Archive for the ‘Seeing Things As They Are’ Category

Finding My Way

I find my way.

I find my way.

I sometimes get caught in other people’s expectations. Aren’t their wants important too?

I can judge myself negatively even when good things happen. Wasn’t greatness possible?

I get angry when my expectations don’t control what the Universe does. Am I alone in this?

But I find my way.

I sometimes prioritize my feelings over others’. Is that good, bad, neither, or both?

I judge myself positively when good things happen. Maybe I had nothing to do with it?

I am happy when I have no expectations. But shouldn’t I expect that?

And I find my way.

I want what I don’t have. Who decides when enough is truly enough?

I get what I want, and then I worry about losing it. But doesn’t everything go away?

I sometimes don’t know what I want. Maybe I don’t want anything but don’t know it?

And I still find my way.

I love helping people. It’s like helping myself twice.

I love my family. I get meaning from them.

I love myself even when some parts of me don’t.

I find my way.

Image credit — Jan Mosimann

Good Teachers Are Better Than Good

Good teachers change your life. They know what you know and bring you along at a pace that’s right for you, not too slowly that you’re bored and not too quickly that your head spins. And everything they do is about you and your learning. Good teachers prioritize your learning above all else.

Good teachers change your life. They know what you know and bring you along at a pace that’s right for you, not too slowly that you’re bored and not too quickly that your head spins. And everything they do is about you and your learning. Good teachers prioritize your learning above all else.

Chris Brown taught me Axiomatic Design. He helped me understand that design is more than what a product does. All meetings and discussions with Chris started with the three spaces – Functional Requirements (FRs) what it does, Design Parameters (DPs) what it looks like, and Process Variables (PVs) how to make it. This was the deepest learning of my professional life. To this day, I am colored by it. And the second thing he taught me was how to recognize functional coupling. If you change one input to the design and two outputs change, that’s functional coupling. You can manage functional coupling if you can see it. But if you can’t see it, you’re hosed. Absolutely hosed.

Vicor Fey taught me TRIZ. He helped me understand the staggering power of words to limit and shape our thinking. I will always remember when he passionately expressed in his wonderful accent, “I hate words!” And to this day, I draw pictures of problems and I avoid words. And the second thing he taught me is that a problem always exists between two things, and those things must touch each other. I make people’s lives miserable by asking – Can you draw me a picture of the problem? And, Which two system elements have the problem, and do they touch each other? And the third thing he taught me was to define problems (Yes, Victor, I know I should say conflicts.) in time. This is amazingly powerful. I ask – “Do you want to solve the problem before it happens, while it happens, or after it happens?” Defining the problem in time is magically informative.

Don Clausing taught me Robust Design. He helped me understand that you can’t pass a robustness test. He said, “If you don’t break it, you don’t know how good it is.” He was an ornery old codger, but he was right. Most tests are stopped before the product fails, and that’s wrong. He also said, “You’ve got to test the old design if you want to know if the new one is better.” To this day, I press for A/B testing, where the old design and new design are tested against the same test protocol. This is much harder than it sounds and much more powerful. He taught me to test designs at stress levels higher than the operating stresses. He said, “Test it, break it, and improve it. And when you run out of time, launch it.” And, lastly, he said, “Improve robustness at the expense of predicting it.” He gave zero value to statistics that predict robustness and 100% value to failure mode-based testing of the old design versus the new one.

The people I work with don’t know Chris, Victor, or Don. But they know the principles I learned from them. I’m a taskmaster when it comes to FRs-DPs-PVs. Designs must work well, be clearly defined by a drawing, and be easy to make. And people know there’s no place in my life for functional coupling. My coworkers know to draw a picture of the problem, and it better be done on one page. And they know the problem must be shown to exist between two things that touch. And they know they’ll get the business from me if they don’t declare that they’re solving it before, during, or after. They know that all new designs must have A/B test results, and the new one must work better than the old one. No exceptions.

I am thankful for my teachers. And I am proud to pass on what they gave me.

Image credit — Christof Timmermann

What makes a strategic plan strategic?

X: We need a strategic plan.

X: We need a strategic plan.

Me: Why do you need one of those?

X: Everybody needs a strategic plan.

Me: Okay. That didn’t work. Let me try it another way. What makes a plan strategic?

X: You start with a strategy and you create a plan to make it happen over the next three years.

Me: So, you plan out the next three years?

X: Yes. Or four.

Me: Doesn’t the plan assume you know how the Universe will behave over the next three years?

X: We know our market, we know our customers, we know our technology, and we make a three-year plan.

Me: And what if something changes, like COVID, tariffs, or a new competitor brings to market something that obsoletes your best product?

X: You can’t plan for that.

Me: Exactly.

X: You’re talking in circles! What do you mean?

Me: If your three-year plan can’t plan for unplanned things, what kind of plan is that?

X: I told you. It’s a strategic plan.

Me: Hmm. Let me try that again. What happens when something unexpected arises and your plan needs to change?

X: It’s a strategic plan. Those don’t change.

Me: Arrg. Do you mean the plan should change, but you don’t make the change? Or strategic plans never change?

X: Strategic plans don’t change because they’re strategic. We put a lot of time into creating them.

Me: They don’t change because they take a lot of time and effort to create?

X: Well, yes. We have long planning meetings, and our best people spend a lot of time creating it.

Me: Do you think the Universe cares how long it took you to create your plan?

X: There you go again with the Universe thing.

Me: What I mean by that is there are many factors outside your control. It’s a big world out there. And you can’t plan for everything.

X: What do you mean? We put everything in the strategic plan.

Me: That’s not the type of everything I’m talking about. I’m talking about things outside your control that you cannot possibly know.

X: Are you saying we don’t know what we’re doing?

Me: No, I’m saying you know everything you’re going to do over the next three years. And that’s the problem.

X: You are frustrating. First you tell me it’s impossible to plan for everything, then you tell me we have a problem because we plan for everything. What’s wrong with you?

Me: That’s the right question. There’s a lot wrong with me. I have a good idea that turns out to be wrong, so I change my plan. I think I understand what’s going on, but I learn that I’m wrong, so I change my plan. I have a plan, but something unexpected happens and turns my plan from good to wrong, so I change it, even if the plan is strategic, whatever that means.

Image credit — Geoff Henson

Change the plan or stay the course?

Plans are good, until they’re not. The key is knowing when to stay the course and when to adjust the plan.

Plans are good, until they’re not. The key is knowing when to stay the course and when to adjust the plan.

The time horizons for strategic plans or corporate initiatives can range from two to five years. To ensure we create the best plans, we assign the work to our best people, we provide them with the best information, and we ask them to use their best judgment. As input, we assess market fundamentals, technology trends, customer segments, our internal talent, our partners, our infrastructure, and our processes. We then set revenue targets and create project plans and resource allocation plans to realize the revenue goals. And then it’s go time.

We initiate the projects, work the plans, and report regularly on the progress. If the progress meets the monthly goal, we keep going. And if the progress doesn’t meet the monthly goal, we keep going. We invested significant time and effort into the plan, and it can be politically difficult, if not bad for your career, to change the plan. It takes confidence and courage to call for a change to a strategic plan or a corporate initiative. But two to five years is a long time, and things can (and do) change over the life of a plan.

A plan is created with the best knowledge available at the time. We assess the environment and use the knowledge to set the financial requirements for the plan. When the environment and requirements change, the plan should change.

Before considering any changes, if we learn that the assumptions used to create the plan are invalid, the plan should change. For example, if the resource allocation is insufficient, the timelines should be extended, resources should be added, or the scope of the work should be reduced. I think changing the plan is responsible management, and I think it’s irresponsible management to stay the course.

The environment can change in many ways. Here are five categories of change: tariffs, competition, internal talent (key people move on), new customer learning, and new technical learning (e.g., more technical risk than anticipated). Significant changes in any of these categories should trigger an assessment of the plan’s viability. This is not a sign of weakness. This is responsible management. And if the change in the environment invalidates the plan’s assumptions, the plan should change.

The specification (revenue targets) for the plans can change. There are at least two flavors of change: an increase in revenue goals or a shorter timeline to achieve revenue goals, which are usually caused by changes to the environment. And when there’s a need for more revenue or to deliver it sooner, the plans should be assessed and changed. Again, I think this is good management practice and not a sign of failure or weakness. When we realize the plan won’t meet the new specification, we should modify the plan.

When we learn the assumptions are wrong, we should change the plan. When the environment changes, we should change the plan. And when the specification changes, we should change the plan.

Image credit — Charlie Day

Two Tricks to Improve Understanding of New Ideas

When you want someone to understand your new idea, draw a picture for yourself. Set the constraint that you cannot use words on the page. Shapes, arrows, cartoons – yes. Words – no. Once you’re convinced your one-pager captures your idea, set another constraint. When you show your picture to someone, you cannot speak. Your one-page picture must stand on its own. I think you’ll find that this second constraint will cause you to improve your image, which will help others (and you) better understand your idea. You can use your words when you explain your one-pager to your target audience, which will improve clarity and understanding.

When you want someone to understand your new idea, draw a picture for yourself. Set the constraint that you cannot use words on the page. Shapes, arrows, cartoons – yes. Words – no. Once you’re convinced your one-pager captures your idea, set another constraint. When you show your picture to someone, you cannot speak. Your one-page picture must stand on its own. I think you’ll find that this second constraint will cause you to improve your image, which will help others (and you) better understand your idea. You can use your words when you explain your one-pager to your target audience, which will improve clarity and understanding.

When you want someone to understand that your new idea is possible, build a prototype and do a demo. Use your one-pager to create a storyboard of the demo. The storyboard can be a series of cartoons that describe what will happen during the demo. And like with the one-pager, your storyboard cannot use words. And once you think your storyboard communicates your idea, set the constraint that you cannot speak during the demo, and try to improve the storyboard to support a no-word demo. You can use your words during the demo to further improve clarity and understanding.

Make no mistake, the one-pager and the storyboard are for you. They will help you better understand your idea so you can help people understand it better.

Image credit – Jennifer Moo

What’s not on the agenda?

To be more effective at a meeting, take the time to dissect the meeting agenda and details.

To be more effective at a meeting, take the time to dissect the meeting agenda and details.

Who called the meeting? If the CEO calls the meeting, you know your role. And you know your role if a team member calls the meeting. Knowledge of the organizer helps you understand your role in the meeting.

Who is invited to the meeting? If you are the only one invited, it’s a one-on-one meeting. You know there will be dialogue and back-and-forth discussion. If there are fifty people invited, you know it will be a listening meeting. And if all the company leaders are invited, maybe you should dress up a bit.

What is the sequence of the invitees? Who is first on the invite list?

Who is not invited to the meeting? This says a lot, but takes a little thought to figure out what it says.

How long is the meeting? A fifteen-minute daily standup meeting is informal but usually requires a detailed update on yesterday’s progress. An all-day meeting means you’ve got to pace yourself and bring your coffee.

Is lunch served? The better the lunch, the more important the meeting. And it’s the same for snacks.

Is the meeting in-person or remote? In-person meetings are more important and more impactful.

If pre-read material is sent out two days before the meeting, the organizer is on their game. If the pre-read material is sent out three minutes before the meeting, it’s a different story.

If there’s no agenda, it means the organizer isn’t all that organized. Skip these meetings if you can. But if you can’t, bring your laptop and be ready to present your best stuff. If no one asks you to talk, keep quiet and listen. If you’re asked to present, present something if you can. And if you can’t, say you’re not ready because the topic was not included in the agenda.

The best agendas define the topics, the leader of each topic, and the time blocks.

All these details paint a picture of the upcoming meeting and help you know what to expect. When you know what to expect will enable you to hear the things that aren’t said and the discussions that don’t happen.

When the group avoids talking about the charged topic or the uncomfortable situation, you’ll recognize it. And because you know who called the meeting, the attendees, and the meeting context, you’ll help the group discuss what needs to be discussed. You’ll know when to ask a seemingly innocent question to help the group migrate to the right discussion. And you’ll know when it’s okay to put your hand up and tell the group they’re avoiding an important topic that should be discussed.

Anyone can follow the agenda, but it takes preparation, insight, awareness, and courage to help the group address the important but uncomfortable things not on the agenda.

Image credit — Joachim Dobler

Making a difference starts with recognizing the opportunity to make one.

It doesn’t take much to make a difference, but if you don’t recognize the need to make one, you won’t make one.

It doesn’t take much to make a difference, but if you don’t recognize the need to make one, you won’t make one.

When you’re in a meeting, watch and listen. If someone is quiet, ask them a question. My favorite is “What do you think?” Your question says you value them and their thinking, and that makes a difference. Others will recognize the difference you made, and that may inspire them to make a similar difference at their next meeting.

When you see a friend in the hallway, look them in the eyes, smile, and ask them what they’re up to. Listen to their words but more importantly watch their body language. If you recognize they are energetic, acknowledge their energy, ask what’s fueling them, and listen. Ask more questions to let them know you care. That will make a difference. If you recognize they have low energy, tell them, and then ask what that’s all about. Try to understand what’s going on for them. You don’t have to fix anything to make a difference, you have to invest in the conversation. They’ll recognize your genuine interest and that will make a difference.

If you remember someone is going through something, send them a simple text – “I’m thinking of you.” That’s it. Just say that. They’ll know you remembered their situation and that you care. And that will make a difference. Again, you don’t have to fix anything. You just have to send the text.

Check in with a friend. That will make a difference.

When you learn someone got a promotion, send them a quick note. Sooner is better, but either way, you’ll make a difference.

Ask someone if they need help. Even if they say no, you’ve made a difference. And if they say yes, help them. That will make a big difference.

And here’s a little different spin. If you need help, ask for it. Tell them why you need it and explain why you asked them. You’ll demonstrate vulnerability and they’ll recognize you trust them. Difference made. And your request for help will signal that you think they’re capable and caring. Another difference made.

It doesn’t take much to make a difference. Pay attention and take action and you’ll make a difference. But really, you’ll make two differences. You’ll make a difference for them and you’ll make a difference for yourself.

Image credit — Geoff Henson

It’s time for the art of the possible.

Tariffs. Economic uncertainty. Geopolitical turmoil. There’s no time for elegance. It’s time for the art of the possible.

Tariffs. Economic uncertainty. Geopolitical turmoil. There’s no time for elegance. It’s time for the art of the possible.

Give your sales team a reason to talk to customers. Create something that your salespeople can talk about with customers. A mildly modified product offering, a new bundling of existing products, a brochure for an upcoming new product, a price reduction, a program to keep prices as they are even though tariffs are hitting you. Give them a chance to talk about something new so the customers can buy something (old or new).

Think Least Launchable Unit (LLU). Instead of a platform launch that can take years to develop and commercialize, go the other way. What’s the minimum novelty you can launch? What will take the least work to launch the smallest chunk of new value? Whatever that is, launch it now.

Take a Frankensteinian approach. Frankenstein’s monster was a mix and match of what the good doctor had scattered about his lab. The head was too big, but it was the head he had. And he stitched onto the neck most crudely with the tools he had at his disposal. The head was too big, but no one could argue that the monster didn’t have a head. And, yes, the stitching was ugly, but the head remained firmly attached to the neck. Not many were fans of the monster, but everyone knew he was novel. And he was certainly something a sales team could talk about with customers. How can you combine the head from product A with the body of product B? How can you quickly stitch them together and sell your new monster?

Less-With-Far-Less. You’ve already exhausted the more-with-more design space. And there’s no time for the technical work to add more. It’s time for less. Pull out some functionality and lots of cost. Make your machines do less and reduce the price. Simplify your offering and make things easier for your customers. Removing, eliminating, and simplifying usually comes with little technical risk. Turning things down is far easier than turning them up. You’ll be pleasantly surprised how excited your customers will be when you offer them slightly less functionality for far less money.

These are trying times, but they’re not to be wasted. The pressure we’re all under can open us up to do new work in new ways. Push the envelope. Propose new offerings that are inelegant but take advantage of the new sense of urgency forced.

Be bold and be fast.

Image credit — Geoff Henson

What Is and Is Not

Building trust takes time. Tearing it apart does not.

Building trust takes time. Tearing it apart does not.

Seeing what is there is easy. Seeing what is missing is not.

Concentrating is easy for some. For others, daydreaming is not.

Bringing your whole self to work takes courage. Pretending does not.

Hearing is easy. Listening is not.

Trying is subjective. Doing is not.

Telling the truth is appreciated. Done unskillfully, it is not.

Singing is easy for some. For others, not singing is not.

Going fast can be good. Going too fast cannot.

Hearing what is said is easy. Hearing what is withheld is not.

Finishing takes a long time. Quitting should not.

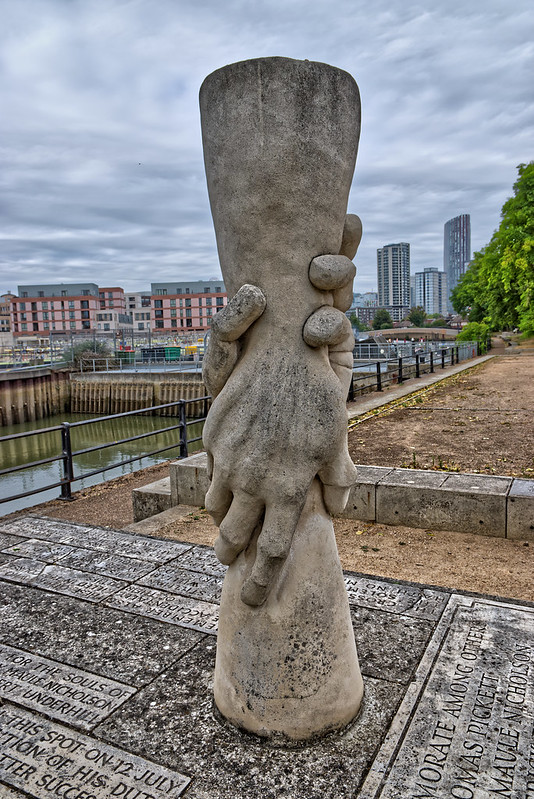

Image credit — Mike Keeling

Bringing Your Whole Self To The Party

If it’s taken from you, you’ll have a problem if you think it was yours.

If it’s taken from you, you’ll have a problem if you think it was yours.

When it’s taken from you, it doesn’t matter if it was never yours.

No one can take anything from you unless you think it is yours.

There can be no loss if it was never yours to have.

You can be manipulated if they know you have a problem letting go.

Said differently, if you can let go you can’t be manipulated.

Whether you want to admit it or not, it all goes away.

But if you see your favorite mug as already broken, there’s no problem when it breaks.

If you recognize your thirties will end, you won’t feel slighted when you start your fourth decade.

And it’s the same when you start your your fifth.

When you know things will end, their ending comes easier.

When you’re aware it will end, you can do it your way.

When you’re aware it’s finite, it’s easier to do what you think is right.

When you’re it all goes away, you can better appreciate what you have.

When you’re aware everything has a half-life, you’re less likely to live your life as a half-person.

Wouldn’t you like to do things your way?

Wouldn’t you like to do what you think is right?

Wouldn’t you like to live as a whole person?

Wouldn’t you like to appreciate what you have?

Would’t you like to bring your whole self to the party?

If so, why not embrace the impermanence?

Image credit — 正面顔〜〜〜(- .. -)

Improvement In Reverse Sequence

Before you can make improvements, you must identify improvement opportunities.

Before you can make improvements, you must identify improvement opportunities.

Before you can identify improvement opportunities, you must look for them.

Before you can look for improvement opportunities, you must believe improvement is possible.

Before believing improvement is possible, you must admit there’s a need for improvement.

Before you can admit the need for improvement, you must recognize the need for improvement.

Before you can recognize the need for improvement, you must feel dissatisfied with how things are.

Before you can feel dissatisfied with how things are, you must compare how things are for you relative to how things are for others (e.g., competitors, coworkers).

Before you can compare things for yourself relative to others, you must be aware of how things are for others and how they are for you.

Before you can be aware of how things are, you must be calm, curious, and mindful.

Before you can be calm, curious, and mindful, you must be well-rested and well-fed. And you must feel safe.

What choices do you make to be well-rested? How do you feel about that?

What choices do you make to be well-fed? How do you feel about that?

What choices do you make to feel safe? How do you feel about that?

Image credit — Philip McErlean

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski