Archive for the ‘Seeing Things As They Are’ Category

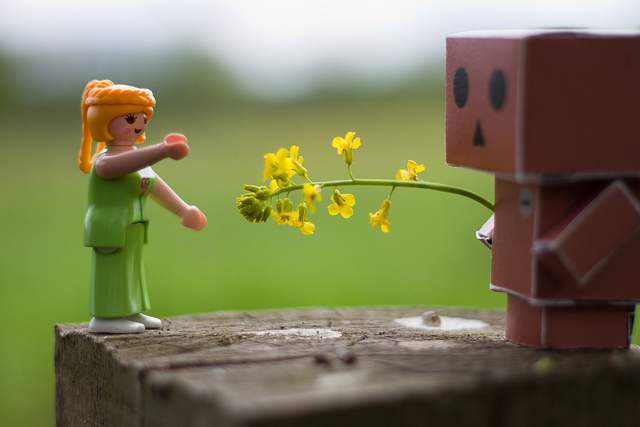

There is no control. There is only trust.

Control strategies don’t work, but trust strategies do.

Control strategies don’t work, but trust strategies do.

Nothing goes as planned. Trying to control things tightly is wasteful. It takes too much energy to batten down all the hatches and keep them that way every-day-all-day. Maybe no water gets in, but the crew doesn’t get enough oxygen and their brains wither.

Trust on the other hand, is flexible and far more efficient. It takes little energy to hire a pro, give them the right task and get out of the way. And with the best pros it requires even less energy because the three-step becomes a two-step – hire them and get out of the way.

When both hands are continuously busy pulling the levers of contingency plans there are no hands left to point toward the future. When both arms are clinging onto the artificial schedule of the project plan there are no arms left to conduct the orchestra. Control strategies make sure even the piccolo plays the right notes at the right time, while trust strategies let the violins adjust based on their ear and intuition and even let the conductors write their own sheet music.

Control is an illusion, but trust is real. The best statistical analyses are rearward-looking and provide no control in a changing environment. (You can’t drive a car by looking in the rear view mirror.) Yet, that’s the state-of-the-art for control strategies – don’t change the inputs, don’t change the process and we’ll get what we got last time. That’s not control. That’s self-limiting.

Trust is real because people and their relationships are real. Trust is a contract between people where one side expects hard work and good judgment and the other side expects to be challenged and to be given the flexibility to do the work as they see fit. Trust-based systems are far more adaptable than if-then control strategies. No control algorithm can effectively handle unanticipated changes in input conditions or unplanned drift in decision criteria, but people and their judgement can. In fact, that’s what people are good at, and they enjoy doing it. And that’s a great recipe for an engaged work force.

Control strategies are popular because they help us believe we have control. And they’re ineffective for the same reason. Trust strategies are not popular because they acknowledge we have no real control and rely on judgment. And that’s why they’re effective.

When control strategies fail, trust strategies are implemented to save the day. When the wheels fall off a project, the best pro in the company is brought in to fix what’s broken. And the best pro is the most trusted pro. And their charge – Tell us what’s wrong (Use your judgement.), tell us how you’re going to fix it (Use your best judgement for that.) and tell us what you need to fix it. (And use your best judgement for that, too.)

In the end, trust trumps control. But only after all other possibilities are exhausted.

Image credit – Dobi.

All Your Mental Models are Obsolete

Even after playing lots of tricks to reduce its energy consumption, our brains still consume a large portion of the calories we eat. Like today’s smartphones it’s computing power is too big for it’s battery so its algorithms conserve every chance they get. One of its go-to conservation strategies is to make mental models. The models capture the essence of a system’s behavior without the overhead of retaining all the details of the system.

And as the brain goes about its day it tries to fit what it sees to its portfolio of mental models. Because mental models are so efficient, to save juice the brain is pretty loose with how it decides if a model fits the situation. In fact the brain doesn’t do a best fit, it does a first fit. Once a model is close enough, the model is applied, even if there’s a better one in the archives.

Overall, the brain does a good job. It looks at a system and matches it with a model of a similar system it experienced in the past. But behind it all the brain is making a dangerous assumption. The brain assumes all systems are static. And that makes for mental models that are static. And because all systems change over time (the only thing we can argue about is the rate of change) the brain’s mental models are always out of date.

Over the years your brain as made a mental model of how your business works – customers do this, competitors do that, and markets do the other. But by definition that mental model is outdated. There needs to be a forcing function that causes us to refute our mental models so we can continually refine them. [A good mantra could be – all mental models are out of fashion until proven otherwise.] But worse than not having a mechanism to refute them, we have a formal business process the demands we converge on our tired mental models year-on-year. And the name of that wicked process – strategic planning.

It goes something like this. Take a little time from your regular job (though you still have to do all that regular work) and figure out how you’re going to grow your business by a large (and arbitrary) percentage. The plan must be achievable (no pie in the sky stuff), it should be tightly defined (even though everyone knows things are dynamic and the plan will change throughout the year), you must do everything you did last year and more and you have fewer resources than last year. Any brain in it’s right will fit the old models to the new normal and put the plan together in the (insufficient) time allotted. The planning process reinforces the re-use of old models.

Because the brain believes everything is static, it’s thinking goes like this – a plan based on anything other than the tried-and-true mental models cannot have certainty or predictability in time or resources. And it’s thinking is right, in part. But because all mental models are out of date, even plans based on existing models don’t have certainty and predictability. And that’s where the wheels fall off.

To inject a bit more reality into strategic planning, ignore the tired old information streams that reinforce existing thinking and find new ones that provide information that contradicts existing mental models. Dig deeply into the mismatch between the new information and the old mental models. What is behind the difference? Is the difference limited to a specific region or product line? Is the mismatch new or has it always been there? The intent of this knee-deep dissection is not to invalidate the old models but to test and refine.

There is infinite detail in the world. Take a look at a tree and there’s a trunk and canopy. Look at the canopy and see the leaves. Look deeper to see a leaf and its veins. In order to effectively handle all this detail our brains create patterns and abstractions to reduce the amount of information needed to make it through the day.

In the case of the tree, the word “tree” is used to capture the whole thing – roots and all. And at a higher level, “tree” can represent almost any type of tree at almost any stage in its life. The abstraction is powerful because it reduces the complexity, as long as everyone’s clear which tree is which.

The message is this. Our brain takes shortcuts with its chunking of the world into mental models that go out style. And our brain uses different levels of abstraction for the same word to mean different things. Care must be taken to overtly question our mental models and overtly question the level of abstraction used when statements of facts are made.

Knowing what isn’t said is almost important as what is said. To maintain this level of clarity requires calm, centered awareness which today’s pace makes difficult.

There’s no pure cure for the syndrome. The best we can do is to be well-rested and aware. And to do that requires professional confidence and personal disciple.

Slowing down just a bit can be faster, and testing the assumptions behind our business models can be even faster. Last year’s mental models and business models should be thought of as guilty until proven relevant. And for that you need to make the time to think.

In today’s world we confuse activity with progress. But really, in today’s dynamic world thinking is progress.

Image credit – eyeliam.

Serious Business

If you’re serious about your work, you’re too serious. We’re all too bound up in this life-or-death, gotta-meet-the-deadline nonsense that does nothing but get in the way.

If you’re serious about your work, you’re too serious. We’re all too bound up in this life-or-death, gotta-meet-the-deadline nonsense that does nothing but get in the way.

If you’re into following recipes, I guess it’s okay to be held accountable to measuring the ingredients accurately and mixing the cake batter with 110% effort. When your business is serious about making more cakes than anyone else on the planet, it’s fine to take that seriously. But if you’re into making recipes, serious doesn’t cut it. Coming up with new recipes demands the freedom of putting together spices that have never been combined. And if you’re too serious, you’ll never try that magical combination that no one else dared.

Serious is far different than fully committed and “all in.” With fully committed, you bring everything you have, but you don’t limit yourself by being too serious. When people are too serious they pucker up and do what they did last time. With “all in” it’s just that – you put all your emotional chips on the line and you tell the dealer to “hit.” If the cards turn in your favor you cash in in a big way. If you bust, you go home, rejuvenate and come back in the morning with that same “all in” vigor you had yesterday and just as many chips. When you’re too serious, you bet one chip at a time. You don’t bet many chips, so you don’t lose many. But you win fewer.

The opposite of serious is not reckless. The opposite of serious is energetic, extravagant, encouraging, flexible, supportive and generous. A culture of accountability is serious. A culture of creativity is not.

I do not advocate behavior that is frivolous. That’s bad business. I do advocate behavior that is daring. That’s good business. Serious connotes measurable and quantifiable, and that’s why big business and best practices like serious. But measurable and quantifiable aren’t things in themselves. If they bring goodness with them, okay. But there’s a strong undercurrent of measurable for measurable’s sake. It’s like we’re not sure what to do, so we measure the heck out of everything. Daring, on the other hand, requires trust is unmeasurable. Never in the history of Six Sigma has there been a project done on daring and never has one of its control strategies relied on trust. That’s because Six Sigma is serious business. Serious connotes stifling, limiting and non-trusting, and that’s just what we don’t need.

Let’s face it, Six Sigma and lean are out of gas. So is tightening-the-screws management. The low hanging fruit has been picked and Human Resources has outed all the mis-fits and malcontents. There’s nothing left to cut and no outliers to eliminate. It’s time to put serious back in its box.

I don’t know what they teach in MBA programs, but I hope it’s trust. And I don’t know if there’s anything we can do with all our all-too-serious managers, but I hope we put them on a program to eliminate their strengths and build on their weaknesses. And I hope we rehire the outliers we fired because they scared all the serious people with their energy, passion and heretical ideas.

When you’re doing the same thing every day, serious has a place. When you’re trying to create the future, it doesn’t. To create the future you’ve got to hire heretics and trust them. Yes, it’s a scary proposition to try to create the future on the backs of rabble-rousers and rebels. But it’s far scarier to try to create it with the leagues of all-too-serious managers that are running your business today.

Image credit — Alan

Solving Intractable Problems

Immediately after there’s an elegant solution to a previously intractable problem, the solution is obvious to others. But, just before the solution those same folks said it was impossible to solve. I don’t know if there’s a name for this phenomenon, but it certainly causes hart burn for those brave enough to take on the toughest problems.

Immediately after there’s an elegant solution to a previously intractable problem, the solution is obvious to others. But, just before the solution those same folks said it was impossible to solve. I don’t know if there’s a name for this phenomenon, but it certainly causes hart burn for those brave enough to take on the toughest problems.

Intractable problems are so fundamental they are no longer seen as problems. Over the years experts simply accept these problems as constraints that must be complied with. Just as the laws of physics can’t be broken, experts behave as if these self-made constraints are iron-clad and believe these self-build walls define the viable design space. To experts, there is only viable design space or bust.

A long time ago these problems were intractable, but now they are not. Today there are new materials, new analysis techniques, new understanding of physics, new measurement systems and new business models.. But, they won’t be solved. When problems go unchallenged and constrain design space they weave themselves into the fabric of how things are done and they disappear. No one will solve them until they are seen for what they are.

It takes time to slow down and look deeply at what’s really going on. But, today’s frantic pace, unnatural fascination with productivity and confusion of activity with progress make it almost impossible to slow down enough to see things as they are. It takes a calm, centered person to spot a fundamental problem masquerading as standard work and best practice. And once seen for what they are it takes a courageous person to call things as they are. It’s a steep emotional battle to convince others their butts have been wet all these years because they’ve been sitting in a mud puddle.

Once they see the mud puddle for what it is, they must then believe it’s actually possible to stand up and walk out of the puddle toward previously non-viable design space where there are dry towels and a change of clothes. But when your butt has always been wet, it’s difficult to imagine having a dry one.

It’s difficult to slow down to see things as they are and it’s difficult to re-map the territory. But it’s important. As continuous improvement reaches the limit of diminishing returns, there are no other options. It’s time to solve the intractable problems.

Image credit – Steven Depolo

Hands-On or Hands-Off?

Hands-on versus hands-off – as a leader it’s a fundamental choice. And for me the single most important guiding principle is – do what it takes to maintain or strengthen the team’s personal ownership of the work.

Hands-on versus hands-off – as a leader it’s a fundamental choice. And for me the single most important guiding principle is – do what it takes to maintain or strengthen the team’s personal ownership of the work.

If things are going well, keep your hands off. This reinforces the team’s ownership and your trust in them. But it’s not hands-off in and ignore them sense; it’s hands-off in a don’t tell them what to do sense. Walk around, touch base and check in to show interest in the work and avoid interrogation-based methods that undermine your confidence in them. This is not to say a hands-off leader only superficially knows what’s going on, it should only look like the leader has a superficial understanding.

The hands-off approach requires a deep understanding of the work and the people doing it. The hands-off leader must make the time to know the GPS coordinates of the project and then do reconnaissance work to identify the positions of the quagmires and quicksand that lay ahead. The hands-off leader waits patiently just in front of the obstacles and makes no course correction if the team can successfully navigate the gauntlet. But when the team is about to sink to their waists, leader gently nudges so they skirt the dangerous territory.

Unless, of course, the team needs some learning. And in that case, the leader lets the team march it’s project into the mud. If they need just a bit of learning the leader lets them get a little muddy; and if the team needs deep learning, the leader lets them sink to their necks. Either way, the leader is waiting under cover as they approach the impending snafu and is right beside them to pull them out. But to the team, the hands-off leader is not out in front scouting the new territory. To them, the hands-off leader doesn’t pay all that much attention. To the team, it’s just a coincidence the leader happens to attend the project meeting at a pivotal time and they don’t even recognize when the leader subtly plants the idea that lets the team pull themselves out of the mud.

If after three or four near-drowning incidents the team does not learn or change it’s behavior, it’s time for the hands-off approach to look and feel more hands-on. The leader calls a special meeting where the team presents the status of the project and grounds the project in the now. Then, with everyone on the same page the leader facilitates a process where the next bit of work is defined in excruciating detail. What is the next learning objective? What is the test plan? What will be measured? How will it be measured? How will the data be presented? If the tests go as planned, what will you know? What won’t you know? How will you use the knowledge to inform the next experiments? When will we get together to review the test results and your go-forward recommendations?

By intent, this tightening down does not go unnoticed. The next bit of work is well defined and everyone is clear how and when the work will be completed and when the team will report back with the results. The leader reverts back to hands-off until the band gets back together to review the results where it’s back to hands-on. It’s the leader’s judgement on how many rounds of hands-on roulette the team needs, but the fun continues until the team’s behavior changes or the project ends in success.

For me, leadership is always hands-on, but it’s hands-on that looks like hands-off. This way the team gets the right guidance and maintains ownership. And as long as things are going well this is a good way to go. But sometimes the team needs to know you are right there in the trenches with them, and then it’s time for hands-on to look like hands-on. Either way, its vital the team knows they own the project.

There are no schools that teach this. The only way to learn is to jump in with both feet and take an active role in the most important projects.

Image credit – Kerri Lee Smith

Out of Context

“It’s a fact.” is a powerful statement. It’s far stronger than a simple description of what happened. It doesn’t stop at describing a sequence of events that occurred in the past, rather it tacks on an implication of what to think about those events. When “it’s a fact” there’s objective evidence to justify one way of thinking over another. No one can deny what happened, no one can deny there’s only one way to see things and no one can deny there’s only one way to think. When it’s a fact, it’s indisputable.

“It’s a fact.” is a powerful statement. It’s far stronger than a simple description of what happened. It doesn’t stop at describing a sequence of events that occurred in the past, rather it tacks on an implication of what to think about those events. When “it’s a fact” there’s objective evidence to justify one way of thinking over another. No one can deny what happened, no one can deny there’s only one way to see things and no one can deny there’s only one way to think. When it’s a fact, it’s indisputable.

Facts aren’t indisputable, they’re contextual. Even when an event happens right in front of two people, they don’t see it the same way. There are actually two events that occurred – one for each viewer. Two viewers, two viewing angles, two contexts, two facts. Right at the birth of the event there are multiple interpretations of what happened. Everyone has their own indisputable fact, and then, as time passes, the indisputables diverge.

On their own there’s no problem with multiple diverging paths of indisputable facts. The problem arises when we use indisputable facts of the past to predict the future. Cause and effect are not transferrable from one context to another, even if based on indisputable facts. The physics of the past (in the true sense of physics) are the same as the physics of today, but the emotional, political, organizational and cultural physics are different. And these differences make for different contexts. When the governing dynamics of the past are assumed to be applicable today, it’s easy to assume the indisputable facts of today are the same as yesterday. Our static view of the world is the underlying problem, and it’s an invisible problem.

We don’t naturally question if the context is different. Mostly, we assume contexts are the same and mostly we’re blind to those assumptions. What if we went the other way and assumed contexts are always different? What would it feel like to live in a culture that always questions the context around the facts? Maybe it would be healthy to justify why the learning from one situation applies to another.

As the pace of change accelerates, it’s more likely today’s context is different and yesterday’s no longer applies. Whether we want to or not, we’ll have to get better at letting go of indisputable facts. Instead of assuming things are the same, it’s time to look for what’s different.

Image credit — Joris Leermakers

Are you striving or thriving?

Thriving is not striving. And they’re more than unrealated. They’re opposites.

Thriving is not striving. And they’re more than unrealated. They’re opposites.

Striving is about the now and what’s in it for me. Thriving is about the greater good and choosing – choosing to choose your own path and choosing to travel it in your own way. Thriving doesn’t thrive because outcomes fit with expectations. Thriving thrives on the journey.

Where striving comes at others’ expense, thriving comes at no one’s expense. Where striving strives on getting ahead, thriving thrives on growing. Striving looks outwardly, thriving looks inwardly. No two words are spelled so similarly yet contradict so vehemently.

Plants thrive when they’re put in the right growing conditions. They grow the way they were meant to grow and they don’t look back. They thrive because they don’t second guess themselves. If they don’t grow as tall as others, they’re happy for the tallest. And if they bloom bigger and brighter than the rest, they’re thoughtful enough to make conversation about other things.

Plants and animals don’t strive. Only people do. Strivers live their lives looking through the lens of the zero sum game. Strivers feel there’s not enough sunlight to go around so they reach and stretch and step on your head so they get a tan and leave you to supplement with vitamin D.

I can deal with strivers that tell you they’re going to step on your head and step on it just as they said. And I have immense disdain for strivers that pretend they’re sunflowers. But when I’m around thrivers I resonate.

Strivers suck energy from the room and thrivers give it way freely. And just as the bumblebee gets joy from spreading the love flower-to-flower, thrivers thrive more as they give more.

If you leave a meeting feeling good about yourself and three days later you rethink things and feel like a lesser person, you were victimized by a striver. If you feel great about yourself after a meeting and three days later feel even better, you rubbed shoulders with a thriver.

Learn to spot the strivers so you can distance yourself. And seek out the thrivers so you can grow with them.

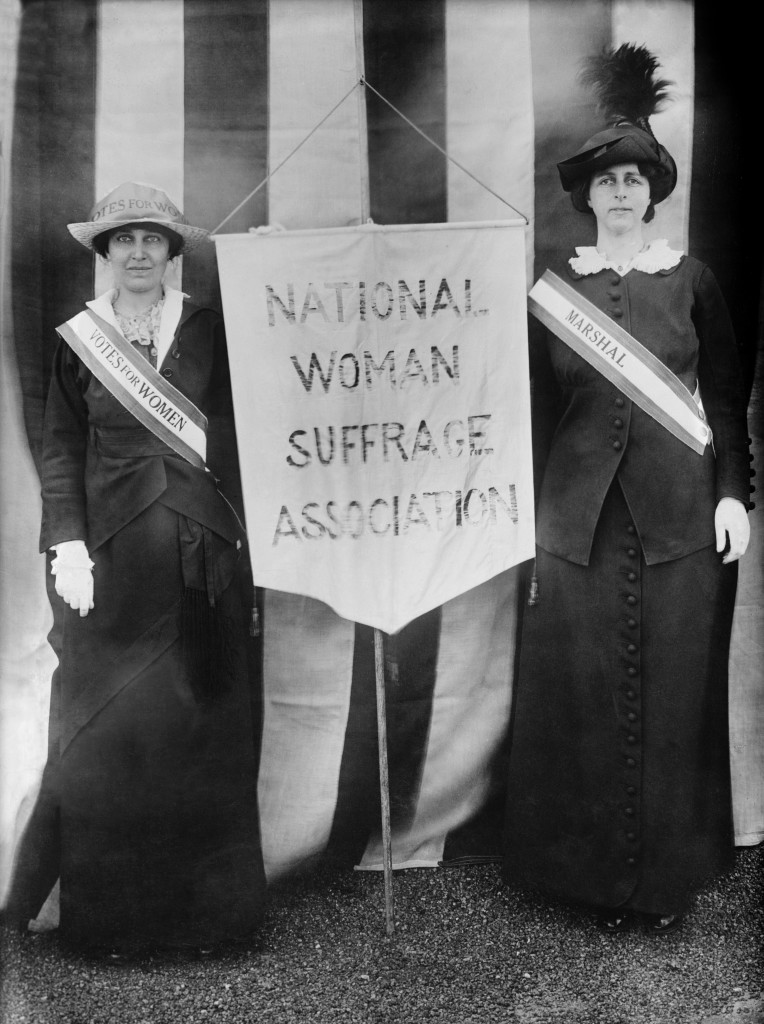

Image credit Brad Smith

If there’s no conflict, there’s no innovation.

With Innovation, things aren’t always what they seem. And the culprit for all this confusion is how she goes about her work. Innovation starts with different, and that’s the source of all the turmoil she creates.

With Innovation, things aren’t always what they seem. And the culprit for all this confusion is how she goes about her work. Innovation starts with different, and that’s the source of all the turmoil she creates.

For the successful company, Innovation demands the company does things that are different from what made it successful. Where the company wants to do more of the same (but done better), Innovation calls it as she sees it and dismisses the behavior as continuous improvement. Innovation is a big fan of continuous improvement, but she’s a bit particular about the difference between doing things that are different and things that are the same.

The clashing of perspectives and the gnashing of teeth is not a bad thing, in fact it’s good. If Innovation simply rolls over when doing the same is rationalized as doing differently, nothing changes and the recipe for success runs out of gas. Said another way, company success is displaced by company failure. When innovation creates conflict over sameness she’s doing the company favor. Though it sometimes gives her a bad name, she’s willing to put up with the attack on her character.

The sacred business model is a mortal enemy of Innovation. Those two have been getting after each other for a long time now, and, thankfully, Innovation is willing to stand tall against the sacred business model. Innovation knows even the most sacred business models have a half-life, and she knows that she must actively dismantle them as everyone else in the company tries to keep them on life support long after they should have passed. Innovation creates things that are different (novel), useful and successful to help the company through the sad process of letting the sacred business model die with dignity. She’s willing to do the difficult work of bringing to life a younger more viral business model, knowing full well she’s creating controversy and turmoil at every turn. Innovation knows the company needs help admitting the business model is tired and old, and she’s willing to do the hard work of putting it out to pasture. She knows there’s a lot of misplaced attachment to the tired business model, but for the sake of the company, she’s willing to put it out of its misery.

For a long time now the company’s products have delivered the same old value in the same old way to the same old customers, and Innovation knows this. And because she knows that’s not sustainable, she makes a stink by creating different and more profitable value to different and more valuable customers. She uses different assumptions, different technologies and different value propositions so the company can see the same old value proposition as just that – old (and tired). Yes, she knows she’s kicking company leaders in the shins when she creates more value than they can imagine, but she’s doing it for the right reasons. Knowing full well people will talk about her behind her back, she’s willing to create the conflict needed to discredit old value proposition and adopt a new one.

Innovation is doing the company a favor when she creates strife, and the should company learn to see that strife not as disagreement and conflict for their own sake, rather as her willingness to do what it takes to help the company survive in an unknown future. Innovation has been around a long time, and she knows the ropes. Over the centuries she’s learned that the same old thing always runs out of steam. And she knows technologies and their business models are evolving faster than ever. Thankfully, she’s willing to do the difficult work of creating new technologies to fuel the future, even as the status quo attacks her character.

Without Innovation’s disruptive personality there would be far less conflict and consternation, but there’d also be far less change, far less growth and far less company longevity. Yes, innovation takes a strong hand and is sometimes too dismissive of what has been successful, but her intentions are good. Yes, her delivery is sometimes too harsh, but she’s trying to make a point and trying to help the company survive.

Keep an eye out for the turmoil and conflict that Innovation creates, and when you see it fan the flames. And when hear the calls of distress of middle managers capsized by her wake of disruption, feel good that Innovation is alive and well doing the hard work to keep the company afloat.

The time to worry is not when Innovation is creating conflict and consternation at every turn; the time to worry is when the telltale signs of her powerful work are missing.

The Top Three Enemies of Innovation – Waiting, Waiting, Waiting

All innovation projects take longer than expected and take more resources than expected. It’s time to change our expectations.

All innovation projects take longer than expected and take more resources than expected. It’s time to change our expectations.

With regard to time and resources, innovation’s biggest enemy is waiting. There. I said it.

There are books and articles that say innovation is too complex to do quickly, but complexity isn’t the culprit. It’s true there’s a lot of uncertainty with innovation, but, uncertainty isn’t the reason it takes as long as it does. Some blame an unhealthy culture for innovation’s long time constant, but that’s not exactly right. Yes, culture matters, but it matters for a very special reason. A culture intolerant of innovation causes a special type of waiting that, once eliminated, lets innovation to spool up to break-neck speeds.

Waiting? Really? Waiting is the secret? Waiting isn’t just the secret, it’s the top three secrets.

In a backward way, our incessant focus on productivity is the root cause for long wait times and, ultimately, the snail’s pace of innovation. Here’s how it goes. Innovation takes a long time so productivity and utilization are vital. (If they’re key for manufacturing productivity they must be key to innovation productivity, right?) Utilization of fixed assets – like prototype fabrication and low volume printed circuit board equipment – is monitored and maximized. The thinking goes – Let’s jam three more projects into the pipeline to get more out of our shared resources. The result is higher utilizations and skyrocketing queue times. It’s like company leaders don’t believe in queuing theory. Like with global warming, the theory is backed by data and you can’t dismiss queuing theory because it’s inconvenient.

One question: If over utilization of shared resources delays each prototype loop by two weeks (creates two weeks of incremental wait time) and you cycle through 10 prototype loops for each innovation project, how many weeks does it delay the innovation project? If you said 20 weeks you’re right, almost. It doesn’t delay just that one project; it delays all the projects that run through the shared resource by 20 weeks. Another question: How much is it worth to speed up all your innovation projects by 20 weeks?

In a second backward way, our incessant drive for productivity blinds us of the negative consequences of waiting. A prototype is created to determine viability of a new technology, and this learning is on the project’s critical path. (When the queue time delays the prototype loop by two weeks, the entire project slips two weeks.) Instead of working to reduce the cycle time of the prototype loop and advance the critical path, our productivity bias makes us work on non-critical path tasks to fill the time. It would be better to stop work altogether and help the company feel the pain of the unnecessarily bloated queue times, but we fill the time with non-critical path work to look busy. The result is activity without progress, and blindness to the reason for the schedule slip – waiting for the over utilized shared resource.

A company culture intolerant of uncertainty causes the third and most destructive flavor of waiting. Where productivity and over utilization reduce the speed of innovation, a culture intolerant of uncertainty stops innovation before it starts. The culture radiates negative energy throughout the labs and blocks all experiments where the results are uncertain. Blocking these experiments blocks the game-changing learning that comes with them, and, in that way, the culture create infinite wait time for the learning needed for innovation. If you don’t start innovation you can never finish. And if you fix this one, you can start.

To reduce wait time, it’s important to treat manufacturing and innovation differently. With manufacturing think efficiency and machine utilization, but with innovation think effectiveness and response time. With manufacturing it’s about following an established recipe in the most productive way; with innovation it’s about creating the new recipe. And that’s a big difference.

If you can learn to see waiting as the enemy of innovation, you can create a sustainable advantage and a sustainable company. It’s time to change expectations around waiting.

Image credit – Pulpolux !!!

Strategic Planning is Dead.

Things are no longer predictable, and it’s time to start behaving that way.

Things are no longer predictable, and it’s time to start behaving that way.

In the olden days (the early 2000s) the pace of change was slow enough that for most the next big thing was the same old thing, just twisted and massaged to look like the next big thing. But that’s not the case today. Today’s pace is exponential, and it’s time to behave that way. The next big thing has yet to be imagined, but with unimaginable computing power, smart phones, sensors on everything and a couple billion new innovators joining the web, it should be available on Alibaba and Amazon a week from next Thursday. And in three weeks, you’ll be able to buy a 3D printer for $199 and go into business making the next big thing out of your garage. Or, you can grasp tightly onto your success and ride it into the ground.

To move things forward, the first thing to do is to blow up the strategic planning process and sweep the pieces into the trash bin of a bygone era. And, the next thing to do is make sure the scythe of continuous improvement is busy cutting waste out of the manufacturing process so it cannot be misapplied to the process of re-imagining the strategic planning process. (Contrary to believe, fundamental problems of ineffectiveness cannot be solved with waste reduction.)

First, the process must be renamed. I’m not sure what to call it, but I am sure it should not have “planning” in the name – the rate of change is too steep for planning. “Strategic adapting” is a better name, but the actual behavior is more akin to probe, sense, respond. The logical question then – what to probe?

[First, for the risk minimization community, probing is not looking back at the problems of the past and mitigating risks that no longer apply.]

Probing is forward looking, and it’s most valuable to probe (purposefully investigate) fertile territory. And the most fertile ground is defined by your success. Here’s why. Though the future cannot be predicted, what can be predicted is your most profitable business will attract the most attention from the billion, or so, new innovators looking to disrupt things. They will probe your business model and take it apart piece-by-piece, so that’s exactly what you must do. You must probe-sense-respond until you obsolete your best work. If that’s uncomfortable, it should be. What should be more uncomfortable is the certainty that your cash cow will be dismantled. If someone will do it, it might as well be you that does it on your own terms.

Over the next year the most important work you can do is to create the new technology that will cause your most profitable business to collapse under its own weight. It doesn’t matter what you call it – strategic planning, strategic adapting, securing the future profitability of the company – what matters is you do it.

Today’s biggest risk is our blindness to the immense risk of keeping things as they are. Everything changes, everything’s impermanent – especially the things that create huge profits. Your most profitable businesses are magnates to the iron filings of disruption. And it’s best to behave that way.

Image credit – woodleywonderworks

Innovation is alive and well.

Innovation isn’t a thing in itself; rather, it’s a result of something. Set the right input conditions, monitor the right things in the right ways, and innovation weaves itself into the genetic makeup of your company. Like ivy, it grabs onto outcroppings that are the heretics and wedges itself into the cracks of the organization. It grows unpredictably, it grows unevenly, it grows slowly. And one day you wake up and your building is covered with the stuff.

Innovation isn’t a thing in itself; rather, it’s a result of something. Set the right input conditions, monitor the right things in the right ways, and innovation weaves itself into the genetic makeup of your company. Like ivy, it grabs onto outcroppings that are the heretics and wedges itself into the cracks of the organization. It grows unpredictably, it grows unevenly, it grows slowly. And one day you wake up and your building is covered with the stuff.

Ivy doesn’t grow by mistake – It takes some initial plantings in strategic locations, some water, some sun, something to attach to, a green thumb and patience. Innovation is the same way.

There’s no way to predict how ivy will grow. One young plant may dominate the others; one trunk may have more spurs and spread broadly; some tangles will twist on each other and spiral off in unforeseen directions; some vines will go nowhere. Though you don’t know exactly how it will turn out, you know it will be beautiful when the ivy works its evolutionary magic. And it’s the same with innovation.

Ivy and innovation are more similar than it seems, and here are some rules that work for both:

- If you don’t plant anything, nothing grows.

- If growing conditions aren’t right, nothing good comes of it.

- Without worthy scaffolding, it will be slow going.

- The best time to plant the seeds was three years ago.

- The second best time to plant is today.

- If you expect predictability and certainty, you’ll be frustrated.

Innovation is the output of a set of biological systems – our people systems – and that’s why it’s helpful to think of innovation as if it’s alive because, well, it is. And like with a thriving colony of ants that grows steadily year-on-year, these living systems work well. From 10,000 foot perspective ants and innovation look the same – lots of chaotic scurrying, carrying and digging. And from an ant-to-ant, innovator-to-innovator perspective they are the same – individuals working as a coordinated collective within a shared mindset of long term sustainability.

Image credit – Cindy Cornett Seigle

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski