Archive for the ‘Top Line Growth’ Category

Testing is an important part of designing.

When you design something, you create a solution to a collection of problems. But it goes far beyond creating the solution. You also must create objective evidence that demonstrates that the solution does, in fact, solve the problems. And the reason to generate this evidence is to help the organization believe that the solution solves the problem, which is an additional requirement that comes with designing something. Without this belief, the organization won’t go out to the customer base and convince them that the solution will solve their problems. If the sales team doesn’t believe, the customers won’t believe.

When you design something, you create a solution to a collection of problems. But it goes far beyond creating the solution. You also must create objective evidence that demonstrates that the solution does, in fact, solve the problems. And the reason to generate this evidence is to help the organization believe that the solution solves the problem, which is an additional requirement that comes with designing something. Without this belief, the organization won’t go out to the customer base and convince them that the solution will solve their problems. If the sales team doesn’t believe, the customers won’t believe.

In school, we are taught to create the solution, and that’s it. Here are the drawings, here are the materials to make it, here is the process documentation to build it, and my work here is done. But that’s not enough.

Before designing the solution, you’ve got to design the tests that create objective evidence that the solution actually works, that it provides the right goodness and it solves the right problems. This is an easy thing to say, but for a number of reasons, it’s difficult to do. To start, before you can design the right tests, you’ve got to decide on the right problems and the right goodness. And if there’s disagreement and the wrong tests are defined, the design community will work in the wrong areas to generate the wrong value. Yes, there will be objective evidence, and, yes, the evidence will create a belief within the organization that problems are solved and goodness is achieved. But when the sales team takes it to the customer, the value proposition won’t resonate and it won’t sell.

Some questions to ask about testing. When you create improvements to an existing product, what is the family of tests you use to characterize the incremental goodness? And a tougher question: When you develop a new offering that provides new lines of goodness and solves new problems, how do you define the right tests? And a tougher question: When there’s disagreement about which tests are the most important, how do you converge on the right tests?

Image credit — rjacklin1975

Stop reusing old ideas and start solving new problems.

Creating new ideas is easy. Sit down, quiet your mind, and create a list of five new ideas. There. You’ve done it. Five new ideas. It didn’t take you a long time to create them. But ideas are cheap.

Creating new ideas is easy. Sit down, quiet your mind, and create a list of five new ideas. There. You’ve done it. Five new ideas. It didn’t take you a long time to create them. But ideas are cheap.

Converting ideas into sellable products and selling them is difficult and expensive. A customer wants to buy the new product when the underlying idea that powers the new product solves an important problem for them. In that way, ideas whose solutions don’t solve important problems aren’t good ideas. And in order to convert a good idea into a winning product, dirt, rocks, and sticks (natural resources) must be converted into parts and those parts must be assembled into products. That is expensive and time-consuming and requires a factory, tools, and people that know how to make things. And then the people that know how to sell things must apply their trade. This, too, adds to the difficulty and expense of converting ideas into winning products.

The only thing more expensive than converting new ideas into winning products is reusing your tired, old ideas until your offerings run out of sizzle. While you extend and defend, your competitors convert new ideas into new value propositions that bring shame to your offering and your brand. (To be clear, most extend-and-defend programs are actually defend-and-defend programs.) And while you reuse/leverage your long-in-the-tooth ideas, start-ups create whole new technologies from scratch (new ideas on a grand scale) and pull the rug out from under you. The trouble is that the ultra-high cost of extend-and-defend is invisible in the short term. In fact, when coupled with reuse, it’s highly profitable in the moment. It takes years for the wheels to fall off the extend-and-defend bus, but make no mistake, the wheels fall off.

When you find the urge to create a laundry list of new ideas, don’t. Instead, solve new problems for your customers. And when you feel the immense pressure to extend and defend, don’t. Instead, solve new problems for your customers.

And when all that gets old, repeat as needed.

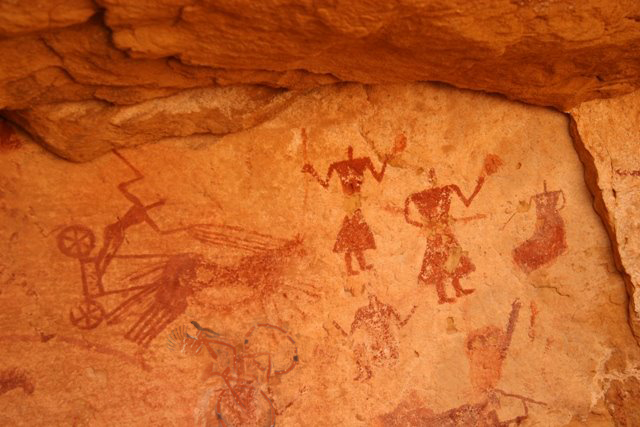

“Cave paintings” by allspice1 is licensed under CC BY-ND 2.0

What do you like to do?

I like to help people turn complex situations into several important learning objectives.

I like to help people turn complex situations into several important learning objectives.

I like to help people turn important learning objectives into tight project plans.

I like to help people distill project plans into a single-page spreadsheet of who does what and when.

I like to help people start with problem definition.

I like to help people stick with problem definition until the problems solve themselves.

I like to help people structure tight project plans based on resource constraints.

I like to help people create objective measures of success to monitor the projects as they go.

I like to help people believe they can do the almost impossible.

I like to help people stand three inches taller after they pull off the unimaginable.

I like to help people stop good projects so they can start amazing ones.

If you want to do more of what you like and less of what you don’t, stop a bad project to start a good one.

So, what do you like to do?

Image credit — merec0

Three Things for the New Year

Next year will be different, but we don’t know how it will be different. All we know is that it will be different.

Next year will be different, but we don’t know how it will be different. All we know is that it will be different.

Some things will be the same and some will be different. The trouble is that we won’t know which is which until we do. We can speculate on how it will be different, but the Universe doesn’t care about our speculation. Sure, it can be helpful to think about how things may go, but as long as we hold on to the may-ness of our speculations. And we don’t know when we’ll know. We’ll know when we know, but no sooner. Even when the Operating Plan declares the hardest of hard dates, the Universe sets the learning schedule on its own terms, and it doesn’t care about our arbitrary timelines.

What to do?

Step 1. Try three new things. Choose things that are interesting and try them. Try to try them in parallel as they may interact and inform each other. Before you start, define what success looks like and what you’ll do if they’re successful and if they’re not. Defining the follow-on actions will help you keep the scope small. For things that work out, you’ll struggle to allocate resources for the next stages, so start small. And if things don’t work out, you’ll want to say that the projects consumed little resources and learned a lot. Keep things small. And if that doesn’t work, keep them smaller.

Step 2. Rinse and repeat.

I wish you a happy and safe New Year. And thanks for reading.

Mike

“three” by Travelways.com is licensed under CC BY 2.0

The Two Sides of the Story

When you tell the truth and someone reacts negatively, their negativity is a surrogate for significance.

When you tell the truth and someone reacts negatively, their negativity is a surrogate for significance.

When you withhold the truth because someone will react negatively, you do everyone a disservice.

When you know what to do, let someone else do it.

When you’re absolutely sure what to do, maybe you’ve been doing it too long.

When you’re in a situation of complete uncertainty, try something. There’s no other way.

When you’re told it’s a bad idea, it’s probably a good one, but for a whole different reason.

When you’re told it’s a good idea, it’s time to come up with a less conventional idea.

When you’re afraid to speak up, your fear is a surrogate for importance.

When you’re afraid to speak up and you don’t, you do your company a disservice.

When you speak up and are met with laughter, congratulations, your idea is novel.

When you get angry, that says nothing about the thing you’re angry about and everything about you.

When someone makes you angry, that someone is always you.

When you’re afraid, be afraid and do it anyway.

When you’re not afraid, try harder.

When you’re understood the first time you bring up a new idea, it’s not new enough.

When you’re misunderstood, you could be onto something. Double down.

When you’re comfortable, stop what you’re doing and do something that makes you uncomfortable.

It’s time to get comfortable with being uncomfortable.

“mirror-image pickup” by jasoneppink is licensed under CC BY 2.0

How To Be Novel

By definition, the approach that made you successful will become less successful over time and, eventually, will run out of gas. This fundamental is not about you or your approach, rather it’s about the nature of competition and evolution. There’s an energy that causes everything to change, grow and improve and your success attracts that energy. The environment changes, the people change, the law changes and companies come into existence that solve problems in better and more efficient ways. Left unchanged, every successful business endeavor (even yours) has a half-life.

By definition, the approach that made you successful will become less successful over time and, eventually, will run out of gas. This fundamental is not about you or your approach, rather it’s about the nature of competition and evolution. There’s an energy that causes everything to change, grow and improve and your success attracts that energy. The environment changes, the people change, the law changes and companies come into existence that solve problems in better and more efficient ways. Left unchanged, every successful business endeavor (even yours) has a half-life.

If you want to extend the life of your business endeavor, you’ve got to be novel.

By definition, if you want to grow, you’ve got to raise your game. You’ve got to do something different. You can’t change everything, because that’s inefficient and takes too long. So, you’ve got to figure out what you can reuse and what you’ve got to reinvent.

If you want to grow, you’ve got to be novel.

Being novel is necessary, but expensive. And risky. And scary. And that’s why you want to add just a pinch of novelty and reuse the rest. And that’s why you want to try new things in the smallest way possible. And that’s why you want to try things in a time-limited way. And that’s why you want to define what success looks like before you test your novelty.

Some questions and answers about being novel:

Is it easy to be novel? No. It’s scary as hell and takes great emotional strength.

Can anyone be novel? Yes. But you need a good reason or you’ll do what you did last time.

How can I tell if I’m being novel? If you’re not scared, you’re not being novel. If you know how it will turn out, you’re not being novel. If everyone agrees with you, you’re not being novel.

How do I know if I’m being novel in the right way? You cannot. Because it’s novel, it hasn’t been done before, and because it hasn’t been done before there’s no way to predict how it will go.

So, you’re saying I can’t predict the outcome of being novel? Yes.

If I can’t predict the outcome of being novel, why should I even try it? Because if you don’t, your business will go away.

Okay. That last one got my attention. So, how do I go about being novel? It depends.

That’s not a satisfying answer. Can you do better than that? Well, we could meet and talk for an hour. We’d start with understanding your situation as it is, how this current situation came to be, and talk through the constraints you see. Then, we’d talk about why you think things must change. I’d then go away for a couple of days and think about things. We’d then get back together and I’d share my perspective on how I see your situation. Because I’m not a subject matter expert in your field, I would not give you answers, but, rather, I’d share my perspective that you could use to inform your choice on how to be novel.

“Giraffe trying to catch a twig with her tongue” by Tambako the Jaguar is licensed under CC BY-ND 2.0

If you want to understand innovation, understand novelty.

If you want to get innovation right, focus on novelty.

If you want to get innovation right, focus on novelty.

Novelty is the difference between how things are today and how they might be tomorrow. And that comparison calibrates tomorrow’s idea within the context of how things are today. And that makes all the difference. When you can define how something is novel, you have an objective measure of things.

How is it different than what you did last time? If you don’t know, either you don’t know what you did last time or you don’t know the grounding principle of your new idea. Usually, it’s a little of the former and a whole lot of the latter. And if you don’t know how it’s different, you can’t learn how potential customers will react to the novelty. In fact, if you don’t know how it’s different, you can’t even decide who are the right potential customers.

A new idea can be novel in unique ways to different customer segments and it can be novel in opposite ways to intermediaries or other partners in the business model. A customer can see the novelty as something that will make them more profitable and an intermediary can see that same novelty as something that will reduce their influence with the customer and lead to their irrelevance. And, they’ll both be right.

Novelty is in the eye of the beholder, so you better look at it from their perspective.

Like with hot sauce, novelty comes in a range of flavors and heat levels. Some novelty adds a gentle smokey flavor to your favorite meal and makes you smile while the ghost pepper variety singes your palate and causes you to lose interest in the very meal you grew up on. With novelty, there is no singular level of Scoville Heat Unit (SHU) that is best. You’ve got to match the heat with the situation. Is it time to improve things a bit with a smokey, yet subtle, chipotle? Or, is it time to submerge things in pure capsaicin and blow the roof off? The good news is the bad news – it’s your choice.

With novelty, you can choose subtle or spicy. Choose wisely.

And like with hot sauce, novelty doesn’t always mix well with everything else on the plate. At the picnic, when you load your plate with chicken wings, pork ribs, and apple pie, it’s best to keep the hot sauce away from the apple pie. Said more strongly, with novelty, it’s best to use separate plates. Separate the teams – one team to do heavy novelty work, the disruptive work, to obsolete the status quo, and a separate team to the lighter novelty work, the continuous improvement work, to enhance the existing offering.

Like with hot sauce, different people have different tolerance levels for novelty. For a given novelty level, one person can be excited while another can be scared. And both are right. There’s no sense in trying to change a person’s tolerance for novelty, they either like it or they don’t. Instead of trying to teach them to how to enjoy the hottest hot sauce, it’s far more effective to choose people for the project whose tolerance for novelty is in line with the level of novelty required by the project.

Some people like habanero hot sauce, and some don’t. And it’s the same with novelty.

Run toward the action!

Companies have control over one thing: how to allocate their resources. Companies allocate resources by deciding which projects to start, accelerate, and stop; whom to allocate to the projects; how to go about the projects; and whom to hire, invest in, and fire. That’s it.

Companies have control over one thing: how to allocate their resources. Companies allocate resources by deciding which projects to start, accelerate, and stop; whom to allocate to the projects; how to go about the projects; and whom to hire, invest in, and fire. That’s it.

Taking a broad view of project selection to include starting, accelerating, and stopping projects, as a leader, what is your role in project selection, or, at a grander scale, initiative selection? When was the last time you initiated a disruptive yet heretical new project from scratch? When was the last time you advocated for incremental funding to accelerate a floundering yet revolutionary project? When was the last time you stopped a tired project that should have been put to rest last year? And because the projects are the only thing that generates revenue for your company, how do you feel about all that?

Without your active advocacy and direct involvement, it’s likely the disruptive project won’t see the light of day. Without you to listen to the complaints of heresy and actively disregard them, the organization will block the much-needed disruption. Without your brazen zeal, it’s likely the insufficiently-funded project won’t revolutionize anything. Without you to put your reputation on the line and decree that it’s time for a revolution, the organization will starve the project and the revolution will wither. Without your critical eye and thought-provoking questions, it’s likely the tired project will limp along for another year and suck up the much-needed resources to fund the disruptions, revolutions, and heresy.

Now, I ask you again. How do you feel about your (in)active (un)involvement with starting projects that should be started, accelerating projects that should be accelerated, and stopping projects that should be stopped?

And with regard to project staffing, when was the last time you stepped in and replaced a project manager who was over their head? Or, when was the last time you set up a recurring meeting with a project manager whose project was in trouble? Or, more significantly, when was the last time you cleared your schedule and ran toward the smoke of an important project on fire? Without your involvement, the over-their-head project manager will drown. Without your investment in a weekly meeting, the troubled project will spiral into the ground. Without your active involvement in the smoldering project, it will flame out.

As a leader, do you have your fingers on the pulse of the most important projects? Do you have the knowledge, skills, and abilities to know which projects need help? And do you have the chops to step in and do what must be done? And how do you feel about all that?

As a leader, do you know enough about the work to provide guidance on a major course change? Do you know enough to advise the project team on a novel approach? Do you have the gumption to push back on the project team when they don’t want to listen to you? As a leader, how do you feel about that?

As a leader, you probably have direct involvement in important hiring and firing decisions. And that’s good. But, as a leader, how much of your time do you spend developing young talent? How many hours per week do you talk to them about the details of their projects and deliverables? How many hours per week do you devote to refactoring troubled projects with the young project managers? And how do you feel about that?

If you want to grow revenue, shape the projects so they generate more revenue. If you want to grow new businesses, advocate for projects that create new businesses. If you need a revolution, start revolutionary projects and protect them. And if you want to accelerate the flywheel, help your best project managers elevate their game.

“Speeding Pinscher” by PincasPhoto is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Taking vacations and holidays are the most productive things you can do.

It’s not a vacation unless you forget about work.

It’s not a vacation unless you forget about work.

It’s not a holiday unless you leave your phone at home.

If you must check-in at work, you’re not on vacation.

If you feel guilty that you did not check-in at work, you’re not on holiday.

If you long for work while you’re on vacation, do something more interesting on vacation.

If you wish you were at work, you get no credit for taking a holiday.

If people know you won’t return their calls, they know you are on vacation.

If people would rather make a decision than call you, they know you’re on holiday.

If you check your voicemail, you’re not on vacation.

If you check your email, you’re not on holiday.

If your company asks you to check-in, they don’t understand vacation.

If people at your company invite you to a meeting, they don’t understand holiday.

Vacation is productive in that you return to work and you are more productive.

Holiday is not wasteful because when you return to work you don’t waste time.

Vacation is profitable because when you return you make fewer mistakes.

Holiday is skillful because when you return your skills are dialed in.

Vacation is useful because when you return you are useful.

Holiday is fun because when you return you bring fun to your work.

If you skip your vacation, you cannot give your best to your company and to yourself.

If neglect your holiday, you neglect your responsibility to do your best work.

Don’t skip your vacation and don’t neglect your holiday. Both are bad for business and for you.

“CatchingButterflies on Vacation” by OakleyOriginals is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Certainty or novelty – it’s your choice.

When you follow the best practice, by definition your work is not new. New work is never done the same way twice. That’s why it’s called new.

When you follow the best practice, by definition your work is not new. New work is never done the same way twice. That’s why it’s called new.

Best practices are for old work. Usually, it’s work that was successful last time. But just as you can never step into the same stream twice, when you repeat a successful recipe it’s not the same recipe. Almost everything is different from last time. The economy is different, the competitors are different, the customers are in a different phase of their lives, the political climate is different, interest rates are different, laws are different, tariffs are different, the technology is different, and the people doing the work are different. Just because work was successful last time doesn’t mean that the old work done in a new context will be successful next time. The most important property of old work is the certainty that it will run out of gas.

When someone asks you to follow the best practice, they prioritize certainty over novelty. And because the context is different, that certainty is misplaced.

We have a funny relationship with certainty. At every turn, we try to increase certainty by doing what we did last time. But the only thing certain with that strategy is that it will run out of gas. Yet, frantically waving the flag of certainty, we continue to double down on what we did last time. When we demand certainty, we demand old work. As a company, you can have too much “certainty.”

When you flog the teams because they have too much uncertainty, you flog out all the novelty.

What if you start the design review with the question “What’s novel about this project?” And when the team says there’s nothing novel, what if you say “Well, go back to the drawing board and come back with some novelty.”? If you seek out novelty instead of squelching it, you’ll get more novelty. That’s a rule, though not limited to novelty.

A bias toward best practices is a bias toward old work. And the belief underpinning those biases is the belief that the Universe is static. And the one thing the Universe doesn’t like to be called is static. The Universe prides itself on its dynamic character and unpredictable nature. And the Universe isn’t above using karma to punish those who call it names.

“Stonecold certainty” by philwirks is licensed under CC BY-ND 2.0

When your company looks in the mirror, what does it see?

There are many types of companies, and it can be difficult to categorize them. And even within the company itself, there is disagreement about the company’s character. And one of the main sources of disagreement is born from our desire to classify our company as the type we want it to be rather than as the type that it is.

There are many types of companies, and it can be difficult to categorize them. And even within the company itself, there is disagreement about the company’s character. And one of the main sources of disagreement is born from our desire to classify our company as the type we want it to be rather than as the type that it is.

Here’s a process that may bring consensus to your company.

For all the people on the payroll, assign a job type and tally them up for the various types. If most of your people work in finance, you work for a finance company. If most work in manufacturing, you work for a manufacturing company. The same goes for sales, engineering, customer service, consulting. Write your answer here __________.

For all the company’s profits, assign a type and roll up the totals. If most of the profit is generated through the sale of services, you work for a service company. If most of the profit is generated by the sale of software, you work for a software company. If hardware generates profits, you work for a hardware company. If licensing of technology generates profits, you work at a technology company. Which one fits your company best? Write your answer here _________.

For all the people on the payroll, decide if they work to extend and defend the core offerings (the things that you sell today) or create new offerings in new markets that are sold to new customers. If most of the people work on the core offerings, you work for a low-growth company. If most of the people work to create new offerings (non-core), you work for a high-growth company. Which fits you best – extend and defined the core / low-growth or new offerings / high growth? Write your answer here __________ / ___________.

Now, circle your answers below.

We are a (finance, manufacturing, sales, engineering, customer service, consulting) company that generates most of its profits through the sale of (services, hardware, software, technology). And because most of our people work to (extend and defend the core, create new offerings), we are a (low, high) growth company.

To learn what type of company you work for, read the sentences out loud.

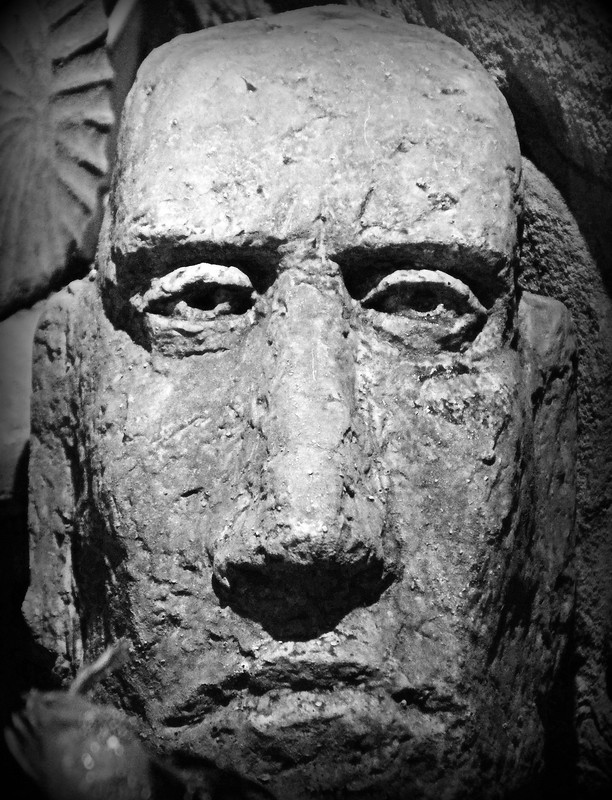

“Grace – Mirror” by phil41dean is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski