Companies don’t innovate, people do.

Big companies hold tightly to what they have until they feel threatened by upstarts, and not before. They mobilize only when they see their sales figures dip below the threshold of tolerability, and no sooner. And if they’re the market leaders, they delay their mobilization through rationalization. The dip is due to general economic slowdown that is out of our control, the dip is due to temporary unrest from the power structure change in government, or the dip is due to some ethereal force we don’t yet fully understand. The strength of big companies is what they have, and they do what it takes only when what they have is threatened. But once they’re threatened, watch out. But, the truth is, big companies don’t make change, people within big companies make change.

Big companies hold tightly to what they have until they feel threatened by upstarts, and not before. They mobilize only when they see their sales figures dip below the threshold of tolerability, and no sooner. And if they’re the market leaders, they delay their mobilization through rationalization. The dip is due to general economic slowdown that is out of our control, the dip is due to temporary unrest from the power structure change in government, or the dip is due to some ethereal force we don’t yet fully understand. The strength of big companies is what they have, and they do what it takes only when what they have is threatened. But once they’re threatened, watch out. But, the truth is, big companies don’t make change, people within big companies make change.

Start-ups want to change everything. They reject what they don’t have and threaten the status-quo at every turn. And they’re always mobilized to grow sales. Every new opportunity brings an opportunity to change the game. In a ready-fire-aim way, every phone call with a potential customer is an opportunity to dilute and defocus. Each new opportunity is an opportunity to create a mega business and each new customer segment is an opportunity to pivot. The strength of start-ups is what they don’t have. No loyalty to an existing business model, no shared history with other companies, and no NIH (not invented here). But, once they focus and decide to converge on an important market segment, watch out. But, truth is, start-ups don’t make change, people within start-ups make change.

When you work in a big company, if your idea is any good the established business units will try to stomp it into oblivion because it threatens their status quo. In that way, if your idea is dismissed out of hand or stomped on aggressively, you are likely onto something worth pursuing. If you’re told by the experts “It will never work.” that’s a sign from the gods that your idea has strong merit and deserves to be worked. And this is where it comes down to people. The person with the idea can either pack it in or push through the intellectual inertia of company success. To be clear – it’s their choice. If they pack it in, the idea never sees the light of day. But if they decide, despite the fact they’re not given the tools, time, or training, to build a prototype and show it to company leadership, your company has a chance to reinvent itself. What causes and conditions have you put in place for your passionate innovators to choose to do the hard work of making a prototype?

When you work at a start-up the objective is to dismantle the status quo, and all ideas are good ideas. In that way, your idea will be praised and you’ll be urged to work on it. If you’re told by the experts “That could work.” it does not mean you should work on it. Since resources are precious, focus is mandatory. The person with the idea can either try to convert their idea into a prototype or respect the direction set by company leadership. To be clear – it’s their choice. If they work on their new idea they dilute the company’s best chance to grow. But if they decide, despite their excitement around their idea, to align with the direction set by the company, your startup has a chance to deliver on its aggressive promises. What causes and conditions have you put in place for your passionate innovators to choose to do the hard work of aligning with the agreed upon approach and direction?

When no one’s looking, do you want your people to try new ideas or focus on the ones you already have? When given a choice, do you want them to focus on existing priorities or blow them out of the water? And if you want to improve their ability to choose, what can you put in place to help them choose wisely?

To be clear, a formal set of decision criteria and a standardized decision-making process won’t cut it here. But that’s not to say decisions should be unregulated and unguided. The only thing that’s flexible and powerful enough to put things right is the good judgment of the middle managers who do the work. “Middle managers” is not the best words to describe who I’m talking about. I’m talking about the people you call when the wheels fall off and you need them put back on in a hurry. You know who I’m talking about. In start-ups or big companies, these people have a deep understanding of what the company is trying to achieve, they know how to do the work and know when to say “give it a try” and when to say “not now.” When people with ideas come to them for advice, it’s their calibrated judgement that makes the difference.

Calibrated judgement of respected leaders is not usually called out as a make-or-break element of innovation, growth and corporate longevity, but is just that. But good judgement around new ideas are the key to all three. And it comes down to a choice – do those ideas die in the trenches or are they kindly nurtured until they can stand on their own?

No getting around it, it’s a judgment call whether an idea is politely put on hold or accelerated aggressively. And no getting around it, those decisions make all the difference.

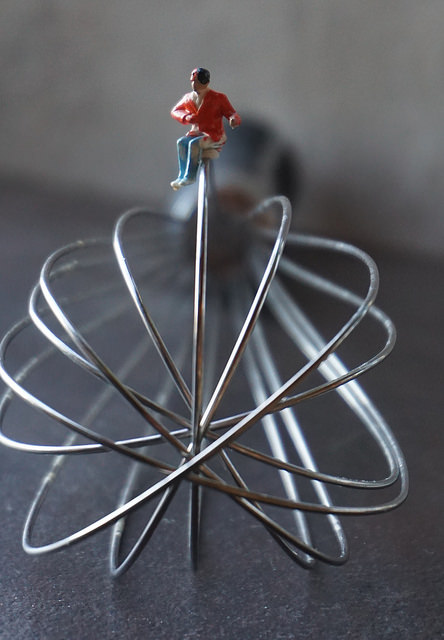

Image credit Mark Strozier

Working with uncertainty

Try – when you’re not sure what to do.

Try – when you’re not sure what to do.

Listen – when you want to learn.

Build – when you want to put flesh on the bones of your idea.

Think – when you want to make progress.

Show a customer – when you want to know what your idea is really worth.

Put it down – when you want your subconscious to solve a problem.

Define – when you want to solve.

Satisfy needs – when you want to sell products

Persevere – when the status quo kicks you in the shins.

Exercise – when you want set the conditions for great work.

Wait – when you want to run out of time and money.

Fear failure – when you want to block yourself from new work.

Fear success – when you want to stop innovation in its tracks.

Self-worth – when you want to overcome fear.

Sleep – when you want to be on your game.

Chance collision – when you want something interesting to work on.

Write – when you want to know what you really think.

Make a hand sketch – when you want to communicate your idea.

Ask for help – when you want to succeed.

Image credit – Daniel Dionne

Rule 1: Allocate resources for effectiveness.

We live in a resource constrained world where there’s always more work than time. Resources are always tighter than tight and tough choices must be made. The first choice is to figure out what change you want to make in the world. How do you want put a dent in the universe? What injustice do you want to put to rest? Which paradigm do you want to turn on its head?

We live in a resource constrained world where there’s always more work than time. Resources are always tighter than tight and tough choices must be made. The first choice is to figure out what change you want to make in the world. How do you want put a dent in the universe? What injustice do you want to put to rest? Which paradigm do you want to turn on its head?

In business and in life, the question is the same – How do you want to spend your time?

Before you can move in the right direction, you need a direction. At this stage, the best way to allocate your resources is to define the system as it is. What’s going on right now? What are the fundamentals? What are the incentives? Who has power? Who benefits when things move left and who loses when things go right? What are the main elements of the system? How do they interact? What information passes between them? You know you’ve arrived when you have a functional model of the system with all the elements, all the interactions and all the information flows.

With an understanding of how things are, how do you want to spend your time? Do you want to validate your functional model? If yes, allocate your resources to test your model. Run small experiments to validate (or invalidate) your worldview. If you have sufficient confidence in your model, allocate your resources to define how things could be. How do you want the fundamentals to change? What are the new incentives? Who do you want to have the power? And what are the new system elements, their new interactions and new information flows?

When working in the domain of ‘what could be’ the only thing to worry about is what’s next. What’s after the next step? Not sure. How many resources will be required to reach the finish line? Don’t know. What do we do after the next step? It depends on how it goes with this step. For those that are used to working within an efficiency framework this phase is a challenge, as there can be no grand plan, no way to predict when more resources will be needed and no way to guarantee resources will work efficiently. For the ‘what could be’ phase, it’s better to use a framework of effectiveness.

In a one-foot-in-front-of-the-other way, the only thing that matters in the ‘what could be’ domain is effectively achieving the next learning objective. It’s not important that the learning is done most efficiently, it matters that the learning is done well and done quickly. Efficiently learning the wrong thing is not effective. Running experiments efficiently without learning what you need to is not effective. And learning slowly but efficiently is not effective.

Allocate resources to learn what needs to be learned. Allocate resources to learn effectively, not efficiently. Allocate your best people and give them the time they need. And don’t expect an efficient path. There will be unplanned lefts and rights. There will be U-turns. There will times when there’s lots of thinking and little activity, but at this stage activity isn’t progress, thinking is. It may look like a drunkard’s walk, but that’s how it goes with this work.

When the objective of the work isn’t to solve the problem but to come up with the right question, allocate resources in a way that prioritizes effectiveness over efficiency. When working in the domain of ‘what could be’ allocate resources on the learning objective at hand. Don’t worry too much about the follow-on learning objectives because you may never earn the right to take them on.

In the domain of uncertainty, the best way to allocate the resources is to learn what you need to learn and then figure out what to learn next.

Image credit – John Flannery

The WHY and HOW of Innovation

Innovation is difficult because it demands new work. But, at a more basic level, it’s difficult because it requires an admission that the way you’ve done things is no longer viable. And, without public admission the old way won’t carry the day, innovation cannot move forward. After the admission there’s no innovation, but it’s one step closer.

Innovation is difficult because it demands new work. But, at a more basic level, it’s difficult because it requires an admission that the way you’ve done things is no longer viable. And, without public admission the old way won’t carry the day, innovation cannot move forward. After the admission there’s no innovation, but it’s one step closer.

After a public admission things must change, a cultural shift must happen for innovation to take hold. And for that, new governance processes are put in place, new processes are created to set new directions and new mechanisms are established to make sure the new work gets done. Those high-level processes are good, but at a more basic level, the objectives of those process areto choose new projects, manage new projects and allocate resources differently. That’s all that’s needed to start innovation work.

But how to choose projects to move the company toward innovation? What are the decision criteria? What is the system to collect the data needed for the decisions? All these questions must be answered and the answers are unique to each company. But for every company, everything starts with a top line growth objective, which narrows to an approach based on an industry, geography or product line, which then further necks down to a new set of projects. Still no innovation, but there are new projects to work on.

The objective of the new projects is to deliver new usefulness to the customer, which requires new technologies, new products and, possibly, new business models. And with all this newness comes increased uncertainty, and that’s the rub. The new uncertainty requires a different approach to project management, where the main focus moves from execution of standard tasks to fast learning loops. Still no innovation, but there’s recognition the projects must be run differently.

Resources must be allocated to new projects. To free up resources for the innovation work, traditional projects must be stopped so their resources can flow to the innovation work. (Innovation work cannot wait to hire a new set of innovation resources.) Stopping existing projects, especially pet projects, is a major organizational stumbling block, but can be overcome with a good process. And once resources are allocated to new projects, to make sure the resources remain allocated, a separate budget is created for the innovation work. (There’s no other way.) Still no innovation, but there are people to do the innovation work.

The only thing left to do is the hardest part – to start the innovation work itself. And to start, I recommend the IBE (Innovation Burst Event). The IBE starts with a customer need that is translated into a set of design challenges which are solved by a cross-functional team. In a two-day IBE, several novel concepts are created, each with a one page plan that defines next steps. At the report-out at the end of the second day, the leaders responsible for allocating the commercialization resources review the concepts and plans and decide on next steps. After the first IBE, innovation has started.

There’s a lot of work to help the organization understand why innovation must be done. And there’s a lot of work to get the organization ready to do innovation. Old habits must be changed and old recipes must be abandoned. And once the battle for hearts and minds is won, there’s an equal amount of work to teach the organization how to do the new innovation work.

It’s important for the organization to understand why innovation is needed, but no customer value is delivered and no increased sales are booked until the organization delivers a commercialized solution.

Some companies start innovation work without doing the work to help the organization understand why innovation work is needed. And some companies do a great job of communicating the need for innovation and putting in place the governance processes, but fail to train the organization on how to do the innovation work.

Truth is, you’ve got to do both. If you spend time to convince the organization why innovation is important, why not get some return from your investment and teach them how to do the work? And if you train the organization how to do innovation work, why not develop the up-front why so everyone rallies behind the work?

Why isn’t enough and how isn’t enough. Don’t do one without the other.

Image credit — Sam Ryan

Innovation is about good judgement.

It’s not the tools. Innovation is not hampered by a lack of tools (See The Innovator’s Toolkit for 50 great ones.), it’s hampered because people don’t know how to start. And it’s hampered because people don’t know how to choose the right tool for the job. How to start? It depends. If you have a technology and no market there are a set of tools to learn if there’s a market. Which tool is best? It depends on the context and learning objective. If you have a market and no technology there’s a different set of tools. Which tool is best? You guessed it. It depends on the work. And the antidote for ‘it depends’ is good judgement.

It’s not the tools. Innovation is not hampered by a lack of tools (See The Innovator’s Toolkit for 50 great ones.), it’s hampered because people don’t know how to start. And it’s hampered because people don’t know how to choose the right tool for the job. How to start? It depends. If you have a technology and no market there are a set of tools to learn if there’s a market. Which tool is best? It depends on the context and learning objective. If you have a market and no technology there’s a different set of tools. Which tool is best? You guessed it. It depends on the work. And the antidote for ‘it depends’ is good judgement.

It’s not the process. There are at least several hundred documented innovation processes. Which one is best? There isn’t a best one – there can be no best practice (or process) for work that hasn’t been done before. So how to choose among the good practices? It depends on the culture, depends on the resources, depends on company strengths. Really, it depends on good judgment exercised by the project leader and the people that do the work. Seasoned project leaders know the process is different every time because the context and work are different every time. And they do the work differently every time, even as standard work is thrust on them. With new work, good judgement eats standardization for lunch.

It’s not the organizational structure. Innovation is not limited by a lack of novel organizational structures. (For some of the best thinking, see Ralph Ohr’s writing.) For any and all organizational structures, innovation effectiveness is limited by people’s ability to ride the waves and swim against the organizational cross currents. In that way, innovation effectiveness is governed by their organizational good judgement.

Truth is, things have changed. Gone are the rigid, static processes. Gone are the fixed set of tools. Gone are the black-and-white, do-this-then-do-that prescriptive recipes. Going forward, static must become dynamic and rigid must become fluid. One-size-fits-all must evolve into adaptable. But, fortunately, gone are the illusions that the dominant player is too big to fail. And gone are the blinders that blocked us from taking the upstarts seriously.

This blog post was inspired by a recent blog post by Paul Hobcraft, a friend and grounded innovation professional. For a deeper perspective on the ever-increasing complexity and dynamic nature of innovation, his post is worth the read.

After I read Paul’s post, we talked about the import role judgement plays in innovation. Though good judgement is not usually called out as an important factor that governs innovation effectiveness, we think it’s vitally important. And, as the pressure increases to deliver tangible innovation results, its importance will increase.

Some open questions on judgement: How to help people use their judgement more effectively? How to help them use it sooner? How to judge if someone has the right level of good judgement?

Image credit – Michael Coghlan

What’s an innovator to do?

Disruption, as a word, doesn’t tell us what to do or how to do it. Disruption, as a word, it’s not helpful and should be struck from the innovation lexicon. But without the word, what’s an innovator to do?

Disruption, as a word, doesn’t tell us what to do or how to do it. Disruption, as a word, it’s not helpful and should be struck from the innovation lexicon. But without the word, what’s an innovator to do?

If you have a superpower, misuse it. Your brand’s special capability is well known in your industry, but not in others. Thrust your uniqueness into an unsuspecting industry and provide novel value in novel ways. Take it by storm. Contradict the established players. Build momentum quickly and quietly. Create a step function improvement. Create new lines of customer goodness. Do things that haven’t been done. Turn no to yes.

Don’t adapt your special capability, use it as-is. Adaptation is good, but it’s better to flop the whole thing into the new space. Don’t think graft, think transplant. Adaptation brings only continuous improvement. It’s better to serve up your secret sauce uncut and unfiltered because that brings discontinuous improvement.

Know the needs your product fulfills and meet those needs in another industry. Some say it’s better to adapt your product to other industries, and to achieve a reasonable CAGR, adaptation is good. But if you’re looking for an unreasonable CAGR, if you’re looking to stand things on their head, try to use your product as-is. When you can use your product as-is in another industry, you connect dots only you can connect and meet needs in ways only you can. You bring non-intuitive solutions. You violate routines of accepted practice and your trajectory is not limited by the incumbents’ ruts of success. You’ll have a whole new space for yourself. No sharing required.

But how?

Simply and succinctly, define what your product does. Then, make it generic and look to misapply the goodness in a different application. For example, manufacturers of large and expensive furniture wrap their products in huge plastic bags to keep the furniture dry and clean during shipping. Generically, the function becomes: use large plastic bags to temporarily protect large and expensive products from becoming wet. Using that goodness in a new application, people who live in flood areas use the large furniture bags to temporarily protect their cars from water damage. Just before the flood arrives, they drive their cars into large plastic bags and tie them off. The bags keep their car dry when the water comes. Same bag, same goodness, completely unrelated application.

And there’s another way. Your product has a primary function that provides value to your customers. But, there is unrealized value in your product that your existing customers don’t value. For example, if your company has a proprietary process to paint products in a way that results in a high gloss finish, your customers buy your coating because it looks good. But, the coating may also create a hard layer and increase wear resistance that could be important in another application. Because your coating is environmentally friendly and your process is low-cost, new customers may want you to coat their parts so they can be used in a previously non-viable application. There is unrealized value in your products that new customers will pay for.

To see the unrealized value, use the strength-as-a-weakness method. Define two constraints: you must sell to new customers in a new industry and the primary goodness, why people buy your product, must be a weakness. For example, if your product is fast, you’ve got to use unrealized value to sell a slow one. If it’s heavy, the new one must be light. If small, the new one must be large. In that way, you are forced to rely on new lines of goodness and unrealized value to sell your product.

Don’t stop continuous improvement and product adaptation. They’re valuable. But, start some discontinuous improvement, step function increases and purposeful misuse. Keep selling to the same value to the same customers, but start selling to new customers with previously unrealized value that has been hiding quietly in your product for years.

Evolution is good, but exaptation is probably better.

Image credit – Sor Betto

How To Reduce Innovation Risk

The trouble with innovation is it’s risky. Sure, the upside is nice (increased sales), but the downside (it doesn’t work) is distasteful. Everyone is looking for the magic pill to change the risk-reward ratio of innovation, but there is no pill. Though there are some things you can do to tip the scale in your favor.

The trouble with innovation is it’s risky. Sure, the upside is nice (increased sales), but the downside (it doesn’t work) is distasteful. Everyone is looking for the magic pill to change the risk-reward ratio of innovation, but there is no pill. Though there are some things you can do to tip the scale in your favor.

All problems are business problems. Problem solving is the key to innovation, and all problems are business problems. And as companies embrace the triple bottom line philosophy, where they strive to make progress in three areas – environmental, social and financial, there’s a clear framework to define business problems.

Start with a business objective. It’s best to define a business problem in terms of a shortcoming in business results. And the holy grail of business objectives is the growth objective. No one wants to be the obstacle, but, more importantly, everyone is happy to align their career with closing the gap in the growth objective. In that way, if solving a problem is directly linked to achieving the growth objective, it will get solved.

Sell more. The best way to achieve the growth objective is to sell more. Bottom line savings won’t get you there. You need the sizzle of the top line. When solving a problem is linked to selling more, it will get solved.

Customers are the only people that buy things. If you want to sell more, you’ve got to sell it to customers. And customers buy novel usefulness. When solving a problem creates novel usefulness that customers like, the problem will get solved. However, before trying to solve the problem, verify customers will buy what you’re selling.

No-To-Yes. Small increases in efficiency and productivity don’t cause customers to radically change their buying habits. For that your new product or service must do something new. In a No-To-Yes way, the old one couldn’t but the new one can. If solving the problem turns no to yes, it will get solved.

Would they buy it? Before solving, make sure customers will buy the useful novelty. (To know, clearly define the novelty in a hand sketch and ask them what they think.) If they say yes, see the next question.

Would it meet our growth objectives? Before solving, do the math. Does the solution result in incremental sales larger than the growth objective? If yes, see the next question.

Would we commercialize it? Before solving, map out the commercialization work. If there are no resources to commercialize, stop. If the resources to commercialize would be freed up, solve it.

Defining is solving. Up until now, solving has been premature. And it’s still not time. Create a functional model of the existing product or service using blocks (nouns) and arrows (verbs). Then, to create the problem(s), add/modify/delete functions to enable the novel usefulness customers will buy. There will be at least one problem – the system cannot perform the new function. Now it’s time to take a deep dive into the physics and bring the new function to life. There will likely be other problems. Existing functions may be blocked by the changes needed for the new function. Harmful actions may develop or some functions will be satisfied in an insufficient way. The key is to understand the physics in the most complete way. And solve one problem at a time.

Adaptation before creation. Most problems have been solved in another industry. Instead of reinventing the wheel, use TRIZ to find the solutions in other industries and adapt them to your product or service. This is a powerful lever to reduce innovation risk.

There’s nothing worse than solving the wrong problem. And you know it’s the wrong problem if the solution doesn’t: solve a business problem, achieve the growth objective, create more sales, provide No-To-Yes functionality customers will buy, and you won’t allocate the resources to commercialize.

And if the problem successfully runs the gauntlet and is worth solving, spend time to define it rigorously. To understand the bedrock physics, create a functional of the system, add the new functionality and see what breaks. Then use TRIZ to create a generic solution, search for the solution across other industries and adapt it.

The key to innovation is problem solving. But to reduce the risk, before solving, spend time and energy to make sure it’s the right problem to solve.

It’s far faster to solve the right problem slowly than to solve the wrong one quickly.

Image credit – Kate Ter Haar

Before you can make a million, you’ve got to make the first one.

With process improvement, the existing process is refined over time. With innovation, the work is new. You can’t improve a process that does not yet exist. Process creation, yes. Process improvement, no.

With process improvement, the existing process is refined over time. With innovation, the work is new. You can’t improve a process that does not yet exist. Process creation, yes. Process improvement, no.

Standard work, where the sequence of process steps has proven successful, is a pillar of the manufacturing mindset. In manufacturing, if you’re not following standard work, you’re not doing it right. But with innovation, when the work is done for the first time, there can be no standard work. In that way, if you’re following the standard work paradigm, you are not doing innovation.

In a well-established manufacturing process, problems are tightly scoped and constrained. There can be several ways to solve it and one of the ways is usually better than the others. Teams are asked to solve the problem three or four ways and explain the rationale for choosing one solution over the other. With innovation it’s different. There may not be a solution, never mind three. With innovation, it’s one-in-a-row solution. And the real problem is to decide which problem to solve. If you’re asked to use Fishbone diagrams to solve the problem three or four ways, you’re not doing innovation. Solve it one way, show a potential customer and decide what to do next.

With manufacturing and product development, it’s all about Gantt charts and hitting dates. The tasks have a natural precedence and all of them have been done before. There are branches in the plan, but behind them is clear if-then logic. With innovation, the first task is well-defined. And the second task – it depends on the outcome of the first. And completion dates? No way. If you can predict the completion date, you’re not doing innovation. And if you’re asked for a fully built-out Gantt chart, you’re in trouble because that’s a misguided request.

Systems in manufacturing can be complicated, with lots of moving parts. And the problems can be complicated. But given enough time, the experts can methodically figure it out. But with innovation, the systems can be complex, meaning they are not predictable. Sometimes parts of the system interact strongly with other parts and sometimes they don’t interact at all. And it’s not that they do one or the other, it’s that they do both. It’s like they have a will of their own, and, sometimes, they have a bad attitude. And if it’s a new system, even the basic rules of engagement are unknown, never mind the changing strength of the interactions. And if the system is incomplete and you don’t know it, linear thinking of the experts can’t solve it. If you’re using linear problem solving techniques, you’re not doing innovation.

Manufacturing is about making one thing a million times. Innovation is about choosing among the million possibilities and making one-in-a-row, and then, after the bugs are worked out, making the new thing a million times. But one-in-a-row must come first. If you can’t do it once, you can’t do it a million times, even with process improvement, standard work, Gantt charts and Fishbone diagrams.

Image credit jacinta lluch valero

See differently to solve differently.

There are many definitions for creativity and innovation, but none add meaningfully to how the work is done. Though it’s clear why the work is important – creativity and innovation underpin corporate prosperity and longevity – it’s especially helpful to know how to do it.

There are many definitions for creativity and innovation, but none add meaningfully to how the work is done. Though it’s clear why the work is important – creativity and innovation underpin corporate prosperity and longevity – it’s especially helpful to know how to do it.

At the most basic level, creativity and innovation are about problem solving. But it’s a special flavor of problem solving. Creativity and innovation are about problems solving new problems in new ways. The glamorous part is ‘solving in new ways’ and the important part is solving new problems.

With continuous improvement the same problems are solved over and over. Change this to eliminate waste, tweak that to reduce variation, adjust the same old thing to make it work a little better. Sure, the problems change a bit, but they’re close cousins to the problems to the same old problems from last decade. With discontinuous improvement (which requires high levels of creativity and innovation) new problems are solved. But how to tell if the problem is new?

Solving new problems starts with seeing problems differently.

Systems are large and complicated, and problems know how to hide in the nooks and crannies. In a Where’s Waldo way, the nugget of the problem buries itself in complication and misuses all the moving parts as distraction. Problems use complication as a cloaking mechanism so they are not seen as problems, but as symptoms.

Telescope to microscope. To see problems differently, zoom in. Create a hand sketch of the problem at the microscopic level. Start at the system level if you want, but zoom in until all you see is the problem. Three rules: 1. Zoom in until there are only two elements on the page. 2. The two elements must touch. 3. The problem must reside between the two elements.

Noun-verb-noun. Think hammer hits nail and hammer hits thumb. Hitting the nail is the reason people buy hammers and hitting the thumb is the problem.

A problem between two things. The hand sketch of the problem would show the face of the hammer head in contact with the surface of the thumb, and that’s all. The problem is at the interface between the face of the hammer head and the surface of the thumb. It’s now clear where the problem must be solved. Not where the hand holds the shaft of the hammer, not at the claw, but where the face of the hammer smashes the thumb.

Before-during-after. The problem can be solved before the hammer smashes the thumb, while the hammer smashes the thumb, or after the thumb is smashed. Which is the best way to solve it? It depends, that’s why it must be solved at the three times.

Advil and ice. Solving the problem after the fact is like repair or cleanup. The thumb has been smashed and repercussions are handled in the most expedient way.

Put something between. Solving the problem while it happens requires a blocking or protecting action. The hammer still hits the thumb, but the protective element takes the beating so the thumb doesn’t.

Hand in pocket. Solving the problem before it happens requires separation in time and space. Before the hammer can smash the thumb it is moved to a safe place – far away from where the hammer hits the nail.

Nail gun. If there’s no way for the thumb to get near the hammer mechanism, there is no problem.

Cordless drill. If there are no nails, there are no hammers and no problem.

Concrete walls. If there’s no need for wood, there’s no need for nails or a hammer. No hammer, no nails, no problem.

Discerning between symptoms and problems can help solve new problems. Seeing problems at the micro level can result in new solutions. Looking closely at problems to separate them time and space can help see problems differently.

Eliminating the tool responsible for the problem can get rid of the problem of a smashed thumb, but it creates another – how to provide the useful action of the driven nail. But if you’ve been trying to protect thumbs for the last decade, you now have a chance to design a new way to fasten one piece of wood to another, create new walls that don’t use wood, or design structures that self-assemble.

Image credit – Rodger Evans

Put Yourself Out There

If you put yourself out there and it doesn’t go as you expect, don’t get down. All you are responsible for is your effort and your intentions. You’re not responsible for the outcome. Intentions don’t drive outcomes. In fact, be prepared for your work to bring out the opposite of your intentions.

If you put yourself out there and it doesn’t go as you expect, don’t get down. All you are responsible for is your effort and your intentions. You’re not responsible for the outcome. Intentions don’t drive outcomes. In fact, be prepared for your work to bring out the opposite of your intentions.

If you put yourself out there and it goes poorly, don’t judge yourself negatively. Sometimes, things go that way. It’s not a problem, unless you make it one. So, don’t make it one. Just put yourself out there.

The clothes don’t get clean without an agitator. Hold onto that, and put yourself out there.

How do you know you’ve put yourself out there? The status quo is angry with you. The people in power want you to stop. The organization tries to scuttle your work. And the people that know the truth take you out to lunch.

If you put yourself out there and your message is met with 100% agreement, you didn’t put yourself out there. You may have stepped outside the lines, but you didn’t put your whole self on the line. You didn’t splash everyone with a full belly flop. There wasn’t enough sting and your belly isn’t red enough.

You won’t get it right, but put yourself out there anyway. You can’t predict the outcome, but take a run at the status quo. You don’t know how it will turn out, but that’s not a reason to hold back, it’s objective evidence it’s time to take a run at it.

Don’t put yourself out there because it’s the right thing to do, put yourself out there because you have an emotional connection. Put yourself out there because it’s time to put yourself out there. Put yourself out there because you don’t know what else to do.

Be prepared to be misunderstood, but put yourself out there. Expect to be laughed at and talked about behind your back, but put yourself out there. And expect there will be one or two people who will have your back. You know who they are.

No sense holding back. Get over the fear and put yourself out there.

The only one holding you back is you.

Image credit – Mark Bonica

Success – the Enemy of New Work

Success is the enemy of new work. Past success blocks new work out of fear it will jeopardize future success, and future success blocks new work out of fear future success will actually come to be.

Success is the enemy of new work. Past success blocks new work out of fear it will jeopardize future success, and future success blocks new work out of fear future success will actually come to be.

Either way you look at it, success gets in the way of doing new work.

Success itself has no power to block new work. To generate its power, past success creates the fear of loss in the people doing today’s work. And their fear causes them to block new work. When we did A we got success, and now you are trying to do B. B is not A, and may not bring success. I will resist B out of fear of losing the goodness of past success.

As a blocking agent, future success is more ethereal and more powerful because it prevents new work from starting. Future success causes our minds to project the goodness and glory the new work could bring and because our small sense of self doesn’t think we’re worthy, we never start. Where past success creates an enemy in the status quo, future success creates an enemy within ourselves.

But if we replace fear with learning, the game changes.

I’m not trying to displace our past success, I’m trying to learn if we can use it as springboard and back flip into the deep end of our future success. If it works, our learning will refine today’s success and inform tomorrow’s. If it doesn’t work, we’ll learn what doesn’t work and try something else. But not to worry, we’ll make small bets and create big learning. That way when we jump in the puddle, the splash will be small. And if the water’s cold, we’ll stop. But if it’s warm, we’ll jump into a bigger puddle. And maybe we’ll jump together. What do you think? Will you help me learn?

Yes, it’s scary to think about running this small experiment. Not because it won’t work, but because it might. If we learn this could work it would be a game-changer for the company and I’m afraid I’m not worthy of the work. Can you help me navigate this emotional roller coaster? Can you help me learn if this will work? Can you review the results privately and help me learn what’s going on? If we don’t learn how to do it, our competitors will. Can you help me start?

Success blocks, but it also pays the bills. And, hopefully it’s always part of the equation. But there are things we can do to take the edge of its blocking power. Acknowledge that new work is scary and focus on learning. Learning isn’t threatening, and it moves things forward. Show results and ask for comments from people who created past success. Over time, they’ll become important advocates. And acknowledge to yourself that new work creates internal fear, and acknowledge the best way to push through fear is to learn.

Be afraid, make small bets and learn big.

Image credit – Andy Morffew

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski