to stay. And so, we must learn to win hearts, to make an emotional connection, to tell stories with PowerPoint.

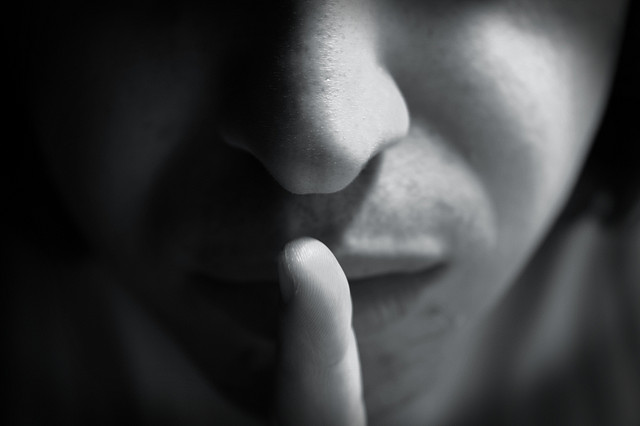

To tell a story with PowerPoint, we must bring ourselves to the forefront and send PowerPoint to the back. To prevent ourselves from hiding behind our slides, take the words off and replace them with a single, large image – instead of a complex word-stuffed jumble, think framed artwork. While their faces look at the picture, tell their hearts a story. Eliminate words from the slides and the story emerges.

[There’s still a place for words, but limit yourself to three words per slide, and make them big – 60 point font. And keep it under ten slides. More than that and you haven’t distilled the story in your head.]

Whatever business you’re in, you’re in the people business. Win hearts and minds follow. And so do profits.

There Are No Best Practices

That’s a best practice. Look, there’s another one. We need a best practice. What’s the best practice? Let’s standardize on the best practice. Arrrgh. Enough, already, with best practices.

That’s a best practice. Look, there’s another one. We need a best practice. What’s the best practice? Let’s standardize on the best practice. Arrrgh. Enough, already, with best practices.

There are no best practices, only actions that have worked for others in other situations. Yet we feverishly seek them out, apply them out of context, and expect they’ll solve a problem unrelated to their heritage.

To me, the right practices are today’s practices. They’re the base camp from which to start a journey toward new ones. To create the next evolution of today’s practices, for new practices to emerge, a destination must be defined. This destination is dictated by problems with what we do today. Ultimately, at the highest level, problems with our practices are spawned by gaps, shortfalls, or problems in meeting company objectives. Define the shortfall – 15% increase in profits – and emergent practices naturally diffuse to the surface.

There are two choices: choose someone else’s best practices and twist, prune, and bend them to fit, or define the incremental functionality you’d like to create and lay out the activities (practices) to make it happen. Either way, the key is starting with the problem.

The important part – the right practices, the new activities, the novel work, whatever you call it, emerges from the need.

It’s a problem hierarchy, a problem flow-down. The company starts by declaring a problem – profits must increase by 15% – and the drill-down occurs until a set of new action (new behaviors, new processes, new activities) is defined that solves the low level problems. And when the low level problems are solved, the benefits avalanche to satisfy the declared problem – profits increased by 15%.

It’s all about clarity — clearly define the starting point, clearly define the destination, and express the gaps in a single page, picture-based problem statements. With this type of problem definition, you can put your hand over your mouth, with the other hand point to the picture, and everyone understands it the same way. No words, just understanding.

And once everyone understands things clearly, the right next steps (new practices) emerge.

Error Doesn’t Matter, Trial Does

If you want to learn, to really learn, experiment.

If you want to learn, to really learn, experiment.

But I’m not talking about elaborate experiments; I’m talking about crude ones. Not simple ones, crude ones.

We were taught the best experiments maximize learning, but that’s dead wrong. The best experiments are fast, and the best way to be fast is to minimize the investment.

In the name of speed, don’t maximize learning, minimize the investment.

Let’s get right to it. One of the best tricks to minimize investment is to minimize learning – learning per experiment, that is. Define learning narrowly, design the minimum experiment, and run the trial. Learning per trial is low, but learning per month skyrockets because the number of trials per month skyrockets. But it gets better. There’s an interesting learning exponential at work. The first trial informs the second which shapes the third. But instead of three units of learning, it’s cubic. And minimizing learning doesn’t just half the time to run a trial, it reduces it by 100 or more. It’s earning to the hundredth power.

Another way to minimize investment is to minimize resolution. Don’t think nanometers, think thumbs up, thumbs down. Design the trial so the coarsest measuring stick gives an immediate and unambiguous response. There’s no investment in expensive measurement gear and no time invested in interpretation of results. Think sledgehammer to the forehead.

A third way to minimize investment is to evaluate relative differences. The best example is the simple, yet powerful, A-B test . Run two configurations, decide which is better, and run quickly in the direction of goodness. No need to fret about how much better, just sprint toward it. The same goes for trial 1 versus trial 2 comparisons. Here’s the tricky algorithm: If trial 2 is better, do more of that. And the good news applies here too – the learning exponential is still in play. Better to the hundredth power, in record time.

I don’t care what norms you have to bend or what rules you have to break. If you do one thing, run more trials.

But don’t take my word for it. Dr. Seuss had it right:

And I would run them in a boat!

And I would run them with a goat…

And I will run them in the rain.

And in the dark. And on a train.

And in a car. And in a tree.

They are so good so good you see!

Innovation Eats Itself

We all want more innovation, though sometimes we’re not sure why. Turns out, the why important.

We all want more innovation, though sometimes we’re not sure why. Turns out, the why important.

We want to be more innovative. That’s a good vision statement, but it’s not actionable. There are lots of ways to be innovative, and it’s vitally important to figure out the best flavor. Why do you want to be more innovative?

We want to be more innovative to grow sales. Okay, that’s a step closer, but not actionable. There are many ways to grow sales. For example, the best and fastest way to sell more units is to reduce the price by half. Is that what you want? Why do you want to grow sales?

We want to be more innovative to grow sales so we can grow profits. Closer than ever, but we’ve got to dig in and create a plan.

First, let’s begin with the end in mind. We’ve got to decide how we’ll judge success. How much do we want to grow profits? Double, you say? Good – that’s clear and measurable. I like it. When will we double profits? In four years, you say? Another good answer – clear and measureable. How much money can we spend to hit the goal? $5 million over four years. And does that incremental spending count against the profit target? Yes, year five must double this year’s profits plus $5 million.

Now that we know the what, let’s put together the how. Let’s start with geography. Will we focus on increasing profits in our existing first world markets? Will we build out our fledgling developing markets? Will we create new third world markets? Each market has different tastes, cultures, languages, infrastructure requirements, and ability to pay. And because of this, each requires markedly different innovations, skill sets, and working relationships. This decision must be made now if we’re to put together the right innovation team and organizational structure.

Now that we’ve decided on geography, will we do product innovation or business model innovation? If we do product innovation, do we want to extend existing product lines, supplement them with new product lines, or replace them altogether with new ones? Based on our geography decision, do we want to improve existing functionality, create new functionality, or reduce cost by 80% of while retaining 80% of existing functionality?

If we want to do business model innovation, that’s big medicine. It will require we throw away some of the stuff that has made us successful. And it will touch almost everyone. If we’re going to take that on, the CEO must take a heavy hand.

For simplicity, I described a straightforward, linear process where the whys are clearly defined and measurable and there’s sequential flow into a step-wise process to define the how. But it practice, there’s nothing simple or linear about the process. At best there’s overwhelming ambiguity around why, what, and when, and at worst, there’s visceral disagreement. And worse, with 0% clarity and an absent definition of success, there are several passionate factions with fully built-out plans that they know will work.

In truth, figuring out what innovation means and making it happen is a clustered-jumbled path where whats inform whys, whys transfigure hows, which, in turn, boomerang back to morph the whats. It’s circular, recursive, and difficult.

Innovation creates things that are novel, useful, and successful. Novel means different, different means change, and change is scary. Useful is contextual – useful to whom and how will they use it? – and requires judgment. (Innovations don’t yet exist, so innovation efforts must move forward on predicted usefulness.) And successful is toughest of all because on top of predicted usefulness sit many other facets of newness that must come together in a predicted way, all of which can be verified only after the fact.

Innovation is a different animal altogether, almost like it eats itself. Just think – the most successful innovations come at the expense of what’s been successful.

Engineering Will Carry the Day

Engineering is more important than manufacturing – without engineering there is nothing to make, and engineering is more important than marketing – without it there is nothing to market.

Engineering is more important than manufacturing – without engineering there is nothing to make, and engineering is more important than marketing – without it there is nothing to market.

If I could choose my competitive advantage, it would be an unreasonably strong engineering team.

Ideas have no value unless they’re morphed into winning products, and that’s what engineering does. Technology has no value unless it’s twisted into killer products. Guess who does that?

We have fully built out methodologies for marketing, finance, and general management, each with all the necessary logic and matching toolsets, and manufacturing has lean. But there is no such thing for engineering. Stress analysis or thermal modeling? Built a prototype or do more thinking? Plastic or aluminum? Use an existing technology or invent a new one? What new technology should be invented? Launch the new product as it stands or improve product robustness? How is product robustness improved? Will the new product meet the specification? How will you know? Will it hit the cost target? Will it be manufacturable? Good luck scripting all that.

A comprehensive, step-by-step program for engineering is not possible.

Lean says process drives process, but that’s not right. The product dictates to the factory, and engineers dictate the product. The factory looks as it does because the product demands it, and the product looks as it does because engineers said so.

I’d rather have a product that is difficult to make but works great rather than one that jumps together but works poorly.

And what of innovation? The rhetoric says everyone innovates, but that’s just a nice story that helps everyone feel good. Some innovations are more equal than others. The most important innovations create the killer products, and the most important innovators are the ones that create them – the engineers.

Engineering as a cost center is a race to the bottom; engineering as a market creator will set you free.

The only question: How are you going to create a magical engineering team that changes the game?

The Middle Term Enigma

Short term is getting shorter, and long term is a thing of the past.

Short term is getting shorter, and long term is a thing of the past.

We want it now; no time for new; it’s instant gratification for us, but only if it doesn’t take too long.

A short time horizon drives minimization. Minimize waste; reduce labor hours; eliminate features and functions; drop the labor rate; cut headcount; skim off the top. Short term minimizes what is.

Short term works in the short term, but in the long term it’s asymptotic. Short term hits the wall when the effort to minimize overwhelms the benefit. And at this cusp, all that’s left is an emaciated shadow of what was. Then what? The natural extrapolation of minimization is scary – plain and simple, it’s a race to the bottom.

Where short term creates minimization, long term creates maximization. But, today, long term has mostly negative connotations – expensive, lots of resources, high risk, and low probability of success. At the personal level long term, is defined as a timeframe longer than we’re measured or longer than we’ll be in the role.

But, thankfully, there comes a time in our lives when it’s important for personal reasons to inject long term antibodies into the short term disease. But what to inject?

Before what, you must figure out why you want to swim against the current of minimization. If it’s money, don’t bother. Your why must have staying power, and money’s is too short. Some examples of whys that can endure: you want a personal challenge; you want to help society; your ego; you want to teach; or you want to help the universe hold off entropy for a while. But the best why is the work itself – where the work is inherently important to you.

With your why freshly tattooed on your shoulder, choose your what. It will be difficult to choose, but that’s the way it is with yet-to-be whats. (Here’s a rule: with whats that don’t yet exist, you don’t know they’re the right one until after you build them.) So just choose, and build.

Here are some words to describe worthwhile yet-to-be whats: barely believable, almost heretical, borderline silly, and on-the-edge, but not over it. These are the ones worth building.

Building (prototyping) can be expensive, but that’s not the type of building I’m talking about. Building is expensive when we try to get the most out of a prototype. Instead, to quickly and efficiently investigate, the mantra is: minimize the cost of the build. (The irony is not lost on me.) You’ll get less from the prototype, but not much. And most importantly, resource consumption will be ultra small – think under the radar. Take small, inexpensive bites; cover lots of ground; and build yourself toward the right what.

Working prototypes, even crude ones, are priceless because they make it real. And it’s the series of low cost, zig-zagging, leap-frogging prototypes that make up the valuable war chest needed to finance the long campaign against minimization.

Short term versus long term is a balancing act. Your prototype must pull well forward into the long term so, when the ether of minimization pulls back, it all slides back to the middle term, where it belongs.

How Engineers Create New Markets

When engineers see a big opportunity, we want desperately to move the company in the direction of our thinking, but find it difficult to change the behavior of others. Our method of choice is usually a full frontal assault, explaining to anyone that will listen the opportunity as we understand it. Our approach is straightforward and ineffective. Our descriptions are long, convoluted, complicated, we use confusing technical language all our own, and omit much needed context that we expect others should know. The result – no one understands what we’re talking about and we don’t get the behavior we’re looking for (immediate company realignment with what we know to be true). Then, we get frustrated and shut down – opportunity lost.

When engineers see a big opportunity, we want desperately to move the company in the direction of our thinking, but find it difficult to change the behavior of others. Our method of choice is usually a full frontal assault, explaining to anyone that will listen the opportunity as we understand it. Our approach is straightforward and ineffective. Our descriptions are long, convoluted, complicated, we use confusing technical language all our own, and omit much needed context that we expect others should know. The result – no one understands what we’re talking about and we don’t get the behavior we’re looking for (immediate company realignment with what we know to be true). Then, we get frustrated and shut down – opportunity lost.

To change the behavior of others, we must first change our own. As engineers we see problems which, when solved, result in opportunity. And if we’re to be successful, we must go back to the problem domain and set things straight. Here’s a sequence of new behaviors we as engineers can take to improve our chances of changing the behavior of others:

Step 1. Create a block diagram of the physical system using simple nouns (blocks) and verbs (arrows). Blue arrows are good (useful actions) and red arrows are bad (harmful actions). Here’s a link to a PowerPoint file with a live template to create your own.

Step 2. Reduce the system block diagram down to its essence to create a distilled block diagram of the problem, showing only the system elements (blocks) with the problem (red arrow).For a live template, see the second page of the linked file. [Note – if there are two red arrows in the system block diagram, there are two problems which must be solved separately. Break them into two and solve the first one first. For an example, see page three of the linked file.]

Step 3. Create a hand sketch, or cartoon, showing the two system elements (blocks) of the distilled block diagram from step 2. Zoom in so only the two elements are visible, and denote where they touch (where the problem is), in red. For an example, see page four of the linked file.

Step 4. Now that you understand the real problem, use Google to learn how others have solved it.

Step 5. Choose one of Google’s most promising solutions and prototype it. (Don’t ask anyone, just build it.)

Step 6. Show the results to your engineering friends. If the problem is solved, it’s now clear how the opportunity can be realized. (There’s a big difference between a crazy engineer with a radically new market opportunity and a crazy engineer with test results demonstrating a new technology that will create a whole new market.)

Step 7. If the problem is not solved, or you solved the wrong problem, go back to step 1 and refine the problem

With step 1 you’ll find you really don’t understand the physical system, you don’t know which elements of the system have the problem, and you can’t figure out what the problem is. (I’ve created complicated system block diagrams only to realize there was no problem.)

With step 2, you’ll continue to struggle to zoom in on the problem. And, likely, as you try to define the problem, you’ll go back to step 1 and refine the system block diagram. Then, you’ll struggle to distill the problem down to two blocks (system elements). You’ll want to retain the complexity (many blocks) because you still don’t understand the real problem.

If you’ve done step 2 correctly, step 3 is easy, though you’ll still want to complicate the cartoon (too many system elements) and you won’t zoom in close enough.

Step 4 is powerful. Google can quickly and inexpensively help you see how the world has already solved your problem.

Step 5 is more powerful still.

Step 6 shows Marketing what the future product will do so they can figure out how to create the new market.

Step 7 is how problems are really solved and opportunities actually realized.

When you solve the real problem, you create real opportunities.

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski