A Barometer for Uncertainty

Novelty, or newness, can be a great way to assess the status of things. The level of novelty is a barometer for the level of uncertainty and unpredictability. If you haven’t done it before, it’s novel and you should expect the work to be uncertain and unpredictable. If you’ve done it before, it’s not novel and you should expect the work to go as it did last time. But like the barometer that measures a range of atmospheric pressures and gives an indication of the weather over the next hours, novelty ranges from high to low in small increments and so does the associated weather conditions.

Novelty, or newness, can be a great way to assess the status of things. The level of novelty is a barometer for the level of uncertainty and unpredictability. If you haven’t done it before, it’s novel and you should expect the work to be uncertain and unpredictable. If you’ve done it before, it’s not novel and you should expect the work to go as it did last time. But like the barometer that measures a range of atmospheric pressures and gives an indication of the weather over the next hours, novelty ranges from high to low in small increments and so does the associated weather conditions.

Barometers have a standard scale that measures pressure. When the summer air is clear and there are no clouds, the atmospheric pressure is high and on the rise and you should put on sun screen. When it’s hurricane season and super-low system approaches, the drops to the floor and you should evacuate. The nice thing about barometers is they are objective. On all continents, they can objectively measure the pressure and display it. No judgement, just read the scale. And regardless of the level of pressure and the number of times they measure it, the needle matches the pressure. No Kentucky windage. But novelty isn’t like that.

The only way to predict how things will go based on the level of novelty is to use judgement. There is no universal scale for novelty that works on all projects and all continents. Evaluating the level of novelty and predicting how the projects will go requires good judgement. And the only way to develop good judgment is to use bad judgment until it gets better.

All novelty isn’t created equal. And that’s the trouble. Some novelty has a big impact on the weather and some doesn’t. The trick is to know the difference. And how to tell the difference? If when you make a change in one part of the system (add novelty) and the novelty causes a big change in the function or operation of the system, that novelty is important. The system is telling you to use a light hand on the tiller. If the novelty doesn’t make much difference in system performance, drive on. The trick is to test early and often – simple tests that give thumbs-up or thumbs-down results. And if you try to run a test and you can’t get the test to run at all, there’s a hurricane is on the horizon.

When the work is new, you don’t really know which novelty will bite you. But there’s one rule: all novelty will bite you until proven otherwise. Make a list of the novel elements of the and test them crudely and quickly.

Allocating resources as if people and planet mattered.

Business is about allocating resources to achieve business objectives. And for that, the best place to start is to define the business objectives.

Business is about allocating resources to achieve business objectives. And for that, the best place to start is to define the business objectives.

First – what is the timeframe of the business objectives? Well, there are three – short, medium and long. Short is about making payroll, shipping this month’s orders and meeting this year’s sales objectives. Long is about the existence of the company over the next decade and happiness of the people that do the work along the way. And medium – the toughest – is in-between. It’s neither short nor long but bound by both.

Second – define business objectives within the three types: people, planet and profit.

People. Short term: pay them so they can eat, pay the mortgage and fund their retirement, provide healthcare, provide a safe workplace, give them work that fits their strengths and give them time to improve their community. Medium: pay them so they can provide for their family and fund their retirement, provide healthcare, provide a safer workplace, give them work that requires them to grow their strengths and give them time to become community leaders. Long: pay them so they can pay for their kids’ college and know they can safely retire, provide the safest workplace, let them choose their own work, and give them time to grow the next community leaders. And make it easy.

Planet. Short term: teach Life Cycle Assessment, Buddhist Economics and TRIZ and create business metrics for them to flourish. Medium: move from global sourcing to local sourcing, move to local production, move from business models based on non-renewable resources to renewable resources. Long: create new business models that are resource neutral. Longer: create business models that generate excess resources. Longest: teach others.

Profit. Short, medium and long – focus on people and planet and the profits will come. But also focus on creating new value for new customers.

For business objectives, here’s the trick on timeframe – always work short term, always work long term and prioritize medium term.

And for the three types of business objectives, focus on people, planet and creating new value for new customers. Profits are a result.

Image credit – magnetismus

A three-pronged approach for making progress

When you’re looking to make progress, the single most important skill is to see waiting as waiting.

The first place to look for waiting is the queue in front of a shared resource. Like taking a number at the deli, you queue up behind the work that got there first and your work waits its turn. And when the situation turns bad, prioritization meeting spring up to argue about the importance of one bit of work over another. Those meetings are a sure-fire sign of ineffectiveness. When these meetings spring up, it’s time to increase capacity of the shared resource to stop waiting and start making progress.

Another place to look for waiting is the process to schedule a meeting with high-level leaders. Their schedules are so full (efficiency over effectiveness) the next open meeting slot is next month. Let me translate – “As a senior leader and decision maker, I want you to delay the business-critical project until I carve out an hour so you can get me up to speed and I can tell you what to do.” The best project managers don’t wait. They schedule the meeting three weeks from now, make progress like their hair is on fire and provide a status update when the meeting finally happens. And the smartest leaders thank the project managers for using their discretion and good judgment.

A variant of the wait-for-the-most-important-leader theme is the never-ending-series-of-meetings-where-no-decisions-are-made scenario. The classic example of this unhealthy lifestyle is where a meeting to make a decision spawns a never-ending series of weekly meetings with 12 or more regular attendees where the initial agenda of making a decision death spirals into an ever-changing, and ultimately disappearing agenda. Everyone keeps meeting, but no one remembers why. And the decision is never made. The saddest part is that no one remembers that project is blocked by the non-decision.

The first place to look for waiting is the queue in front of a shared resource. Like taking a number at the deli, you line up behind the work that got there first and your work waits its turn. And when the situation turns bad, prioritization meeting spring up to argue about the importance of one bit of work over another. Those meetings are a sure-fire sign of ineffectiveness. It’s time to increase capacity of the shared resource to stop waiting and start making progress.

And the deadliest waiting is the waiting that we no longer see as waiting. The best example of this crippling non-waiting waiting is when we cannot work the critical path and, instead, we work on a task of secondary importance. We kid ourselves into thinking we’re improving efficiency when, in fact, we’re masking the waiting and enabling the poor decision making that starved the project of the resources it needs to work the critical path. Whether you work a non-critical path task or not, when you can’t work the critical path for a week, you delay project completion by a week. That’s a rule.

Instead of spending energy working a non-critical path task, it’s better for everyone if you do nothing. Sit at your desk and play solitaire on your computer or surf the web. Do whatever it takes for your leader to recognize you’re not making progress. And when your leader tries to chastise you, tell them to do their job and give you what you need to work the critical path.

There’s two types of work – value-added work and non-value-added work. Value-added work happens when you complete a task on the critical path. Non-value-added work happens when you wait, when you do work that’s not on the critical path, when you get ready to do work and when you clean up after doing work. In most processes, the ratio of non-value-added to value-added work is 20:1 to 200:1. Meaning, for every hour of value-added work there are twenty to two hundred hours of non-value-added work.

If you want to make progress, don’t improve how you do your value-added work. Instead, identify the non-value-added work you can stop and stop it. In that way, without changing how you do an hour long value-added task, you can eliminate twenty to two hundred hours wasted effort.

Here’s the three-pronged approach for making progress:

Prong one – eliminate waiting. Prong two – eliminate waiting. Prong three – eliminate waiting.

Image credit João Lavinha

Additive Manufacturing’s Holy Grail

The holy grail of Additive Manufacturing (AM) is high volume manufacturing. And the reason is profit. Here’s the governing equation:

The holy grail of Additive Manufacturing (AM) is high volume manufacturing. And the reason is profit. Here’s the governing equation:

(Price – Cost) x Volume = Profit

The idea is to sell products for more than the cost to make them and sell a lot of them. It’s an intoxicatingly simple proposition. And as long as you look only at the volume – the number of products sold per year – life is good. Just sell more and profits increase. But for a couple reasons, it’s not that simple. First, volume is a result. Customers buy products only when those products deliver goodness at a reasonable price. And second, volume delivers profit only when the cost is less than the price. And there’s the rub with AM.

Here’s a rule – as volume increases, the cost of AM is increasingly higher than traditional manufacturing. This is doubly bad news for AM. Not only is AM more expensive, its profit disadvantage is particularly troubling at high volumes. Here’s another rule – if you’re looking to AM to reduce the cost of a part, look elsewhere. AM is not a bottom-feeder technology.

If you want to create profits with AM, use it to increase price. Use it to develop products that do more and sell for more. The magic of AM is that it can create novel shapes that cannot be made with traditional technologies. And these novel shapes can create products with increased function that demand a higher price. For example, AM can create parts with internal features like serpentine cooling channels with fine-scale turbulators to remove more heat and enable smaller products or products that weigh less. Lighter automobiles get better fuel mileage and customers will pay more. And parts that reduce automobile weight are more valuable. And real estate under the hood is at a premium, and a smaller part creates room for other parts (more function) or frees up design space for new styling, both of which demand a higher price.

Now, back to cost. There’s one exception to cost rule. AM can reduce total product cost if it is used to eliminate high cost parts or consolidate multiple parts into a single AM part. This is difficult to do, but it can be done. But it takes some non-trivial cost analysis to make the case. And, because the technology is relatively new, there’s some aversion to adopting AM. An AM conversion can require a lot of testing and a significant cost reduction to take the risk and make the change.

To win with AM, think more function AND consolidation. More (or new) function to support a higher price (and increase volume) and reduced cost to increase profit per part. Don’t do one or the other. Do both. That’s what GE did with its AM fuel nozzle in their new aircraft engines. They combined 20 parts into a single unit which weighed 25 percent less than a traditional nozzle and was more than five times as durable. And it reduced fuel consumption (more function, higher price).

AM is well-established in prototyping and becoming more established in low-volume manufacturing. The holy grail for AM – high volume manufacturing – will become a broad reality as engineers learn how to design products to take advantage of AM’s unique ability to make previously un-makeable shapes and learn to design for radical part consolidation.

More function AND radical part consolidation. Do both.

Image credit – Les Haines

Make It Easy

When you push, you make it easy for people resist. When you break trail, you make it easy for them to follow.

When you push, you make it easy for people resist. When you break trail, you make it easy for them to follow.

Efficiency is overrated, especially when it interferes with effectiveness. Make it easy for effectiveness to carry the day.

You can push people off a cliff or build them a bridge to the other side. Hint – the bridge makes it easy.

Even new work is easy when people have their own reasons for doing it.

Making things easier is not easy.

Don’t tell people what to do. Make it easy for them to use their good judgement.

Set the wrong causes and conditions and creativity screeches to a halt. Set the right ones and it flows easily. Creativity is a result.

Don’t demand that people pull harder, make it easier for them to pull in the same direction.

Activity is easy to demonstrate and progress isn’t. Figure out how to make progress easier to demonstrate.

The only way to make things easier is to try to make them easier.

Image credit – Richard Hurd

The Power of Surprise

There’s disagreement on what is creative, innovative and disruptive. And there is no set of hard criteria to sort concepts into the three categories. Stepping back a bit, a lesser but still important sorting is an in-or-out categorization. Though not as good as discerning among the three, it is useful to decide if a new concept is in (one of the three) or out (not).

There’s disagreement on what is creative, innovative and disruptive. And there is no set of hard criteria to sort concepts into the three categories. Stepping back a bit, a lesser but still important sorting is an in-or-out categorization. Though not as good as discerning among the three, it is useful to decide if a new concept is in (one of the three) or out (not).

The closest thing to an acid test is assessment of the emotional response generated by a new concept. Here are some responses that I consider tell-tail signs of powerful ideas/concepts worthy of the descriptors creative, innovative, or disruptive.

When first shown, a prototype creates fear and defensiveness. The fear signals that the prototype threatens the status quo and defensiveness is objective evidence of the fear.

When first explained, a new concept creates anger and aggression. Because the concept doesn’t play by the rules, it disrespects everything holy, and the unfairness spawns indigence.

After some time, the dismissive comments about the new prototype fade and turn to discussions colored by deep sadness as the gravity of the situation hits home.

But the best leading indicator is surprise. When a test result doesn’t match your expectations, it generates surprise. And since your expectations are built on your mental models, surprising concepts contradict your mental models. And since your mental models are formed by successful experiences, prototypes that create surprise violate previous success.

If you’re surprised by a new concept, it’s worth a deeper look. If you’re not surprised, move on.

If you’re not tolerant of surprise, you should be. And if you are tolerant of surprise, it’s time to become fervent.

Image credit – Raul Pop

The one good way to change behavior.

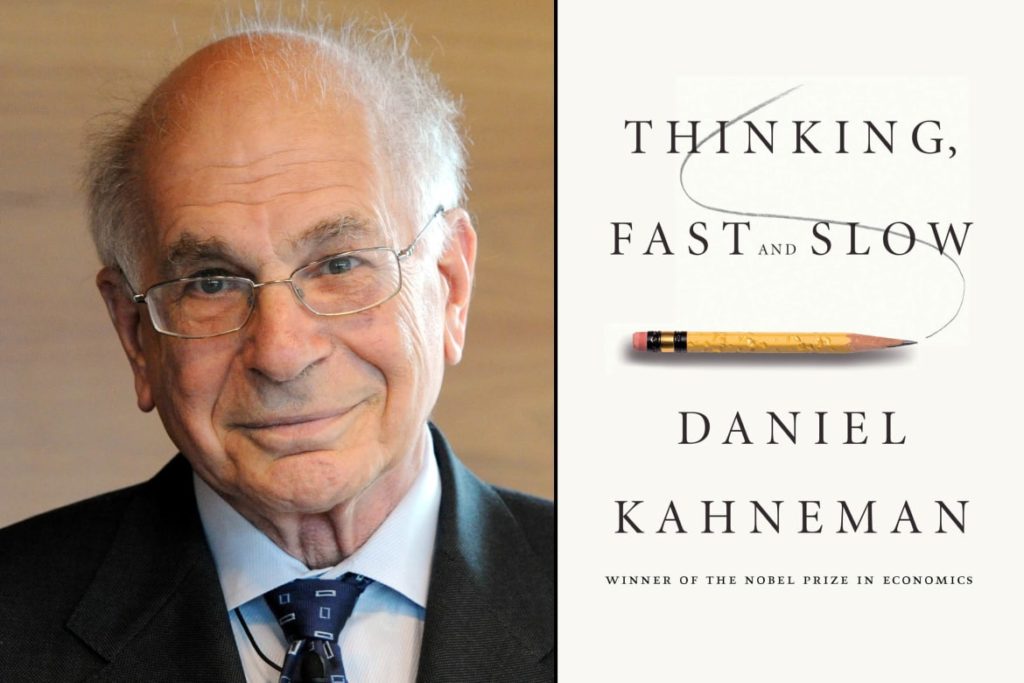

There’s one good way to change behavior. But don’t take my word for it, take Daniel Kahneman’s, psychologist who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences. In Freakonomics Radio’s podcast How to Launch a Behavioral Change Revolution, Kahneman explains how to achieve change in behavior. His explanation is short [30:35 – 35:21] and good.

There’s one good way to change behavior. But don’t take my word for it, take Daniel Kahneman’s, psychologist who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences. In Freakonomics Radio’s podcast How to Launch a Behavioral Change Revolution, Kahneman explains how to achieve change in behavior. His explanation is short [30:35 – 35:21] and good.

Kahneman describes a theory of Kurt Lewin, his academic grandfather, where behavior is an equilibrium, a balance between driving forces that push for change and restraining forces that hold back change. Kahneman goes on to describe Lewin’s insight. “Lewin’s insight was that if you want to achieve change in behavior, there is one good way to do it and one bad way. The good way is by diminishing restraining forces, not by increasing the driving forces. That turns out to be profoundly non-intuitive.”

Usually, when we want someone to change, we push them in the direction we want them to go. Kahneman says this approach is natural, but ineffective. He offers a different approach – “Instead of asking how can I get him or her to do it, it starts with a question of why isn’t she doing it already? Go one-by-one, systematically, and you ask ‘What can I do to make it easier for that person to move?’”

What would happen if instead of pushing someone to change, you understand what’s in the way and eliminated the restraining force? I don’t know, but I’m going to give it a try.

Kahneman goes on to describe how to make things easier for a person to move. He says “…the way to make things easier is almost always by controlling the individual’s environment…by just making it easier.” Sounds pretty simple – change people’s environment to make it easier for them to move toward the desired behavior. But, we don’t do it that way.

Kahneman gives more detail. “Are there incentives that work against it? Let’s change the incentives.” And then he gives a simple example. “I want to influence B, but there is A in the background and it’s A who is a restraining force on B, let’s work on A, not on B.”

I urge you to listen to the short segment to hear Kahneman’s words for yourself. His ideas really hit home when you hear them from him.

How to wallow in the mud of uncertainty.

Creativity and innovation are dominated by uncertainty. And in the domain of uncertainty, not only are the solutions unknown, the problems are unknown. And yet, we still try to use the tried-and-true toolbox of certainty even after it’s abundantly clear those wrenches don’t fit.

Creativity and innovation are dominated by uncertainty. And in the domain of uncertainty, not only are the solutions unknown, the problems are unknown. And yet, we still try to use the tried-and-true toolbox of certainty even after it’s abundantly clear those wrenches don’t fit.

When wallowing in the mud of uncertainty and company leaders ask, “When will you be done?”, the only real answer is a description of the next thing you’ll try to learn. “We will learn if Step 1 is possible.” And then the predicted response, “Well, when will you be done with that?” The only valid response is, “It depends.” Though truthful, this goes over like a lead balloon. And the dialog continues – “Okay, then, what is Step 2?” The unpalatable answer, “It depends. If Step 1 is successful, we’ll move onto Step 2, but if Step 1 is unsuccessful, we’ll step back and regroup.” This, too, though truthful, is unsatisfactory.

When doing creative work, there’s immense pressure to be done on time. But, that pressure is inappropriate. Yes, there can be pressure to learn quickly and effectively, but the expectation to be done within an arbitrary timeline is ludicrous. Managers don’t know this, but when they demand a completion date for a task that has never been done before, the people doing the creative work know the manager doesn’t know what they’re doing. They won’t tell the manager what they think, but they definitely think it. And when pushed to give a completion date, they’ll give one, knowing full well the predicted date is just as arbitrary as the manager’s desired timeline.

But learning objectives can create common ground. Starting with “We want to learn if…”, learning objectives define what the project team must learn. Though there’s no agreement on when things will be completed, everyone can agree on the learning objectives. And with clearly defined learning objectives and measurable definitions of success, the project can move forward with consensus. There is still consternation over the lack of hard deadlines for the learning objectives, but there is agreement on the sequence of events, tests protocols or analyses that will be carried out to learn what must be learned.

Two rules to live by: If you know when you’ll be done, you’re not doing innovation. And if no one is surprised by the solution, you’re not doing creative work.

Image credit – Michael Carian

To improve productivity, it’s time to set limits.

The race for productivity is on. And to take productivity to the next level, set limits.

The race for productivity is on. And to take productivity to the next level, set limits.

To reduce the time wasted by email, limit the number of emails a person can send to ten emails per day. Also, eliminate the cc function. If you send a single email to ten people, you’re done for the day. This will radically reduce the time spent writing emails and reduce distraction as fewer emails will arrive. But most importantly, it will help people figure out which information is most important to communicate and create a natural distillation of information. Lastly, limit the number of word in an email to 100. This will shorten the amount of time to read emails and further increase the density of communications.

If that doesn’t eliminate enough waste, limit the number of emails a person can read to ten emails per day. Provide the subject of the email and the sender, but no preview. Use the subject and sender to decide which emails to read. And, yes, responding to an email counts against your daily sending quota of ten. The result is further distillation of communication. People will take more time to decide which emails to read, but they’ll become more productive through use of their good judgement.

Limit the number of meetings people can attend to two per day and cap the maximum meeting length to 30 minutes. The attendees can use the meeting agenda, meeting deliverables and decisions made at the meeting to decide which meetings to attend. This will cause the meeting organizers to write tight, compelling agendas and make decisions at meetings. Wasteful meetings will go away and productivity will increase.

To reduce waiting, limit the number of projects a person can work on to a single project. Set the limit to one. That will force people to chase the information they need instead of waiting. And if they can’t get what they need, they must wait. But they must wait conspicuously so it’s clear to leaders that their people don’t have what they need to get the project done. The conspicuous waiting will help the leaders recognize the problem and take action. There’s a huge productivity gain by preventing people from working on things just to look busy.

Though harsh, these limits won’t break the system. But they will have a magical influence on productivity. I’m not sure ten is the right number of emails or two is the right number of meetings, but you get the idea – set limits. And it’s certainly possible to code these limits into your email system and meeting planning system.

Not only will productivity improve, happiness will improve because people will waste less time and get to use their judgement.

Everyone knows the systems are broken. Why not give people the limits they need and make the productivity improvements they crave?

Image credit – XoMEoX

Innovation in three words – Solve Different Problems

With innovation, novel solutions pay the bills – a new solution provides new value for the customer and the customer buys it from you. The trick, however, is to come up with novel solutions. To improve the rate and quality of novel solutions, there’s usually a focus on new tools, new problem-solving methods and training on both. The idea is get better at moving from problem to solution. There’s certainly room for improvement in our problem-solving skills, but I think the pot of gold is hidden elsewhere.

With innovation, novel solutions pay the bills – a new solution provides new value for the customer and the customer buys it from you. The trick, however, is to come up with novel solutions. To improve the rate and quality of novel solutions, there’s usually a focus on new tools, new problem-solving methods and training on both. The idea is get better at moving from problem to solution. There’s certainly room for improvement in our problem-solving skills, but I think the pot of gold is hidden elsewhere.

Because novel solutions reside in uncharted design space, it follows that novel solutions will occur more frequently if the problem-solvers are pointed toward new design space. And to make sure they don’t solve in the tired, old design space of success, constraints are used to wall it off. Rule 1 – point the solvers toward new design space. Rule 2 – wall off the over-planted soil of success.

The best way to guide the problems solvers toward fertile design space is to create different problems for them to solve. And this guide-the-solvers thinking is a key to the success of the IBE (Innovation Burst Event), where Design Challenges are created in a way that forces the solvers from the familiar. And it’s these Design Challenges that ARE the new problems that bring the new solutions. And to wall off old design space, the Design Challenges use creatively curated constraints to make it abundantly clear that old solutions won’t cut it.

Before improving the back-end problem solving process, why not change the front- end problem selecting process?

Chose to solve different problems, then learn to solve them differently.

Image credit – Rajarshi MITRA

The Additive Manufacturing Maturity Model

Additive Manufacturing (AM) is technology/product space with ever-increasing performance and an ever-increasing collection of products. There are many different physical principles used to add material and there are a range of part sizes that can be made ranging from micrometers to tens of meters. And there is an ever-increasing collection of materials that can be deposited from water soluble plastics to exotic metals to specialty ceramics.

Additive Manufacturing (AM) is technology/product space with ever-increasing performance and an ever-increasing collection of products. There are many different physical principles used to add material and there are a range of part sizes that can be made ranging from micrometers to tens of meters. And there is an ever-increasing collection of materials that can be deposited from water soluble plastics to exotic metals to specialty ceramics.

But AM tools and technologies don’t deliver value on their own. In order to deliver value, companies must deploy AM to solve problems and implement solutions. But where to start? What to do next? And how do you know when you’ve arrived?

To help with your AM journey, below a maturity model for AM. There are eight categories, each with descriptions of increasing levels of maturity. To start, baseline your company in the eight categories and then, once positioned, look to the higher levels of maturity for suggestions on how to move forward.

For a more refined calibration, a formal on-site assessment is available as well as a facilitated process to create and deploy an AM build-out plan. For information on on-site assessment and AM deployment, send me a note at mike@shipulski.com.

Execution

- Specify AM machine – There a many types of AM machines. Learn to choose the right machine.

- Justify AM machine – Define the problem to be solved and the benefit of solving it.

- Budget for AM machine – Find a budget and create a line item.

- Pay for machine – Choose the supplier and payment method – buy it, rent to own, credit card.

- Install machine – Choose location, provide necessary inputs and connectivity

- Create shapes/add material – Choose the right CAD system for the job, make the parts.

- Create support/service systems – Administer the job queue, change the consumables, maintenance.

- Security – Create a system for CAD files and part files to move securely throughout the organization.

- Standardize – Once the first machines are installed, converge on a small set of standard machines.

- Teach/Train – Create training material for running AM machine and creating shapes.

Solution

- Copy/Replace – Download a shape from the web and make a copy or replace a broken part.

- Adapt/Improve – Add a new feature or function, change color, improve performance.

- Create/Learn – Create something new, show your team, show your customers.

- Sell Products/Services – Sell high volume AM-produced products for a profit. (Stretch goal.)

Volume

- Make one part – Make one part and be done with it.

- Make five parts – Make a small number of parts and learn support material is a challenge.

- Make fifty parts – Make more than a handful of parts. Filament runs out, machines clog and jam.

- Make parts with a complete manufacturing system – This topic deserves a post all its own.

Complexity

- Make a single piece – Make one part.

- Make a multi-part assembly – Make multiple parts and fasten them together.

- Make a building block assembly – Make blocks that join to form an assembly larger than the build area.

- Consolidate – Redesign an assembly to consolidate multiple parts into fewer.

- Simplify – Redesign the consolidated assembly to eliminate features and simplify it.

Material

- Plastic – Low temperature plastic, multicolor plastics, high performance plastics.

- Metal – Low melting temperature with low conductivity, higher melting temps, higher conductivity

- Ceramics – common materials with standard binders, crazy materials with crazy binders.

- Hybrid – multiple types of plastics in a single part, multiple metals in one part, custom metal alloy.

- Incompatible materials – Think oil and water.

Scale

- 50 mm – Not too large and not too small. Fits the build area of medium-sized machine.

- 500 mm – Larger than the build area of medium-sized machine.

- 5 m – Requires a large machine or joining multiple parts in a building block way.

- 0.5 mm – Tiny parts, tiny machines, superior motion control and material control.

Organizational Breadth

- Individuals – Early adopters operate in isolation.

- Teams – Teams of early adopters gang together and spread the word.

- Functions – Functional groups band together to advance their trade.

- Supply Chain – Suppliers and customers work together to solve joint problems.

- Business Units – Whole business units spread AM throughout the body of their work.

- Company – Whole company adopts AM and deploys it broadly.

Strategic Importance

- Novelty – Early adopters think it’s cool and learn what AM can do.

- Point Solution – AM solves an important problem.

- Speed – AM speeds up the work.

- Profitability – AM improves profitability.

- Initiative – AM becomes an initiative and benefits are broadly multiplied.

- Competitive Advantage – AM generates growth and delivers on Vital Business Objectives (VBOs).

Image credit – Cheryl

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski