Archive for the ‘Seeing Things As They Are’ Category

Working with uncertainty

Try – when you’re not sure what to do.

Try – when you’re not sure what to do.

Listen – when you want to learn.

Build – when you want to put flesh on the bones of your idea.

Think – when you want to make progress.

Show a customer – when you want to know what your idea is really worth.

Put it down – when you want your subconscious to solve a problem.

Define – when you want to solve.

Satisfy needs – when you want to sell products

Persevere – when the status quo kicks you in the shins.

Exercise – when you want set the conditions for great work.

Wait – when you want to run out of time and money.

Fear failure – when you want to block yourself from new work.

Fear success – when you want to stop innovation in its tracks.

Self-worth – when you want to overcome fear.

Sleep – when you want to be on your game.

Chance collision – when you want something interesting to work on.

Write – when you want to know what you really think.

Make a hand sketch – when you want to communicate your idea.

Ask for help – when you want to succeed.

Image credit – Daniel Dionne

Rule 1: Allocate resources for effectiveness.

We live in a resource constrained world where there’s always more work than time. Resources are always tighter than tight and tough choices must be made. The first choice is to figure out what change you want to make in the world. How do you want put a dent in the universe? What injustice do you want to put to rest? Which paradigm do you want to turn on its head?

We live in a resource constrained world where there’s always more work than time. Resources are always tighter than tight and tough choices must be made. The first choice is to figure out what change you want to make in the world. How do you want put a dent in the universe? What injustice do you want to put to rest? Which paradigm do you want to turn on its head?

In business and in life, the question is the same – How do you want to spend your time?

Before you can move in the right direction, you need a direction. At this stage, the best way to allocate your resources is to define the system as it is. What’s going on right now? What are the fundamentals? What are the incentives? Who has power? Who benefits when things move left and who loses when things go right? What are the main elements of the system? How do they interact? What information passes between them? You know you’ve arrived when you have a functional model of the system with all the elements, all the interactions and all the information flows.

With an understanding of how things are, how do you want to spend your time? Do you want to validate your functional model? If yes, allocate your resources to test your model. Run small experiments to validate (or invalidate) your worldview. If you have sufficient confidence in your model, allocate your resources to define how things could be. How do you want the fundamentals to change? What are the new incentives? Who do you want to have the power? And what are the new system elements, their new interactions and new information flows?

When working in the domain of ‘what could be’ the only thing to worry about is what’s next. What’s after the next step? Not sure. How many resources will be required to reach the finish line? Don’t know. What do we do after the next step? It depends on how it goes with this step. For those that are used to working within an efficiency framework this phase is a challenge, as there can be no grand plan, no way to predict when more resources will be needed and no way to guarantee resources will work efficiently. For the ‘what could be’ phase, it’s better to use a framework of effectiveness.

In a one-foot-in-front-of-the-other way, the only thing that matters in the ‘what could be’ domain is effectively achieving the next learning objective. It’s not important that the learning is done most efficiently, it matters that the learning is done well and done quickly. Efficiently learning the wrong thing is not effective. Running experiments efficiently without learning what you need to is not effective. And learning slowly but efficiently is not effective.

Allocate resources to learn what needs to be learned. Allocate resources to learn effectively, not efficiently. Allocate your best people and give them the time they need. And don’t expect an efficient path. There will be unplanned lefts and rights. There will be U-turns. There will times when there’s lots of thinking and little activity, but at this stage activity isn’t progress, thinking is. It may look like a drunkard’s walk, but that’s how it goes with this work.

When the objective of the work isn’t to solve the problem but to come up with the right question, allocate resources in a way that prioritizes effectiveness over efficiency. When working in the domain of ‘what could be’ allocate resources on the learning objective at hand. Don’t worry too much about the follow-on learning objectives because you may never earn the right to take them on.

In the domain of uncertainty, the best way to allocate the resources is to learn what you need to learn and then figure out what to learn next.

Image credit – John Flannery

What’s an innovator to do?

Disruption, as a word, doesn’t tell us what to do or how to do it. Disruption, as a word, it’s not helpful and should be struck from the innovation lexicon. But without the word, what’s an innovator to do?

Disruption, as a word, doesn’t tell us what to do or how to do it. Disruption, as a word, it’s not helpful and should be struck from the innovation lexicon. But without the word, what’s an innovator to do?

If you have a superpower, misuse it. Your brand’s special capability is well known in your industry, but not in others. Thrust your uniqueness into an unsuspecting industry and provide novel value in novel ways. Take it by storm. Contradict the established players. Build momentum quickly and quietly. Create a step function improvement. Create new lines of customer goodness. Do things that haven’t been done. Turn no to yes.

Don’t adapt your special capability, use it as-is. Adaptation is good, but it’s better to flop the whole thing into the new space. Don’t think graft, think transplant. Adaptation brings only continuous improvement. It’s better to serve up your secret sauce uncut and unfiltered because that brings discontinuous improvement.

Know the needs your product fulfills and meet those needs in another industry. Some say it’s better to adapt your product to other industries, and to achieve a reasonable CAGR, adaptation is good. But if you’re looking for an unreasonable CAGR, if you’re looking to stand things on their head, try to use your product as-is. When you can use your product as-is in another industry, you connect dots only you can connect and meet needs in ways only you can. You bring non-intuitive solutions. You violate routines of accepted practice and your trajectory is not limited by the incumbents’ ruts of success. You’ll have a whole new space for yourself. No sharing required.

But how?

Simply and succinctly, define what your product does. Then, make it generic and look to misapply the goodness in a different application. For example, manufacturers of large and expensive furniture wrap their products in huge plastic bags to keep the furniture dry and clean during shipping. Generically, the function becomes: use large plastic bags to temporarily protect large and expensive products from becoming wet. Using that goodness in a new application, people who live in flood areas use the large furniture bags to temporarily protect their cars from water damage. Just before the flood arrives, they drive their cars into large plastic bags and tie them off. The bags keep their car dry when the water comes. Same bag, same goodness, completely unrelated application.

And there’s another way. Your product has a primary function that provides value to your customers. But, there is unrealized value in your product that your existing customers don’t value. For example, if your company has a proprietary process to paint products in a way that results in a high gloss finish, your customers buy your coating because it looks good. But, the coating may also create a hard layer and increase wear resistance that could be important in another application. Because your coating is environmentally friendly and your process is low-cost, new customers may want you to coat their parts so they can be used in a previously non-viable application. There is unrealized value in your products that new customers will pay for.

To see the unrealized value, use the strength-as-a-weakness method. Define two constraints: you must sell to new customers in a new industry and the primary goodness, why people buy your product, must be a weakness. For example, if your product is fast, you’ve got to use unrealized value to sell a slow one. If it’s heavy, the new one must be light. If small, the new one must be large. In that way, you are forced to rely on new lines of goodness and unrealized value to sell your product.

Don’t stop continuous improvement and product adaptation. They’re valuable. But, start some discontinuous improvement, step function increases and purposeful misuse. Keep selling to the same value to the same customers, but start selling to new customers with previously unrealized value that has been hiding quietly in your product for years.

Evolution is good, but exaptation is probably better.

Image credit – Sor Betto

See differently to solve differently.

There are many definitions for creativity and innovation, but none add meaningfully to how the work is done. Though it’s clear why the work is important – creativity and innovation underpin corporate prosperity and longevity – it’s especially helpful to know how to do it.

There are many definitions for creativity and innovation, but none add meaningfully to how the work is done. Though it’s clear why the work is important – creativity and innovation underpin corporate prosperity and longevity – it’s especially helpful to know how to do it.

At the most basic level, creativity and innovation are about problem solving. But it’s a special flavor of problem solving. Creativity and innovation are about problems solving new problems in new ways. The glamorous part is ‘solving in new ways’ and the important part is solving new problems.

With continuous improvement the same problems are solved over and over. Change this to eliminate waste, tweak that to reduce variation, adjust the same old thing to make it work a little better. Sure, the problems change a bit, but they’re close cousins to the problems to the same old problems from last decade. With discontinuous improvement (which requires high levels of creativity and innovation) new problems are solved. But how to tell if the problem is new?

Solving new problems starts with seeing problems differently.

Systems are large and complicated, and problems know how to hide in the nooks and crannies. In a Where’s Waldo way, the nugget of the problem buries itself in complication and misuses all the moving parts as distraction. Problems use complication as a cloaking mechanism so they are not seen as problems, but as symptoms.

Telescope to microscope. To see problems differently, zoom in. Create a hand sketch of the problem at the microscopic level. Start at the system level if you want, but zoom in until all you see is the problem. Three rules: 1. Zoom in until there are only two elements on the page. 2. The two elements must touch. 3. The problem must reside between the two elements.

Noun-verb-noun. Think hammer hits nail and hammer hits thumb. Hitting the nail is the reason people buy hammers and hitting the thumb is the problem.

A problem between two things. The hand sketch of the problem would show the face of the hammer head in contact with the surface of the thumb, and that’s all. The problem is at the interface between the face of the hammer head and the surface of the thumb. It’s now clear where the problem must be solved. Not where the hand holds the shaft of the hammer, not at the claw, but where the face of the hammer smashes the thumb.

Before-during-after. The problem can be solved before the hammer smashes the thumb, while the hammer smashes the thumb, or after the thumb is smashed. Which is the best way to solve it? It depends, that’s why it must be solved at the three times.

Advil and ice. Solving the problem after the fact is like repair or cleanup. The thumb has been smashed and repercussions are handled in the most expedient way.

Put something between. Solving the problem while it happens requires a blocking or protecting action. The hammer still hits the thumb, but the protective element takes the beating so the thumb doesn’t.

Hand in pocket. Solving the problem before it happens requires separation in time and space. Before the hammer can smash the thumb it is moved to a safe place – far away from where the hammer hits the nail.

Nail gun. If there’s no way for the thumb to get near the hammer mechanism, there is no problem.

Cordless drill. If there are no nails, there are no hammers and no problem.

Concrete walls. If there’s no need for wood, there’s no need for nails or a hammer. No hammer, no nails, no problem.

Discerning between symptoms and problems can help solve new problems. Seeing problems at the micro level can result in new solutions. Looking closely at problems to separate them time and space can help see problems differently.

Eliminating the tool responsible for the problem can get rid of the problem of a smashed thumb, but it creates another – how to provide the useful action of the driven nail. But if you’ve been trying to protect thumbs for the last decade, you now have a chance to design a new way to fasten one piece of wood to another, create new walls that don’t use wood, or design structures that self-assemble.

Image credit – Rodger Evans

The Effective Expert

What if you’re asked to do something you know isn’t right? Not from an ethical perspective, but from a well-read, well-practiced, world-thought-leader perspective? What if you know it’s a waste of time? What if you know it sets a dangerous precedent for doing the wrong work for the right reason? What if the person asking is in a position of power? What if you know they think they’re asking for the right work?

What if you’re asked to do something you know isn’t right? Not from an ethical perspective, but from a well-read, well-practiced, world-thought-leader perspective? What if you know it’s a waste of time? What if you know it sets a dangerous precedent for doing the wrong work for the right reason? What if the person asking is in a position of power? What if you know they think they’re asking for the right work?

Do you delay and make up false reasons for the lack of progress? Do you get angry because you expect people in power know what they’re doing? Does your anger cause you to double-down on delay? Or does it cause you to take a step back and regroup? Or do you give them what they ask for, knowing it will make it clear they don’t know what they’re doing?

What if you asked them why they want what they want? What if when you really listened you heard their request for help? What if you recognized they weren’t comfortable confiding in you and that’s why they didn’t tell you they needed your help? What if you could see they did not know how to ask? What if you realized you could help? What if you realized you wanted to help?

What if you honored their request and took an approach that got the right work done? What if you used their words as the premise and used your knowledge and kindness to twist the work into what it should be? What if you realized they gave you a compliment when they asked you to do the work? Better still, what if you realized you were the only person who could help and you felt good about your realization?

As subject matter experts, it’s in our best interest to have an open mind and an open heart. Sure, it’s important to hang onto our knowledge, but it’s also important to let go our strong desire to be right and do all we can to improve effectiveness.

If we are so confident in our knowledge, shouldn’t it be relatively easy to give others the benefit of the doubt and be respectful of the possibility there may be a deeper fundamental behind the request for the “wrong work”?

As subject matter experts, our toughest job is to realize we don’t always see the whole picture and things aren’t always as they seem. And to remain open, it’s helpful to remember we became experts by doing things wrong. And to prioritize effectiveness, until proven otherwise, it’s helpful to assume everyone has good intentions.

Image credit — Ingrid Taylar

Innovation and the Mythical Idealized Future State

When it’s time to innovate, the first task is usually to define the Idealized Future State (IFS). The IFS is a word picture that captures what it looks like when the innovation work has succeeded beyond our wildest dreams. The IFS, so it goes, is directional so we can march toward the right mountain and inspirational so we can sustain our pace over the roughest territory.

When it’s time to innovate, the first task is usually to define the Idealized Future State (IFS). The IFS is a word picture that captures what it looks like when the innovation work has succeeded beyond our wildest dreams. The IFS, so it goes, is directional so we can march toward the right mountain and inspirational so we can sustain our pace over the roughest territory.

For the IFS to be directional, it must be aimed at something – a destination. But there’s a problem. In a sea of uncertainty, where the work has never been done before and where there are no existing products, services or customers, there are an infinite number of IFRs/destinations to guide our innovation work. Open question – When the territory is unknown, how do we choose the right IFS?

For the IFS to be inspirational, it must create yearning for something better (the destination). And for the yearning to be real, we must believe the destination is right for us. Open question – How can we yearn for an IFS when we really can’t know it’s the right destination?

Maps aren’t the territory, but they are a collection of all possible destinations within the design space of the map. If you have the right map, it contains your destination. And for a long time now, the old paper maps have helped people find their destinations. But on their own maps don’t tell us the direction to drive. If you have a map of the US and you want to drive to Kansas, in which direction do you drive? It depends. If in California, drive east; if in Mississippi, drive north; if in New Hampshire, drive west; and in Minnesota, drive south. If Kansas is your idealized future state, the map alone won’t get your there. The direction you drive depends on your location.

GPS has been a nice addition to maps. Enter the destination on the map, ask the satellites to position us globally and it’s clear which way to drive. (I drive west to reach Kansas.) But the magic of GPS isn’t in the electronic map, GPS is magic because it solves the location problem.

Before defining the idealized future state, define your location. It grounds the innovation work in the reality of what is, and people can rally around what is. And before setting the innovation direction with the IFS, define the next problems to solve and walk in their direction.

Image credit – Adrian Brady

Forecasting The Next Big Technology

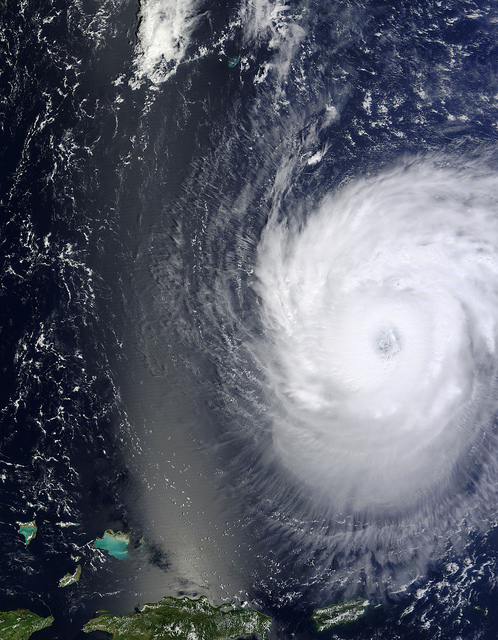

When a hurricane is on the horizon, we are all glued to our TVs. We want to know where it track so we know we’ll be safe. Will it track north and rumble over the top of us or will it track east and head out to sea? This is not trivial. In one scenario we lose our house and in the other the crazy surfers get to ride huge waves.

When a hurricane is on the horizon, we are all glued to our TVs. We want to know where it track so we know we’ll be safe. Will it track north and rumble over the top of us or will it track east and head out to sea? This is not trivial. In one scenario we lose our house and in the other the crazy surfers get to ride huge waves.

The meteorologist shows us a time-lapse of the storm center hour-by-hour. It was one hundred miles off shore an hour ago, it’s fifty miles off shore now and it will hit the shoreline in an hour. Drawing a line from where it was, through its location in the moment, the meteorologist can extrapolate where it will be an hour from now. In the short term, the storms trajectory will be unchanged and its momentum will help it maintain its pace. It’s pretty clear to everyone where the storm will be in an hour. No magic here.

But the good meteorologists can forecast a hurricane’s path days in advance. In a phenomenological way, they use behavior models of past storms, assume this storm is like past storms, turn the crank and forecast its trajectory. And they’re right more times than not. And they’re right enough to determine who should evacuate and who should sit tight. This is borderline magic.

The best meteorologists know where hurricanes want go because they understand hurricanes. They know hurricanes want to run in straight lines, if not follow gentle curves. They know hurricanes get anxious when they hop from sea to land, and they know, given the choice, will skirt the coastline and head back home to the salt water. Meteorologists know the rules hurricane’s live by and use that knowledge to tighten their forecast of the storm’s path.

Just as hurricanes have a desire to follow their hearts, technologies have a similar desire climb the evolutionary ladder. Just as hurricanes behave like their predecessors, technologies behave like their grandparents, aunts and uncles. And just as a meteorologist, using their knowledge of historical patterns and an understanding of hurricane genetics can forecast the path of a hurricane, technologists can forecast the path of technologies using historical patterns and an understanding of what technologies want.

And like with hurricanes, the best way to forecast the path of a technology is to define where it was, draw a line through where it is and project its trajectory into the future. Like hurricanes, technologies move in straight lines or gentle S-curves, so their next move is easy to forecast. If a technology has improved year-over-year, it will likely continue to improve. And if this year’s performance is the same as last year, it’s behavior will remain unchanged going forward. That’s how it goes with technologies.

The best technologists are like horse whisperers in that they can hear the inner voice of technologies. They know when a technology is ready to grow from infant to adolescent and know when a technology is ready to retire. The best technologists can read the tea leaves of the patent landscape and, knowing the predisposition of technologies, can forecast the next evolution. But just as some ranch owners don’t believe in horse whisperers, some company leaders don’t believe technology whisperers can forecast technologies.

But for believers and non-believers alike, it’s more effective to compare forecasting capabilities of technologists with the forecasting capabilities of meteorologists. The notions of trajectory and momentum have clear physical interpretations for hurricanes and technologies, and historical models of storm trajectories map directly to evolutionary paths of technologies.

If you’re looking to forecast where the next big storm will make landfall, hire a great meteorologist. But if you’re looking to forecast when the next technology will rip the roof off your business model, hire a great technology whisperer.

Image credit – NASA

Improving What Is and Creating What Isn’t

There are two domains – what is and what isn’t. We’re most comfortable in what is and we don’t know much about what isn’t. Neither domain is best and you can’t have one without the other. Sometimes it’s best to swim in what is and other times it’s better to splash around in what isn’t. Though we want them, there are no hard and fast rules when to swim and when to splash.

Improvement lives in the domain of what is. If you’re running a Six Sigma project, a lean project or a continuous improvement program you’re knee deep in what is. Measure, analyze, improve, and control what is. Walk out to the production floor, count the machines, people and defects, measure the cycle time and eliminate the wasteful activities. Define the current state and continually (and incrementally) improve what is. Clear, unambiguous, measurable, analytical, rational.

The close cousins creativity and innovation live in the domain of what isn’t. They don’t see what is, they only see gaps, gulfs and gullies. They are drawn to the black hole of what’s missing. They define things in terms of difference. They care about the negative, not the image. They live in the Bizarro world where strength is weakness and far less is better than less. Unclear, ambiguous, intuitive, irrational.

What is – productivity, utilization, standard work. What isn’t – imagination, unstructured time, daydreaming. Predictable – what is. Unknowable – what isn’t.

In the world of what is, it’s best to hire for experience. What worked last time will work this time. The knowledge of the past is all powerful. In the world of what isn’t, it’s best to hire young people that know more than you do. They know the latest technology you’ve never heard of and they know its limitations.

Improving what is pays the bills while creating what isn’t fumbles to find the future. But when what is runs out of gas, what isn’t rides to the rescue and refuels. Neither domain is better, and neither can survive without the other.

The magic question – what’s the best way to allocate resources between the domains? The unsatisfying answer – it depends. And the sextant to navigate the dependencies – good judgement.

Image credit – JD Hancock

With innovation, it depends.

By definition, when the work is new there is uncertainty. And uncertainty can be stressful. But, instead of getting yourself all bound up, accept it. More than that, relish in it. Wear it as a badge of honor. Not everyone gets the chance to work on something new – only the best do. And, because you’ve been asked to do work with a strong tenor of uncertainty, someone thinks you’re the best.

By definition, when the work is new there is uncertainty. And uncertainty can be stressful. But, instead of getting yourself all bound up, accept it. More than that, relish in it. Wear it as a badge of honor. Not everyone gets the chance to work on something new – only the best do. And, because you’ve been asked to do work with a strong tenor of uncertainty, someone thinks you’re the best.

But uncertainty is an unknown quantity, and our systems have been designed to reject it, not swim in it. When companies want to get serious they drive toward a culture of accountability and the new work gets the back seat. Accountability is mis-mapped to predictability, successful results and on time delivery. Accountability, as we’ve mapped it, is the mortal enemy of new work. When you’re working on a project with a strong element of uncertainty, the only certainty is the task you have in front of you. There’s no certainty on how the task will turn out, rather, there’s only the simple certainty of the task.

With work with low uncertainty there are three year plans, launch timelines and predictable sales figures. Task one is well-defined and there’s a linear flow of standard work right behind it – task two through twenty-two are dialed in. But when working with uncertainty, the task at hand is all there is. You don’t know the next task. When someone asks what’s next the only thing you can say is “it depends.” And that’s difficult in a culture of traditional accountability.

An “it depends” Gannt chart is an oxymoron, but with uncertainty step two is defined by step one. If A, then B. But if the wheels fall off, I’m not sure what we’ll do next. The only thing worse than an “it depends” Gantt chart is an “I’m not sure” Gannt chart. But with uncertainty, you can be sure you won’t be sure. With uncertainty, traditional project planning goes out the window, and “it depends” project planning is the only way.

With uncertainty, traditional project planning is replaced by a clear distillation of the problem that must be solved. Instead of a set of well-defined tasks, ask for a block diagram that defines the problem that must be solved. And when there’s clarity and agreement on the problem that must be solved, the supporting tasks can be well-defined. Step one – make a prototype like this and test it like that. Step two – it depends on how step one turns out. If it goes like this then we’ll do that. If it does that, we’ll do the other. And if it does neither, we’re not sure what we’ll do. You don’t have to like it, but that’s the way it is.

With uncertainty, the project plan isn’t the most important thing. What’s most important is relentless effort to define the system as it is. Here’s what the system is doing, here’s how we’d like it to behave and, based on our mechanism-based theory, here’s the prototype we’re going to build and here’s how we’re going to test it. What are we going to do next? It depends.

What’s next? It depends. What resources do you need? It depends. When will you be done? It depends.

Innovation is, by definition, work that is new. And, innovation, by definition, is uncertain. And that’s why with innovation, it depends. And that’s why innovation is difficult.

And that’s why you’ve got to choose wisely when you choose the people that do your innovation work.

Image credit – Sara Biljana Gaon (off)

The Causes and Conditions for Innovation

Everyone wants to do more innovation. But how? To figure out what’s going on with their innovation programs, companies spend a lot of time to put projects into buckets but this generates nothing but arguments about whether projects are disruptive, radical innovation, discontinuous, or not. Such a waste of energy and such a source of conflict. Truth is, labels don’t matter. The only thing that matters is if the projects, as a collection, meet corporate growth objectives. Sure, there should be a short-medium-long look at the projects, but, for the three time horizons the question is the same – Do the projects meet the company’s growth objectives?

Everyone wants to do more innovation. But how? To figure out what’s going on with their innovation programs, companies spend a lot of time to put projects into buckets but this generates nothing but arguments about whether projects are disruptive, radical innovation, discontinuous, or not. Such a waste of energy and such a source of conflict. Truth is, labels don’t matter. The only thing that matters is if the projects, as a collection, meet corporate growth objectives. Sure, there should be a short-medium-long look at the projects, but, for the three time horizons the question is the same – Do the projects meet the company’s growth objectives?

To create the causes and conditions for innovation, start with a clear growth objective by geography. Innovation must be measured in dollars.

Good judgement is required to decide if a project is worthy of resources. The incremental sales estimates are easy to put together. The difficult parts are deciding if there’s enough sizzle to cause customers to buy and deciding if the company has the chops to do the work. The difficulty isn’t with the caliber of judgement, rather it’s insufficient information provided to the people that must use their good judgement. In shorth, there is poor clarity on what the projects are about. Any description of the projects blurry and done at a level of abstraction that’s too high. Good judgement can’t be used when the picture is snowy, nor can it be effective with a flyby made in the stratosphere.

To create the causes and conditions for innovation, demand clarity and bedrock-level understanding.

To guarantee clarity and depth, use the framework of novel, useful, successful. Give the teams a tight requirement for clarity and depth and demand they meet it. For each project, ask – What is the novelty? How is it useful? When the project is completed, how will everyone be successful?

A project must deliver novelty and the project leader must be able to define it on one page. The best way to do this is to create physical (functional) model of the state-of-the-art system and modify it with the newness created by the project (novelty called out in red). This model comes in the form of boxes that describe the system elements (simple nouns) and arrows that define the actions (simple verbs). Think hammer (box – simple noun) hits (arrow -simple verb) nail (box – simple noun) as the state-of-the-art system and the novelty in red – a thumb protector (box) that blocks (arrow) hammer (box). The project delivers a novel thumb protector that prevents a smashed thumb. The novelty delivered by the project is clear, but does it pass the usefulness test?

To create the causes and conditions for innovation, demand a one-page functional model that defines and distills down to bedrock level the novelty created by the project. And to help the project teams do it, hire a good teach teacher and give them the tools, time and training.

The novelty delivered by a project must be useful and the project leader must clearly define the usefulness on one page. The best way to do this is with a one page hand sketch showing the customer actively using the novelty. In a jobs-to-be-done way, the sketch must define where, when and how the customer will realize the usefulness. And to force distillation blinding, demand they use a fat, felt tip marker. With this clarity, leaders with good judgement can use their judgement effectively. Good questions flow freely. Does every user of a hammer need this? Can a left-handed customer use the thumb guard? How does it stay on? Doesn’t it get in the way? Where do they put it when they’re done? Do they wear it all the time? With this clarity, the questions are so good there is no escape. If there are holes they will be uncovered.

To create the causes and conditions for innovation, demand a one-page hand sketch of the customer demonstrating the useful novelty.

To be successful, the useful novelty must be sufficiently meaningful that customers pay money for it. The standard revenue projections are presented, but, because there is deep clarity on the novelty and usefulness, there is enough context for good judgement to be effective. What fraction of hammer users hit their thumbs? How often? Don’t they smash their fingers too? Why no finger protection? Because of the clarity, there is no escape.

To create the causes and conditions, use the deep clarity to push hard on buying decisions and revenue projections.

The novel, useful, successful framework is a straightforward way to decide if the project portfolio will meet growth objectives. It demands a clear understanding of the newness created by the project but, in return, provides context needed to use good judgement. In that way, because projects cannot start without passing the usefulness and successfulness tests, resources are not allocated to unworthy projects.

But while clarity and this level of depth is a good start, it’s not enough. It’s time for a deeper dive. The project must distill the novelty into a conflict diagram, another one-pager like the others, but deeper. Like problem definition on steroids, a conflict must be defined in space – between two things (thumb and face of hammer head) – and time (just as the hammer hits thumb). With that, leaders can ask before-during-after questions. Why not break the conflict before it happens by making a holding mechanism that keeps the thumb out of the strike zone? Are you sure you want to solve it during the conflict time (when the hammer hits thumb)? Why not solve it after the fact by selling ice packs for their swollen thumbs?

But, more on the conflict domain at another time.

For now, use novel, useful, successful to stop bad projects and start good ones.

Image credit – Natashi Jay

Understanding the trajectory of the competitive landscape

If you want to gain ground on your competition you’ve first got to know where things stand. Where are their advantages? Where are your advantages? Where is there parity? To quickly understand the situations there are three tricks: stay at a high level, represent the situation in a clear way and, where possible, use public information from their website.

If you want to gain ground on your competition you’ve first got to know where things stand. Where are their advantages? Where are your advantages? Where is there parity? To quickly understand the situations there are three tricks: stay at a high level, represent the situation in a clear way and, where possible, use public information from their website.

A side-by-side comparison of the two companies’ products is the way to start. Create a common set of axes with price running south to north and performance (or output) running west to east. Make two copies and position them side-by-side on the page – yours on the left and theirs directly opposite on the right. Go to their website (and yours) and make a list of every product, its price and its output. (For prices of their products you may have to engage your sales team and your customers.) For each of your products place a symbol (the company logo) on your performance-price landscape and do the same for their products on their landscape. It’s now clear who has the most products, where their portfolio outflanks yours and where you outflank them. The clarity and simplicity will help everyone see things as they are – there may be angst but there will be no confusion and no disagreement. The picture is clear. But it’s static.

The areal differences define the gaps to close and the advantages to exploit. Now it’s time to define the momentum and trajectories of the portfolios to add a dynamic element. For your most recent product launch add a one next to its logo, for the second most recent add a two and for the third add three. These three regions of your portfolio are your most recent focus areas. This is your trajectory and this is where you have momentum. Extend and arrow in the direction of your trajectory. If you stay the course, this is where your portfolio will add mass. Do the same for your competitor and compare arrows. You know have a glimpse into the future. Are your arrows pointing in the same directions as theirs? Are they located in the same regions? How would feel if both companies continued on their trajectories? With this addition you have glimpse into the stay-the-course future. But will they stay the course? For that you need to look at the patent landscape.

Do a patent search on their patents and applications over the previous year and represent each with its most descriptive figure. Write a short thematic description for each, group like themes and draw a circle around them. Mark the circle with a one to denote last year’s patents. Repeat the process for two years ago and three years ago and mark each circle accordingly. Now you have objective evidence of the future. You know where they have been working and you know where they want to go. You have more than a glimpse into the future. You know their preferred trajectories. Reconcile their preferred trajectories with their price-performance landscapes and arrows 1, 2 and 3. If their preferred trajectories line up with their product momentum, it’s business as usual for them. If they contradict, they are playing a different game. And because it takes several years for patent applications to publish, they’ve been playing a new game for a while now.

Repeat the process for your patent landscape and flop it onto your performance-price landscape. I’m not sure what you’ll see, but you’ll know it when you see it. Then, compare yours with theirs and you’ll know what the competitive landscape will look like in three years. You may like what you see, or not. But, the picture will be clear. There may be discomfort, but there can be no arguments.

This process can also be used in the acquisition process to get a clear picture a company’s future state. In that way you can get a calibrated view three years into the future and use your crystal ball to adjust your offer price accordingly.

Image credit – Rob Ellis

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski