Archive for the ‘Seeing Things As They Are’ Category

The Chief Do-the-Right-Thing Officer – a new role to protect your brand.

Our unhealthy fascination with ever-increasing shareholder value has officially gone too far. In some companies dishonesty is now more culturally acceptable than missing the numbers. (Unless, of course, you get caught. Then, it’s time for apologies.) The sacrosanct mission statement can’t save us. Even the most noble can be stomped dead by the dirty boots of profitability.

Our unhealthy fascination with ever-increasing shareholder value has officially gone too far. In some companies dishonesty is now more culturally acceptable than missing the numbers. (Unless, of course, you get caught. Then, it’s time for apologies.) The sacrosanct mission statement can’t save us. Even the most noble can be stomped dead by the dirty boots of profitability.

Though, legally, companies can self-regulate, practically, they cannot. There’s nothing to balance the one-sided, hedonistic pursuit of profitability. What’s needed is a counterbalancing mechanism of equal and opposite force. What’s needed is a new role that is missing from today’s org chart and does not have a name.

Ombudsman isn’t the right word, but part of it is right – the part that investigates. But the tense is wrong – the ombudsman has after-the-fact responsibility. The ombudsman gets to work after the bad deed is done. And another weakness – ombudsman don’t have equal-and-opposite power of the C-suite profitability monsters. But most important, and what can be built on, is the independent nature of the ombudsman.

Maybe it’s a proactive ombudsman with authority on par with the Board of Directors. And maybe their independence should be similar to a Supreme Court justice. But that’s not enough. This role requires hulk-like strength to smash through the organizational obfuscation fueled by incentive compensation and x-ray vision to see through the magical cloaking power of financial shenanigans. But there’s more. The role requires a deep understanding of complex adaptive systems (people systems), technology, patents and regulatory compliance; the nose of an experienced bloodhound to sniff out the foul; and the jaws of a pit bull that clamp down and don’t let go.

Ombudsman is more wrong than right. I think liability is better. Liability, as a word, has teeth. It sounds like it could jeopardize profitability, which gives it importance. And everyone knows liability is supposed to be avoided, so they’d expect the work to be proactive. And since liability can mean just about anything, it could provide the much needed latitude to follow the scent wherever it takes. Chief Liability Officer (CLO) has a nice ring to it.

[The Chief Do-The-Right-Thing Officer is probably the best name, but its acronym is too long.]

But the Chief Liability Officer (CLO) must be different than the Chief Innovation Officer (CIO), who has all the responsibility to do innovation with none of the authority to get it done. The CLO must have a gavel as loud as the Chief Justice’s, but the CLO does not wear the glasses of a lawyer. The CLO wears the saffron robes of morality and ethics.

Is Chief Liability Officer the right name? I don’t know. Does the CLO report to the CEO or the Board of Directors? Don’t know. How does the CLO become a natural part of how we do business? I don’t know that either.

But what I do know, it’s time to have those discussions.

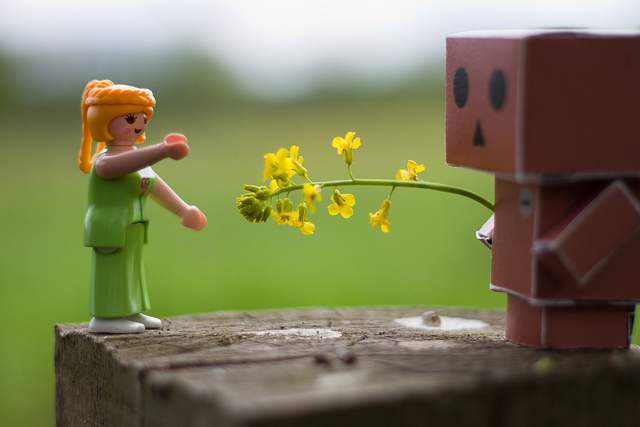

Image credit – Dietmar Temps

Geometric Success Through Mentorship

Business processes and operating plans don’t get things done. People do. And the true blocker of progress is not bureaucracy; it’s the lack of clarity of people. And that’s why mentorship is so important.

Business processes and operating plans don’t get things done. People do. And the true blocker of progress is not bureaucracy; it’s the lack of clarity of people. And that’s why mentorship is so important.

My definition of mentorship is: work that provides knowledge, support and advocacy necessary for new people to get things done. New can be new to company, new to role, or new to new environments or circumstances.

Mentorship is about helping new people recognize and understand unwritten rules on how things are done; helping them see the invisible power dynamics that generate the invisible forcing function that makes things happen; and supporting them as they navigate the organizational riptide.

The first job of a mentor is to commit to spending time with a worthy mentee. Check-the-box mentorship (mentorship for compliance) does not take a lot of time. (Usually several meetings will do.) But mentorship done well, mentorship worthy of the mentee, takes time and emotional investment.

Mentorship starts with a single page definition of the projects the mentee must get done. It’s a simple spreadsheet where each project has its own row with multiple columns for the projects that define: what must get done by the end of the year, and how to know it was done; the major milestones (and dates) along the way; what was done last month; what will be done this month. After all the projects are listed in order of importance, the number of projects is reduced from 10-20 down to 3-4. The idea is to list on the front of the page only the projects that can be accomplished by a mere mortal. The remaining 16-17 are moved to the back, never to be discussed again. (It’s still one page if you use the back.)

[Note: The mentee’s leader will be happy you helped reduce the workload down to a reasonable set of projects. They knew there were too many projects, but their boss wanted them to sign up for too much to ensure there was no chance of success and no time to think.]

Once the year-end definition of success is formalized for each project, this month’s tasks are defined. Using your knowledge of organizational dynamics and how things actually get done, you tell them what to do and how to do it. For the next four weekly meetings you ask them what they and help them get the tasks done. You don’t do the tasks for them, you tell them how to do it and how to work with. Over the next months, telling morphs to suggesting.

The learning comes when your suggested approach differs from their logical, straightforward approach. You explain the history, explain the official process is outdated and no one does it that way, suggest they talk to the little-known subject matter expert who has done similar work and introduce them to the deep-in-the-org-chart stalwart who can allocate resources to support the work.

Week-by-week and month-by-month, the project work gets done and the mentee learns how to get it done. The process continues for at least one year. If you are not willing to meet 40-50 times over the course of a year, you aren’t serious about mentorship. Think that’s too much? It isn’t. That’s what it takes. Still think that’s too much? If you meet for 30 minutes a week, that’s only 20-25 hours per year. At the end of a year, 3-4 projects will be completed successfully and a new person will know how to do 3-4 more next year, and the year after that. Then, because they know the value of mentorship, they become a mentor and help a new person get 3-4 projects done. That’s a lot of projects. Done right, success through mentorship is geometric.

Companies are successful when they complete their projects. And the knowledge needed to complete the projects is not captured in the flowcharts of the official business processes – it’s captured in the hearts and minds of the people.

New people don’t know how things get done, but they need to. And mentorship is the best way to teach them. It’s impossible to calculate the return on investment (ROI) for mentorship. You either believe in mentorship or you don’t. And I believe in it.

My mentorship work is my most meaningful work, and it has little to do with the remarkable business results. The personal relationships I have developed through my mentorship work are some of the most rewarding of my life.

I urge you, for your own well-being, to give mentorship a try.

Image credit — Bryan Jones

Recalibrating Your Fear

Everyone is looking for that new thing, that differentiator, that edge. The important filtering question is: Has it been done before? If it has been done before it cannot be a new thing (that’s a rule), so it’s important to limit yourself to things that have not been done. Sounds silly to say, but with today’s hectic pace sometimes that distinction is overlooked.

Everyone is looking for that new thing, that differentiator, that edge. The important filtering question is: Has it been done before? If it has been done before it cannot be a new thing (that’s a rule), so it’s important to limit yourself to things that have not been done. Sounds silly to say, but with today’s hectic pace sometimes that distinction is overlooked.

Once your eyeballs are calibrated, it pretty easy to see the vital yet-to-be-done work. But calibration is definitely needed because things don’t look as they seem. Here are a few examples to help you calibrate.

“It can’t be done.” This really means is it was tried some time ago by someone who doesn’t work here anymore and we’ve forgotten why, but the one experiment that was run did not work. This a good indication of fertile ground. Someone a long time ago thought it was important enough to try and it still has not been done successfully. And, new materials and manufacturing processes have been created and opened up new design space. Give it a try.

“That will never work.” See above.

“You can’t do that.” This means you (and, likely your industry) have a policy that has blocks this new idea. It may not be the best idea, but since policy prohibits it, you have the design space all to yourself if you want it. (That is, of course, if you want to compete with no one.) Likely there are no physical constraints, just the emotional constraints you created with your policy. It’s all yours, if you try it.

“No one will buy that.” This means no one offers a product like that. It means your industry doesn’t understand it because you or your competitors don’t sell anything like it. Though Marketing knows the inherent uncertainty, they don’t know the market potential. But you know you’re onto something. Try it.

“That’s just a niche market.” This means there’s a market that’s buying your product even though you’ve spent no time or energy to develop that market. It’s an accidental market. It’s small because it’s young and because you (and your competition) haven’t invested in it nor have developed an unique new product for it. The growth is all yours if you try.

Organizations create blocking mechanisms and tricky language to protect themselves from the new-and-different because the new-and-different are scary. But organizations desperately need new-and-different. And for that they desperately need to do things that haven’t been done.

The first step is to recognize the fertile design space and untilled markets your fear has created for you.

Image credit — Jordan Oram

Skillful and Unskillful

I used to believe others were responsible for my problem, now I believe I am responsible. The turning point came when I was struggling with a stressful situation a friend gave me some simple advice. He said “Look inside.” For some reason, that was enough for me to start my transformation.

I used to believe others were responsible for my problem, now I believe I am responsible. The turning point came when I was struggling with a stressful situation a friend gave me some simple advice. He said “Look inside.” For some reason, that was enough for me to start my transformation.

I used to compare myself to others. It caused me great pain because I judged myself as inferior. Over time I learned that others compared themselves to me and felt the same way. Also, I learned that success brings problems of its own, namely worry and anxiety around losing what “success” has brought. Though I still sometimes feel inferior, I’ve learned to recognize the symptoms, and once I call them by name, I can move forward.

I used to care too much about money. Though I still care about money, I care more about time.

I used to wrestle with the past and worry about the future. Now I sit in the present, and I like it better. I still slip sometimes, but I catch myself pretty quickly.

I used to be largely unaware of my lack of awareness. Now that I’ve learned to be more aware of it, I’m closer to the people I care about. And I’m aware that I’m just getting started.

I used to want more of everything. Now I have enough and I want to enjoy it.

I used to want to climb the corporate ladder, now I want to do amazing work.

I used to judge my younger self though my older self’s eyes. That was unskillful. I’ve realized that as a younger person my intensions were good, just as they are today. And, I’ve learned that perfection is an unattainable goal and that sometimes I forget.

I used to think that I had to do everything myself. Now I get great joy from helping others do things they thought they couldn’t.

I used to think of myself as a steamroller and I was proud of it. Now I’m a behind-the-scenes conductor who is far more effective and much happier.

I used to be afraid to share my inner thoughts and feelings, but I’m getting better at that.

Image credit – Jai Kapoor

There is no control. There is only trust.

Control strategies don’t work, but trust strategies do.

Control strategies don’t work, but trust strategies do.

Nothing goes as planned. Trying to control things tightly is wasteful. It takes too much energy to batten down all the hatches and keep them that way every-day-all-day. Maybe no water gets in, but the crew doesn’t get enough oxygen and their brains wither.

Trust on the other hand, is flexible and far more efficient. It takes little energy to hire a pro, give them the right task and get out of the way. And with the best pros it requires even less energy because the three-step becomes a two-step – hire them and get out of the way.

When both hands are continuously busy pulling the levers of contingency plans there are no hands left to point toward the future. When both arms are clinging onto the artificial schedule of the project plan there are no arms left to conduct the orchestra. Control strategies make sure even the piccolo plays the right notes at the right time, while trust strategies let the violins adjust based on their ear and intuition and even let the conductors write their own sheet music.

Control is an illusion, but trust is real. The best statistical analyses are rearward-looking and provide no control in a changing environment. (You can’t drive a car by looking in the rear view mirror.) Yet, that’s the state-of-the-art for control strategies – don’t change the inputs, don’t change the process and we’ll get what we got last time. That’s not control. That’s self-limiting.

Trust is real because people and their relationships are real. Trust is a contract between people where one side expects hard work and good judgment and the other side expects to be challenged and to be given the flexibility to do the work as they see fit. Trust-based systems are far more adaptable than if-then control strategies. No control algorithm can effectively handle unanticipated changes in input conditions or unplanned drift in decision criteria, but people and their judgement can. In fact, that’s what people are good at, and they enjoy doing it. And that’s a great recipe for an engaged work force.

Control strategies are popular because they help us believe we have control. And they’re ineffective for the same reason. Trust strategies are not popular because they acknowledge we have no real control and rely on judgment. And that’s why they’re effective.

When control strategies fail, trust strategies are implemented to save the day. When the wheels fall off a project, the best pro in the company is brought in to fix what’s broken. And the best pro is the most trusted pro. And their charge – Tell us what’s wrong (Use your judgement.), tell us how you’re going to fix it (Use your best judgement for that.) and tell us what you need to fix it. (And use your best judgement for that, too.)

In the end, trust trumps control. But only after all other possibilities are exhausted.

Image credit – Dobi.

All Your Mental Models are Obsolete

Even after playing lots of tricks to reduce its energy consumption, our brains still consume a large portion of the calories we eat. Like today’s smartphones it’s computing power is too big for it’s battery so its algorithms conserve every chance they get. One of its go-to conservation strategies is to make mental models. The models capture the essence of a system’s behavior without the overhead of retaining all the details of the system.

And as the brain goes about its day it tries to fit what it sees to its portfolio of mental models. Because mental models are so efficient, to save juice the brain is pretty loose with how it decides if a model fits the situation. In fact the brain doesn’t do a best fit, it does a first fit. Once a model is close enough, the model is applied, even if there’s a better one in the archives.

Overall, the brain does a good job. It looks at a system and matches it with a model of a similar system it experienced in the past. But behind it all the brain is making a dangerous assumption. The brain assumes all systems are static. And that makes for mental models that are static. And because all systems change over time (the only thing we can argue about is the rate of change) the brain’s mental models are always out of date.

Over the years your brain as made a mental model of how your business works – customers do this, competitors do that, and markets do the other. But by definition that mental model is outdated. There needs to be a forcing function that causes us to refute our mental models so we can continually refine them. [A good mantra could be – all mental models are out of fashion until proven otherwise.] But worse than not having a mechanism to refute them, we have a formal business process the demands we converge on our tired mental models year-on-year. And the name of that wicked process – strategic planning.

It goes something like this. Take a little time from your regular job (though you still have to do all that regular work) and figure out how you’re going to grow your business by a large (and arbitrary) percentage. The plan must be achievable (no pie in the sky stuff), it should be tightly defined (even though everyone knows things are dynamic and the plan will change throughout the year), you must do everything you did last year and more and you have fewer resources than last year. Any brain in it’s right will fit the old models to the new normal and put the plan together in the (insufficient) time allotted. The planning process reinforces the re-use of old models.

Because the brain believes everything is static, it’s thinking goes like this – a plan based on anything other than the tried-and-true mental models cannot have certainty or predictability in time or resources. And it’s thinking is right, in part. But because all mental models are out of date, even plans based on existing models don’t have certainty and predictability. And that’s where the wheels fall off.

To inject a bit more reality into strategic planning, ignore the tired old information streams that reinforce existing thinking and find new ones that provide information that contradicts existing mental models. Dig deeply into the mismatch between the new information and the old mental models. What is behind the difference? Is the difference limited to a specific region or product line? Is the mismatch new or has it always been there? The intent of this knee-deep dissection is not to invalidate the old models but to test and refine.

There is infinite detail in the world. Take a look at a tree and there’s a trunk and canopy. Look at the canopy and see the leaves. Look deeper to see a leaf and its veins. In order to effectively handle all this detail our brains create patterns and abstractions to reduce the amount of information needed to make it through the day.

In the case of the tree, the word “tree” is used to capture the whole thing – roots and all. And at a higher level, “tree” can represent almost any type of tree at almost any stage in its life. The abstraction is powerful because it reduces the complexity, as long as everyone’s clear which tree is which.

The message is this. Our brain takes shortcuts with its chunking of the world into mental models that go out style. And our brain uses different levels of abstraction for the same word to mean different things. Care must be taken to overtly question our mental models and overtly question the level of abstraction used when statements of facts are made.

Knowing what isn’t said is almost important as what is said. To maintain this level of clarity requires calm, centered awareness which today’s pace makes difficult.

There’s no pure cure for the syndrome. The best we can do is to be well-rested and aware. And to do that requires professional confidence and personal disciple.

Slowing down just a bit can be faster, and testing the assumptions behind our business models can be even faster. Last year’s mental models and business models should be thought of as guilty until proven relevant. And for that you need to make the time to think.

In today’s world we confuse activity with progress. But really, in today’s dynamic world thinking is progress.

Image credit – eyeliam.

Serious Business

If you’re serious about your work, you’re too serious. We’re all too bound up in this life-or-death, gotta-meet-the-deadline nonsense that does nothing but get in the way.

If you’re serious about your work, you’re too serious. We’re all too bound up in this life-or-death, gotta-meet-the-deadline nonsense that does nothing but get in the way.

If you’re into following recipes, I guess it’s okay to be held accountable to measuring the ingredients accurately and mixing the cake batter with 110% effort. When your business is serious about making more cakes than anyone else on the planet, it’s fine to take that seriously. But if you’re into making recipes, serious doesn’t cut it. Coming up with new recipes demands the freedom of putting together spices that have never been combined. And if you’re too serious, you’ll never try that magical combination that no one else dared.

Serious is far different than fully committed and “all in.” With fully committed, you bring everything you have, but you don’t limit yourself by being too serious. When people are too serious they pucker up and do what they did last time. With “all in” it’s just that – you put all your emotional chips on the line and you tell the dealer to “hit.” If the cards turn in your favor you cash in in a big way. If you bust, you go home, rejuvenate and come back in the morning with that same “all in” vigor you had yesterday and just as many chips. When you’re too serious, you bet one chip at a time. You don’t bet many chips, so you don’t lose many. But you win fewer.

The opposite of serious is not reckless. The opposite of serious is energetic, extravagant, encouraging, flexible, supportive and generous. A culture of accountability is serious. A culture of creativity is not.

I do not advocate behavior that is frivolous. That’s bad business. I do advocate behavior that is daring. That’s good business. Serious connotes measurable and quantifiable, and that’s why big business and best practices like serious. But measurable and quantifiable aren’t things in themselves. If they bring goodness with them, okay. But there’s a strong undercurrent of measurable for measurable’s sake. It’s like we’re not sure what to do, so we measure the heck out of everything. Daring, on the other hand, requires trust is unmeasurable. Never in the history of Six Sigma has there been a project done on daring and never has one of its control strategies relied on trust. That’s because Six Sigma is serious business. Serious connotes stifling, limiting and non-trusting, and that’s just what we don’t need.

Let’s face it, Six Sigma and lean are out of gas. So is tightening-the-screws management. The low hanging fruit has been picked and Human Resources has outed all the mis-fits and malcontents. There’s nothing left to cut and no outliers to eliminate. It’s time to put serious back in its box.

I don’t know what they teach in MBA programs, but I hope it’s trust. And I don’t know if there’s anything we can do with all our all-too-serious managers, but I hope we put them on a program to eliminate their strengths and build on their weaknesses. And I hope we rehire the outliers we fired because they scared all the serious people with their energy, passion and heretical ideas.

When you’re doing the same thing every day, serious has a place. When you’re trying to create the future, it doesn’t. To create the future you’ve got to hire heretics and trust them. Yes, it’s a scary proposition to try to create the future on the backs of rabble-rousers and rebels. But it’s far scarier to try to create it with the leagues of all-too-serious managers that are running your business today.

Image credit — Alan

Solving Intractable Problems

Immediately after there’s an elegant solution to a previously intractable problem, the solution is obvious to others. But, just before the solution those same folks said it was impossible to solve. I don’t know if there’s a name for this phenomenon, but it certainly causes hart burn for those brave enough to take on the toughest problems.

Immediately after there’s an elegant solution to a previously intractable problem, the solution is obvious to others. But, just before the solution those same folks said it was impossible to solve. I don’t know if there’s a name for this phenomenon, but it certainly causes hart burn for those brave enough to take on the toughest problems.

Intractable problems are so fundamental they are no longer seen as problems. Over the years experts simply accept these problems as constraints that must be complied with. Just as the laws of physics can’t be broken, experts behave as if these self-made constraints are iron-clad and believe these self-build walls define the viable design space. To experts, there is only viable design space or bust.

A long time ago these problems were intractable, but now they are not. Today there are new materials, new analysis techniques, new understanding of physics, new measurement systems and new business models.. But, they won’t be solved. When problems go unchallenged and constrain design space they weave themselves into the fabric of how things are done and they disappear. No one will solve them until they are seen for what they are.

It takes time to slow down and look deeply at what’s really going on. But, today’s frantic pace, unnatural fascination with productivity and confusion of activity with progress make it almost impossible to slow down enough to see things as they are. It takes a calm, centered person to spot a fundamental problem masquerading as standard work and best practice. And once seen for what they are it takes a courageous person to call things as they are. It’s a steep emotional battle to convince others their butts have been wet all these years because they’ve been sitting in a mud puddle.

Once they see the mud puddle for what it is, they must then believe it’s actually possible to stand up and walk out of the puddle toward previously non-viable design space where there are dry towels and a change of clothes. But when your butt has always been wet, it’s difficult to imagine having a dry one.

It’s difficult to slow down to see things as they are and it’s difficult to re-map the territory. But it’s important. As continuous improvement reaches the limit of diminishing returns, there are no other options. It’s time to solve the intractable problems.

Image credit – Steven Depolo

Hands-On or Hands-Off?

Hands-on versus hands-off – as a leader it’s a fundamental choice. And for me the single most important guiding principle is – do what it takes to maintain or strengthen the team’s personal ownership of the work.

Hands-on versus hands-off – as a leader it’s a fundamental choice. And for me the single most important guiding principle is – do what it takes to maintain or strengthen the team’s personal ownership of the work.

If things are going well, keep your hands off. This reinforces the team’s ownership and your trust in them. But it’s not hands-off in and ignore them sense; it’s hands-off in a don’t tell them what to do sense. Walk around, touch base and check in to show interest in the work and avoid interrogation-based methods that undermine your confidence in them. This is not to say a hands-off leader only superficially knows what’s going on, it should only look like the leader has a superficial understanding.

The hands-off approach requires a deep understanding of the work and the people doing it. The hands-off leader must make the time to know the GPS coordinates of the project and then do reconnaissance work to identify the positions of the quagmires and quicksand that lay ahead. The hands-off leader waits patiently just in front of the obstacles and makes no course correction if the team can successfully navigate the gauntlet. But when the team is about to sink to their waists, leader gently nudges so they skirt the dangerous territory.

Unless, of course, the team needs some learning. And in that case, the leader lets the team march it’s project into the mud. If they need just a bit of learning the leader lets them get a little muddy; and if the team needs deep learning, the leader lets them sink to their necks. Either way, the leader is waiting under cover as they approach the impending snafu and is right beside them to pull them out. But to the team, the hands-off leader is not out in front scouting the new territory. To them, the hands-off leader doesn’t pay all that much attention. To the team, it’s just a coincidence the leader happens to attend the project meeting at a pivotal time and they don’t even recognize when the leader subtly plants the idea that lets the team pull themselves out of the mud.

If after three or four near-drowning incidents the team does not learn or change it’s behavior, it’s time for the hands-off approach to look and feel more hands-on. The leader calls a special meeting where the team presents the status of the project and grounds the project in the now. Then, with everyone on the same page the leader facilitates a process where the next bit of work is defined in excruciating detail. What is the next learning objective? What is the test plan? What will be measured? How will it be measured? How will the data be presented? If the tests go as planned, what will you know? What won’t you know? How will you use the knowledge to inform the next experiments? When will we get together to review the test results and your go-forward recommendations?

By intent, this tightening down does not go unnoticed. The next bit of work is well defined and everyone is clear how and when the work will be completed and when the team will report back with the results. The leader reverts back to hands-off until the band gets back together to review the results where it’s back to hands-on. It’s the leader’s judgement on how many rounds of hands-on roulette the team needs, but the fun continues until the team’s behavior changes or the project ends in success.

For me, leadership is always hands-on, but it’s hands-on that looks like hands-off. This way the team gets the right guidance and maintains ownership. And as long as things are going well this is a good way to go. But sometimes the team needs to know you are right there in the trenches with them, and then it’s time for hands-on to look like hands-on. Either way, its vital the team knows they own the project.

There are no schools that teach this. The only way to learn is to jump in with both feet and take an active role in the most important projects.

Image credit – Kerri Lee Smith

Out of Context

“It’s a fact.” is a powerful statement. It’s far stronger than a simple description of what happened. It doesn’t stop at describing a sequence of events that occurred in the past, rather it tacks on an implication of what to think about those events. When “it’s a fact” there’s objective evidence to justify one way of thinking over another. No one can deny what happened, no one can deny there’s only one way to see things and no one can deny there’s only one way to think. When it’s a fact, it’s indisputable.

“It’s a fact.” is a powerful statement. It’s far stronger than a simple description of what happened. It doesn’t stop at describing a sequence of events that occurred in the past, rather it tacks on an implication of what to think about those events. When “it’s a fact” there’s objective evidence to justify one way of thinking over another. No one can deny what happened, no one can deny there’s only one way to see things and no one can deny there’s only one way to think. When it’s a fact, it’s indisputable.

Facts aren’t indisputable, they’re contextual. Even when an event happens right in front of two people, they don’t see it the same way. There are actually two events that occurred – one for each viewer. Two viewers, two viewing angles, two contexts, two facts. Right at the birth of the event there are multiple interpretations of what happened. Everyone has their own indisputable fact, and then, as time passes, the indisputables diverge.

On their own there’s no problem with multiple diverging paths of indisputable facts. The problem arises when we use indisputable facts of the past to predict the future. Cause and effect are not transferrable from one context to another, even if based on indisputable facts. The physics of the past (in the true sense of physics) are the same as the physics of today, but the emotional, political, organizational and cultural physics are different. And these differences make for different contexts. When the governing dynamics of the past are assumed to be applicable today, it’s easy to assume the indisputable facts of today are the same as yesterday. Our static view of the world is the underlying problem, and it’s an invisible problem.

We don’t naturally question if the context is different. Mostly, we assume contexts are the same and mostly we’re blind to those assumptions. What if we went the other way and assumed contexts are always different? What would it feel like to live in a culture that always questions the context around the facts? Maybe it would be healthy to justify why the learning from one situation applies to another.

As the pace of change accelerates, it’s more likely today’s context is different and yesterday’s no longer applies. Whether we want to or not, we’ll have to get better at letting go of indisputable facts. Instead of assuming things are the same, it’s time to look for what’s different.

Image credit — Joris Leermakers

Are you striving or thriving?

Thriving is not striving. And they’re more than unrealated. They’re opposites.

Thriving is not striving. And they’re more than unrealated. They’re opposites.

Striving is about the now and what’s in it for me. Thriving is about the greater good and choosing – choosing to choose your own path and choosing to travel it in your own way. Thriving doesn’t thrive because outcomes fit with expectations. Thriving thrives on the journey.

Where striving comes at others’ expense, thriving comes at no one’s expense. Where striving strives on getting ahead, thriving thrives on growing. Striving looks outwardly, thriving looks inwardly. No two words are spelled so similarly yet contradict so vehemently.

Plants thrive when they’re put in the right growing conditions. They grow the way they were meant to grow and they don’t look back. They thrive because they don’t second guess themselves. If they don’t grow as tall as others, they’re happy for the tallest. And if they bloom bigger and brighter than the rest, they’re thoughtful enough to make conversation about other things.

Plants and animals don’t strive. Only people do. Strivers live their lives looking through the lens of the zero sum game. Strivers feel there’s not enough sunlight to go around so they reach and stretch and step on your head so they get a tan and leave you to supplement with vitamin D.

I can deal with strivers that tell you they’re going to step on your head and step on it just as they said. And I have immense disdain for strivers that pretend they’re sunflowers. But when I’m around thrivers I resonate.

Strivers suck energy from the room and thrivers give it way freely. And just as the bumblebee gets joy from spreading the love flower-to-flower, thrivers thrive more as they give more.

If you leave a meeting feeling good about yourself and three days later you rethink things and feel like a lesser person, you were victimized by a striver. If you feel great about yourself after a meeting and three days later feel even better, you rubbed shoulders with a thriver.

Learn to spot the strivers so you can distance yourself. And seek out the thrivers so you can grow with them.

Image credit Brad Smith

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski