Advice To Young Design Engineers

If your solution isn’t sold to a customer, you didn’t do your job. Find a friend in Marketing.

If your solution can’t be made by Manufacturing, you didn’t do your job. Find a friend in Manufacturing.

Reuse all you can, then be bold about trying one or two new things.

Broaden your horizons.

Before solving a problem, make sure you’re solving the right one.

Don’t add complexity. Instead, make it easy for your customers.

Learn the difference between renewable and non-renewable resources and learn how to design with the renewable ones.

Learn how to do a Life Cycle Assessment.

Learn to see functional coupling and design it out.

Be afraid but embrace uncertainty.

Learn how to communicate your ideas in simple ways. Jargon is a sign of weakness.

Before you can make sure you’re solving the right problem, you’ve got to know what problem you’re trying to solve.

Learn quickly by defining the tightest learning objective.

Don’t seek credit, seek solutions. Thrive, don’t strive.

Be afraid, and run toward the toughest problems.

Help people. That’s your job.

Image credit – Marco Verch

An Environmental Call-To-Arms for Industry

What is your obligation to improve the health of our planet?

What is your obligation to improve the health of our planet?

For the CEO – Look around. Look at Europe. Look at China’s plans. Look at the startups. I know you want to achieve your growth objectives, but if you don’t take seriously the race toward cleaner products and services, you’ll go out of business. You can see this as a problem or an opportunity. Bury your head or put on your track shoes and run! It’s your choice.

Look at the oceans. Look at the landfills. Look at the rise in global temperatures. Just look. This isn’t about ROI, this is about survival. Growth objectives aside, no one will buy things when they are struggling to survive in an uncertain future. Your same old dirty products won’t cut it anymore. So, what are you going to do?

For an example of a path forward, look to the companies in the oil business. Their recipe is clear. They’ve got to use their large but ever-diminishing profits to buy themselves into technologies and industries that will ultimately eat their core business. Though the timing is uncertain, it’s certain that improvements in cleaner technologies will demand they make the change.

Whatever you do, don’t wait. You don’t have much time. Cleaner technologies are getting better every day. It’s time to start.

For Marketing – Look at the upstarts. Look at the powerful companies in adjacent markets who will soon be your direct competitors. Look at your stodgy, unprofitable competitors who are now sufficiently desperate to try anything. Their next marketing push will be built on the bedrock of an improved planet. They’ll be almost as good as you in the traditional areas of productivity and quality and they’ll blow your doors off with their meaner and greener products. Customers will choose green over brown. And they’ll look for real improvements that make the planet smile. The time for green-washing is past. That trick is out of gas.

You need to help customers with new jobs to be done. They care about their environment. They care about their carbon footprint. They care about clean water. And they care about recycling and reuse. It’s real. They care. Now it’s up to you to help them make progress in these areas. It will be a tough road to convince your company that things need to change, but that’s why you’re in Marketing.

You’re already behind. It’s time to start. And it’s up to you to lead the charge.

For Manufacturing – Look at your Value Stream Maps (VSMs). Assign a carbon footprint to each link in the chain. And do the same with water consumption. Assess each process step for carbon and water and rank them worst to best. For the worst, run carbon kaizens and improve the carbon footprint. And run water kaizens for the thirstiest processes.

And look again at your VSMs, and look more broadly. Look back into the supply chain, rank for carbon and water and improve the ones that need the treatment. And teach your suppliers how to do it. And look forward into your distribution channels and improve or eliminate the worst actors. And then propose to Marketing that you teach your customers how to use VSMs to clean up their act. And challenge Engineering to change the design to eliminate the remaining bad actors.

You’ve made good progress with your value streams. Now it’s time to help others make the progress that must be made. As subject matter experts, it’s your time to shine. And, please, start now.

For Engineering – Look at your products. Look at how they’re used. Look at how they’re delivered. Look at how they’re made. Look at how they’re recycled. Sure, your products provide good functionality, but throughout their life cycle they also create carbon dioxide and consume water. And you’re the only ones that can design out the environmental impact.

Learn how to do a Life Cycle Assessment (LCA). Learn which elements of the product create the largest problems. For all the parts that make up the product, sort them worst to best to prioritize the design work. It’s time for radical part count reduction. Try to design out half the parts. It’s possible. And the payoff is staggering. What’s the carbon footprint of a part that was designed out of the product?

Or, to make a more radical improvement, consider an Innovation Burst Event (IBE) to make a fundamental change in the way your products/services impact the environment. With this approach, your innovation work, by definition, will make the planet smile.

It’s time to be open-minded. Ask Manufacturing for the worst processes (including supply chain and distribution) and try to design them out. Design out the part, or change the material, or change the design to enable a friendlier process. Manufacturing can only improve a bad process, but you can design them out altogether. There’s power in that, but with power comes responsibility.

And it’s time for you to take responsibility.

For Everyone in Industry – Regardless of your company, your country or your political affiliation, we can all agree that all our lives get better as the health of our planet improves. And everyone can agree that cleaner air is better. And everyone can agree it’s the same for our water – cleaner is better. And that’s a whole lot of agreement.

As industry leaders, I challenge you to build on that common ground. As industry leaders, I challenge you to improve our planet one product at a time and one process at a time. And as industry leaders, I challenge you to help each other. There’s no competitive disadvantage when you help a company outside your industry. And there’s no shame in learning from companies outside your industry. And it’s good for the planet and profits. There’s nothing in the away. It’s time to start.

As an industry leader, if you want to make a difference in the health of our planet, send me an email at mike@shipulski.com and we will help each other.

Image credit – halfrain

Organizational Learning

The people within companies have development plans so they can learn new things and become more effective. There are two types of development plans – one that builds on strengths and another that shore up shortcomings. And for both types, the most important step is to acknowledge it’s important to improve. Before a plan can be created to improve on a strength, there must be recognition that something good can come from the improvement. And before there can be a plan to improve on a shortcoming, there must be recognition that there’s something missing and it needs to be improved.

The people within companies have development plans so they can learn new things and become more effective. There are two types of development plans – one that builds on strengths and another that shore up shortcomings. And for both types, the most important step is to acknowledge it’s important to improve. Before a plan can be created to improve on a strength, there must be recognition that something good can come from the improvement. And before there can be a plan to improve on a shortcoming, there must be recognition that there’s something missing and it needs to be improved.

And thanks to Human Resources, the whole process is ritualized. The sequence is defined, the timing is defined and the tools are defined. Everyone knows when it will happen, how it will happen and, most importantly, that it will happen. In that way, everyone knows it’s important to learn new skills for the betterment of all.

Organizational learning is altogether different and more difficult. With personal learning, it’s clear who must do the learning (the person). But with organizational learning, it’s unclear who must learn because the organization, as a whole, must learn. But we can’t really see the need for organizational learning because we get trapped in trying to fix the symptoms. Team A has a problem, so let’s fix Team A. Or, Team B has a problem, so let’s fix Team B. But those are symptoms. Real organizational learning comes when we recognize problematic themes shared by all the teams. Real organization learning comes when we realize these problems don’t result from doing things wrong, rather, they are a natural byproduct of how the company goes about its work.

The difficulty with organizational learning is not fixing the thematic problems. The difficulty is recognizing the thematic problems. When all the processes are followed and all the best practices are used, yet the same problematic symptoms arise, the problem is inherent in the foundational processes and practices. Yet, these are the processes and practices responsible for past success. It’s difficult for company leaders recognize and declare that the things that made the company successful are now the things that are holding the company back. But that’s the organizational learning that must happen.

What worked last time will work next time, as long as the competitive landscape remains constant. But when the landscape changes, what worked last time doesn’t work anymore. And this, I think, is how recipes responsible for past success can, over time, begin to show cracks and create these systematic problems that are so difficult to see.

The best way I know to recognize the need for organizational learning is to recognize changes in the competitive landscape. Once these changes are recognized, thought experiments can be run to evaluate potential impacts on how the company does business. Now that the landscape changed like this, it could stress our business model like that. Now that our competitors provide new services like this, it could create a gap in our capabilities like that.

Organizational learning occurs when the right leaders feel the problems. Fight the urge to fix the problems. Instead, create the causes and conditions for the right leaders to recognize they have a real problem on their hands.

Image credit – Jim Bauer

Why not choose the right words?

We all want to make progress. We all want to to do the right thing. And we all have the best intentions. But often we don’t pay enough attention to the words we use.

We all want to make progress. We all want to to do the right thing. And we all have the best intentions. But often we don’t pay enough attention to the words we use.

There are pure words that convey a message in a kind soothing way and there are snarl words that convey a message in a sharp, biting way. It’s relatively easy, if you’re paying attention, to recognize the snarl and purr. But it’s much more difficult to take skillful action when you hear them used unskillfully.

A purr word is skillful when it conveys honest appreciation, and it’s unskillful when it manipulates under the banner of false praise. But how do you tell the difference? That’s where the listening comes in. And that’s where effective probing can help.

If you sense unskillful use, ask a question of the user to get at the intent behind the language. Why do you think the idea is so good? What about the concept do you find so interesting? Why do you like it so much? Then, use your judgment to decide if the use was unskillful or not. If unskillful, assign less value to the purr language and the one purring it.

But it’s different with snark words. I don’t know of a situation where the use of snarl words is skillful. Blatant use of snarl words is easy to see and interpret. And it looks like plain, old-fashioned anger. And the response is straightforward. Call the snarler on their snarl and let them know it’s not okay. That usually puts an end to future snarling.

The most dangerous use of snarl words is passive-aggressive snarling. Here, the snarler wants all the manipulative benefit without being recognized as a manipulator. The pros snarl lightly to start to see if they get away with it. And if they do, they snarl harder and more often. And they won’t stop until they’re called on their behavior. And when they are called on their behavior, they’ll deny the snarling altogether.

Passive-aggressive snarling can block new thinking, prevent consensus and stall hard-won momentum. It’s nothing short of divisive. And it’s difficult to see and requires courage to confront and eviscerate.

If you see something, say something. And it’s the same with passive-aggressive snarling. If you think it is happening, ask questions to get at the underlying intent of the words. If it turns out that it’s simply a poor choice of words, suggest better ones and move on. But if the intent is manipulation, it must be stopped in its tracks. It must be called by name, its negative implications must be be linked to the behavior and new behavioral norms must be set.

Words are the tools we use to make progress. The wrong words block progress and the right ones accelerate it.

Why not choose the right words?

Four Questions to Choose Innovation Projects

It’s a challenge to prioritize and choose innovation projects. There are open questions on the technology, the product/service, the customer, the price and sales volume. Other than that, things are pretty well defined.

It’s a challenge to prioritize and choose innovation projects. There are open questions on the technology, the product/service, the customer, the price and sales volume. Other than that, things are pretty well defined.

But with all that, you’ve still go to choose. Here are some questions that may help in your selection process

Is it big enough? The project will be long, expensive and difficult. And if the potential increase in sales is not big enough, the project is not worth starting. Think (Price – Cost) x Volume. Define a minimum viable increase in sales and bound it in time. For example, the minimum incremental sales is twenty five million dollars after five years in the market. If the project does not have the potential to meet those criteria, don’t do the project. The difficult question – How to estimate the incremental sales five years after launch? The difficult answer – Use your best judgement to estimate sales based on market size and review your assumptions and predictions with seasoned people you trust.

Why you? High growth markets/applications are attractive to everyone, including the big players and the well-funded start-ups. How does your company have an advantage over these tough competitors? What about your company sets you apart? Why will customers buy from you? If you don’t have good answers, don’t start the project. Instead, hold the work hostage and take the time to come up with good answers. If you come up with good answers, try to answer the next questions. If you don’t, choose another project.

How is it different? If the new technology can’t distinguish itself over existing alternatives, you don’t have a project worth starting. So, how is your new offering (the one you’re thinking about creating) better than the ones that can be purchased today? What’s the new value to the customer? Or, in the lingo of the day, what is the Distinctive Value Proposition (DVP)? If there’s no DVP, there’s no project. If you’re not sure of the DVP, figure that out before investing in the project. If you have a DVP but aren’t sure it’s good enough, figure out how to test the DVP before bringing the DVP to life.

Is it possible? Usually, this is where everyone starts. But I’ve listed it last, and it seems backward. Would you rather spend a year making it work only to learn no one wants it, or would you rather spend a month to learn the market wants it then a year making it work? If you make it work and no one wants it, you’ve wasted a year. If, before you make it work, you learn no one wants it, you’ve spent a month learning the right thing and you haven’t spent a year working on the wrong thing. It feels unnatural to define the market need before making it work, but though it feels unnatural, it can block resources from working on the wrong projects.

There is no foolproof way to choose the best innovation projects, but these four questions go a long way. Create a one-page template with four sections to ask the questions and capture the answers. The sections without answers define the next work. Define the learning objectives and the learning activities and do the learning. Fill in the missing answers and you’re ready to compare one project to another.

Sort the projects large-to-small by Is it big enough? Then, rank the top three by Why you? and How is it different? Then, for the highest ranked project, do the work to answer Is it possible?

If it’s possible, commercialize. If it’s not, re-sort the remaining projects by Is it big enough? Why you? and How is it different? and learn if It is possible.

Image credit – Ben Francis

Four Pillars of Innovation – People, Learning, Judgment and Trust

Innovation is a hot topic. Everyone wants to do it. And everyone wants a simple process that works step-wise – first this, then that, then success.

Innovation is a hot topic. Everyone wants to do it. And everyone wants a simple process that works step-wise – first this, then that, then success.

But Innovation isn’t like that. I think it’s more effective to think of innovation as a result. Innovation as something that emerges from a group of people who are trying to make a difference. In that way, Innovation is a people process. And like with all processes that depend on people, the Innovation process is fluid, dynamic, complex, and context-specific.

Innovation isn’t sequential, it’s not linear and cannot be scripted.. There is no best way to do it, no best tool, no best training, and no best outcome. There is no way to predict where the process will take you. The only predictable thing is you’re better off doing it than not.

The key to Innovation is good judgment. And the key to good judgment is bad judgment. You’ve got to get things wrong before you know how to get them right. In the end, innovation comes down to maximizing the learning rate. And the teams with the highest learning rates are the teams that try the most things and use good judgement to decide what to try.

I used to take offense to the idea that trying the most things is the most effective way. But now, I believe it is. That is not to say it’s best to try everything. It’s best to try the most things that are coherent with the situation as it is, the market conditions as they are, the competitive landscape as we know it, and the the facts as we know them.

And there are ways to try things that are more effective than others. Think small, focused experiments driven by a formal learning objective and supported by repeatable measurement systems and formalized decision criteria. The best teams define end implement the tightest, smallest experiment to learn what needs to be learned. With no excess resources and no wasted time, the team wins runs a tight experiment, measures the feedback, and takes immediate action based on the experimental results.

In short, the team that runs the most effective experiments learns the most, and the team that learns the most wins.

It all comes down to choosing what to learn. Or, another way to look at it is choosing the right problems to solve. If you solve new problems, you’ll learn new things. And if you have the sightedness to choose the right problems, you learn the right new things.

Sightedness is a difficult thing to define and a more difficult thing to hone and improve. If you were charged with creating a new business in a new commercial space and the survival of the company depended on the success of the project, who would you want to choose the things to try? That person has sightedness.

Innovation is about people, learning, judgement and trust.

And innovation is more about why than how and more about who than what.

Image credit – Martin Nikolaj Christensen

The only thing predictable about innovation is its unpredictability.

A culture that demands predictable results cannot innovate. No one will have the courage to do work with the requisite level of uncertainty and all the projects will build on what worked last time. The only predictable result – the recipe will be wildly successful right up until the wheels fall off.

A culture that demands predictable results cannot innovate. No one will have the courage to do work with the requisite level of uncertainty and all the projects will build on what worked last time. The only predictable result – the recipe will be wildly successful right up until the wheels fall off.

You can’t do work in a new area and deliver predictable results on a predictable timetable. And if your boss asks you to do so, you’re working for the wrong person.

When it comes to innovation, “ecosystem,” as a word, is unskillful. It doesn’t bound or constrain, nor does it show the way. How about a map of the system as it is? How about defined boundaries? How about the system’s history? How about the interactions among the system elements? How about a fitness landscape and the system’s disposition? How about the system’s reason for being? The next evolution of the system is unpredictable, even if you call it an ecosystem.

If you can’t tolerate unpredictability, you can’t tolerate innovation.

Innovation isn’t about reducing risk. Innovation is about maximizing learning rate. And when all things go as predicted, the learning rate is zero. That’s right. Learning decreases when everything goes as planned. Are you sure you want predictable results?

Predictable growth in stock price can only come from smartly trying the right portfolio of unpredictable projects. That’s a wild notion.

Innovation runs on the thoughts, feelings, emotions and judgement of people and, therefore, cannot be predictable. And if you try to make it predictable, the best people, the people that know the drill, will leave.

The real question that connects innovation and predictability: How to set the causes and conditions for people to try things because the results are unpredictable?

With innovation, if you’re asking for predictability, you’re doing it wrong.

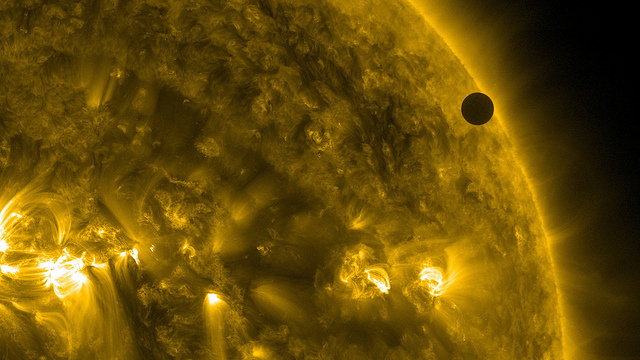

Image credit: NASA Goddard

Healthy Dissatisfaction

If you’re dissatisfied, there’s a reason.

If you’re dissatisfied, there’s a reason.

If you’re dissatisfied, there’s hope for us all.

If you’re not dissatisfied, there’s no forcing function for change.

If you’re not dissatisfied, the status quo will carry the day.

If you’re not dissatisfied, innovation work is not for you.

If you’re dissatisfied, you know it could be better next time.

If you’re dissatisfied, your insecure leader will step on your head.

If you’re dissatisfied, there’s a reason and that reason is real.

If you’re dissatisfied, follow your dissatisfaction.

If you’re dissatisfied, I want to work with you.

If you’re dissatisfied, it’s because you see things as they are.

If you’re dissatisfied, your confident leader will ask how things should go next time.

If you’re dissatisfied, it’s because you want to make a difference.

If you’re dissatisfied, look inside.

If you’re dissatisfied, there’s a reason, the reason is real and it’s time to do something about it.

If you’re dissatisfied, you’re thinking for yourself.

If you’re so dissatisfied you openly show anger, thank you for trusting me enough to show your true self.

If you’re dissatisfied, it’s because you know things should be better than they are.

If you’re dissatisfied, do something about it.

If you’re dissatisfied, thank you for thinking deeply.

If you’re dissatisfied, it’s because you’re not asleep at the wheel.

If you’re dissatisfied, it’s because your self-worth allows it.

Thank you for caring enough to be dissatisfied.

Image credit – Vinod Chandar

How To Innovate Within a Successful Company

If you’re trying to innovate within a successful company, I have one word for you: Don’t.

If you’re trying to innovate within a successful company, I have one word for you: Don’t.

You can’t compete with the successful business teams that pay the bills because paying the bills is too important. No one in their right mind should get in the way of paying them. And if you do put yourself in the way of the freight train that pays the bills you’ll get run over. If you want to live to fight another day, don’t do it.

If an established business has been growing three percent year-on-year, expect them to grow three percent next year. Sure, you can lather them in investment, but expect three and a half percent. And if they promise six percent, don’t believe them. In fairness, they truly expect they can grow six percent, but only because they’re drinking their own Cool-Aid.

Rule 1: If they’re drinking their own Cool-Aid, don’t believe them.

Without a cataclysmic problem that threatens the very existence of a successful company, it’s almost impossible to innovate within its four walls. If there’s no impending cataclysm, you have two choices: leave the four walls or don’t innovate.

It’s great to work at successful company because it has a recipe that worked. And it sucks to work at a successful company because everyone thinks that tired old recipe will work for the next ten years. Whether it will work for the next ten or it won’t, it’s still a miserable place to work if you want to try something new. Yes, I said miserable.

What’s the one thing a successful company needs? A group of smart people who are actively dissatisfied with the status quo. What’s the one thing a successful company does not tolerate? A group of smart people who are actively dissatisfied with the status quo.

Some experts recommend leveraging (borrowing) resources from the established businesses and using them to innovate. If the established business catches wind that their borrowed resources will be used to displace the status quo, the resources will mysteriously disappear before the innovation project can start. Don’t try to borrow resources from established businesses and don’t believe the experts.

Instead of competing with established businesses for resources, resources for innovation should be allocated separately. Decide how much to spend on innovation and allocate the resources accordingly. And if the established businesses cry foul, let them.

Instead of borrowing resources from established businesses to innovate, increase funding to the innovation units and let them buy resources from outside companies. Let them pay companies to verify the Distinctive Value Proposition (DVP); let them pay outside companies to design the new product; let them pay outside companies to manufacture the new product; and let them pay outside companies to sell it. Sure, it will cost money, but with that money you will have resources that put their all into the design, manufacture and sale of the innovative new offering. All-in-all, it’s well worth the money.

Don’t fall into the trap of sharing resources, especially if the sharing is between established businesses and the innovative teams that are charged with displacing them. And don’t fall into the efficiency trap. Established businesses need efficiency, but innovative teams need effectiveness.

It’s not impossible to innovate within a successful company, but it is difficult. To make it easier, error on the side of doing innovation outside the four walls of success. It may be more expensive, but it will be far more effective. And it will be faster. Resources borrowed from other teams work the way they worked last time. And if they are borrowed from a successful team, they will work like a successful team. They will work with loss aversion. Instead of working to bring something to life they will work to prevent loss of what worked last time. And when doing work that’s new, that’s the wrong way to work.

The best way I know to do innovation within a successful company is to do it outside the successful company.

Image credit – David Doe

Defy success and choose innovation.

Innovation is difficult because it requires novelty. And novelty is difficult because it’s different than last time. And different than last time is difficult because you’ve got to put yourself out there. And putting yourself out there is difficult because no one wants to be judged negatively.

Innovation is difficult because it requires novelty. And novelty is difficult because it’s different than last time. And different than last time is difficult because you’ve got to put yourself out there. And putting yourself out there is difficult because no one wants to be judged negatively.

Success, no matter how small, reinforces what was done last time. There’s safety in doing it again. The return may be small, but the wheels won’t fall off. You may run yourself into the ground over time, but you won’t fail catastrophically. You may not reach your growth targets, but you won’t get fired for slowly destroying the brand. In short, you won’t fail this year, but you will create the causes and conditions for a race to the bottom.

Diminishing returns are real. As a system improves it becomes more difficult to improve. A ten percent improvement is more difficult every year and at some point, improvement becomes impossible. In that way, success doesn’t breed success, it breeds more effort for less return. And as that improvement per unit effort decreases, it becomes ever more important (and ever more difficult) to do something different (to innovate).

Paradoxically, success makes it more difficult to innovate.

Success brings profits that could fund innovation. But, instead, success brings the expectation of predictable growth. Last year we were successful and grew 10%. We know the recipe, so this year let’s grow 12%. We can do what we did last year, but do it more efficiently. A sound bit of logic, except it assumes the rules haven’t changed and that competitors haven’t improved. But rules and competitors always change, and, at some point the the same old recipe for success runs out of gas.

It’s time to do something new (to innovate) when the same old effort brings reduced results. That change in output per unit effort means the recipe is tiring and it’s time for a new one. But with a new approach comes unpredictability, and for those who demand predictability, a new approach is scary. Sure, the yearly trend of reduced return on investment should scare them more, but it doesn’t. The devil you know is less scary than the one you don’t. But, it shouldn’t be.

Calculate your revenue dollars per sales associate and plot it over time. If the metric is flat over the last three years, it was time to innovate three years ago. If it’s decreasing over the last three years, it was time to innovate six years ago.

If you wait to innovate until revenue per sales person is flat, you waited too long.

No one likes to be judged negatively, more than that, no one likes their company to collapse and lose their job. So, choose to do something new (to innovate) and choose the possibility of being judged. That’s much better than choosing to go out of business.

Image credit – Michel Rathwell

Important Questions for Innovation

Here are some important questions for innovation.

Here are some important questions for innovation.

What’s the Distinctive Value Proposition? The new offering must help the customer make progress. How does the customer benefit? How is their life made easier? How does this compare to the existing offerings? Summarize the difference on one page. If the innovation doesn’t help the customer make progress, it’s not an innovation.

Is it too big or too small? If the project could deliver sales growth that would dwarf the existing sales numbers for the company, the endeavor is likely too big. The company mindset and philosophy would have to be destroyed. Are you sure you’re up to the challenge? If the project could deliver only a small increase in sales, it’s likely not worth the time and expense. Think return on investment. There’s no right answer, but it’s important to ask the question and set the limits for too big and too small. If it could grow to 10% of today’s sales numbers, that’s probably about right.

Why us? There’s got to be a reason why you’re the right company to do this new work. List the company’s strengths that make the work possible. If you have several strengths that give you an advantage, that’s great. And if one of your weaknesses gives you an advantage, that works too. Step on the accelerator. If none of your strengths give you an advantage, choose another project.

How do we increase our learning rate? First thing, define Learning Objectives (LOs). And once defined, create a plan to achieve them quickly. Here’s a hint. Define what it takes to satisfy the LOs. Here’s another hind. Don’t build a physical prototype. Instead, create a website that describes the potential offering and its value proposition and ask people if they want to buy it. Collect the data and refine the offering based on your learning. Or, create a one-page sales tool and show it to ten potential customers. Define your learning and use the learning to decide what to do next.

Then what? If the first phase of the work is successful, there must be a then what. There must be an approved plan (funding, resources) for the second phase before the first phase starts. And the same thing goes for the follow-on phases. The easiest way to improve innovation effectiveness is avoid starting phase one of projects when their phase two is unfunded. The fastest innovation project is the wrong one that never starts.

How do we start? Define how much money you want to spend. Formalize your business objectives. Choose projects that could meet your business objectives. Free up your best people. Learn as quickly as you can.

Image credit — Alexander Henning Drachmann

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski