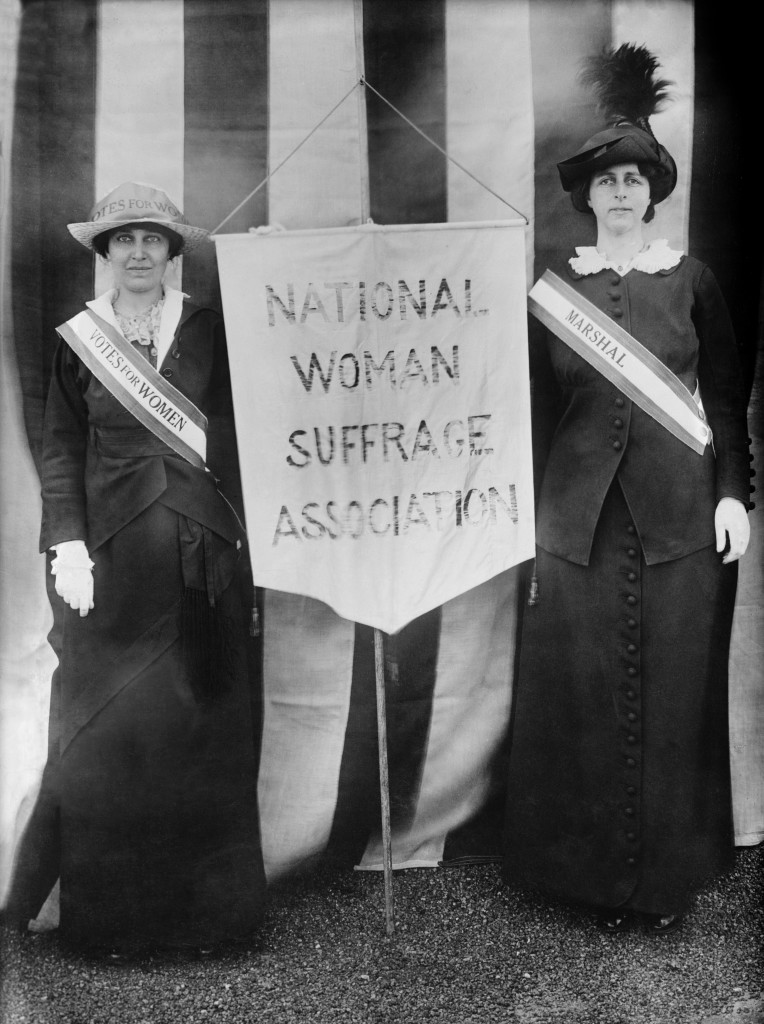

To make a difference, add energy.

If you want to make a difference, you’ve got to add energy. And the more you can add the bigger difference you can make.

If you want to make a difference, you’ve got to add energy. And the more you can add the bigger difference you can make.

Doing new is difficult and demands (and deserves) all the energy you can muster. Often it feels you’re the only one pushing in the right direction while everyone else is vehemently pushing the other way. But stay true and stand tall. This is not an indication things are going badly, this is a sign you’re doing meaningful work. It’s supposed to feel that way. If you’re exhausted, frustrated and sometimes a bit angry, you’re doing it right. If you have a healthy disrespect for the status quo, it’s supposed to feel that way.

Meaningful work has a long time constant and you’ve got to run these meaningful projects like marathons, uphill marathons. Every day you put in your 26 miles at a sustainable pace – no slower, but no faster. This is long, difficult work that doesn’t run by itself, you’ve got to push it like a sled. Every day you’ve got to push. To push every day like this takes a lot of physical strength, but it takes even more mental strength. You’ve got to stay focused on the critical path and push that sled every day. And you need to preserve enough mental energy to effectively ignore the non-critical path sleds. You’ve got to be able to decide which tasks you must get your whole body behind and which tasks you must discount. And you’ve got to preserve enough energy to believe in yourself.

Meaningful work cannot be accomplished by sprinting full speed five days a week. It’s a marathon, and you’ve got to work that way and train that way. Get your rest, get your exercise, eat right, spend time with friends and family, and put your soul into your work.

Choose work that is meaningful and add energy. Add it every day. Add it openly. Add it purposefully. Add it genuinely. Add energy like you’re an aircraft carrier and others will get pulled along by your wake. Add energy like you’re bulldozer and others will get out of your way. Add energy like you’re contagious and others will be infected.

Image credit – anton borzov

If there’s no conflict, there’s no innovation.

With Innovation, things aren’t always what they seem. And the culprit for all this confusion is how she goes about her work. Innovation starts with different, and that’s the source of all the turmoil she creates.

With Innovation, things aren’t always what they seem. And the culprit for all this confusion is how she goes about her work. Innovation starts with different, and that’s the source of all the turmoil she creates.

For the successful company, Innovation demands the company does things that are different from what made it successful. Where the company wants to do more of the same (but done better), Innovation calls it as she sees it and dismisses the behavior as continuous improvement. Innovation is a big fan of continuous improvement, but she’s a bit particular about the difference between doing things that are different and things that are the same.

The clashing of perspectives and the gnashing of teeth is not a bad thing, in fact it’s good. If Innovation simply rolls over when doing the same is rationalized as doing differently, nothing changes and the recipe for success runs out of gas. Said another way, company success is displaced by company failure. When innovation creates conflict over sameness she’s doing the company favor. Though it sometimes gives her a bad name, she’s willing to put up with the attack on her character.

The sacred business model is a mortal enemy of Innovation. Those two have been getting after each other for a long time now, and, thankfully, Innovation is willing to stand tall against the sacred business model. Innovation knows even the most sacred business models have a half-life, and she knows that she must actively dismantle them as everyone else in the company tries to keep them on life support long after they should have passed. Innovation creates things that are different (novel), useful and successful to help the company through the sad process of letting the sacred business model die with dignity. She’s willing to do the difficult work of bringing to life a younger more viral business model, knowing full well she’s creating controversy and turmoil at every turn. Innovation knows the company needs help admitting the business model is tired and old, and she’s willing to do the hard work of putting it out to pasture. She knows there’s a lot of misplaced attachment to the tired business model, but for the sake of the company, she’s willing to put it out of its misery.

For a long time now the company’s products have delivered the same old value in the same old way to the same old customers, and Innovation knows this. And because she knows that’s not sustainable, she makes a stink by creating different and more profitable value to different and more valuable customers. She uses different assumptions, different technologies and different value propositions so the company can see the same old value proposition as just that – old (and tired). Yes, she knows she’s kicking company leaders in the shins when she creates more value than they can imagine, but she’s doing it for the right reasons. Knowing full well people will talk about her behind her back, she’s willing to create the conflict needed to discredit old value proposition and adopt a new one.

Innovation is doing the company a favor when she creates strife, and the should company learn to see that strife not as disagreement and conflict for their own sake, rather as her willingness to do what it takes to help the company survive in an unknown future. Innovation has been around a long time, and she knows the ropes. Over the centuries she’s learned that the same old thing always runs out of steam. And she knows technologies and their business models are evolving faster than ever. Thankfully, she’s willing to do the difficult work of creating new technologies to fuel the future, even as the status quo attacks her character.

Without Innovation’s disruptive personality there would be far less conflict and consternation, but there’d also be far less change, far less growth and far less company longevity. Yes, innovation takes a strong hand and is sometimes too dismissive of what has been successful, but her intentions are good. Yes, her delivery is sometimes too harsh, but she’s trying to make a point and trying to help the company survive.

Keep an eye out for the turmoil and conflict that Innovation creates, and when you see it fan the flames. And when hear the calls of distress of middle managers capsized by her wake of disruption, feel good that Innovation is alive and well doing the hard work to keep the company afloat.

The time to worry is not when Innovation is creating conflict and consternation at every turn; the time to worry is when the telltale signs of her powerful work are missing.

The Top Three Enemies of Innovation – Waiting, Waiting, Waiting

All innovation projects take longer than expected and take more resources than expected. It’s time to change our expectations.

All innovation projects take longer than expected and take more resources than expected. It’s time to change our expectations.

With regard to time and resources, innovation’s biggest enemy is waiting. There. I said it.

There are books and articles that say innovation is too complex to do quickly, but complexity isn’t the culprit. It’s true there’s a lot of uncertainty with innovation, but, uncertainty isn’t the reason it takes as long as it does. Some blame an unhealthy culture for innovation’s long time constant, but that’s not exactly right. Yes, culture matters, but it matters for a very special reason. A culture intolerant of innovation causes a special type of waiting that, once eliminated, lets innovation to spool up to break-neck speeds.

Waiting? Really? Waiting is the secret? Waiting isn’t just the secret, it’s the top three secrets.

In a backward way, our incessant focus on productivity is the root cause for long wait times and, ultimately, the snail’s pace of innovation. Here’s how it goes. Innovation takes a long time so productivity and utilization are vital. (If they’re key for manufacturing productivity they must be key to innovation productivity, right?) Utilization of fixed assets – like prototype fabrication and low volume printed circuit board equipment – is monitored and maximized. The thinking goes – Let’s jam three more projects into the pipeline to get more out of our shared resources. The result is higher utilizations and skyrocketing queue times. It’s like company leaders don’t believe in queuing theory. Like with global warming, the theory is backed by data and you can’t dismiss queuing theory because it’s inconvenient.

One question: If over utilization of shared resources delays each prototype loop by two weeks (creates two weeks of incremental wait time) and you cycle through 10 prototype loops for each innovation project, how many weeks does it delay the innovation project? If you said 20 weeks you’re right, almost. It doesn’t delay just that one project; it delays all the projects that run through the shared resource by 20 weeks. Another question: How much is it worth to speed up all your innovation projects by 20 weeks?

In a second backward way, our incessant drive for productivity blinds us of the negative consequences of waiting. A prototype is created to determine viability of a new technology, and this learning is on the project’s critical path. (When the queue time delays the prototype loop by two weeks, the entire project slips two weeks.) Instead of working to reduce the cycle time of the prototype loop and advance the critical path, our productivity bias makes us work on non-critical path tasks to fill the time. It would be better to stop work altogether and help the company feel the pain of the unnecessarily bloated queue times, but we fill the time with non-critical path work to look busy. The result is activity without progress, and blindness to the reason for the schedule slip – waiting for the over utilized shared resource.

A company culture intolerant of uncertainty causes the third and most destructive flavor of waiting. Where productivity and over utilization reduce the speed of innovation, a culture intolerant of uncertainty stops innovation before it starts. The culture radiates negative energy throughout the labs and blocks all experiments where the results are uncertain. Blocking these experiments blocks the game-changing learning that comes with them, and, in that way, the culture create infinite wait time for the learning needed for innovation. If you don’t start innovation you can never finish. And if you fix this one, you can start.

To reduce wait time, it’s important to treat manufacturing and innovation differently. With manufacturing think efficiency and machine utilization, but with innovation think effectiveness and response time. With manufacturing it’s about following an established recipe in the most productive way; with innovation it’s about creating the new recipe. And that’s a big difference.

If you can learn to see waiting as the enemy of innovation, you can create a sustainable advantage and a sustainable company. It’s time to change expectations around waiting.

Image credit – Pulpolux !!!

The People Business

Things don’t happen on their own, people make them happen.

With all the new communication technologies and collaboration platforms it’s easy to forget that what really matters is people. If people don’t trust each other, even the best collaboration platforms will fall flat, and if they don’t respect each other, they won’t communicate – even with the best technology.

Companies put stock in best practices like they’re the most important things, but they’re not. Because of this unnatural love affair, we’re blinded to the fact people are what make best practices best. People create them, people run them, and people improve them. Without people there can be no best practices, but on the flip-side, people can get along just fine without best practices. (That says something, doesn’t it?) Best practices are fine when processes are transactional, but few processes are 100% transactional to the core, and the most important processes are judgement-based. In a foot race between best practices and good judgement, I’ll take people and their judgment – every day.

Without a forcing function, there can be no progress, and people are the forcing function. To be clear, people aren’t the object of the forcing function, they are the forcing function. When people decide to commit to a cause, the cause becomes a reality. The new reality is a result – a result of people choosing for themselves to invest their emotional energy. People cannot be forced to apply their life force, they must choose for themselves. Even with today’s “accountable to outcomes” culture, the power of personal choice is still carries the day, though sometimes it’s forced underground. When pushed too hard, under the cover of best practice, people choose to work the rule until the clouds of accountability blow over.

When there’s something new to do, processes don’t do it – people do. When it’s time for some magical innovation, best practices don’t save the day – people do. Set the conditions for people to step up and they will; set the conditions for them to make a difference and they will. Use best practices if you must, but hold onto the fact that whatever business you’re in, you’re in the people business.

Image credit – Vicki & Chuck Rogers

Strategic Planning is Dead.

Things are no longer predictable, and it’s time to start behaving that way.

Things are no longer predictable, and it’s time to start behaving that way.

In the olden days (the early 2000s) the pace of change was slow enough that for most the next big thing was the same old thing, just twisted and massaged to look like the next big thing. But that’s not the case today. Today’s pace is exponential, and it’s time to behave that way. The next big thing has yet to be imagined, but with unimaginable computing power, smart phones, sensors on everything and a couple billion new innovators joining the web, it should be available on Alibaba and Amazon a week from next Thursday. And in three weeks, you’ll be able to buy a 3D printer for $199 and go into business making the next big thing out of your garage. Or, you can grasp tightly onto your success and ride it into the ground.

To move things forward, the first thing to do is to blow up the strategic planning process and sweep the pieces into the trash bin of a bygone era. And, the next thing to do is make sure the scythe of continuous improvement is busy cutting waste out of the manufacturing process so it cannot be misapplied to the process of re-imagining the strategic planning process. (Contrary to believe, fundamental problems of ineffectiveness cannot be solved with waste reduction.)

First, the process must be renamed. I’m not sure what to call it, but I am sure it should not have “planning” in the name – the rate of change is too steep for planning. “Strategic adapting” is a better name, but the actual behavior is more akin to probe, sense, respond. The logical question then – what to probe?

[First, for the risk minimization community, probing is not looking back at the problems of the past and mitigating risks that no longer apply.]

Probing is forward looking, and it’s most valuable to probe (purposefully investigate) fertile territory. And the most fertile ground is defined by your success. Here’s why. Though the future cannot be predicted, what can be predicted is your most profitable business will attract the most attention from the billion, or so, new innovators looking to disrupt things. They will probe your business model and take it apart piece-by-piece, so that’s exactly what you must do. You must probe-sense-respond until you obsolete your best work. If that’s uncomfortable, it should be. What should be more uncomfortable is the certainty that your cash cow will be dismantled. If someone will do it, it might as well be you that does it on your own terms.

Over the next year the most important work you can do is to create the new technology that will cause your most profitable business to collapse under its own weight. It doesn’t matter what you call it – strategic planning, strategic adapting, securing the future profitability of the company – what matters is you do it.

Today’s biggest risk is our blindness to the immense risk of keeping things as they are. Everything changes, everything’s impermanent – especially the things that create huge profits. Your most profitable businesses are magnates to the iron filings of disruption. And it’s best to behave that way.

Image credit – woodleywonderworks

Change your risk disposition.

Innovation creates things that are novel, useful and successful. Something that’s novel is something that’s different, and something that’s different creates uncertainty. And, as we know, uncertainty is the enemy of all things sacred.

Innovation creates things that are novel, useful and successful. Something that’s novel is something that’s different, and something that’s different creates uncertainty. And, as we know, uncertainty is the enemy of all things sacred.

Lean and Six Sigma have been so successful that the manufacturing analogy has created a generation that expects all things to be predictable, controllable and repeatable. Above all else, this generation values certainty. Make the numbers; reduce variability; reduce waste; do it on time – all mantras of the manufacturing analogy, all advocates of predictability and all enemies of uncertainty.

With the manufacturing analogy, a culture of accountability is the natural end game (especially when it comes to outcomes), but what most don’t understand is a culture that values accountability of outcomes is a culture that cannot tolerate uncertainty. And what fewer understand is a culture intolerant of uncertainty is a culture intolerant of innovation.

By definition, innovation and uncertainty are a matched pair – you can’t have one without the other. You can have both or neither – that’s the rule. And though we usually use the word “risk” rather than “uncertainty”, risk is a result of uncertainty and uncertainty is the fundamental.

When a product is launched and it’s poorly received, it’s likely due to an untested value proposition. And the reason the value proposition went untested is uncertainty, uncertainty around the negative consequences of challenging authority. Someone on high decreed the value proposition was real and the organization, based on how leadership responded in the past, did not challenge the decree because the last person who challenged authority was fired, demoted or ostracized.

When the new product is 3% better than the last one, again, the enemy is uncertainty. This time it’s either uncertainty around what the customer will value or uncertainty around the ability to execute on technology work. The organization cannot tolerate the risk (uncertainty), so it does what it did last time.

When the new product has more new features and functions than it has a right to, intolerance to uncertainty is the root cause. This time it’s uncertainty around the negative consequences of prioritizing one feature over another. Said another way, it’s about uncertainty (and the resulting fear) around using judgement.

These three scenarios are reward looking, as the uncertainty has already negatively impacted the innovation work. To mitigate the negative impacts on innovation, uncertainty must be part of the equation from the outset.

When it’s time for you to call for more innovation, it’s also the time to acknowledge you want more uncertainty. And it’s not enough to say you’ll tolerate more uncertainty because that takes you off the hook and puts it all on the innovators. You must tell the company you expect more uncertainty. This is important because the innovators won’t limit their work by an unnaturally low uncertainty threshold, rather they’ll do the work demanded by the hyper-aggressive growth goals.

And when you ask for more uncertainty, it’s time to explicitly tell people you expect them to use their judgment more freely and more frequently. With uncertainty there is no best practice, but there is best judgment. And when your best people use their best judgement, uncertainty is navigated in the most effective way.

But, really, if you ask for more uncertainty you won’t get it. The level of uncertainty in the trenches is set by your risk disposition. People in your company know, based on leadership’s actions – what’s rewarded and what’s punished – the company’s risk disposition and it governs their actions. If you take the pulse of your portfolio of technology projects you will see your risk disposition. The thing to remember is your risk disposition is the boss and the level of innovation is subservient.

When the CEO demands you change the innovation work for the better, politely suggest a plan to change the company’s risk disposition. And when the CEO asks how to do that, politely suggest a visit to Jim McCormick’s website.

Image credit – Suzanne Gerber

Innovation is alive and well.

Innovation isn’t a thing in itself; rather, it’s a result of something. Set the right input conditions, monitor the right things in the right ways, and innovation weaves itself into the genetic makeup of your company. Like ivy, it grabs onto outcroppings that are the heretics and wedges itself into the cracks of the organization. It grows unpredictably, it grows unevenly, it grows slowly. And one day you wake up and your building is covered with the stuff.

Innovation isn’t a thing in itself; rather, it’s a result of something. Set the right input conditions, monitor the right things in the right ways, and innovation weaves itself into the genetic makeup of your company. Like ivy, it grabs onto outcroppings that are the heretics and wedges itself into the cracks of the organization. It grows unpredictably, it grows unevenly, it grows slowly. And one day you wake up and your building is covered with the stuff.

Ivy doesn’t grow by mistake – It takes some initial plantings in strategic locations, some water, some sun, something to attach to, a green thumb and patience. Innovation is the same way.

There’s no way to predict how ivy will grow. One young plant may dominate the others; one trunk may have more spurs and spread broadly; some tangles will twist on each other and spiral off in unforeseen directions; some vines will go nowhere. Though you don’t know exactly how it will turn out, you know it will be beautiful when the ivy works its evolutionary magic. And it’s the same with innovation.

Ivy and innovation are more similar than it seems, and here are some rules that work for both:

- If you don’t plant anything, nothing grows.

- If growing conditions aren’t right, nothing good comes of it.

- Without worthy scaffolding, it will be slow going.

- The best time to plant the seeds was three years ago.

- The second best time to plant is today.

- If you expect predictability and certainty, you’ll be frustrated.

Innovation is the output of a set of biological systems – our people systems – and that’s why it’s helpful to think of innovation as if it’s alive because, well, it is. And like with a thriving colony of ants that grows steadily year-on-year, these living systems work well. From 10,000 foot perspective ants and innovation look the same – lots of chaotic scurrying, carrying and digging. And from an ant-to-ant, innovator-to-innovator perspective they are the same – individuals working as a coordinated collective within a shared mindset of long term sustainability.

Image credit – Cindy Cornett Seigle

Compete with No One

Today’s commercial environment is fierce. All companies have aggressive growth objectives that must be achieved at all costs. But there’s a problem – within any industry, when the growth goals are summed across competitors, there are simply too few customers to support everyone’s growth goals. Said another way, there are too many competitors trying to eat the same pie. In most industries it’s fierce hand-to-hand combat for single-point market share gains, and it’s a zero sum game – my gain comes at your loss. Companies surge against each other and bloody skirmishes break out over small slivers of the same pie.

Today’s commercial environment is fierce. All companies have aggressive growth objectives that must be achieved at all costs. But there’s a problem – within any industry, when the growth goals are summed across competitors, there are simply too few customers to support everyone’s growth goals. Said another way, there are too many competitors trying to eat the same pie. In most industries it’s fierce hand-to-hand combat for single-point market share gains, and it’s a zero sum game – my gain comes at your loss. Companies surge against each other and bloody skirmishes break out over small slivers of the same pie.

The apex of this glorious battle is reached when companies no longer have points of differentiation and resort to competing on price. This is akin to attrition warfare where heavy casualties are taken on both sides until the loser closes its doors and the winner emerges victorious and emaciated. This race to the bottom can only end one way – badly for everyone.

Trench warfare is no way for a company to succeed, and it’s time for a better way. Instead of competing head-to-head, it’s time to compete with no one.

To start, define the operating envelope (range of inputs and outputs) for all the products in the market of interest. Once defined, this operating envelope is off limits and the new product must operate outside the established design space. By definition, because the new product will operate with input conditions that no one else’s can and generate outputs no one else can, the product will compete with no one.

In a no-to-yes way, where everyone’s product says no, yours is reinvented to say yes. You sell to customers no one else can; you sell into applications no one else can; you sell functions no one else can. And in a wicked googly way, you say no to functions that no one else would dare. You define the boundary and operate outside it like no one else can.

Competing against no one is a great place to be – it’s as good as trench warfare is bad – but no one goes there. It’s straightforward to define the operating windows of products, and, once define it’s straightforward to get the engineers to design outside the window. The hard part is the market/customer part. For products that operate outside the conventional window, the sales figures are the lowest they can be (zero) and there are just as many customers (none). This generates extreme stress within the organization. The knee-jerk reaction is to assign the wrong root cause to the non-existent sales. The mistake – “No one sells products like that today, so there’s no market there.” The truth – “No one sells products like that today because no one on the planet makes a product like that today.”

Once that Gordian knot is unwound, it’s time for the marketing community to put their careers on the line. It’s time to push the organization toward the scary abyss of what could be very large new market, a market where the only competition would be no one. And this is the real hard part – balancing the risk of a non-existent market with the reward of a whole new market which you’d call your own.

If slugging it out with tenacious competitors is getting old, maybe it’s time to compete with no one. It’s a different battle with different rules. With the old slug-it-out war of attrition, there’s certainty in how things will go – it’s certain the herd will be thinned and it’s certain there’ll be heavy casualties on all fronts. With new compete-with-no-one there’s uncertainty at every turn, and excitement. It’s a conflict governed by flexibility, adaptability, maneuverability and rapid learning. Small teams work in a loosely coordinated way to test and probe through customer-technology learning loops using rough prototypes and good judgement.

It’s not practical to stop altogether with the traditional market share campaign – it pays the bills – but it is practical to make small bets on smart people who believe new markets are out there. If you’re lucky enough to have folks willing to put their careers on the line, competing with no one is a great way to create new markets and secure growth for future generations.

Image credit – mae noelle

Purposeful Violation of the Prime Directive

In Star Trek, the Prime Directive is the over-arching principle for The United Federation of Planets. The intent of the Prime Directive is to let a sentient species live in accordance with its normal cultural evolution. And the rules are pretty simple – do whatever you want as long as you don’t violate the Prime Directive. Even if Star Fleet personnel know the end is near for the sentient species, they can do nothing to save it from ruin.

In Star Trek, the Prime Directive is the over-arching principle for The United Federation of Planets. The intent of the Prime Directive is to let a sentient species live in accordance with its normal cultural evolution. And the rules are pretty simple – do whatever you want as long as you don’t violate the Prime Directive. Even if Star Fleet personnel know the end is near for the sentient species, they can do nothing to save it from ruin.

But what does it mean to “live in accordance with the normal cultural evolution?” To me it means “preserve the status quo.” In other words, the Prime Directive says – don’t do anything to challenge or change the status quo.

Though today’s business environment isn’t Star Trek and none of us work for Star Fleet, there is a Prime Directive of sorts. Today’s Prime Directive deals not with sentient species and their cultures but with companies and their business models, and its intent is to let a company live in accordance with the normal evolution of its business model. And the rules are pretty simple – do whatever you want as long as you don’t violate the Prime Directive. Even if company leaders know the end is near for the business model, they can do nothing to save it from ruin.

Business models, and their decrepit value propositions propping them up, don’t evolve. They stay just as they are. From inside the company the business model and value proposition are the very things that provide sustenance (profitability). They are known and they are safe – far safer than something new – and employees defend them as diligently as Captain Kirk defends his Prime Directive. With regard to business models, “to live in accordance with its natural evolution” is to preserve the status quo until it goes belly up. Today’s Prime Directive is the same as Star Trek’s – don’t do anything to challenge or change the status quo.

Innovation brings to life things that are novel, useful, and successful. And because novel is the same as different, innovation demands complete violation of today’s Prime Directive. For innovators to be successful, they must blow up the very things the company holds dear – the declining business model and its long-in-the-tooth value proposition.

The best way to help innovators do their work is to provide them phasers so they can shoot those in the way of progress, but even the most progressive HR departments don’t yet sanction phasers, even when set to “stun”. The next best way is to educate the company on why innovation is important. Company leaders must clearly articulate that business models have a finite life expectancy (measured in years, not decades) and that it’s the company’s obligation to disrupt and displace it.them.

The Prime Directive has a valuable place in business because it preserves what works, but it needs to be amended for innovation. And until an amendment is signed into law, company leaders must sanction purposeful violation of the Prime Directive and look the other way when they hear the shrill ring a phaser emanating from the labs.

Image credit – svenwerk

Systematic Innovation

Innovation is a journey, and it starts from where you are. With a systematic approach, the right information systems are in place and are continuously observed, decision makers use the information to continually orient their thinking to make better and faster decisions, actions are well executed, and outcomes of those actions are fed back into the observation system for the next round of orientation. With this method, the organization continually learns as it executes – its thinking is continually informed by its environment and the results of its actions.

Innovation is a journey, and it starts from where you are. With a systematic approach, the right information systems are in place and are continuously observed, decision makers use the information to continually orient their thinking to make better and faster decisions, actions are well executed, and outcomes of those actions are fed back into the observation system for the next round of orientation. With this method, the organization continually learns as it executes – its thinking is continually informed by its environment and the results of its actions.

To put one of these innovation systems in place, the first step is to define the group that will make the decisions. Let’s call them the Decision Group, or DG for short. (By the way, this is the same group that regularly orients itself with the information steams.) And the theme of the decisions is how to deploy the organization’s resources. The decision group (DG) should be diverse so it can see things from multiple perspectives.

The DG uses the company’s mission and growth objectives as their guiding principles to set growth goals for the innovation work, and those goals are clearly placed within the context of the company’s mission.

The first action is to orient the DG in the past. Resources are allocated to analyze the product launches over the past ten years and determine the lines of ideality (themes of goodness, from the customers’ perspective). These lines define the traditional ideality (traditional themes of goodness provided by your products) are then correlated with historical profitability by sales region to evaluate their importance. If new technology projects provide value along these traditional lines, the projects are continuous improvement projects and the objective is market share gain. If they provide extreme value along traditional lines, the projects are of the dis-continuous improvement flavor and their objective is to grow the market. If the technology projects provide value along different lines and will be sold to a different customer base, the projects could be disruptive and could create new markets.

The next step is to put in place externally focused information streams which are used for continuous observation and continual orientation. An example list includes: global and regional economic factors, mergers/acquisitions/partnerships, legal changes, regulatory changes, geopolitical issues, competitors’ stock price and quarterly updates, and their new products and patents. It’s important to format the output for easy visualization and to make collection automatic.

Then, internally focused information streams are put in place that capture results from the actions of the project team and deliver them, as inputs, for observation and orientation. Here’s an example list: experimental results (technology and market-centric), analytical results (technical and market), social media experiments, new concepts from ideation sessions (IBEs), invention disclosures, patent filings, acquisition results, product commercialization results and resulting profits. These information streams indicate the level of progress of the technology projects and are used with the external information streams to ground the DG’s orientation in the achievements of the projects.

All this infrastructure, process, and analysis is put in place to help the DG make good (and fast) decisions about how to allocate resources. To make good decisions, the group continually observes the information streams and continually orients themselves in the reality of the environment and status of the projects. At this high level, the group decides not how the project work is done, rather what projects are done. Because all projects share the same resource pool, new and existing projects are evaluated against each other. For ongoing work the DG’s choice is – stop, continue, or modify (more or less resources); and for new work it’s – start, wait, or never again talk about the project.

Once the resource decision is made and communicated to the project teams, the project teams (who have their own decision groups) are judged on how well the work is executed (defined by the observed results) and how quickly the work is done (defined by the time to deliver results to the observation center.)

This innovation system is different because it is a double learning loop. The first one is easy to see – results of the actions (e.g., experimental results) are fed back into the observation center so the DG can learn. The second loop is a bit more subtle and complex. Because the group continuously re-orients itself, it always observes information from a different perspective and always sees things differently. In that way, the same data, if observed at different times, would be analyzed and synthesized differently and the DG would make different decisions with the same data. That’s wild.

The pace of this double learning loop defines the pace of learning which governs the pace of innovation. When new information from the streams (internal and external) arrive automatically and without delay (and in a format that can be internalized quickly), the DG doesn’t have to request information and wait for it. When the DG makes the resource-project decisions it’s always oriented within the context of latest information, and they don’t have to wait to analyze and synthesize with each other. And when they’re all on the same page all the time, decisions don’t have to wait for consensus because it already has. And when the group has authority to allocate resources and chooses among well-defined projects with clear linkage to company profitability, decisions and actions happen quickly. All this leads to faster and better innovation.

There’s a hierarchical set of these double learning loops, and I’ve described only the one at the highest level. Each project is a double learning loop with its own group of deciders, information streams, observation centers, orientation work and actions. These lower level loops are guided by the mission of the company, goals of the innovation work, and the scope of their projects. And below project loops are lower-level loops that handle more specific work. The loops are fastest at the lowest levels and slowest at the highest, but they feed each other with information both up the hierarchy and down.

The beauty of this loop-based innovation system is its flexibility and adaptability. The external environment is always changing and so are the projects and the people running them. Innovation systems that employ tight command and control don’t work because they can’t keep up with the pace of change, both internally and externally. This system of double loops provides guidance for the teams and sufficient latitude and discretion so they can get the work done in the best way.

The most powerful element, however, is the almost “living” quality of the system. Over its life, through the work itself, the system learns and improves. There’s an organic, survival of the fittest feel to the system, an evolutionary pulse, that would make even Darwin proud.

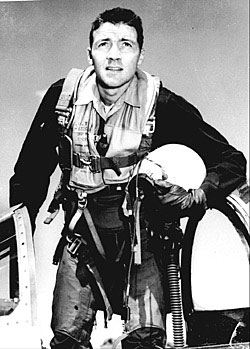

But, really, it’s Colonel John Boyd who should be proud because he invented all this. And he called it the OODA loop. Here’s his story – Boyd: The Fighter Pilot Who Changed the Art of War.

Where possible, I have used Boyd’s words directly, and give him all the credit. Here is a list of his words: observe, orient, decide, act, analyze-synthesize, double loop, speed, organic, survival of the fittest, evolution.

Image attribution – U.S. Government [public domain]. by wikimedia commons.

The Certainty of Uncertainty

When the output cannot be predicted, that’s uncertainty. And if there’s one thing to be certain of it’s uncertainty is always part of the equation.

When the output cannot be predicted, that’s uncertainty. And if there’s one thing to be certain of it’s uncertainty is always part of the equation.

With uncertainty, the generally accepted practice is minimization, and the method of choice is to control inputs. The best example is a high volume manufacturing process where inputs are controlled to reduce variation of the output (or reduce the uncertainty around goodness). Six Sigma tightens the screws on suppliers, materials, process steps, assembly tools and measurement gear so the first car off the production line is the same as the last one. That way, customers are certain to get what they’re promised. Minimization of uncertainty makes a lot of sense in the manufacturing analogy.

But there’s no free lunch with uncertainty, and the price of all this control is inflexibility. The manufacturing process can do only what it’s designed to do – to make what it was designed to make – and no more. And it can provide certainty of output only over a finite input range. Within the appropriate range of inputs there is certainty, but outside that range there is uncertainty. Even in the most well defined, highly controlled processes where great expense is taken to reduce uncertainty, there is uncertainty. Even the best automotive assembly lines can be disrupted by things like tsunamis, earthquakes, epidemics and labor strikes (100% certainty doesn’t exist). But still, in the manufacturing context minimization of uncertainty is a sound strategy.

When the intent of a process is to do things that have never been done and to bring new things to life, minimization of uncertainty is directionally incorrect. Said a different way, creativity and innovation demand uncertainty. More clearly – if there’s no uncertainty in the trenches, there’s no innovation.

The manufacturing analogy has been pushed too far from the factory. Just as Six Sigma has eliminated variation (and uncertainty) from things it shouldn’t (creativity work), lean and its two uncertainty killers (best practices and standard work) have been jammed into the gears of innovation and gummed up the works.

Standard work and best practices were invented to reduce variation in how work is done with the objective of, you guessed it, reducing uncertainty. The idea is to continuously improve and converge on the right recipe (sequence of operations or process steps) so the work is done the same way every-day-all-day. By definition, innovation work (the process steps) is never done the same way twice. The rule with best practices is simple – it should be reused every time there’s a need for that exact process. That makes sense. But it makes no sense to use a best practice when a process is done for the first time.

[Okay, the purists say that all transactional elements of innovation should follow standard work, and theoretically that’s right. But practically, the backwash of standard work, even when applied to transactional work, infects the psyche of the innovator and reduces uncertainty where uncertainty should be bolstered.]

Uncertainty is an important part of innovation, but it should not be maximized (it’s as inappropriate as minimizing). And there is no best practice for calculating the right amount. To strike a good balance, hold onto the fact that uncertainty and flexibility are a matched pair, and when doing something for the first time flexibility is a friend. And when standard work and best practices are imposed in the name of innovation efficiency, remember it’s far more important to have innovation effectiveness.

Image credit – NMK Photography

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski