There is no control. There is only trust.

Control strategies don’t work, but trust strategies do.

Control strategies don’t work, but trust strategies do.

Nothing goes as planned. Trying to control things tightly is wasteful. It takes too much energy to batten down all the hatches and keep them that way every-day-all-day. Maybe no water gets in, but the crew doesn’t get enough oxygen and their brains wither.

Trust on the other hand, is flexible and far more efficient. It takes little energy to hire a pro, give them the right task and get out of the way. And with the best pros it requires even less energy because the three-step becomes a two-step – hire them and get out of the way.

When both hands are continuously busy pulling the levers of contingency plans there are no hands left to point toward the future. When both arms are clinging onto the artificial schedule of the project plan there are no arms left to conduct the orchestra. Control strategies make sure even the piccolo plays the right notes at the right time, while trust strategies let the violins adjust based on their ear and intuition and even let the conductors write their own sheet music.

Control is an illusion, but trust is real. The best statistical analyses are rearward-looking and provide no control in a changing environment. (You can’t drive a car by looking in the rear view mirror.) Yet, that’s the state-of-the-art for control strategies – don’t change the inputs, don’t change the process and we’ll get what we got last time. That’s not control. That’s self-limiting.

Trust is real because people and their relationships are real. Trust is a contract between people where one side expects hard work and good judgment and the other side expects to be challenged and to be given the flexibility to do the work as they see fit. Trust-based systems are far more adaptable than if-then control strategies. No control algorithm can effectively handle unanticipated changes in input conditions or unplanned drift in decision criteria, but people and their judgement can. In fact, that’s what people are good at, and they enjoy doing it. And that’s a great recipe for an engaged work force.

Control strategies are popular because they help us believe we have control. And they’re ineffective for the same reason. Trust strategies are not popular because they acknowledge we have no real control and rely on judgment. And that’s why they’re effective.

When control strategies fail, trust strategies are implemented to save the day. When the wheels fall off a project, the best pro in the company is brought in to fix what’s broken. And the best pro is the most trusted pro. And their charge – Tell us what’s wrong (Use your judgement.), tell us how you’re going to fix it (Use your best judgement for that.) and tell us what you need to fix it. (And use your best judgement for that, too.)

In the end, trust trumps control. But only after all other possibilities are exhausted.

Image credit – Dobi.

All Your Mental Models are Obsolete

Even after playing lots of tricks to reduce its energy consumption, our brains still consume a large portion of the calories we eat. Like today’s smartphones it’s computing power is too big for it’s battery so its algorithms conserve every chance they get. One of its go-to conservation strategies is to make mental models. The models capture the essence of a system’s behavior without the overhead of retaining all the details of the system.

And as the brain goes about its day it tries to fit what it sees to its portfolio of mental models. Because mental models are so efficient, to save juice the brain is pretty loose with how it decides if a model fits the situation. In fact the brain doesn’t do a best fit, it does a first fit. Once a model is close enough, the model is applied, even if there’s a better one in the archives.

Overall, the brain does a good job. It looks at a system and matches it with a model of a similar system it experienced in the past. But behind it all the brain is making a dangerous assumption. The brain assumes all systems are static. And that makes for mental models that are static. And because all systems change over time (the only thing we can argue about is the rate of change) the brain’s mental models are always out of date.

Over the years your brain as made a mental model of how your business works – customers do this, competitors do that, and markets do the other. But by definition that mental model is outdated. There needs to be a forcing function that causes us to refute our mental models so we can continually refine them. [A good mantra could be – all mental models are out of fashion until proven otherwise.] But worse than not having a mechanism to refute them, we have a formal business process the demands we converge on our tired mental models year-on-year. And the name of that wicked process – strategic planning.

It goes something like this. Take a little time from your regular job (though you still have to do all that regular work) and figure out how you’re going to grow your business by a large (and arbitrary) percentage. The plan must be achievable (no pie in the sky stuff), it should be tightly defined (even though everyone knows things are dynamic and the plan will change throughout the year), you must do everything you did last year and more and you have fewer resources than last year. Any brain in it’s right will fit the old models to the new normal and put the plan together in the (insufficient) time allotted. The planning process reinforces the re-use of old models.

Because the brain believes everything is static, it’s thinking goes like this – a plan based on anything other than the tried-and-true mental models cannot have certainty or predictability in time or resources. And it’s thinking is right, in part. But because all mental models are out of date, even plans based on existing models don’t have certainty and predictability. And that’s where the wheels fall off.

To inject a bit more reality into strategic planning, ignore the tired old information streams that reinforce existing thinking and find new ones that provide information that contradicts existing mental models. Dig deeply into the mismatch between the new information and the old mental models. What is behind the difference? Is the difference limited to a specific region or product line? Is the mismatch new or has it always been there? The intent of this knee-deep dissection is not to invalidate the old models but to test and refine.

There is infinite detail in the world. Take a look at a tree and there’s a trunk and canopy. Look at the canopy and see the leaves. Look deeper to see a leaf and its veins. In order to effectively handle all this detail our brains create patterns and abstractions to reduce the amount of information needed to make it through the day.

In the case of the tree, the word “tree” is used to capture the whole thing – roots and all. And at a higher level, “tree” can represent almost any type of tree at almost any stage in its life. The abstraction is powerful because it reduces the complexity, as long as everyone’s clear which tree is which.

The message is this. Our brain takes shortcuts with its chunking of the world into mental models that go out style. And our brain uses different levels of abstraction for the same word to mean different things. Care must be taken to overtly question our mental models and overtly question the level of abstraction used when statements of facts are made.

Knowing what isn’t said is almost important as what is said. To maintain this level of clarity requires calm, centered awareness which today’s pace makes difficult.

There’s no pure cure for the syndrome. The best we can do is to be well-rested and aware. And to do that requires professional confidence and personal disciple.

Slowing down just a bit can be faster, and testing the assumptions behind our business models can be even faster. Last year’s mental models and business models should be thought of as guilty until proven relevant. And for that you need to make the time to think.

In today’s world we confuse activity with progress. But really, in today’s dynamic world thinking is progress.

Image credit – eyeliam.

Serious Business

If you’re serious about your work, you’re too serious. We’re all too bound up in this life-or-death, gotta-meet-the-deadline nonsense that does nothing but get in the way.

If you’re serious about your work, you’re too serious. We’re all too bound up in this life-or-death, gotta-meet-the-deadline nonsense that does nothing but get in the way.

If you’re into following recipes, I guess it’s okay to be held accountable to measuring the ingredients accurately and mixing the cake batter with 110% effort. When your business is serious about making more cakes than anyone else on the planet, it’s fine to take that seriously. But if you’re into making recipes, serious doesn’t cut it. Coming up with new recipes demands the freedom of putting together spices that have never been combined. And if you’re too serious, you’ll never try that magical combination that no one else dared.

Serious is far different than fully committed and “all in.” With fully committed, you bring everything you have, but you don’t limit yourself by being too serious. When people are too serious they pucker up and do what they did last time. With “all in” it’s just that – you put all your emotional chips on the line and you tell the dealer to “hit.” If the cards turn in your favor you cash in in a big way. If you bust, you go home, rejuvenate and come back in the morning with that same “all in” vigor you had yesterday and just as many chips. When you’re too serious, you bet one chip at a time. You don’t bet many chips, so you don’t lose many. But you win fewer.

The opposite of serious is not reckless. The opposite of serious is energetic, extravagant, encouraging, flexible, supportive and generous. A culture of accountability is serious. A culture of creativity is not.

I do not advocate behavior that is frivolous. That’s bad business. I do advocate behavior that is daring. That’s good business. Serious connotes measurable and quantifiable, and that’s why big business and best practices like serious. But measurable and quantifiable aren’t things in themselves. If they bring goodness with them, okay. But there’s a strong undercurrent of measurable for measurable’s sake. It’s like we’re not sure what to do, so we measure the heck out of everything. Daring, on the other hand, requires trust is unmeasurable. Never in the history of Six Sigma has there been a project done on daring and never has one of its control strategies relied on trust. That’s because Six Sigma is serious business. Serious connotes stifling, limiting and non-trusting, and that’s just what we don’t need.

Let’s face it, Six Sigma and lean are out of gas. So is tightening-the-screws management. The low hanging fruit has been picked and Human Resources has outed all the mis-fits and malcontents. There’s nothing left to cut and no outliers to eliminate. It’s time to put serious back in its box.

I don’t know what they teach in MBA programs, but I hope it’s trust. And I don’t know if there’s anything we can do with all our all-too-serious managers, but I hope we put them on a program to eliminate their strengths and build on their weaknesses. And I hope we rehire the outliers we fired because they scared all the serious people with their energy, passion and heretical ideas.

When you’re doing the same thing every day, serious has a place. When you’re trying to create the future, it doesn’t. To create the future you’ve got to hire heretics and trust them. Yes, it’s a scary proposition to try to create the future on the backs of rabble-rousers and rebels. But it’s far scarier to try to create it with the leagues of all-too-serious managers that are running your business today.

Image credit — Alan

Solving Intractable Problems

Immediately after there’s an elegant solution to a previously intractable problem, the solution is obvious to others. But, just before the solution those same folks said it was impossible to solve. I don’t know if there’s a name for this phenomenon, but it certainly causes hart burn for those brave enough to take on the toughest problems.

Immediately after there’s an elegant solution to a previously intractable problem, the solution is obvious to others. But, just before the solution those same folks said it was impossible to solve. I don’t know if there’s a name for this phenomenon, but it certainly causes hart burn for those brave enough to take on the toughest problems.

Intractable problems are so fundamental they are no longer seen as problems. Over the years experts simply accept these problems as constraints that must be complied with. Just as the laws of physics can’t be broken, experts behave as if these self-made constraints are iron-clad and believe these self-build walls define the viable design space. To experts, there is only viable design space or bust.

A long time ago these problems were intractable, but now they are not. Today there are new materials, new analysis techniques, new understanding of physics, new measurement systems and new business models.. But, they won’t be solved. When problems go unchallenged and constrain design space they weave themselves into the fabric of how things are done and they disappear. No one will solve them until they are seen for what they are.

It takes time to slow down and look deeply at what’s really going on. But, today’s frantic pace, unnatural fascination with productivity and confusion of activity with progress make it almost impossible to slow down enough to see things as they are. It takes a calm, centered person to spot a fundamental problem masquerading as standard work and best practice. And once seen for what they are it takes a courageous person to call things as they are. It’s a steep emotional battle to convince others their butts have been wet all these years because they’ve been sitting in a mud puddle.

Once they see the mud puddle for what it is, they must then believe it’s actually possible to stand up and walk out of the puddle toward previously non-viable design space where there are dry towels and a change of clothes. But when your butt has always been wet, it’s difficult to imagine having a dry one.

It’s difficult to slow down to see things as they are and it’s difficult to re-map the territory. But it’s important. As continuous improvement reaches the limit of diminishing returns, there are no other options. It’s time to solve the intractable problems.

Image credit – Steven Depolo

Hands-On or Hands-Off?

Hands-on versus hands-off – as a leader it’s a fundamental choice. And for me the single most important guiding principle is – do what it takes to maintain or strengthen the team’s personal ownership of the work.

Hands-on versus hands-off – as a leader it’s a fundamental choice. And for me the single most important guiding principle is – do what it takes to maintain or strengthen the team’s personal ownership of the work.

If things are going well, keep your hands off. This reinforces the team’s ownership and your trust in them. But it’s not hands-off in and ignore them sense; it’s hands-off in a don’t tell them what to do sense. Walk around, touch base and check in to show interest in the work and avoid interrogation-based methods that undermine your confidence in them. This is not to say a hands-off leader only superficially knows what’s going on, it should only look like the leader has a superficial understanding.

The hands-off approach requires a deep understanding of the work and the people doing it. The hands-off leader must make the time to know the GPS coordinates of the project and then do reconnaissance work to identify the positions of the quagmires and quicksand that lay ahead. The hands-off leader waits patiently just in front of the obstacles and makes no course correction if the team can successfully navigate the gauntlet. But when the team is about to sink to their waists, leader gently nudges so they skirt the dangerous territory.

Unless, of course, the team needs some learning. And in that case, the leader lets the team march it’s project into the mud. If they need just a bit of learning the leader lets them get a little muddy; and if the team needs deep learning, the leader lets them sink to their necks. Either way, the leader is waiting under cover as they approach the impending snafu and is right beside them to pull them out. But to the team, the hands-off leader is not out in front scouting the new territory. To them, the hands-off leader doesn’t pay all that much attention. To the team, it’s just a coincidence the leader happens to attend the project meeting at a pivotal time and they don’t even recognize when the leader subtly plants the idea that lets the team pull themselves out of the mud.

If after three or four near-drowning incidents the team does not learn or change it’s behavior, it’s time for the hands-off approach to look and feel more hands-on. The leader calls a special meeting where the team presents the status of the project and grounds the project in the now. Then, with everyone on the same page the leader facilitates a process where the next bit of work is defined in excruciating detail. What is the next learning objective? What is the test plan? What will be measured? How will it be measured? How will the data be presented? If the tests go as planned, what will you know? What won’t you know? How will you use the knowledge to inform the next experiments? When will we get together to review the test results and your go-forward recommendations?

By intent, this tightening down does not go unnoticed. The next bit of work is well defined and everyone is clear how and when the work will be completed and when the team will report back with the results. The leader reverts back to hands-off until the band gets back together to review the results where it’s back to hands-on. It’s the leader’s judgement on how many rounds of hands-on roulette the team needs, but the fun continues until the team’s behavior changes or the project ends in success.

For me, leadership is always hands-on, but it’s hands-on that looks like hands-off. This way the team gets the right guidance and maintains ownership. And as long as things are going well this is a good way to go. But sometimes the team needs to know you are right there in the trenches with them, and then it’s time for hands-on to look like hands-on. Either way, its vital the team knows they own the project.

There are no schools that teach this. The only way to learn is to jump in with both feet and take an active role in the most important projects.

Image credit – Kerri Lee Smith

The Fear of Being Judged

“Here – I made this.” Those are courageous words. When you make something no one has made and you show people you are saying to yourself – “I know my work will be judged, but that’s the price of putting myself out there. I will show my work anyway.” I think the fear of being judged is enemy number one of creativity, innovation, and living life on your own terms. If I had ten dollars of courage in my pocket I’d spend it to dampen my fear of being judged.

“Here – I made this.” Those are courageous words. When you make something no one has made and you show people you are saying to yourself – “I know my work will be judged, but that’s the price of putting myself out there. I will show my work anyway.” I think the fear of being judged is enemy number one of creativity, innovation, and living life on your own terms. If I had ten dollars of courage in my pocket I’d spend it to dampen my fear of being judged.

No one has ever died from the fear of being judged, but right before you show your new work, share your inner feelings or show your true self, is sure feels like you’re going to be the exception. The fear of being judged is powerful enough to generate self-limiting behavior and sometimes can completely debilitate. It’s vector of unpleasantness is huge.

At a lower level, the fear of being judged is the fear someone will think of you differently than you want them to. It’s a fear they’ll label you with a scarlet letter you don’t want to own. This mismatch is the gradient that drives the fear. If you reduce the gradient you reduce the fear and the self-censorship.

No one can label you without your consent, and if you don’t consent there is no gradient. If you think the scarlet letter does not fit you, it doesn’t. No mismatch. When someone tries to hand you a gift and instead of taking it from them you let it drop to the floor, it’s not your gift. If you don’t accept their gift there is no gradient. But there is a gradient because you think the scarlet letter may actually fit and the gift may actually be yours. You create your fear because you think they may be right.

In the end it’s all about what you think about yourself. If your behavior is skillful and you know it, you will not accept someone else’s judgment and there’s no fear-fueling gradient . If your approach is purposefully thoughtful, you will not consent to labeling. If you know your intentions are true, there can be no external mismatch because there is no internal mismatch.

No one can be 100% skillful, purposeful, thoughtful and intentional. But directionally, behaving this way will reduce the gradient and the fear. But the fear will never go away, and that’s why we need courage. Be skillful and afraid and do it anyway. Be thoughtful and scared and do what scares you. Be true to your heart’s intention and just courageous as you need to be to wrestle your fears to the ground.

Image credit – Paul Townsend

A Life Boat in the Sea of Uncertainty

Work is never perfect, family life is never perfect and neither is the interaction between them. Regardless of your expectations or control strategies, things go as they go. That’s just what they do.

Work is never perfect, family life is never perfect and neither is the interaction between them. Regardless of your expectations or control strategies, things go as they go. That’s just what they do.

We have far less control than we think. In the pure domain of physics the equations govern predictively – perturb the system with a known input in a controlled way and the output is predictable. When the process is followed, the experimental results repeat, and that’s the acid test. From a control standpoint this is as good as it gets. But even this level of control is more limited than it appears.

Physical laws have bounded applicability – change the inputs a little and the equation may not apply in the same way, if at all. Same goes for the environment. What at the surface looks controllable and predictable, may not be. When the inputs change, all bets are off – the experimental results from one test condition may not be predictive in another, even for the simplest systems, In the cold, unemotional world of physical principles, prediction requires judgement, even in lab conditions.

The domains of business and life are nothing like controlled lab conditions. And they’re and not governed by physical laws. These domains are a collection of complex people systems which are governed by emotional laws. Where physics systems delivers predictable outputs for known inputs, people systems do not. Scenario 1. Your group’s best performer is overworked, tired, and hasn’t exercised in four weeks. With no warning you ask them to take on an urgent and important task for the CEO. Scenario 2. Your group’s best performer has a reasonable workload (and even a little discretionary time), is well rested and maintains a regular exercise schedule, and you ask for the same deliverable in the same way. The inputs are the same (the urgent request for the CEO), the outputs are far different.

At the level of the individual – the building block level – people systems are complex and adaptive, The first time you ask a person to do a task, their response is unpredictable. The next day, when you ask them to do a different task, they adapt their response based on yesterday’s request-response interaction, which results in a thicker layer of unpredictability. Like pushing on a bag of water, their response is squishy and it’s difficult to capture the nuance of the interaction. And it’s worse because it takes a while for them to dampen the reactionary waves within them.

One person interacts with another and groups react to other groups. Push on them and there’s really no telling how things will go. One cylo competes with another for shared resources and complexity is further confounded. The culture of a customer smashes against your standard operating procedures and the seismic pressure changes the already unpredictable transfer functions of both companies. And what about the customer that’s also your competitor? And what about the big customer you both share? Can you really predict how things will go? Do you really have control?

What does all this complexity, ambiguity, unpredictability and general lack of control mean when you’re trying to build a culture of accountability? If people are accountable for executing well, that’s fine. But if they’re held accountable for the results of those actions, they will fail and your culture of accountability will turn into a culture of avoiding responsibility and finding another place to work.

People know uncertainty is always part of the equation, and they know it results in unpredictability. And when you demand predictability in a system that’s uncertain by it’s nature, as a leader you lose credibility and trust.

As we swim together in the storm of complexity, trust is the life boat. Trust brings people together and makes it easier to row in the same direction. And after a hard day of mistakenly rowing in the wrong direction, trust helps everyone get back in the boat the next day and pull hard in the new direction you point them.

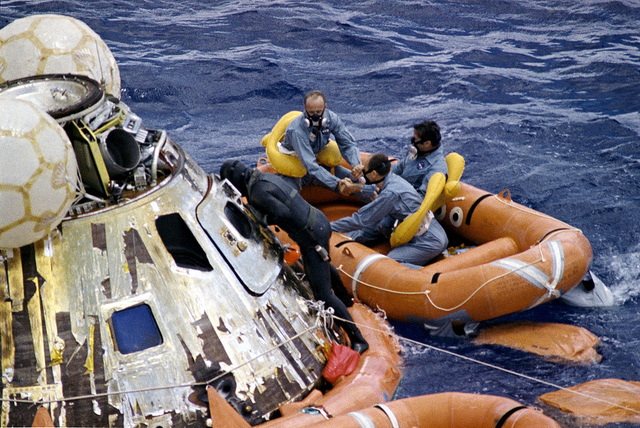

Image credit – NASA

Out of Context

“It’s a fact.” is a powerful statement. It’s far stronger than a simple description of what happened. It doesn’t stop at describing a sequence of events that occurred in the past, rather it tacks on an implication of what to think about those events. When “it’s a fact” there’s objective evidence to justify one way of thinking over another. No one can deny what happened, no one can deny there’s only one way to see things and no one can deny there’s only one way to think. When it’s a fact, it’s indisputable.

“It’s a fact.” is a powerful statement. It’s far stronger than a simple description of what happened. It doesn’t stop at describing a sequence of events that occurred in the past, rather it tacks on an implication of what to think about those events. When “it’s a fact” there’s objective evidence to justify one way of thinking over another. No one can deny what happened, no one can deny there’s only one way to see things and no one can deny there’s only one way to think. When it’s a fact, it’s indisputable.

Facts aren’t indisputable, they’re contextual. Even when an event happens right in front of two people, they don’t see it the same way. There are actually two events that occurred – one for each viewer. Two viewers, two viewing angles, two contexts, two facts. Right at the birth of the event there are multiple interpretations of what happened. Everyone has their own indisputable fact, and then, as time passes, the indisputables diverge.

On their own there’s no problem with multiple diverging paths of indisputable facts. The problem arises when we use indisputable facts of the past to predict the future. Cause and effect are not transferrable from one context to another, even if based on indisputable facts. The physics of the past (in the true sense of physics) are the same as the physics of today, but the emotional, political, organizational and cultural physics are different. And these differences make for different contexts. When the governing dynamics of the past are assumed to be applicable today, it’s easy to assume the indisputable facts of today are the same as yesterday. Our static view of the world is the underlying problem, and it’s an invisible problem.

We don’t naturally question if the context is different. Mostly, we assume contexts are the same and mostly we’re blind to those assumptions. What if we went the other way and assumed contexts are always different? What would it feel like to live in a culture that always questions the context around the facts? Maybe it would be healthy to justify why the learning from one situation applies to another.

As the pace of change accelerates, it’s more likely today’s context is different and yesterday’s no longer applies. Whether we want to or not, we’ll have to get better at letting go of indisputable facts. Instead of assuming things are the same, it’s time to look for what’s different.

Image credit — Joris Leermakers

Don’t worry about the words, worry about the work.

Doing anything for the first time is difficult. It goes with the territory. Instead of seeing the associated anxiety as unwanted and unpleasant, maybe you can use it as an indicator of importance. In that way, if you don’t feel anxious you know you’re doing what you’ve done before.

Doing anything for the first time is difficult. It goes with the territory. Instead of seeing the associated anxiety as unwanted and unpleasant, maybe you can use it as an indicator of importance. In that way, if you don’t feel anxious you know you’re doing what you’ve done before.

Innovation, as a word, has been over used (and misused). Some have used the word to repackage the same old thing and make it fresh again, but more commonly people doing good work attach the word innovation to their work when it’s not. Just because you improved something doesn’t mean it’s innovation. This is the confusion made by the lean and Six Sigma movements – continuous improvement is not innovation. The trouble with saying that out loud is people feel the distinction diminishes the importance of continuous improvement. Continuous improvement is no less important than innovation, and no more. You need them both – like shoes and socks. But problems arise when continuous improvement is done in the name of innovation and innovation is done at the expense of continuous improvement – in both cases it’s shoes, no socks.

Coming up with an acid test for innovation is challenging. Innovation is a know-it-when-you-see-it thing that’s difficult to describe in clear language. It’s situational, contextual and there’s no prescription. [One big failure mode with innovation is copying someone else’s best practice. With innovation, cutting and pasting one company’s recipe into another company’s context does not work.] But prescriptions and recipes aside, it can be important to know when it’s innovation and when it isn’t.

If the work creates the foundation that secures your company’s growth goals, don’t worry about what to call it, just do it. If that work doesn’t require something radically new and different, all-the-better. But you likely set growth goals that were achievable regardless of the work you did. But still, there’s no need to get hung up on the label you attach to the work. If the work helps you sell to customers you could not sell to before, call it what you will, but do more of it. If the work creates a whole new market, what you call it does not matter. Just hurry up and do it again.

If your CEO is worried about the long term survivability of your company, don’t fuss over labelling your work with the right word, do something different. If you have to lower your price to compete, don’t assign another name to the work, do different work. If your new product is the same as your old product, don’t argue if it’s the result of continuous improvement or discontinuous improvement. Just do something different next time.

Labelling your work with the right word is not the most important thing. It’s far more important to ask yourself – Five years from now, if the company is offering a similar product to a similar set of customers, what will it be like to work at the company? Said another way, arguing about who is doing innovation and who is not gets in the way of doing the work needed to keep the company solvent.

If the work scares you, that’s a good indication it’s meaningful. And meaningful is good. If it scares you because it may not work, you’re definitely trying something new. And that’s good. But it’s even better if the work scares you because it just might come to be. If that’s the case, your body recognizes the work could dismantle a foundational element of your business – it either invalidates your business model or displaces a fundamental technology. Regardless of the specifics, anxiety is a good surrogate for importance.

In some cases, it can be important what you call the work. But far more important than getting the name right is doing the right work. If you want to argue about something, argue if the work is meaningful. And once a decision is reached, act accordingly. And if you want to have a debate, debate the importance of the work, then do the important work as fast as you can.

Do the important work at the expense of arguing about the words.

It’s time to make a difference.

If on the first day on your new job your stomach is all twisted up with anxiety and you’re second guessing yourself because you think you took a job that is too big for you, congratulations. You got it right. The right job is supposed to feel that way. If on your first day you’re totally comfortable because you’ve done it all before and you know how it will go, you took the job for the money. And that’s a terrible reason to take a job.

If on the first day on your new job your stomach is all twisted up with anxiety and you’re second guessing yourself because you think you took a job that is too big for you, congratulations. You got it right. The right job is supposed to feel that way. If on your first day you’re totally comfortable because you’ve done it all before and you know how it will go, you took the job for the money. And that’s a terrible reason to take a job.

You got the job because someone who knew what it would take to get it done believed you were the right one to do just that. This wasn’t charity. There was something in it for them. They needed the job done and they wanted a pro. And they chose you. The fact their stomach isn’t in knots says nothing about their stomach and everything about their belief in you. And the knots in your stomach? That ‘s likely a combination of immense desire to do a good job and an on-the-low-side belief in yourself.

If we’re not stretching we’re not learning, and if we’re not learning we’re not living. So why the nerves? Why the self doubt? Why don’t we believe in ourselves? When we look inside, we see ourselves in the moment – in the now, as we are. And sometimes when we look inside there are only re-run stories of our younger selves. It’s difficult to see our future selves, to see our own growth trajectory from the inside. It’s far easier to see a growth trajectory from the outside. And that’s what the hiring team sees – our future selves – and that’s why they hire.

This growth-stretch, anxiety-doubt seesaw is not unique to new jobs. It’s applicable right down the line – from temporary assignments, big projects and big tasks down to small tasks with tight deliverables. If you haven’t done it before, it’s natural to question your capability. But if you trust the person offering the job, it should be natural to trust their belief in you.

When you sit in your new chair for the first time and you feel queasy, that’s not a sign of incompetence it’s a sign of significance. And it’s a sign you have an opportunity to make a difference. Believe in the person that hired you, but more importantly, believe in yourself. And go make a difference.

Image credit – Thomas Angermann

Are you striving or thriving?

Thriving is not striving. And they’re more than unrealated. They’re opposites.

Thriving is not striving. And they’re more than unrealated. They’re opposites.

Striving is about the now and what’s in it for me. Thriving is about the greater good and choosing – choosing to choose your own path and choosing to travel it in your own way. Thriving doesn’t thrive because outcomes fit with expectations. Thriving thrives on the journey.

Where striving comes at others’ expense, thriving comes at no one’s expense. Where striving strives on getting ahead, thriving thrives on growing. Striving looks outwardly, thriving looks inwardly. No two words are spelled so similarly yet contradict so vehemently.

Plants thrive when they’re put in the right growing conditions. They grow the way they were meant to grow and they don’t look back. They thrive because they don’t second guess themselves. If they don’t grow as tall as others, they’re happy for the tallest. And if they bloom bigger and brighter than the rest, they’re thoughtful enough to make conversation about other things.

Plants and animals don’t strive. Only people do. Strivers live their lives looking through the lens of the zero sum game. Strivers feel there’s not enough sunlight to go around so they reach and stretch and step on your head so they get a tan and leave you to supplement with vitamin D.

I can deal with strivers that tell you they’re going to step on your head and step on it just as they said. And I have immense disdain for strivers that pretend they’re sunflowers. But when I’m around thrivers I resonate.

Strivers suck energy from the room and thrivers give it way freely. And just as the bumblebee gets joy from spreading the love flower-to-flower, thrivers thrive more as they give more.

If you leave a meeting feeling good about yourself and three days later you rethink things and feel like a lesser person, you were victimized by a striver. If you feel great about yourself after a meeting and three days later feel even better, you rubbed shoulders with a thriver.

Learn to spot the strivers so you can distance yourself. And seek out the thrivers so you can grow with them.

Image credit Brad Smith

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski