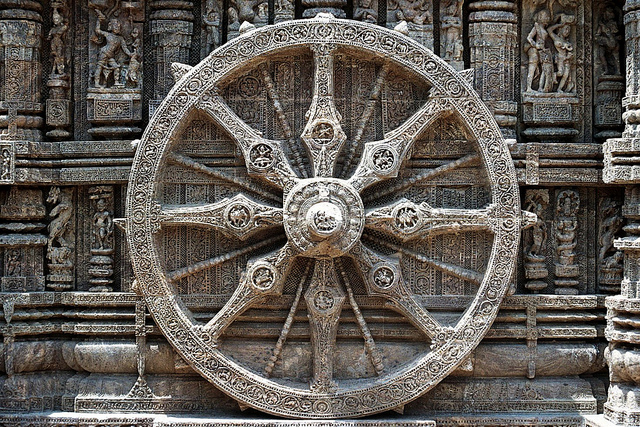

Being Right in the Right Way

When something doesn’t feel right, respect your intuition. Even when you don’t know why it doesn’t feel right, respect your gut. When something doesn’t make sense, don’t judge yourself negatively. Rather, make the commitment to dig deeply until you hit the fundamentals. When a proposed approach violates something inside, don’t be afraid to say what you think is right. Or, be afraid and say it anyway. But right doesn’t mean your predictions will come true. Right means you thought about it, you understand things differently and you have a coherent rationale for thinking as you do. And right also means you don’t understand, but you want to. And right means something does not sit well with you and you don’t know why. And it means the right view is important to you.

When something doesn’t feel right, respect your intuition. Even when you don’t know why it doesn’t feel right, respect your gut. When something doesn’t make sense, don’t judge yourself negatively. Rather, make the commitment to dig deeply until you hit the fundamentals. When a proposed approach violates something inside, don’t be afraid to say what you think is right. Or, be afraid and say it anyway. But right doesn’t mean your predictions will come true. Right means you thought about it, you understand things differently and you have a coherent rationale for thinking as you do. And right also means you don’t understand, but you want to. And right means something does not sit well with you and you don’t know why. And it means the right view is important to you.

Right doesn’t mean correct. And right doesn’t mean something else is wrong. When you have right view, it doesn’t mean you see things exactly right. It means you’re going about things in a way that’s right for the situation. It means your approach feels right to the people involved. It means you’re going about things with the right intention.

Now, like with any new idea, you’re obligated to formalize what you think is right and explain it to your peers. But, to be clear, you’re not looking for permission, you’re writing it down to help you understand what you think. When you try to present your thoughts, you’ll learn what you know and what you don’t. You’ll learn which words work and which don’t. You’ll learn right speech.

And you’ll find the potholes. And that’s why you present to your peers. They’ll be critical of the idea and respectful of you. They’ll tell you the truth because they know it’s better to iron out the details early and often. As a group, you’ll support each other. As a group, you’ll take the right action.

When ideas are introduced that are different, the organization will feel stress. Everyone wants to do a good job, yet there’s no agreement on the right way. Even though there’s stress, no one wants to create harm and everyone wants to behave ethically. It’s important to demonstrate compassion to yourself and others. The stress is natural, but it’s also natural to go about your livelihood in the right way.

But when the stakes are high and there’s no consensus on how to move forward, it’s not easy to hold onto the right mental state. The stress can cause us to delude ourselves into thinking things aren’t going well. But, letting the disagreement go unaddressed is unskillful, as it will only fester. It’s far more skillful to respectfully debate and discuss the disagreement. In that way, everyone makes the right effort to work things out.

Over time, the pattern of behavior can transition to a natural openness where ideas are shared freely. This becomes easier when we drop the mental habit of categorizing things into buckets we like and buckets we don’t. And it helps to maintain awareness of how things really are so we can strip away our subjective options. In this case, mindfulness is the right way to go.

None of this is easy. Our minds are constantly distracted by competing demands, growing to-do lists and organizational complexities of the work. Without dedicated practice, our minds can get lost in a flurry of thoughts of our own creation. To make it work, we’ve got to maintain a heightened alertness to our mental state and that takes the right concentration.

There’s nothing new here, but this well-worn path has merit.

Image credit – saamiblog

How to Choose the Best Idea

We have too many ideas, but too few great ones. We don’t need more ideas, we need a way to choose the best one or two ideas and run them to ground.

We have too many ideas, but too few great ones. We don’t need more ideas, we need a way to choose the best one or two ideas and run them to ground.

Before creating more ideas, make a list of the ones you already have. Put them in two boxes. In Box 1, list the ideas without a video of a functional prototype in action. In Box 2, list the ideas that have a video showing a functional prototype demonstrating the idea in action. For those ideas with a functional prototype and no video, put them in Box 1.

Next, throw away Box 1. If it’s not important enough to make a crude physical prototype and create a simple video, the idea isn’t worth a damn. If someone isn’t willing to carve out the time to make a physical prototype, there’s no emotional energy behind the idea and it should be left to die. And when people complain that it’s unfair to throw away all those good ideas in Box 1, tell them it’s unfair to spend valuable resources talking about ideas that aren’t worthy. And suggest, if they want to have a discussion about an idea, they should build a physical prototype and send you the video. Box 2, or bust.

Next, get the band together and watch the short videos in Box 2, and, as a group, put them in two boxes. In Box 3, put the videos without customers actively using the functional prototype. In Box 4, put the videos with customers actively using the functional prototype.

Next, throw way Box 3. If it’s not important enough to make a trip to an important customer and create a short video, the idea isn’t worth a damn. If you’re not willing to put yourself out there and take the idea to an important customer, the idea is all fizzle and no sizzle. Meaningful ideas take immense personal energy to run through the gauntlet, and without a video of a customer using the functional prototype, there’s not enough energy behind it. And when everyone argues that Box 3 ideas are worth pursuing, tell them to pursue a video showing a most important customer demonstrating the functional prototype.

Next, get the band back together to watch the Box 4 videos. Again, put the videos in two boxes. In Box 5 put the videos where the customer didn’t say what they liked and how they’d use it. In Box 6, put the videos where the customer enthusiastically said what they liked and how they’ll use it.

Next, throw away Box 5. If the customer doesn’t think enough about the prototype to tell you how they’ll use it, it’s because they don’t think much of the idea. And when the group says the customer is wrong or the customer doesn’t understand what the prototype is all about, suggest they create a video where a customer enthusiastically explains how they’d use it.

Next, get the band back in the room and watch the Box 6 videos. Put them in two boxes. In Box 7, put the videos that won’t radically grow the top line. In Box 8, put the videos that will radically grow the top line. Throw away Box 7.

For the videos in Box 8, rank them by the amount of top line growth they will create. Put all the videos back into Box 8, except the video that will create the most top line growth. Do NOT throw away Box 8.

The video in your hand IS your company’s best idea. Immediately charter a project to commercialize the idea. Staff it fully. Add resources until adding resources doesn’t no longer pulls in the launch. Only after the project is fully staffed do you put your hand back into Box 8 to select the next best idea.

Continually evaluate Boxes 1 through 8. Continually throw out the boxes without the right videos. Continually choose the best idea from Box 8. And continually staff the projects fully, or don’t start them.

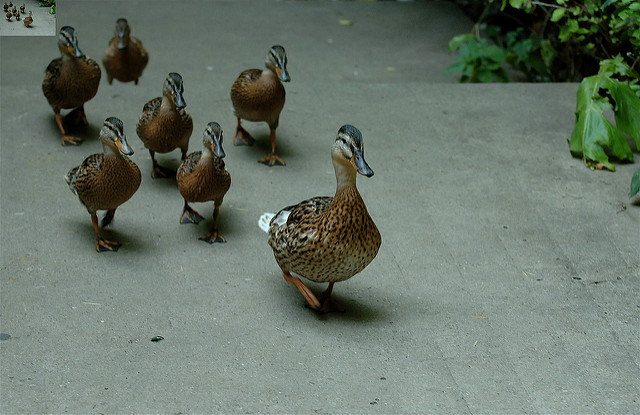

Image credit – joiseyshowaa

Everyday Leadership

What if your primary role every day was to put other people in a position to succeed? What would you start doing? What would you stop doing? Could you be happy if they got the credit and you didn’t? Could you feel good about their success or would you feel angry because they were acknowledged for their success? What would happen if you ran the experiment?

What if your primary role every day was to put other people in a position to succeed? What would you start doing? What would you stop doing? Could you be happy if they got the credit and you didn’t? Could you feel good about their success or would you feel angry because they were acknowledged for their success? What would happen if you ran the experiment?

What if each day you had to give ten compliments? Could you notice ten things worthy of compliment? Could you pay enough attention? Would it be difficult to give the compliments? Would it be easy? Would it scare you? Would you feel silly or happy? Who would be the first person you’d compliment? Who is the last person you’d compliment? How would they feel? What could it hurt to try it for a week?

What if each day you had to ask five people if you can help them? Could you do it even for one day? Could you ask in a way the preserves their self-worth? Could you ask in a sincere way? How do you think they would feel if you asked them? How would you feel if they said yes? How about if they said no? Would the experiment be valuable? Would it be costly? What’s in the way of trying it for a day? How do you feel about what’s in the way?

What if you made a mistake and you had to apologize to five people? Could you do it? Would you do it? Could you say “I’m sorry. I won’t do it again. How can I make it up to you?” and nothing else? Could you look them in the eye and apologize sincerely? If your apology was sincere, how would they feel? And how would you feel? Next time you make a mistake, why not try to apologize like you mean it? What could it hurt? Why not try?

What if every day you had to thank five people? Could you find five things to be thankful for? Would you make the effort to deliver the thanks face-to-face? Could you do it for two days? Could you do it for a week? How would you feel if you actually did it for a week? How would the people around you feel? How do you feel about trying it?

What if every day you tried to be a leader?

Image credit – Pedro Ribeiro Simões

For top line growth, think no-to-yes.

Bottom line growth is good, but top line growth is better. But if you want to grow the bottom line, ignore labor costs and reduce material costs. Labor cost is only 5-10% of product cost. Stop chasing it, and, instead, teach your design community to simplify the product so it uses fewer parts and design out the highest cost elements.

Bottom line growth is good, but top line growth is better. But if you want to grow the bottom line, ignore labor costs and reduce material costs. Labor cost is only 5-10% of product cost. Stop chasing it, and, instead, teach your design community to simplify the product so it uses fewer parts and design out the highest cost elements.

Where the factory creates bottom line growth, top line growth is generated in the market/customer domain. The best way I know to grow the top line is to broaden the applicability of your products and services. But, before you can broaden applicability, you’ve got to define applicability as it is. Define the limits of what your product can do – how much it can lift, how fast it can run a calculation and where it can be used. And for your service, define who can use it, where it can be used and what elements without customer involvement. And with the limits defined, you know where top line growth won’t come from.

Radical top line growth comes only when your products and services can be used in new applications. Sure, you can train your sales force to sell more of what you already have, but that runs out of gas soon enough. But, real top line growth comes when your services serve new customers in new ways. By definition, if you’re not trying to make your product work in new ways, you’re not going to achieve meaningful top line growth. And by definition, if you’re not creating new functionality for your services, you might as well be focusing on bottom line growth.

If your product couldn’t do it and now it can, you’re doing it right. If your service couldn’t be used by people that speak Chinese and now it can, you’re on your way. If your product couldn’t be used in applications without electricity and now it can, you’re on to something. If your service couldn’t run on a smartphone and now it can, well, you get the idea.

For the acid test, think no-to-yes.

If your product can’t work in application A, you can’t sell it to people who do that work. If your service can’t be used by visually impaired people, you’re not delivering value to them and they won’t buy it. Turning can’t into can is a big deal. But you’ve got to define can’t before you can turn it into can. If you want top line growth, take the time to define the limits of applicability.

No-to-yes is powerful because it creates clarity. It’s easy to know when a project will create no-to-yes functionality and when it won’t. And that makes it easy to stop projects that don’t deliver no-to-yes value and start projects that do.

No-to-yes is the key element of a compete-with-no-one approach to business.

image credit – liebeslakritze

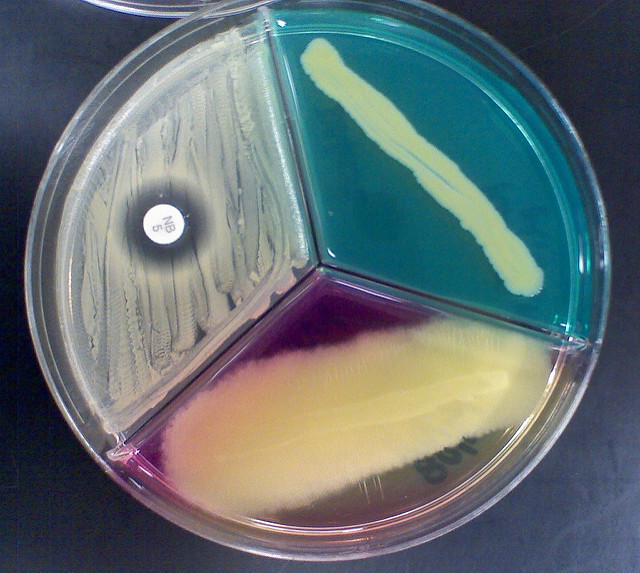

How to Avoid a Cliff

Much like living organisms continually evolve to secure their place in the future, technological systems can be thought to display similar evolutionary behavior. Viruses mutate so some of them can defeat the countermeasures of their host and live to fight another day. Technological systems, as an expression of a company’s desire to survive, evolve to defeat the competition and live to pay another dividend.

Much like living organisms continually evolve to secure their place in the future, technological systems can be thought to display similar evolutionary behavior. Viruses mutate so some of them can defeat the countermeasures of their host and live to fight another day. Technological systems, as an expression of a company’s desire to survive, evolve to defeat the competition and live to pay another dividend.

There are natural limits to evolutionary success in any single direction. When one trait is improved it pushes on the natural limits imposed by the environment. For example, a bacterium let loose in a friendly Petri dish will replicate until it eats all the food in the dish. Or, on a longer timescale, if the mass of a bird increases over generations when its food source is plentiful, the bird will get larger but will also get less agile. The predators who couldn’t catch the fast, little bird of old can easily catch and eat the sluggish heavyweight. In that way, there’s an edge condition created by the environmental Petri dishes and predators. And it’s the same with technological systems.

Companies and their technological systems evolve within their competitive environment by scanning the fitness landscape and deciding where to try to improve. The idea is to see preferential lines of improvement and create new technologies to take advantage of them. Like their smaller biological counterparts, companies are minimum energy creatures and want to maximize reward (profit) with minimum effort (expense) and will continue to leverage successful lines of evolution until it senses diminishing returns.

The diminishing returns are a warning sign that the company is approaching an edge condition (a Petri dish of a finite size). In landscape lingo, there’s a cliff on the horizon. In technology lingo, the rate of improvement of the technology is slowing. In either language, the edge is near and it’s time to evolve in a new direction because this current one is out of gas.

Like the bird whose mass increases over the generations when food is readily available, companies also get fat and slow when they successfully evolve in a single direction for too long. And like the bird, they get eaten by a more agile competitor/predator. And just as the replication rate of the bacterium accelerates as the food in the Petri dish approaches zero, a company that doesn’t react to a slowing rate of technological improvement is sure to outlive its business model.

Biology and technology are similar in that they try new things (create variants of themselves) in order to live another day. But there’s a big difference – where biology is blind (it doesn’t know what will work and what won’t), technology is sighted (people that create use their understanding to choose the variants they think will work best). And another difference is that biological evolution can build only on viable variants where technology can use mental models as scaffolds to skip non-viable embodiments to cross a chasm.

There’s no need to fall off the cliff. As a leading indicator, monitor the rate of improvement of your technology. If its rate of improvement is still accelerating, it’s time to develop the next line of evolution. If its rate is declining, you waited too long. It’s time to double down on two new lines of evolution because you’re behind the curve. And remember, like with the population of bacteria in the Petri dish, sales will keep growing right up until the business model runs out of food or a competitor eats you.

Image credit — Amanda

Creating the Causes and Conditions for New Behavior to Grow

When you see emergent behavior that could grow into a powerful new theme, it’s important to acknowledge the behavior quickly and most publicly. If you see it in person, praise the behavior in front of everyone. Explain why you like it, explain why it’s important, explain what it could become. And as soon as you can find a computer, send an email to their bosses and copy the right-doers. Tell their bosses why you like it, tell them why it’s important, tell them what it could become.

When you see emergent behavior that could grow into a powerful new theme, it’s important to acknowledge the behavior quickly and most publicly. If you see it in person, praise the behavior in front of everyone. Explain why you like it, explain why it’s important, explain what it could become. And as soon as you can find a computer, send an email to their bosses and copy the right-doers. Tell their bosses why you like it, tell them why it’s important, tell them what it could become.

Emergent behavior is like the first shoots of a beautiful orchid that may come to be. To the untrained eye, these little green beauties can look like scraggly weeds pushing out of the dirt. To the tired, overworked leader these new behaviors can like divergence, goofing around and even misbehavior. Without studying the leaves, the fledgling orchid can be confused for crabgrass.

Without initiative there is no new behavior and without new behavior there can be no orchids. When good people solve a problem in a creative way and it goes unacknowledged, the stem of the emergent behavior is clipped. But when the creativity is watered and fertilized the seedling has a chance to grow into something more. The leaders’ time and attention provide the nutrients, the leaders’ praise provides the hydration and their proactive advocacy for more of the wonderful behavior provides the sunlight to fuel the photosynthesis.

When the company demands bushels of grain, it’s a challenge to keep an eye out for the early signs of what could be orchids in the making. But that’s what a leader must do. More often than not, this emergent behavior, this magical behavior, goes unacknowledged if not unnoticed. As leaders, this behavior is unskillful. As leaders, we’ve got to slow down and pay more attention.

When you see the magic in emergent behavior, when you see the revolution it could grow into, and when you look someone in the eye and say – “I’ve got to tell you, what you did was crazy good. What you did could turn things upside down. What you did was inspiring. Thank you.” – you get people’s attention. Not only to do you get the attention of the person you’re talking to, you get the attention of everyone within a ten-foot radius. And thirty minutes later, almost everyone knows about the emergent behavior and the warm sunshine it attracted.

And, magically, without a corporate initiative or top-down deployment, over the next weeks there will be patches of orchids sprouting under desks, behind filing cabinets, on the manufacturing floor, in the engineering labs and in the common areas.

As leaders we must make it easier for new behavior to happen. We must figure a way to slow down and pay attention so we can recognize the seeds of could-be greatness. And to be able to invest the emotional energy needed to protect the seedlings, we must be well-rested. And like we know to provide the right soil, the right fertilizer, the right watering schedule and the right sunlight, we must remember that special behavior we want to grow is a result of causes and conditions we create.

Image credit – Rosemarie Crisasfi

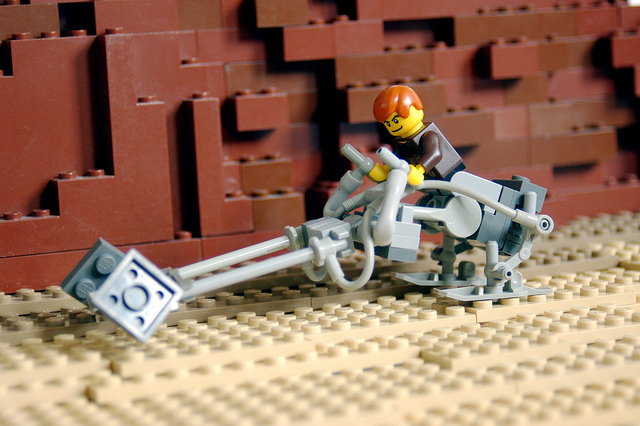

With novelty, less can be more.

When it’s time to create something new, most people try to imagine the future and then put a plan together to make it happen. There’s lots of talk about the idealize future state, cries for a clean slate design or an edict for a greenfield solution. Truth is, that’s a recipe for disaster. Truth is, there is no such thing as a clean slate or green field. And because there are an infinite number of future states, it’s highly improbable your idealized future state is the one the universe will choose to make real.

When it’s time to create something new, most people try to imagine the future and then put a plan together to make it happen. There’s lots of talk about the idealize future state, cries for a clean slate design or an edict for a greenfield solution. Truth is, that’s a recipe for disaster. Truth is, there is no such thing as a clean slate or green field. And because there are an infinite number of future states, it’s highly improbable your idealized future state is the one the universe will choose to make real.

To create something new, don’t look to the future. Instead, sit in the present and understand the system as it is. Define the major elements and what they do. Define connections among the elements. Create a functional diagram using blocks for the major elements, using a noun to name each block, and use arrows to define the interactions between the elements, using a verb to label each arrow. This sounds like a complete waste of time because it’s assumed that everyone knows how the current state system behaves. The system has been the backbone of our success, of course everyone knows the inputs, the outputs, who does what and why they do it.

I have created countless functional models of as-is systems and never has everyone agreed on how it works. More strongly, most of the time the group of experts can’t even create a complete model of the as-is system without doing some digging. And even after three iterations of the model, some think it’s complete, some think it’s incomplete and others think it’s wrong. And, sometimes, the team must run experiments to determine how things work. How can you imagine an idealized future state when you don’t understand the system as it is? The short answer – you can’t.

And once there’s a common understanding of the system as it is, if there’s a call for a clean sheet design, run away. A call for a clean sheet design is sure fire sign that company leadership doesn’t know what they’re doing. When creating something new it’s best to inject the minimum level of novelty and reuse the rest (of the system as it is). If you can get away with 1% novelty and 99% reuse, do it. Novelty, by definition, hasn’t been done before. And things that have never been done before don’t happen quickly, if they happen at all. There’s no extra credit for maximizing novelty. Think of novelty like ghost pepper sauce – a little goes a long way. If you want to know how to handle novelty, imagine a clean sheet design and do the opposite.

Greenfield designs should be avoided like the plague. The existing system has coevolved with its end users so that the system satisfies the right needs, the users know how to use the system and they know what to expect from it. In a hand-in-glove way, the as-is system is comfortable for end users because it fits them. And that’s a big deal. Any deviation from baseline design (novelty) will create discomfort and stress for end users, even if that novelty is responsible for the enhancement you’re trying to deliver. Novelty violates customer expectations and violating customer expectations is a dangerous game. Again, when you think novelty, think ghost peppers. If you want to know how to handle novelty, imagine a green field and do the opposite.

This approach is not incrementalism. Where you need novelty, inject it. And where you don’t need it, reuse. Design the system to maximize new value but do it with minimum novelty. Or, better still, offer less with far less. Think 90% of the value with 10% of the cost.

Image credit – Laurie Rantala

Thoughts on Selling

Like most things, selling is about people.

Like most things, selling is about people.

The hard sell has nothing to do with selling.

Just when you think you’re having the least influence, you’re having the most.

When – ready, sell, listen – has run its course, try – ready, listen, sell.

Regardless of how politely it’s asked, “How many do you want?” isn’t selling.

If sales people are compensated by sales dollars, why do you think they’ll sell strategically?

The time horizon for selling defines the selling.

When people think you’re selling, they’re not thinking about buying.

Selling is more about ears than mouths.

Selling on price is a race to the bottom.

Wanting sales people to develop relationships is a great idea; why not make it worth their while?

Solving customer problems is selling.

Making it easy to buy makes it easy to sell.

You can’t sell much without trust.

Sell like you expect your first sale will happen a year from now.

Selling is a result.

I’m not sure the best way to sell; but listening can’t hurt.

Over-promising isn’t selling, unless you only want to sell once.

Helping customers grow is selling.

Delaying gratification is exceptionally difficult, but it’s wonderful way to sell.

Ground yourself in the customers’ work and the selling will take care of itself.

People buy from people and people sell to people.

Image credit – Kevin Dooley

A Healthy Dose of Heresy

Anything worth its salt will meet with resistance. More strongly, if you get no resistance, don’t bother.

Anything worth its salt will meet with resistance. More strongly, if you get no resistance, don’t bother.

There’s huge momentum around doing what worked last time. Same as last time but better; build on success; leverage last year’s investment; we know how to do it. Why are these arguments so appealing? Two words: comfort and perceived risk. Why these arguments shouldn’t be so appealing: complacency and opportunity cost.

We think statically and selectively. We look in the rear view mirror, write down what happened and say “let’s do that again.” Hey, why not? We made the initial investment and did the leg work. We created the script. Let’s get some mileage out of it. And we selectively remember the positive elements and actively forget the uncertainty of the moment. We had no idea it was going to work, and we forget that part. It worked better than we imagined and we remember the “working better” part. And we forget we imagined it would go differently. And we forget that was a long time ago and we don’t take the time to realize things are different now. The rules are dynamic, yet our thinking is static.

We compete with the past tense. We did this and they did that, and, therefore, that’s what will happen again. So wrong. We’ve got smarter; they’ve got smarter; battery capacity has tripled; power electronics are twice as efficient; efficiency of solar panels has doubled; CRISPR can edit our genes. The rules are different but the sheet music hasn’t changed. The established players sing the same songs and the upstarts cut them off at the knees.

If you were successful last time and everyone thinks your proposed project is a good idea, ball it up and throw it in the trash. It reeks of stale thinking. If your project plan is dismissed by the experts because it contradicts the tired recipe of success, congratulations! You may be onto something! Stomp on the accelerator and don’t look back.

If your proposal meets with consensus, hang your head and try again. You missed the mark. If they scream “heretic” and want to burn you at the stake, double down. If the CEO isn’t adamantly against it, you’re not trying hard enough. If she throws you out of the room half way through your presentation, you may have a winner!

Yesterday’s recipes for success are today’s worn paths of mediocracy.

If you’re confident it will work, you shouldn’t be. If you’re filled with electric excitement it might actually work and scared to death it might end in a wild fireball of burn metal toxic fumes, what are you waiting for?!

Heretics were burned at the stake because the establishment knew they were right. Goddard was right and the New York Times wasn’t. Decades later they apologized – rockets work is space. And though the Qualifiers and Pope Paul V were unanimous in their dismissal of Galileo and Copernicus, the heretics had it right – the sun is at the center of everything.

Don’t seek out dissent, but if all you get is consensus, be wary. Don’t be adversarial, but if all you get is open arms, question your thesis. Don’t be confrontational, but if all you get is acceptance, something’s wrong.

If there’s no resistance, work on something else.

Image Credit WPI (Robert Goddard’s Lab)

What’s your problem?

If you don’t have a problem, you’ve got a big problem.

If you don’t have a problem, you’ve got a big problem.

It’s important to know where a problem happens, but also when it happens.

Solutions are 90% defining and the other half is solving.

To solve a problem, you’ve got to understand things as they are.

Before you start solving a new problem, solve the one you have now.

It’s good to solve your problems, but it’s better to solve you customers’ problems.

Opportunities are problems in sheep’s clothing.

There’s nothing worse than solving the wrong problem – all the cost with none of the solution.

When you’re stumped by a problem, make it worse then do the opposite.

With problem definition, error on the side of clarity.

All problems are business problems, unless you care about society’s problems.

Odds are, your problem has been solved by someone else. Your real problem is to find them.

Define your problem as narrowly as possible, but no narrower.

Problems are not a sign of weakness.

Before adding something to solve the problem, try removing something.

If your problem involves more than two things, you have more than one problem.

The problem you think you have is never the problem you actually have.

Problems can be solved before, during or after they happen and the solutions are different.

Start with the biggest problem, otherwise you’re only getting ready to solve the biggest problem.

If you can’t draw a closeup sketch of the problem, you don’t understand it well enough.

If you have an itchy backside and you scratch you head, you still have an itch. And it’s the same with problems.

If innovation is all about problem solving and problem solving is all about problem definition, well, there you have it.

Image credit – peasap

The Leader’s Journey

If you know what to do, do it. Don’t ask, just do.

If you know what to do, do it. Don’t ask, just do.

If you’re pretty sure what to do, do it. Don’t ask, just do.

If you think you may know what to do, do it. Don’t ask, just do.

If you don’t know what to do, try something small. Then, do more of what works and less of what doesn’t.

If your team doesn’t know what to do unless they ask you, tell them to do what they think is right. And tell them to stop asking you what to do.

If your team won’t act without your consent, tell them to do what they think is right. Then, next time they seek your consent, be unavailable.

If the team knows what to do and they go around you because they know you don’t, praise them for going around you. Then, set up a session where they educate you on what you should know.

If the team knows what to do and they know you don’t, but they don’t go around you because they are too afraid, apologize to them for creating a fear-based culture and ask them to do what they think is right. Then, look inside to figure out how to let go of your insecurities and control issues.

If your team needs your support, support them.

If your team need you to get out of the way, go home early.

If your team needs you to break trail, break it.

If they need to see how it should go, show them.

If they need the rules broken, break them.

If they need the rules followed, follow them.

If they need to use their judgement, create the causes and conditions for them to use their judgement.

If they try something new and it doesn’t go as anticipated, praise them for trying something new.

If they try the same thing a second time and they get the same results and those results are still unanticipated, set up a meeting to figure out why they thought the same experiment would lead to different results.

Try to create the team that excels when you go on vacation.

Better yet, try to create the team that performs extremely well when you’re involved in the work and performs even better when you’re on vacation. Then, because you know you’ve prepared them for the future, happily move on to your next personal development opportunity.

Image credit — Puriri deVry

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski