Archive for the ‘Top Line Growth’ Category

How To Make Progress

Improvement is progress. Improvement is always measured against a baseline, so the first thing to do is to establish the baseline, the thing you make today, the thing you want to improve. Create an environment to test what you make today, create the test fixtures, define the inputs, create the measurement systems, and write a formal test protocol. Now you have what it takes to quantify an improvement objectively. Test the existing product to define the baseline. No, you haven’t improved anything, but you’ve done the right first thing.

Improvement is progress. Improvement is always measured against a baseline, so the first thing to do is to establish the baseline, the thing you make today, the thing you want to improve. Create an environment to test what you make today, create the test fixtures, define the inputs, create the measurement systems, and write a formal test protocol. Now you have what it takes to quantify an improvement objectively. Test the existing product to define the baseline. No, you haven’t improved anything, but you’ve done the right first thing.

Improving the right thing to make progress. If the problem invalidates the business model, stop what you’re doing and solve it right away because you don’t have a business if you don’t solve it. Any other activity isn’t progress, it’s dilution. Say no to everything else and solve it. This is how rapid progress is made. If the customer won’t buy the product if the problem isn’t solved, solve it. Don’t argue about priorities, don’t use shared resources, don’t try to be efficient. Be effective. Do one thing. Solve it. This type of discipline reduces time to market. No surprises here.

Avoiding improvement of the wrong thing to make progress. For lesser problems, declare them nuisances and permit yourself to solve them later. Nuisances don’t have to be solved immediately (if at all) so you can double down on the most important problems (speed, speed, speed). Demoting problems to nuisances is probably the most effective way to accelerate progress. Deciding what you won’t do frees up resources and emotional bandwidth to make rapid progress on things that matter.

Work the critical path to make progress. Know what work is on the critical path and what is not. For work on the critical path, add resources. Pull resources from non-critical path work and add them to the critical path until adding more slows things down.

Eliminate waiting to make progress. There can be no progress while you wait. Wait for a tool, no progress. Wait for a part from a supplier, no progress. Wait for raw material, no progress. Wait for a shared resource, no progress. Buy the right tools and keep them at the workstations to make progress. Pay the supplier for priority service levels to make progress. Buy inventory of raw materials to make progress. Ensure shared resources are wildly underutilized so they’re available to make progress whenever you need to. Think fire stations, fire trucks, and firefighters.

Help the team make progress. As a leader, jump right in and help the team know what progress looks like. Praise the crudeness of their prototypes to help them make them cruder (and faster) next time. Give them permission to make assumptions and use their judgment because that’s where speed comes from. And when you see “activity” call it by name so they can recognize it for themselves, and teach them how to turn their effort into progress.

Be relentless and respectful to make progress. Apply constant pressure, but make it sustainable and fun.

Image credit — Clint Mason

Resurrecting Manufacturing Through Product Simplification

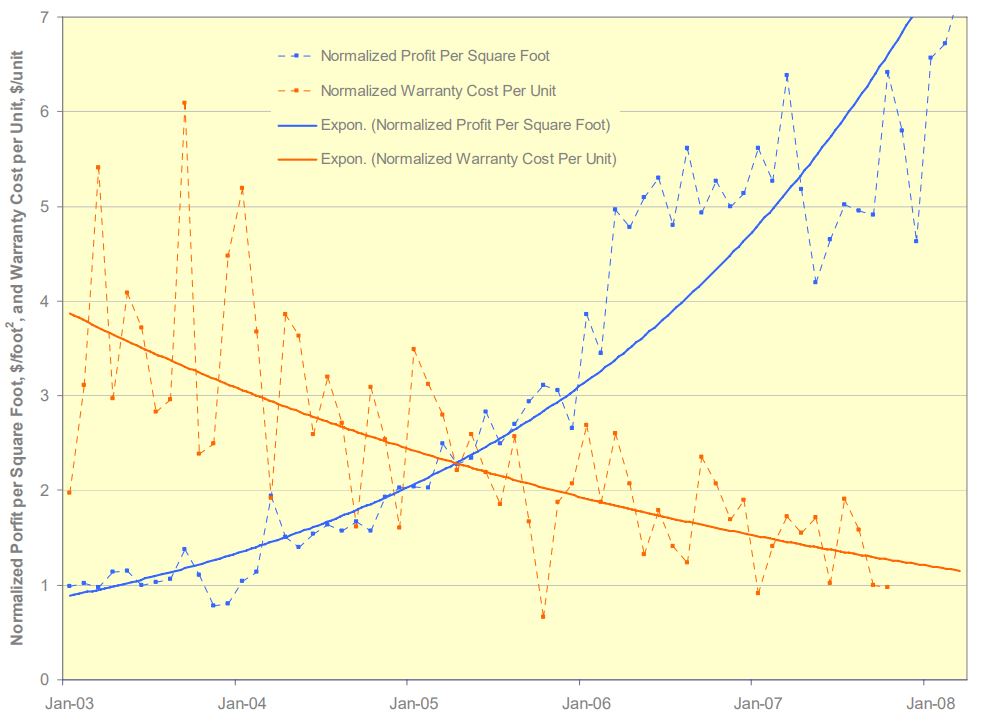

Product simplification can radically improve profits and radically improve product robustness. Here’s a graph of profit per square foot ($/ft^2) which improved by a factor of seven and warranty cost per unit ($/unit), a measure of product robustness), which improved by a factor of four. The improvements are measured against the baseline data of the legacy product which was replaced by the simplified product. Design for Assembly (DFA) was used to simplify the product and Robust Design methods were used to reduce warranty cost per unit.

I will go on record that everyone will notice when profit per square foot increases by a factor of seven.

And I will also go on record that no one will believe you when you predict product simplification will radically improve profit per square foot.

And I will go on record that when warranty cost per unit is radically reduced, customers will notice. Simply put, the product doesn’t break and your customers love it.

But here’s the rub. The graph shows data over five years, which is a long time. And if the product development takes two years, that makes seven long years. And in today’s world, seven years is at least four too many. But take another look at the graph. Profit per square foot doubled in the first two years after launch. Two years isn’t too long to double profit per square foot. I don’t know of a faster way, More strongly, I don’t know of another way to get it done, regardless of the timeline.

I think your company would love to double the profit per square foot of its assembly area. And I’ve shown you the data that proves it’s possible. So, what’s in the way of giving it a try?

For the details about the work, here’s a link – Systematic DFMA Deployment, It Could Resurrect US Manufacturing.

Effectiveness Before Efficiency

Efficient – How do we do more projects with fewer people?

Efficient – How do we do more projects with fewer people?

Effective – Let’s choose the right project.

Would you rather do more projects that miss the mark or fewer that excite the customer?

Efficient – How do we finish the project faster?

Effective – Let’s fully staff the project.

Would you rather burn out the project team or deliver on what the customer wants?

Efficient – How do we reduce product cost by 5%?

Effective – Let’s make customers’ lives easier.

Would you rather reduce the cost or delight the customer?

Efficient – How can we go faster?

Effective – Let’s get it right.

Would you rather go fast and break things or get it right for the customer?

Efficient – How many projects can we run in parallel?

Effective – Let’s fully staff the most important projects.

Would you rather get halfway through four projects or complete two?

Efficient – How do we make progress on as many tasks as possible?

Effective – Let’s work on the critical path.

Would you rather work on things that don’t matter or nail the things that do?

Efficient – How can we complete the most tasks?

Effective – Let’s work on the hardest thing first.

Would you rather learn the whole thing won’t work before or after you waste time on the irrelevant?

If there’s a choice between efficiency and effectiveness, I choose effectiveness.

Image credit — Antarctica Bound

How To Elevate The Work

If you want people to work together, give them a reason. Tell them why it’s important to the company and their careers.

If you want people to work together, give them a reason. Tell them why it’s important to the company and their careers.

If you want people to change things, change how they interact. Eliminate leaders from some, or all, of the meetings. Demand they set the approach. Give them control over their destiny. Make them accountable to themselves. Give them what they ask for.

If you want to create a community, let something bad happen. The right people will step up and the experts will band together around the common cause. And after they put the train back on the track, they’ll be ready and willing for a larger challenge.

If you want the team to make progress, make it easy for them to make progress. Stop the lesser projects so they can focus. Cancel meetings so they can focus. Give them clear guidance so they can focus on the right work. Give them the tools, time, training, and a teacher. Ask them how to make their work easier and listen.

If you want the team to finish projects faster, ask them to focus on effectiveness at the expense of efficiency.

If you want the organization to be more flexible, create the causes and conditions for trust-based relationships to develop. When people work shoulder-to-shoulder on a difficult project trust is created. And for the remainder of their careers, they will help each other. They will help each other despite the formal organizational structure. They will help each other despite their formal commitments. They will help each other despite the official priorities.

If you want things to change, don’t try to change people. Move things out of the way so they can make it happen.

Image credit — frank carman

What do you do when you’ve done it before?

COPYRIGHT GEOFF HENSON

If you’ve done it before, let someone else do it.

If you’ve done it before, teach someone else to do it.

If you’ve done it before, do it in a tenth of the time.

Do it differently just because you can.

Do it backward. That will make you smile.

Do it with your eyes closed. That will make a statement.

Do its natural extension. That could be fun.

Do the opposite. Then do its opposite. You’ll learn more.

Do what they should have asked for. Life is short.

Do what scares them. It’s sure to create new design space.

Do what obsoletes your most profitable offering. Wouldn’t you rather be the one to do it?

Do what scares you. That’s sure to be the most interesting of all.

Image credit — Geoff Henson

Measureable or magical?

We all have to-do lists. We add things and we check them off. This list grows and shrinks. We judge ourselves negatively when we check off fewer than expected and positively when we check off more than that. But what’s the right number of completed tasks for us to feel good? How many completed tasks is enough?

We all have to-do lists. We add things and we check them off. This list grows and shrinks. We judge ourselves negatively when we check off fewer than expected and positively when we check off more than that. But what’s the right number of completed tasks for us to feel good? How many completed tasks is enough?

If you complete one task per week that saves $5000, is that enough? Is it enough to complete fifty tasks per year? If you create the conditions that make possible a new product line that delivers $1B over three years, but you do that only once every five years, is that enough? Is it enough to do just that one right thing over five years? What does it look like to others when you complete one exceptionally meaningful task every five years? I think it looks like most of the time you are doing very little.

Sometimes you complete small things and sometimes you don’t. And sometimes you learn what doesn’t work and that’s the completed task. And sometimes there are long stretches where nothing is accomplished until you create something magical. Counting tasks is no way to go through life.

But counting and measuring is all the rage. Look at your yearly goals. Do ten of these. Run six of those. Complete twelve of the other. Why do we think we can predict what we should do next year? Even sillier, do we really believe we know how many of these, those, and the others we will be able to get done next year? C’mon. Really?

What if all this counting prevents us from imagining the future? And what if our unhealthy fascination with measuring blocks us from creating it?

If it’s all about the measurable, there’s no room for the Magical.

Why not make some room for the Magical?

Image credit — Philip McErlean

Pro Tips for New Product Development Projects

Do the project right or do the right project – which would you choose?

Do the project right or do the right project – which would you choose?

If you improve time to market, the only thing that improves is time to market. How do you feel about that?

Customers pay for things that make their lives easier. Time to market doesn’t do that.

There’s no partial credit with new product development projects. If the product isn’t 100% ready for sale, it’s 0% ready.

If you made 1/8th progress on 8 projects, you made zero progress. But you did consume valuable resources.

If you made 100% progress on one project, you made progress.

When you have too many projects, you get too few done.

If you don’t know how many projects your company has, you have too many.

Would you rather choose the right project and run it inefficiently or choose the wrong project and run it efficiently?

When you choose the wrong project but run it efficiently, that’s called efficient ineffectiveness.

You can save several weeks making sure you choose the right project by starting the project too soon and running the wrong one for two years.

If your projects are slow, it’s likely the support functions are too highly utilized. Add capacity to keep their peak utilization below 85%.

When shared resources are sized appropriately, they’re underutilized most of the time. Think fire station and firefighters – when there’s a fire they respond quickly, and when there’s no fire they improve their skills so they can fight the next one better than the last.

If your projects are slow, check to see if you have resources on the critical path that work part-time. Part-time resources support multiple projects and don’t work full-time on your project. And you can’t control when they work on your project. There’s no place for that on the critical path.

If you’re thinking about using part-time resources on the critical path, don’t.

Know where the novelty is and work that first. And before you can work on the novelty you’ve got to know where it is.

You can have too little novelty, meaning the new product is so much like the old one there’s no need to launch it. Mostly, though, projects have too much novelty.

If you are working on a clean-sheet design, there is no such thing. There are no green-field projects. All projects are brown-field projects. It’s just that some are browner than others.

Novelty generates problems and problems take three times longer to solve than anyone thinks. To reduce the number of problems, declare as many as possible as annoyances. Unlike problems, annoyances don’t have to be solved by the project. Remember, it’s okay to save some work for the next project.

Even though you have a product development process, that process is powered by people. People make it work and people make it not work. If you get one thing right, get the people part right.

Image credit – claudia gabriela marques

Working In Domains of High Uncertainty

X: When will you be done with the project?

X: When will you be done with the project?

Me: This work has never been done before, so I don’t know.

X: But the Leadership Team just asked me when the project will be done. So, what should I say?

Me: Since nothing has changed since the last time you asked me, I still don’t know. Tell them I don’t know.

X: They won’t like that answer.

Me: They may not like the answer, but it’s the truth. And I like telling the truth.

X: Well, what are the steps you’ll take to complete the project?

Me: All I can tell you is what we’re trying to learn right now.

X: So all you can tell me is the work you’re doing right now?

Me: Yes.

X: It seems like you don’t know what you’re doing.

Me: I know what we’re doing right now.

X: But you don’t know what’s next?

Me: How could I? If this current experiment goes up in smoke, the next thing we’ll do is start a different project. And if the experiment works, we’ll do the next right thing.

X: So the project could end tomorrow?

Me: That’s right.

X: Or it could go on for a long time?

Me: That’s right too.

X: Are you always like this?

Me: Yes, I am always truthful.

X: I don’t like your answers. Maybe we should find someone else to run the project.

Me: That’s up to you. But if the new person tells you they know when the project will be done, they’re the wrong person to run the project. Any date they give you will be a guess. And I would not want to be the one to deliver a date like that to the Leadership Team.

X: We planned for the project to be done by the end of the year with incremental revenue starting in the first quarter of next year.

Me: Well, the project work is not bound by the revenue plan. It’s the other way around.

X: So, you don’t care about the profitability of the company?

Me: Of course I care. That’s why we chose this project – to provide novel customer value and sell more products.

X: So the project is intended to deliver new value to our customers?

Me: Yes, that’s how the project was justified. We started with an important problem that, if solved, would make them more profitable.

X: So you’re not just playing around in the lab.

Me: No, we’re trying to solve a customer problem as fast as we can. It only looks like we’re playing around.

X: If it works, would our company be more profitable?

Me: Absolutely.

X: Well, how can I help?

Me: Please meet with the Leadership Team and thank them for trusting us with this important project. And tell them we’re working as fast as we can.

Image credit – Florida Fish and Wildlife

X: Me: format stolen from Simon Wardley (@swardley). Thank you, Simon.

Too Much of a Good Thing

Product cost reduction is a good thing.

Product cost reduction is a good thing.

Too much focus on product cost reduction prevents product enhancements, blocks new customer value propositions, and stifles top-line growth.

Voice of the Customer (VOC) activities are good.

Because customers don’t know what’s possible, too much focus on VOC silences the Voice of the Technology (VOT), blocks new technologies, and prevents novel value propositions. Just because customers aren’t asking for it doesn’t mean they won’t love it when you offer it to them.

Standard work is highly effective and highly productive.

When your whole company is focused on standard work, novelty is squelched, new ideas are scuttled, and new customer value never sees the light of day.

Best practices are highly effective and highly productive.

When your whole company defaults to best practices, novel projects are deselected, risk is radically reduced (which is super risky), people are afraid to try new things and use their judgment, new products are just like the old ones (no sizzle), and top-line growth is gifted to your competitors.

Consensus-based decision-making reduces bad decisions.

In domains of high uncertainty, consensus-based decision-making reduces projects to the lowest common denominator, outlaws the use of judgment and intuition, slows things to a crawl, and makes your most creative people leave the company.

Contrary to Mae West’s maxim, too much of a good thing isn’t always wonderful.

Image credit — Krassy Can Do It

The Next Evolution of Your Success

New ways to work are new because they have not been done before.

New ways to work are new because they have not been done before.

How many new ways to work have you demonstrated over the last year?

New customer value is new when it has not been shown before.

What new customer value have you demonstrated over the last year?

New ways to deliver customer value are new when you have not done it that way before.

How much customer value have you demonstrated through non-product solutions?

The success of old ways of working block new ways.

How many new ways to work have been blocked by your success?

The success of old customer value blocks new customer value.

How much new customer value has been blocked by your success with old customer value?

The success of tried and true ways to deliver customer value blocks new ways to deliver customer value.

Which new ways to deliver unique customer value have been blocked by your success?

Might you be more successful if you stop blocking yourself with your success?

How might you put your success behind you and create the next evolution of your success?

Image credit — Andy Morffew

If you want to change things, do a demo.

When you demo something new, you make the technology real. No longer can they say – that’s not possible.

When you demo something new, you make the technology real. No longer can they say – that’s not possible.

When you demo something new, you help people see what it is and what it isn’t. And that brings clarity.

When you demo something new, people take sides. And that says a lot about them.

When you demo something new, be prepared to demo it again. It takes time for people to internalize new concepts.

When someone asks you to repeat the demo so others can see it, it’s a sign there’s something interesting about the demo. Repeat it.

When someone calls out fault with a minor element of the demo, they also reinforce the strength of the main elements.

When you demo something new and it works perfectly, you should have demo’d it sooner.

When the demo works perfectly, you’re not trying hard enough.

When you demo something new, there is no way to predict the action items spawned by the demo. In fact, the reason to do the demo is to learn the next action items.

When you demo something new, make the demo short so the conversation can be long.

When you demo something new, shut your mouth and let the demo do the talking.

When you demo something new, keep track of the questions that arise. Those questions will inform the next demo.

When you demo something new and it’s misunderstood, congratulations. You’ve helped the audience loosen their thinking.

If you want to change people’s thinking, do a demo.

Image credit – Ralf Steinberger

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski