Archive for the ‘Technology’ Category

The human side of Technology

Technology has strong character traits; it has wants and desires; it plans for the future. It’s alive.

Technology has strong character traits; it has wants and desires; it plans for the future. It’s alive.

Technology continually tries to reinvent itself. And like rust, it never sleeps – it continually thinks, schemes, and plans how to do more with less (or less with far less). That’s Technology’s life dream, its prime directive – more with less. All day, every day it strives, reaches, and writhes toward more with less.

Technology needs our help along its journey. To do this we must understand its life experiences, understand its emotional state, and listen when it talks of the future. Like with a good friend, listening is important.

Technology has several important character traits which govern how it goes about its life’s work. Habitually, it likes to focus its energy on one a single subsystem and reinvents it, where the reinvented subsystem then puts strain on the others. It is this mismatch in capability among the subsystems that Technology uses to fuel innovation on the next subsystem. Its work day goes like this: innovate on a subsystem, create strife among the others, and repeat.

Technology likes to continually increase its flexibility. It feels better when it can stretch, bend, twist, and contort. It likes to develop pivot points, hinges, and rubbery algorithms that adjust to unexpected inputs and create novel outputs. Ultimately Technology wants to self-design and self-configure, but that’s down the road.

Technology likes to get into the details – the deeper the better. To do this it gets small. Here’s its rationale: small changes at the molecular or atomic levels roll up to big changes at the system level. A small change multiplied by Avogadro’s number makes for a big lever. Technology understands this.

Technology is frugal, not wasteful in any way, especially when it comes to energy. Its best party trick is to shorten energy flow paths. The logic: shorter energy paths result in less loss and a simpler product. You’ll see this in its next round of work in energy efficiency where it will move subsystems closer to each other to radically improve efficiency and radically reduce product complexity.

Technology knows where it wants to go, and has its favorite ways to get there. Our innovation engines will be more productive if they’re informed by its character.

(Special thanks to Victor Fey for teaching me about Technology’s character traits, which he calls lines of evolution.)

Coaxing out of the weeds.

Doing new is difficult and scary. For safety, we create complexity and hide behind it; we swim for the weeds; we dive for the details. (At least we’ll come across as knowledgeable about something when we bury our heads in details.) All of this so we can look smart and feel safe.

Doing new is difficult and scary. For safety, we create complexity and hide behind it; we swim for the weeds; we dive for the details. (At least we’ll come across as knowledgeable about something when we bury our heads in details.) All of this so we can look smart and feel safe.

But with new stuff, looking smart and feeling safe are not valid. With new, we don’t know; we’re not smart (yet); there’s no reason to feel safe. (Don’t try, it’s too slow.)

It takes focus and compassion to coax people out of the weeds and help them feel safe. Focus is needed to keep the end game in mind, to constantly keep context in the forefront (why are we here?), to maintain the right compass heading (into the wind). Compassion is needed to make “I don’t know” feel safe. To start, explain the deal: “new” and “I don’t know” are inseparable, a matched set. Like your best pair of wool socks, left without right doesn’t work. If that’s insufficient, tell them if was easy you’d have asked someone else to do it.

Day-to-day, it’s difficult to maintain focus and compassion. I find it helpful to remember it’s natural to seek safety in the weeds. We all do it. Keep that in mind while you do new as fast as you can.

For innovation, look inside.

Everyone is dissatisfied with the pace of innovation – solutions that change the game don’t come fast enough. We look to the environment, and assign blame. We blame the tools, the process, the organization structure, and the technology itself. But the blame is misplaced. It is the innovators that govern the pace of innovation.

Everyone is dissatisfied with the pace of innovation – solutions that change the game don’t come fast enough. We look to the environment, and assign blame. We blame the tools, the process, the organization structure, and the technology itself. But the blame is misplaced. It is the innovators that govern the pace of innovation.

It certainly isn’t the technology – the solutions already exist; they’re patiently waiting for us, waiting for us to find them. We just have to look. The technology knows what it will be when it grows up: the path is clear. Put simply, we must break through our unwillingness to look. We must look harder, deeper, and more often. We must redefine our self-set limits, and look under the rocks of our successes and beyond our best work.

To increase the pace and quality of innovation, we must look inside.

a

a

p.s. I’m holding a half-day workshop on how to implement systematic cost savings through product design on June 13 in Providence RI as part of the International Forum on DFMA — here’s the link. I hope to see you there.

I don’t know the question, but the answer is jobs.

Some sobering facts: (figure and facts from Matt Slaughter)

Some sobering facts: (figure and facts from Matt Slaughter)

- During the Great Recession, US job loss (peak to trough) was 8.4 million payroll jobs were lost (6.1%) and 8.5 million private-sector jobs (7.3%).

- In Sept. 2010 there were 108 million U.S. private-sector payroll jobs, about the same as in March 1999.

- It took 48 months to regain the lost 2.0% of jobs in the 2001 recession. At that rate, the U.S. would again reach 12/07 total payroll jobs around January 2020.

The US has a big problem. And I sure as hell hope we are willing do the hard work and make the hard sacrifices to turn things around.

To me it’s all about jobs. To create jobs, real jobs, the US has got to become a more affordable place to invent, design, and manufacture products. Certainly modified tax policies will help and so will trade agreements to make it easier for smaller companies to export products. But those will take too long. We need something now.

To start, we need affordability through productivity. But not the traditional making stuff productivity, we need inventing and designing productivity.

Here’s the recipe: Invent technology in-country, design and develop desirable products in-country (products that offer real value, products that do something different, products that folks want to buy), make the products in-country, and sell them outside the country. It’s that straightforward.

To me invention/innovation is all about solving technical problems. Solving them more productively creates much needed invention/innovation productivity. The result: more affordable invention/innovation.

To me design productivity is all about reducing product complexity through part count reduction. For the same engineering hours, there are few things to design, fewer things to analyze, fewer to transition to manufacturing. The result: more affordable design.

Though important, we can’t wait for new legislation and trade agreements. To make ourselves more affordable we need to increase productivity of our invention/innovation and design engines while we work on the longer term stuff.

If you’re an engineering leader who wants more about invention/innovation and or design productivity, send me an email at

and use the subject line to let me know which you’re interested in. (Your contact information will remain confidential and won’t be shared with anyone. Ever.)

Together we can turn around the country’s economy.

Our Misguided Focus on Patents

Is it patented? Can we patent that? We need a @#!$%& patent and we need it now! You hear that a lot these days. Everyone wants to be part of the new economy, the thinking economy, and patents are the key, right? No.

Is it patented? Can we patent that? We need a @#!$%& patent and we need it now! You hear that a lot these days. Everyone wants to be part of the new economy, the thinking economy, and patents are the key, right? No.

Patents are the results of something – good, old-fashioned innovation. The big mistake companies make is to focus directly on patents instead of focusing on innovation which can then be patented. Sounds like a subtle difference, but it’s as subtle as the difference between lightning and lightning bug. (Stolen from Mark Twain.)

Patents are the currency of innovation, not the innovation itself, just as our paper money is the currency for wealth, and not the gold reserve itself. We use paper money to stand for the gold, but, implicitly, there’s wealth backing it up. Just as it’s misguided for a country to print money without something to back it up (strong gold reserves), it’s misguided for a company to create patents without something to back them up – innovative technologies, technologies that make a difference to the customer.

Innovation is the gold that backs up patents, the currency of innovation.

Would you rather have lots of paper money and no gold, or lots of gold that allows you to print lots of money? We get this one wrong when we focus on paper patents instead of golden innovation. Why do we mess it up? Because printing money and filing patents are easy, and digging gold and doing innovation are hard. Patents are fast and innovation is slow. Companies want the free lunch, there’s no such thing.

What to do when there are no patents? Do innovation. What to do when there is no time to do innovation? Do innovation. What to do when there is no money to do innovation? Do innovation. What to do? Do innovation.

The road to a full portfolio of innovative technologies is a long one, but it’s paved with gold.

Discontinuous Improvement at the Expense of Continuous Improvement

Five percent here, three percent there. I’m tired as hell of continuous improvement. Sure there’s a place for it, but it shouldn’t be the only type of work we do. But, unfortunately, that’s just what’s happened in manufacturing. To secure the balance sheet, the pendulum swung too far toward continuous improvement. Just look at what we’re writing about – the next low cost country, shorter lead times, how to be profitable where there’s no profit to be had. Those topics scream continuous improvement – take nickels and dimes out of processes to increase profits. But there’s a dark side to all this focus on continuous improvement. It has created a big problem: it has come at the expense of discontinuous improvement.

Five percent here, three percent there. I’m tired as hell of continuous improvement. Sure there’s a place for it, but it shouldn’t be the only type of work we do. But, unfortunately, that’s just what’s happened in manufacturing. To secure the balance sheet, the pendulum swung too far toward continuous improvement. Just look at what we’re writing about – the next low cost country, shorter lead times, how to be profitable where there’s no profit to be had. Those topics scream continuous improvement – take nickels and dimes out of processes to increase profits. But there’s a dark side to all this focus on continuous improvement. It has created a big problem: it has come at the expense of discontinuous improvement.

Continuous improvement is a philosophy of minimization with a focus on cost and waste reduction, while discontinuous improvement is a philosophy of maximization with a focus on creation of new markets through product innovation. As of late, we’ve minimized waste at the expense of invention and innovation. I propose we flip this on its head and maximize through discontinuous improvement at the expense of continuous improvement. That’s right; I said do less lean and Six Sigma.

But we must ask ourselves if we’re capable of doing discontinuous improvement. Remember, we ignored or dismantled our innovation engines over the last years. And what about our big thinkers, our creative thinkers, our innovators? Do they still work for us, or have they just stopped talking about big ideas? I urge you to answer that question because your next actions depend on it.

If your innovative thinkers are gone, go out and hire the best you can find ASAP. If you were fortunate enough to retain your big thinkers, congratulations. Now it’s time to get the band back together, but first you’ve got to do some reconnaissance to ferret them out of their hiding places. Once you find them, invite them to a nice lunch – the nicer the better. Don’t push too hard at lunch, just start to get reacquainted. In time you’ll get to talk about their ideas on new technologies and how to create new markets.

It will be difficult to get your company swing the pendulum away from continuous improvement, but you must try. Without discontinuous improvement your company will be destined to wrestle for nickels using lean and Six Sigma.

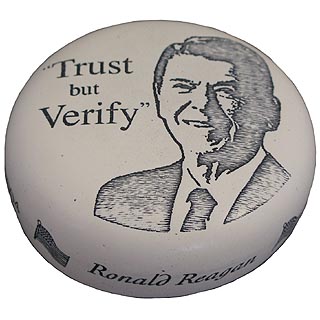

With Innovation, It’s Trust But Verify.

Your best engineer walks into your office and says, “I have this idea for a new technology that could revolutionize our industry and create new markets, markets three times the size of our existing ones.” What do you do? What if, instead, it’s a lower caliber engineer that walks into your office and says those same words? Would you do anything differently? I argue you would, even though you had not heard the details in either instance. I think you’d take your best engineer at her word and let her run with it. And, I think you’d put less stock in your lesser engineer, and throw some roadblocks in the way, even though he used the same words. Why? Trust.

Your best engineer walks into your office and says, “I have this idea for a new technology that could revolutionize our industry and create new markets, markets three times the size of our existing ones.” What do you do? What if, instead, it’s a lower caliber engineer that walks into your office and says those same words? Would you do anything differently? I argue you would, even though you had not heard the details in either instance. I think you’d take your best engineer at her word and let her run with it. And, I think you’d put less stock in your lesser engineer, and throw some roadblocks in the way, even though he used the same words. Why? Trust.

Innovation is largely a trust-based sport. We roll the dice on folks that have already put it on the table, and, conversely, we raise the bar on those that have not yet delivered – they have not yet earned our trust. Seems rational and reasonable – trust those who have earned it. But how did they earn your trust the first time, before they delivered? Trust.

There is no place for trust in the sport of innovation. It’s unhealthy. Ronald Reagan had it right:

Trust, but verify.

As we know, he really meant there was no place for trust in his kind of sport. Every action, every statement had to be verified. The consequences so cataclysmic, no risk could be tolerated. With innovation consequences are not as severe, but they are still substantial. A three year, multi-million (billion?) dollar innovation project that returns nothing is substantial. Why do we tolerate the risk that comes with our trust-based approach? I think it’s because we don’t think there’s a better way. But there is. What we need is some good, old-fashioned verification mixed in with our innovation.

When the engineer comes into your office and says she can reinvent your industry, what do you ask yourself? What do you want to verify? You want to know if the new idea is worth a damn, if it will work, if there are fundamental constraints in the way. But, unfortunately for you, verification requires knowledge of the physics, and you’re no physicist. However, don’t lose hope. There are two simple tactics, non-technical tactics, to help with this verification business.

First – ask the engineers a simple question, “What conflict is eliminated with the new technology?” Good, innovative technologies eliminate fundamental, long standing conflicts. These long standing conflicts limit a technology in a way that is so fundamental engineers don’t even know they exist. When a fundamental conflict is eliminated, long held “design tradeoffs” no longer apply, and optimizing is replaced by maximizing. With optimizing, one aspect of the design is improved at the expense of another. With maximizing, both aspects of the design are improved without compromise. If the engineers cannot tell you about the conflict they’ve eliminated, your trust has not been sufficiently verified. Ask them to come back when they can answer your question.

Second – when they come back with their answer, it will be too complex to be understood, even by them. Tell them to come back when they can describe the conflict on a single page using a simple block diagram, where the blocks, labeled with everyday nouns, represent parts of the design intimately involved with the conflict, and the lines, labeled with everyday verbs, represent actions intimately involved with the conflict. If they can create a block diagram of the conflict, and it makes sense to you, your trust has been sufficiently verified. (For a post with a more detailed description of the block diagrams, click on “one page thinking” in the Category list.)

Though your engineers won’t like it at first, your two-pronged verification tactics will help them raise their game, which, in turn, will improve the risk/reward ratio of your innovation work.

Engineering your way out of the recession

Like you, I have been thinking a lot about the recession. We all want to know how to move ourselves to the other side, where things are somewhat normal (the old normal, not the new one). Like usual, my mind immediately goes to products. To me, having the right products is vital to pulling ourselves out of this thing. There is nothing novel in this thinking; I think we all agree that products are important. But, there are two follow-on questions that are important. First, what makes products “right” to move you quickly to the other side? Second, do you have the capability to engineer the “right” products?

Like you, I have been thinking a lot about the recession. We all want to know how to move ourselves to the other side, where things are somewhat normal (the old normal, not the new one). Like usual, my mind immediately goes to products. To me, having the right products is vital to pulling ourselves out of this thing. There is nothing novel in this thinking; I think we all agree that products are important. But, there are two follow-on questions that are important. First, what makes products “right” to move you quickly to the other side? Second, do you have the capability to engineer the “right” products?

The first question – what makes products “right” for these times? Capacity is important to understanding what makes products right. Capacity utilization is at record lows with most industries suffering from a significant capacity glut. With decreased sales and idle machines, customers are no longer interested in products that improve productivity of their existing product lines because they can simply run their idle machines more. And, they are not interested in buying more capacity (your products) at a reduced price. They will simply run their idle machines more. You can’t offer an improvement of your same old product that enables customers to make their same old products a bit faster and you can’t offer them your same old products at a lower price. However, you can sell them products that enable them to capture business they currently do not have. For example, enable them to manufacture products that their idle machines CANNOT make at all. To do that means your new products must do something radically different than before; they must have radically improved functionality or radically new features. This is what makes products right for these times.

On to the second question – do you have the capability to engineer the right products? Read the rest of this entry »

Can CEOs meaningfully guide technology work?

Leading, shaping, and guiding technology work is hard, even for technologists who spend all day doing it. So, it seems the all-too-busy CEOs don’t stand a chance at effectively shaping their companies’ technical work. And it’s not just the non-technologist CEOs who have a problem; the technologist CEOs also have a problem, as they don’t have sufficient time to dig deeply into the details or stay current on the state-of-the-art. So, as a CEO, technologist or not, it is difficult to meaningfully lead, shape, and guide technical work.

Leading, shaping, and guiding technology work is hard, even for technologists who spend all day doing it. So, it seems the all-too-busy CEOs don’t stand a chance at effectively shaping their companies’ technical work. And it’s not just the non-technologist CEOs who have a problem; the technologist CEOs also have a problem, as they don’t have sufficient time to dig deeply into the details or stay current on the state-of-the-art. So, as a CEO, technologist or not, it is difficult to meaningfully lead, shape, and guide technical work.

So why is this technology stuff so hard to shape and guide? Well, here are a few reasons: technologies have their own set of arcane languages, each with many dialects (and no dictionary); they have their own technology-centric acronyms that technologists mix and match as they see fit; and they are full of long-forgotten formulae. And these formulae are composed of strange math shapes and symbols. And, as if to elevate confusion to stratospheric levels, the math symbols are Greek letters. So, literally, this technology stuff is written in Greek. So what’s an all-too-busy CEO to do? Read the rest of this entry »

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski