People, Money and Time

If you want the next job, figure out why.

There’s nothing wrong with wanting the job you have.

When you don’t care about the next job it’s because you fit the one you have.

A larger salary is good, but time with family is better.

Less time with family is a downward spiral into sadness.

When you decide you have enough, you don’t need things to be different.

A sense of belonging lasts longer than a big bonus.

A cohesive team is an oasis.

Who you work with makes all the difference.

More stress leads to less sleep and that leads to more stress.

If you’re not sleeping well, something’s wrong.

How much sleep do you get? How do you feel about that?

Leaders lead people.

Helping others grow IS leadership.

Every business is in the people business.

To create trust, treat people like they matter. It’s that simple.

When you do something for someone even though it comes at your own expense, they remember.

You know you’ve earned trust when your authority trumps the org chart.

Image credit — Jimmy Baikovicius

Speed Through Better Decision Making

If you want to go faster there are three things to focus on: decisions, decisions, and decisions.

If you want to go faster there are three things to focus on: decisions, decisions, and decisions.

First things first – define the decision criteria before the work starts. That’s right – before. This is unnatural and difficult because decision criteria are typically poorly defined, if not undefined, even when the work is almost complete. Don’t believe me? Try to find the agreed-upon decision criteria for an active project. If you can find them, they’ll be ambiguous and incomplete. If you can’t find them, well, there you go.

Decision criteria aren’t just categories -like sales revenue, speed, weight – they all must have a go-no-go threshold. Sales must be greater than X, speed must be greater than Y and weight must be less than Z. A decision criterion is a category with a threshold value.

Second, before the work starts, define the actions you’ll take if the threshold values are achieved and if they are not. If sales are greater than X, speed is greater than Y and weight is less than Z, we’ll invest A dollars a year for B years to scale the business. If one of X, Y or Z are less than their threshold value, we’ll scrap the project and distribute the team throughout the organization.

Lastly, before the work starts, define the decision-maker and how their decision will be documented and communicated. In practice, there is usually just one decision-maker. So, strive to write down just one person’s name as the decision-maker. But that person will be reluctant to sign up as the decision-maker because they don’t want to be mapped the decision if things flop. Instead, the real decision-maker will put together a committee to make the decision.

To tighten things down for the committee, define how the decision will be made. Will it be a simple majority vote, a supermajority, unanimous decision or the purposefully ambiguous consensus vote. My bet is on consensus, which allows the individual committee members to distance themselves from the decision if it goes badly. And, it allows the real decision-maker to influence the consensus and effectively make the decision without making it.

Formalizing the decision process creates speed. The decision categories help the team avoid the wrong work and the threshold values eliminate the time-wasting is-it-good-enough arguments. When the follow-on actions are predefined, there’s no waiting there’s just action. And defining upfront the decision-maker and the mechanism eliminates the time-sucking ambiguity that delays decisions.

What Good Ideas Feel Like

If you have a reasonably good idea, someone will steal it, make it their own and take credit. No worries, this is what happens with reasonably good ideas.

If you have a really good idea, you’ll have to explain it several times before anyone understands it. Then, once they understand, you’ll have to help them figure out how to realize value from the idea. And after several failed attempts at implementation, you’ll have to help them adjust their approach so they can implement successfully. Then, after the success, someone will make it their own and take credit. No worries, this is what happens with really good ideas.

When you have an idea so good that it threatens the Status Quo, you’ll get ridiculed. You’ll have to present the idea once every three months for two years. The negativity will decrease slowly, and at the end of two years the threatening idea will get downgraded to a really good idea. Then it will follow the wandering path to success described above. Don’t feel special. This is how it goes with ideas good enough to threaten.

And then there’s the rarified category that few know about. This is the idea that’s so orthogonal it scares even you. This idea takes a year or two of festering before you can scratch the outer shell of it. Then it takes another year before you can describe it to yourself. And then it takes another year before you can bring yourself to speak of it. And then it takes another six months before you share it outside your trust network. And where the very best ideas get ridiculed, with this type of idea people don’t talk about the idea at all, they just think you’ve gone off the deep end and become unhinged. This class of idea is so heretical it makes people uncomfortable just to be near you. Needless to say, this class of idea makes for a wild ride.

Good ideas make people uncomfortable. That’s just the way it is. But don’t let this get in the way. More than that, I urge you to see the push-back and discomfort as measures of the idea’s goodness.

If there’s no discomfort, ridicule or fear, the idea simply isn’t good enough.

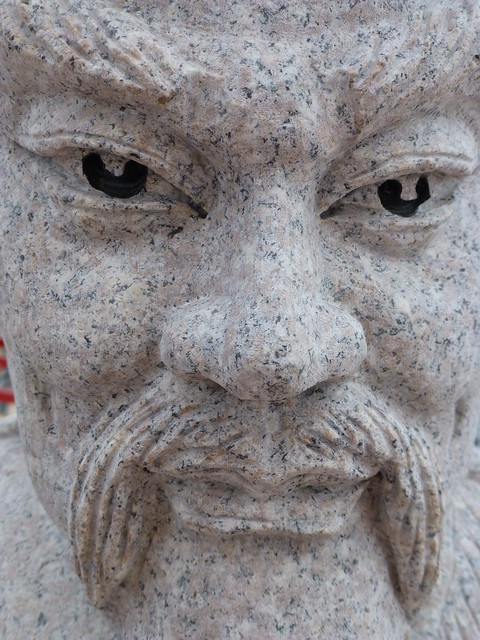

Image credit – Mindaugas Danys

The Difficulty of Commercializing New Concepts

If you have the data that says the market for the new concept is big enough, you waited too long.

If you have the data that says the market for the new concept is big enough, you waited too long.

If you require the data that verifies the market is big enough before pursuing new concepts, you’ll never pursue them.

If you’re afraid to trust the judgement of your best technologists, you’ll never build the traction needed to launch new concepts.

If you will sell the new concept to the same old customers, don’t bother. You already sold them all the important new concepts. The returns have already diminished.

If you must sell the new concept to new customers, it could create a whole new business for you.

If you ask your successful business units to create and commercialize new concepts, they’ll launch what they did last time and declare it a new concept.

If you leave it to your successful business units to decide if it’s right to commercialize a new concept created by someone else, they won’t.

If a new concept is so significant that it will dwarf the most successful business unit, the most successful business unit will scuttle it.

If the new concept is so significant it warrants a whole new business unit, you won’t make the investment because the sales of the yet-to-be-launched concept are yet to be realized.

If you can’t justify the investment to commercialize a new concept because there are no sales of the yet-to-be-launched concept, you don’t understand that sales come only after you launch. But, you’re not alone.

If a new concept makes perfect sense, you would have commercialized it years ago.

If the new concept isn’t ridiculed by the Status Quo, do something else.

If the new concept hasn’t failed three times, it’s not a worthwhile concept.

If you think the new concept will be used as you intend, think again.

If you’re sure a new concept will be a flop, you shouldn’t be. Same goes for the ones you’re sure will be successful.

If you’re afraid to trust your judgement, you aren’t the right person to commercialize new concepts.

And if you’re not willing to put your reputation on the line, let someone else commercialize the new concept.

Image credit – Melissa O’Donohue

As a leader, be truthful and forthcoming.

Have you ever felt like you weren’t getting the truth from your leader? You know – when they say something and you know that’s not what they really think. Or, when they share their truth but you can sense that they’re sharing only part of the truth and withholding the real nugget of the truth? We really have no control over the level of forthcoming of our leaders, but we do have control over how we respond to their incomplete disclosure.

There are times when leaders cannot, by law, disclose things. But, even then, they can make things clear without disclosing what legally cannot be disclosed. For example, they can say: “That’s a good question and it gets to the heart of the situation. But, by law, I cannot answer that question.” They did not answer the question, but they did. They let you know that you understand the situation; they let you know that there is an answer; and the let you know why they cannot share it with you. As the recipient of that non-answer answer, I respect that leader.

There are also times when a leader withholds information or gives a strategically partial response for inappropriate reasons. When a leader withholds information to manipulate or control, that’s inappropriate. It’s also bad leadership. When a leader withholds information from their smartest team members, they lose trust. And when leaders lose trust, the best people are crestfallen and withhold their best work. The thinking goes like this. If my leader doesn’t trust me enough to share the complete set of information with me it’s because they don’t think I’m worthy of their trust and they don’t think highly of me. And if they don’t think I’m worthy of their trust, they don’t understand who I am and what I stand for. And if they don’t understand me and know what I stand for, they’re not worthy of my best work.

As a leader, you must share all you can. And when you can’t, you must tell your team there are things you can’t share and tell them the reasons why. Your team can handle the fact that there are some things you cannot share. But what your team cannot hand is when you withhold information so you can gain the upper hand on them. And your team can tell when you’re withholding with your best interest in mind. Remember, you hired them because they were smart, and their smartness doesn’t go away just because you want to control them.

If your direct reports always tell you they can get it done even when they don’t have the capacity and capability, that’s not the behavior you want. If your direct reports tell you they can’t get it done when they can’t get it done, that’s the behavior you want. But, as a leader, which behavior do you reward? Do you thank the truthful leader for being truthful about the reality of insufficient resources and do you chastise the other leader for telling you what you want to hear? Or, do you tell the truthful leader they’re not a team player because team players get it done and praise the unjustified can-do attitude of the “yes man” leader? As a leader, I suggest you think deeply about this. As a direct report of a leader, I can tell you I’ve been punished for responding in way that was in line with the reality of the resources available to do the work. And I can also tell you that I lost all respect for that leader.

As a leader, you have three types of direct reports. Type I are folks are happy where they are and will do as little as possible to keep it that way. Type II are people that are striving for the next promotion and will tell you whatever you want to hear in order to get the next job. Type III are the non-striving people who will tell you what you need to hear despite the implications to their career. Type I people are good to have on your team. They know what they can do and will tell you when the work is beyond their capability. Type II people are dangerous because they think only of themselves. They will hang you out to dry if they think it will advance their career. And Type III people are priceless.

Type III people care enough to protect you. When you ask them for something that can’t be done, they care enough about you to tell you the truth. It’s not that they don’t want to get it done, they know they cannot. And they’re willing to tell you to your face. Type II people don’t care about you as a leader; they only care about themselves. They say yes when they know the answer is no. And they do it in a way that absolves them of responsibility when the wheels fall off. As a leader, which type do you want on your team? And as a leader, which type do you promote and which do you chastise. And, how do you feel about that?

As a leader, you must be truthful. And when you can’t disclose the full truth, tell people. And when your Type II direct reports give you the answer they know you want to hear, call them on their bullshit. And when your Type III folks give you the answer they know you don’t want to hear, thank them.

Image credit — Anandajoti Bhikkhu

Transcending a Culture of Continuous Improvement

We’ve been too successful with continuous improvement. Year-on-year, we’ve improved productivity and costs. We’ve improved on our existing products, making them slightly better and adding features.

Our recipe for success is the same as last year plus three percent. And because the customers liked the old one, they’ll like the new one just a bit more. And the sales can sell the new one because its sold the same way as the old one. And the people that buy the new one are the same people that bought the old one.

Continuous improvement is a tried-and-true approach that has generated the profits and made us successful. And everyone knows how to do it. Start with the old one and make it a little better. Do what you did last time (and what you did the time before). The trouble is that continuous improvement runs out of gas at some point. Each year it gets harder to squeeze out a little more and each year the return on investment diminishes. And at some point, the same old improvements don’t come. And if they do, customers don’t care because the product was already better than good enough.

But a bigger problem is that the company forgets to do innovative work. Though there’s recognition it’s time to do something different, the organization doesn’t have the muscles to pull it off. At every turn, the organization will revert to what it did last time.

It’s no small feat to inject new work into a company that has been successful with continuous improvement. A company gets hooked on the predictable results of continuous which grows into an unnatural aversion to all things different.

To start turning the innovation flywheel, many things must change. To start, a team is created and separated from the continuously improving core. Metrics are changed, leadership is changed and the projects are changed. In short, the people, processes, and tools must be built to deal with the inherent uncertainty that comes with new work.

Where continuous improvement is about the predictability of improving what is, innovation is about the uncertainty of creating what is yet to be. And the best way I know to battle uncertainty is to become a learning organization. And the best way to start that journey is to create formal learning objectives.

Define what you want to learn but make sure you’re not trying to learn the same old things. Learn how to create new value for customers; learn how to deliver that value to new customers; learn how to deliver that new value in new ways (new business models.)

If you’re learning the same old things in the same old way, you’re not doing innovation.

Innovation Truths

If it’s not different, it can’t be innovation.

If it’s not different, it can’t be innovation.

With innovation, ideas are the easy part. The hard part is creating the engine that delivers novel value to customers.

The first goal of an innovation project is to earn the right to do the second hardest thing. Do the hardest thing first.

Innovation is 50% customer, 50% technology and 75% business model.

If you know how it will turn out, it’s not innovation.

Don’t invest in a functional prototype until customers have placed orders for the sell-able product.

If you don’t know how the customer will benefit from your innovation, you don’t know anything.

If your innovation work doesn’t threaten the status quo, you’re doing it wrong.

Innovation moves at the speed of people.

If you know when you’ll be finished, you’re not doing innovation.

With innovation, the product isn’t your offering. Your offering is the business model.

If you’re focused on best practices, you’re not doing innovation. Innovation is about doing things for the first time.

If you think you know what the customer wants, you don’t.

Doing innovation within a successful company is seven times hard than doing it in a startup.

If you’re certain, it’s not innovation.

With innovation, ideas and prototypes are cheap, but building the commercialization engine is ultra-expensive.

If no one will buy it, do something else.

Technical roadblocks can be solved, but customer/market roadblocks can be insurmountable.

The first thing to do is learn if people will buy your innovation.

With innovation, customers know what they don’t want only after you show them your offering.

With innovation, if you’re not scared to death you’re not trying hard enough.

The biggest deterrent to innovation is success.

Image credit — Sherman Geronimo-Tan

Seeing Things as They Can’t Be

When there’s a big problem, the first step is to define what’s causing it. To do that, based on an understanding of the physics, a sequence of events is proposed and then tested to see if it replicates the problem. In that way, the team must understand the system as it is before the problem can be solved.

When there’s a big problem, the first step is to define what’s causing it. To do that, based on an understanding of the physics, a sequence of events is proposed and then tested to see if it replicates the problem. In that way, the team must understand the system as it is before the problem can be solved.

Seeing things as they are. The same logic applies when it’s time to improve an existing product or service. The first thing to do is to see the system as it is. But seeing things as they are is difficult. We have a tendency to see things as we want them or to see them in ways that make us look good (or smart). Or, we see them in a way that justifies the improvements we already know we want to make.

To battle our biases and see things as they are, we use tools such as block diagrams to define the system as it is. The most important element of the block diagram is clarity. The first revision will be incorrect, but it must be clear and explicit. It must describe things in a way that creates a singular understanding of the system. The best block diagrams can be interpreted only one way. More strongly, if there’s ambiguity or lack of clarity, the thing has not yet risen to the level of a block diagram.

The block diagram evolves as the team converges on a single understanding of things as they are. And with a diagram of things as they are, a solution is readily defined and validated. If when tested the proposed solution makes the problem go away, it’s inferred that the team sees things as they are and the solution takes advantage of that understanding to make the problem go away.

Seeing things as they may be. Even whey the solution fixes the problem, the team really doesn’t know if they see things as they are. Really, all they know is they see things as they may be. Sure, the solution makes the problem go away, but it’s impossible to really know if the solution captures the physics of failure. When the system is large and has a lot of moving parts, the team cannot see things as they are, rather, they can only see the system as it may be. This is especially true if the system involves people, as people behave differently based on how they feel and what happened to them yesterday.

There’s inherent uncertainty when working with larger systems and systems that involve people. It’s not insurmountable, but you’ve got to acknowledge that your understanding of the system is less than perfect. If your company is used to solving small problems within small systems, there will be little tolerance for the inherent uncertainty and associated unpredictability (in time) of a solution. To help your company make the transition, replace the language of “seeing things as they are” with “seeing things as they may be.” The same diagnostic process applies, but since the understanding of the system is incomplete or wrong, the proposed solutions cannot not be pre-judged as “this will work” and “that won’t work.” You’ve got to be open to all potential solutions that don’t contradict the system as it may be. And you’ve got to be tolerant of the inherent unpredictability of the effort as a whole.

Seeing things as they could be. To create something that doesn’t yet exist, something does things like never before, something altogether new, you’ve got to stand on top of your understanding of the system and jump off. Whether you see things as they are or as they may be, the new system will be different. It’s not about diagnosing the existing system; it’s about imagining the system as it could be. And there’s a paradox here. The better you understand the existing system, the more difficulty you’ll have imagining the new one. And, the more success the company has had with the system as it is, the more resistance you’ll feel when you try to make the system something it could be.

Seeing things as they could be takes courage – courage to obsolete your best work and courage to divest from success. The first one must be overcome first. Your body creates stress around the notion of making yourself look bad. If you can create something altogether better, why didn’t you do it last time? There’s a hit to the ego around making your best work look like it’s not all that good. But once you get over all that, you’ve earned the right to go to battle with your organization who is afraid to move away from the recipe responsible for all the profits generated over the last decade.

But don’t look at those fears as bad. Rather, look at them as indicators you’re working on something that could make a real difference. Your ego recognizes you’re working on something better and it sends fear into your veins. The organization recognizes you’re working on something that threatens the status quo and it does what it can to make you stop. You’re onto something. Keep going.

Seeing things as they can’t be. This is rarified air. In this domain you must violate first principles. In this domain you’ve got to run experiments that everyone thinks are unreasonable, if not ill-informed. You must do the opposite. If your product is fast, your prototype must be the slowest. If the existing one is the heaviest, you must make the lightest. If your reputation is based on the highest functioning products, the new offering must do far less. If your offering requires trained operators, the new one must prevent operator involvement.

If your most seasoned Principal Engineer thinks it’s a good idea, you’re doing it wrong. You’ve got to propose an idea that makes the most experienced people throw something at you. You’ve got to suggest something so crazy they start foaming at the mouth. Your concepts must rip out their fillings. Where “seeing things as they could be” creates some organizational stress, “seeing things as they can’t be” creates earthquakes. If you’re not prepared to be fired, this is not the domain for you.

All four of these domains are valuable and have merit. And we need them all. If there’s one message it’s be clear which domain you’re working in. And if there’s a second message it’s explain to company leadership which domain you’re working in and set expectations on the level of uncertainty and unpredictability of that domain.

Image credit – David Blackwell.

Don’t change culture. Change behavior.

There’s always lots of talk about culture and how to change it. There is culture dial to turn or culture level to pull. Culture isn’t a thing in itself, it’s a sentiment that’s generated by behavioral themes. Culture is what we use to describe our worn paths of behavior. If you want to change culture, change behavior.

There’s always lots of talk about culture and how to change it. There is culture dial to turn or culture level to pull. Culture isn’t a thing in itself, it’s a sentiment that’s generated by behavioral themes. Culture is what we use to describe our worn paths of behavior. If you want to change culture, change behavior.

At the highest level, you can make the biggest cultural change when you change how you spend your resources. Want to change culture? Say yes to projects that are different than last year’s and say no to the ones that rehash old themes. And to provide guidance on how to choose those new projects create, formalize new ways you want to deliver new value to new customers. When you change the criteria people use to choose projects you change the projects. And when you change the projects people’s behaviors change. And when behavior changes, culture changes.

The other important class of resources is people. When you change who runs the project, they change what work is done. And when they prioritize a different task, they prioritize different behavior of the teams. They ask for new work and get new behavior. And when those project leaders get to choose new people to do the work, they choose in a way that changes how the work is done. New project leaders change the high-level behaviors of the project and the people doing the work change the day-to-day behavior within the projects.

Change how projects are chosen and culture changes. Change who runs the projects and culture changes. Change who does the project work and culture changes.

Image credit – Eric Sonstroem

When it rains, don’t blame the clouds.

When it rains, you get wet. It doesn’t matter if you get mad at the clouds, you still get wet. And if you curse the sky, you still get wet. So, why the anger and cursing? Do you really think the clouds see you’re outside and choose to rain on you? Do you think the sky is out to get you?

When someone aims snarl words at you, you get angry because you take it personally. But, their harsh words are about them, not you. And they’re not aiming at you; you just happen to be near them when the words jump out of their mouth. Like the clouds don’t choose to rain on you; you just happen to be under them when their water comes out.

It’s much easier to accept that the clouds are not out to get you because the clouds are not people. It takes a lot of personal work to let someone’s snarl words pass through you. But if a screen door can do it, so can you.

The screen door lets the breeze pass through. It doesn’t flap or flutter, it just lets the hot air pass. It’s there when it’s time to block the bugs but not there when it’s time to let the breeze pass. The screen door doesn’t take the breeze personally, it lets it pass through.

When someone snarls at you, be a screen door and let those words pass through. Try to remember their words are about them, not you. When the snarl words are swirling, don’t be there emotionally. Don’t own their words; don’t accept their gift. Don’t be there emotionally.

But after the storm of words dissipates, be there for them. Ask them what’s bothering them. Listen. Try to understand. Empathize. I bet you’ll learn what’s really going on with them.

In the heat of the moment, it’s easy to take things personally. But if you visualize them as a cloud, maybe you can weather the storm they are trying to create. Or, it may be easier to imagine yourself as a screen door and let their words pass.

Either way, cloud or screen door, it takes practice. And either way, it can make a big difference in your happiness.

Wanting things to be different

Wanting things to be different is a good start, but it’s not enough. To create conditions for things to move in a new direction, you’ve got to change your behavior. But with systems that involve people, this is not a straightforward process.

To create conditions for the system to change, you must understand the system”s disposition – the lines along which it prefers to change.. And to do that, you’ve got to push on the system and watch its response. With people systems, the response is not knowable before the experiment.

If you expect to be able to predict how the system will respond, working with people systems can be frustrating. I offer some guidance here. With this work, you are not responsible for the system’s response, you are only responsible for how you respond to the system’s response.

If the system responds in a way you like, turn that experiment into a project to amplify the change. If the system responds in a way you dislike, unwind the experiment. Here’s a simple mantra – do more of what works and less of what doesn’t. (Thanks to Dave Snowden for this.)

If you don’t like how things are going, you have only one lever to pull. You can only change.your response to what you see and experience. You can respond by pushing on the system and responding to what you see or you can respond by changing what you think and feel about the system.

But keep in mind that you are part of the system. And maybe the system is running an experiment on you. Either way, your only choice is to choose how to respond.

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski