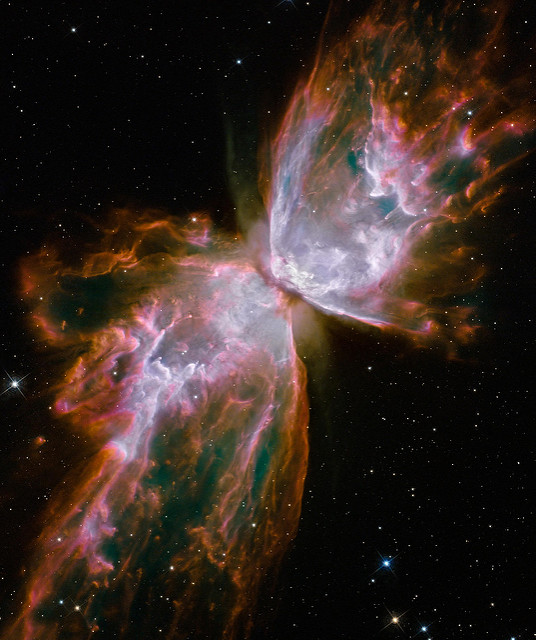

Archive for the ‘Seeing Things As They Are’ Category

To figure out what’s next, define the system as it is.

Every day starts and ends in the present. Sure, you can put yourself in the future and image what it could be or put yourself in the past and remember what was. But, neither domain is actionable. You can’t change the past, nor can you control the future. The only thing that’s actionable is the present.

Every day starts and ends in the present. Sure, you can put yourself in the future and image what it could be or put yourself in the past and remember what was. But, neither domain is actionable. You can’t change the past, nor can you control the future. The only thing that’s actionable is the present.

Every morning your day starts with the body you have. You may have had a more pleasing body in the past, but that’s gone. You may have visions of changing your body into something else, but you don’t have that yet. What you do today is governed and enabled by your body as it is. If you try to lift three hundred pounds, your system as it is will either pick it up or it won’t.

Every morning your day starts with the mind you have. It may have been busy and distracted in the past and it may be calm and settled in the future, but that doesn’t matter. The only thing that matters is your mind as it is. If you respond kindly, today’s mind is responsible, and if your response is unkind, today’s mind system is the culprit. Like it or not, your thoughts, feelings and actions are the result of your mind as it is.

Change always starts with where you are, and the first step is unclear until you assess and define your systems as they are. If you haven’t worked out in five years, your first step is to see your doctor to get clearance (professional assessment) for your upcoming physical improvement plan. If you’ve run ten marathons over the last ten months, your first step may be to take a month off to recover. The right next step starts with where you are.

And it’s the same with your mind. If your mind is all over the place your likely first step is to learn how to help it settle down. And once it’s a little more settled, your next step may be to use more advanced methods to settle it further. And if you assess your mind and you see it needs more help than you can give it, your next step is to seek professional help. Again, your next step is defined by where you are.

And it’s the same with business. Every morning starts with the products and services you have. You can’t sell the obsolete products you had, nor can you sell the future services you may develop. You can only sell what you have. But, in parallel, you can create the next product or system. And to do that, the first step is to take a deep, dispassionate look at the system as it is. What does it do well? What does it do poorly? What can be built on and what can be discarded? There are a number of tools for this, but more important than the tools is to recognize that the next one starts with an assessment of the one you have.

If the existing system is young and immature, the first step is likely to nurture it and support it so it can grow out of its adolescence. But the first step is NOT to lift three hundred pounds because the system-as it is-can only lift fifty. If you lift too much too early, you’ll break its back.

If the existing system is in it’s prime and has been going to the gym regularly for the last five years, its ready for three hundred pounds. Go for it! But, in parallel, it’s time to start a new activity, one that will replace the weightlifting when the system can no longer lift like it used to. Maybe tennis? But start now because to get good at tennis requires new muscles and time.

And if the existing system is ready for retirement, retire it. Difficult to do, but once there’s public acknowledgement, the retirement will take care of itself.

If you want to know what’s next, define the system as it is. The next step will be clear.

And the best time to do it is now.

Image credit – NASA

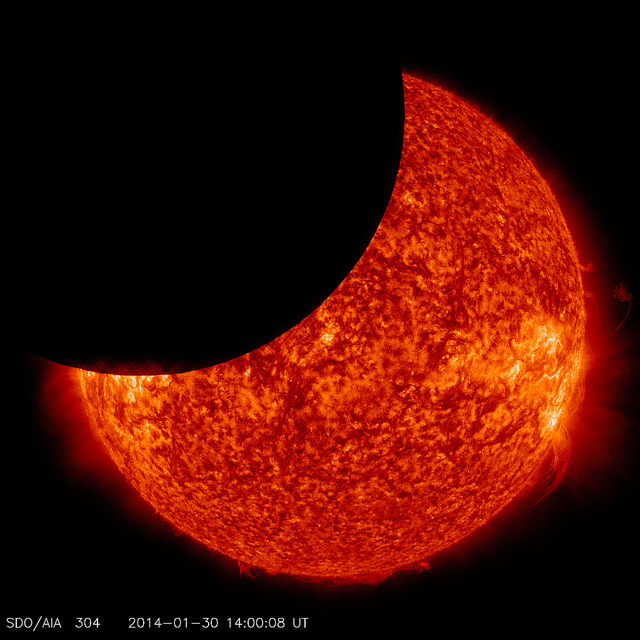

The right time horizon for technology development

Patents are the currency of technology and profits are the currency of business. And as it turns out, if you focus on creating technology you’ll get technology (and patents) and if you focus on profits you’ll get profits. But if no one buys your technology (in the form of the products or services that use it), you’ll go out of business. And if you focus exclusively on profits you won’t create technology and you’ll go out of business. I’m not sure which path is faster or more dangerous, but I don’t think it matters because either way you’re out of business.

Patents are the currency of technology and profits are the currency of business. And as it turns out, if you focus on creating technology you’ll get technology (and patents) and if you focus on profits you’ll get profits. But if no one buys your technology (in the form of the products or services that use it), you’ll go out of business. And if you focus exclusively on profits you won’t create technology and you’ll go out of business. I’m not sure which path is faster or more dangerous, but I don’t think it matters because either way you’re out of business.

It’s easy to measure the number of patents and easier to measure profits. But there’s a problem. Not all patents (technologies) are equal and not all profits are equal. You can have a stockpile of low-level patents that make small improvements to existing products/services and you can have a stockpile of profits generated by short-term business practices, both of which are far less valuable than they appear. If you measure the number of patents without evaluating the level of inventiveness, you’re running your business without a true understanding of how things really are. And if you’re looking at the pile of profits without evaluating the long-term viability of the engine that created them you’re likely living beyond your means.

In both cases, it’s important to be aware of your time horizon. You can create incremental technologies that create short term wins and consume all your resource so you can’t work on the longer-term technologies that reinvent your industry. And you can implement business practices that eliminate costs and squeeze customers for next-quarter sales at the expense of building trust-based engines of growth. It’s all about opportunity cost.

It’s easy to develop technologies and implement business processes for the short term. And it’s equally easy to invest in the long term at the expense of today’s bottom line and payroll. The trick is to balance short against long.

And for patents, to achieve the right balance rate your patents on the level of inventiveness.

Image credit – NASA’s Solar Dynamics Observatory

Is your tank empty?

Sometimes your energy level runs low. That’s not a bad thing, it’s just how things go. Just like a car’s gas tank runs low, our gas tanks, both physical and emotional, also need filling. Again, not a bad thing. That’s what gas tanks are for – they hold the fuel.

Sometimes your energy level runs low. That’s not a bad thing, it’s just how things go. Just like a car’s gas tank runs low, our gas tanks, both physical and emotional, also need filling. Again, not a bad thing. That’s what gas tanks are for – they hold the fuel.

We’re pretty good at remembering that a car’s tank is finite. At the start of the morning commute, the car’s fuel gauge gives a clear reading of the fuel level and we do the calculation to determine if we can make it or we need to stop for fuel. And we do the same thing in the evening – look at the gauge, determine if we need fuel and act accordingly. Rarely we run the car out of fuel because the car continuously monitors and displays the fuel level and we know there are consequences if we run out of fuel.

We’re not so good at remembering our personal tanks are finite. At the start of the day, there are no objective fuel gauges to display our internal fuel levels. The only calculation we make – if we can make it out of bed we have enough fuel for the day. We need to do better than that.

Our bodies do have fuel gages of sorts. When our fuel is low we can be irritable, we can have poor concentration, we can be easily distracted. Though these gages are challenging to see and difficult to interpret, they can be used effectively if we slow down and be in our bodies. The most troubling part has nothing to do with our internal fuel gages. Most troubling is we fail to respect their low fuel warnings even when we do recognize them. It’s like we don’t acknowledge our tanks are finite.

We don’t think our cars are flawed because their fuel tanks run low as we drive. Yet, we see the finite nature of our internal fuel tanks as a sign of weakness. Why is that? Rationally, we know all fuel tanks are finite and their fuel level drops with activity. But, in the moment, when are tanks are low, we think something is wrong with us, we think we’re not whole, we think less of ourselves.

When your tank is low, don’t curse, don’t blame, don’t feel sorry and don’t judge. It’s okay. That’s what tanks do.

A simple rule for all empty tanks – put fuel in them.

Image credit – Hamed Saber

Choosing What To Do

In business you’ve got to do two things: choose what to do and choose how to do it well. I’m not sure which is more important, but I am sure there’s far more written on how to do things well and far less clarity around how to choose what to do.

In business you’ve got to do two things: choose what to do and choose how to do it well. I’m not sure which is more important, but I am sure there’s far more written on how to do things well and far less clarity around how to choose what to do.

Choosing what to do starts with understanding what’s being done now. For technology, it’s defining the state-of-the-art. For the business model, it’s how the leading companies are interacting with customers and which functions they are outsourcing and which they are doing themselves. In neither case does what’s being done define your new recipe, but in both cases it’s the first step to figuring how you’ll differentiate over the competition.

Every observation of the state-of-the-art technologies and latest business models is a snapshot in time. You know what’s happening at this instant, but you don’t know what things will look like in two years when you launch. And that’s not good enough. You’ve got to know the improvement trajectories; you’ve got to know if those trajectories will still hold true when you’ll launch your offering; and, if they’re out of gas, you’ve got to figure out the new improvement areas and their trajectories.

You’ve got to differentiate over the in-the-future competition who will constantly improve over the next two years, not the in-the-moment competition you see today.

For technology, first look at the competitions’ websites. For their latest product or service, figure out what they’re proud of, what they brag about, what line of goodness it offers. For example, is it faster, smaller, lighter, more powerful or less expensive? Then, look at the product it replaced and what it offered. If the old was faster than the one it replaced and the newest one was faster still, their next one will try to be faster. But if the old one was faster than the one it replaced and the newest one is proud of something else, it’s likely they’ll try to give the next one more of that same something else.

And the rate of improvement gives another clue. If the improvement is decreasing over time (old product to new product), it’s likely the next one will improve on a new line of goodness. If it’s still accelerating, expect more of what they did last time. Use the slope to estimate the magnitude of improvement two years from now. That’s what you’ve got to be better than.

And with business models, make a Wardley Map. On the map, place the elements of the business ecosystem (I hate that word) and connect the elements that interact with each other. And now the tricky part. Move to the right the mature elements (e.g., electrical power grid), move to the middle the immature elements (things that are clunky and you have to make yourself) and move to the middle the parts you can buy from others (products). There’s a north-south element to the maps, but that’s for another time.

The business model is defined by which elements the company does itself, which it buys from others and which new ones they create in their labs. So, make a model for each competitor. You’ll be able to see their business model visually.

Now, which elements to work on? Buy the ones you can buy (middle), improve the immature ones on the far left so they move toward the central region (product) and disrupt the lazy utilities (on the right) with some crazy technology development and create something new on the far left (get something running in the lab).

Choosing what to work on starts with Observation of what’s going on now. Then, that information is Oriented with analysis, synthesis and diverse perspective. Then, using the best frameworks you know, a Decision is made. And then, and only then, can you Act.

And there you have it. The makings of an OODA loop-based methodology for choosing what to do.

For a great podcast on John Boyd, the father of the OODA loop, try this one.

And for the deepest dive on OODA (don’t start with this one) see Osinga – Science, Strategy and War.

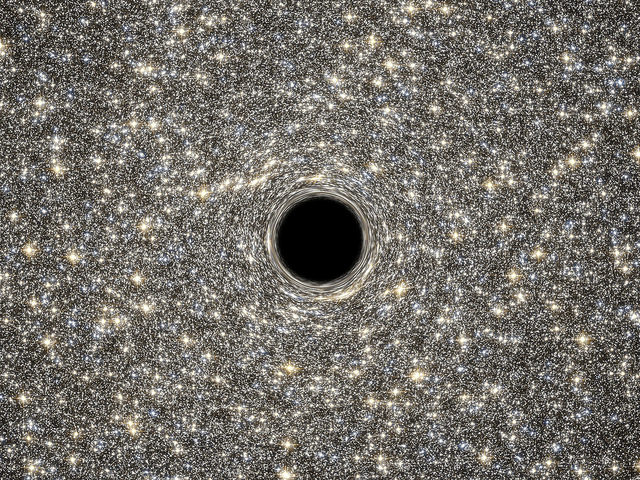

A Little Uninterrupted Work Goes a Long Way

If your day doesn’t start with a list of things you want to get done, there’s little chance you’ll get them done. What if you spent thirty minutes to define what you want to get done and then spent an hour getting them done? In ninety minutes you’ll have made a significant dent in the most important work. It doesn’t sound like a big deal, but it’s bigger than big. Question: How often do you work for thirty minutes without interruptions?

If your day doesn’t start with a list of things you want to get done, there’s little chance you’ll get them done. What if you spent thirty minutes to define what you want to get done and then spent an hour getting them done? In ninety minutes you’ll have made a significant dent in the most important work. It doesn’t sound like a big deal, but it’s bigger than big. Question: How often do you work for thirty minutes without interruptions?

Switching costs are high, but we don’t behave that way. Once interrupted, what if it takes ten minutes to get back into the groove? What if it takes fifteen minutes? What if you’re interrupted every ten or fifteen minutes? Question: What if the minimum time block to do real thinking is thirty minutes of uninterrupted time?

Let’s assume for your average week you carve out sixty minutes of uninterrupted time each day to do meaningful work, then, doing as I propose – spending thirty minutes planning and sixty minutes doing something meaningful every day – increases your meaningful work by 50%. Not bad. And if for your average week you currently spend thirty contiguous minutes each day doing deep work, the proposed ninety-minute arrangement increases your meaningful work by 200%. A big deal. And if you only work for thirty minutes three out of five days, the ninety-minute arrangement increases your meaningful work by 400%. A night and day difference.

Question: How many times per week do you spend thirty minutes of uninterrupted time working on the most important things? How would things change if every day you spent thirty minutes planning and sixty minutes doing the most important work?

Great idea, but with today’s business culture there’s no way to block out ninety minutes of uninterrupted time. To that I say, before going to work, plan for thirty minutes at home. And set up a sixty-minute recurring meeting with yourself first thing every morning and do sixty minutes of uninterrupted work. And if you can’t sit at your desk without being interrupted, hold the sixty-minute meeting with yourself in a location where you won’t be interrupted. And, to make up for the thirty minutes you spent planning at home, leave thirty minutes early.

No way. Can’t do it. Won’t work.

It will work. Here’s why. Over the course of a month, you’ll have done at least 50% more real work than everyone else. And, because your work time is uninterrupted, the quality of your work will be better than everyone else’s. And, because you spend time planning, you will work on the most important things. More deep work, higher quality working conditions, and regular planning. You can’t beat that, even if it’s only sixty to ninety minutes per day.

The math works because in our normal working mode, we don’t spend much time working in an uninterrupted way. Do the math for yourself. Sum the number of minutes per week you spend working at least thirty minutes at time. And whatever the number, figure out a way to increase the minutes by 50%. A small number of minutes will make a big difference.

Image credit – NASA Goddard Space Flight Center

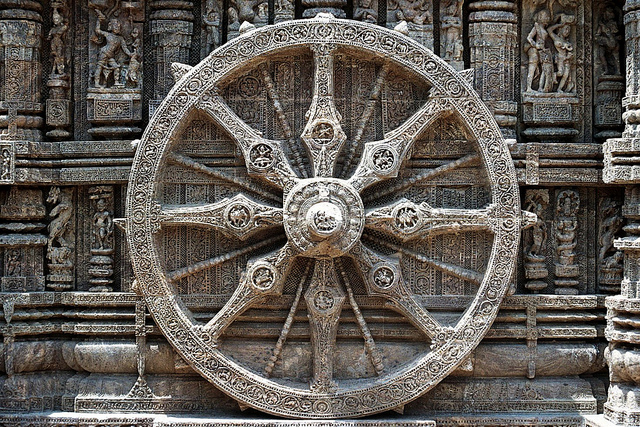

Testing the Business Model

Sometimes we get caught up in the details when we should be working on the foundation. Here’s a rule: If the underlying foundation is not secure, don’t bother working on anything else.

Sometimes we get caught up in the details when we should be working on the foundation. Here’s a rule: If the underlying foundation is not secure, don’t bother working on anything else.

If you’re working on a couple new technologies, but the overall business model won’t be profitable, don’t work on the new technologies. Instead, figure out a business model that is profitable, then do what it takes (technology, simplification, process improvement) to make it happen. But, often, that’s not what we do.

Often, we put the cart before the horse. We create projects to make prototypes that demonstrate a new technology, but the whole business premise is built on quicksand. There’s a reason why foundations are made from concrete and not quicksand. It’s because you can build on top of a base made of concrete. It supports the load. It doesn’t crack, nor does it fall apart. Think Pyramid of Giza.

Because foundations are big and expensive they can be difficult and expensive to test. For example, if an innovation is based on a new foundation, say, a new business model, building a physical prototype of the new business model is too expensive and the testing will not happen. And what usually happens is the foundation goes untested, the higher level technology work is done, the commercialization work is completed and the business model fails because it wasn’t solid.

But you don’t have to build a full-scale prototype of the Pyramid of Giza to test if a pyramid will stand the test of time. You can build a small one and test it, or you can run an analysis of some sort to understand if the pyramid will support the weight. But what if you want to test a new business model, a business model that has never been done before, using new products and services that have never seen the light of day? What do you do? In this case, it doesn’t make sense to make even a scale model. But it does make sense to create a one page sales tool that describes the whole thing and it does make sense to show it to potential customers and ask them what they think about it.

The open question with all new things is – will customers like it enough to buy it. And, it’s no different with the business model. Instead of creating a new website, staffing up, creating new technologies and products, create a one-page sales tool that describes the new elements and show it to potential customers. Distill the value proposition into language people can understand, describe the novelty that fuels the value, capture it on one page, show it to customers, and listen.

And don’t build a single, one-page sales tool, build two or three versions. And then, ask customers what they think. Odds are, they’ll ask you questions you didn’t think they’d ask. Odds are, they’ll see it differently than you do. And, odds are, you’ll have to incorporate their feedback into an improved version of the business model. The bad new is you didn’t get it right. The good news is you didn’t have to staff up and build the whole business model, create the technologies and launch the products. And more good news – you can quickly modify the one-page sales tool and go back to the customers and ask them what they think. And you can do this quickly and inexpensively.

Don’t develop the technology until you know the underlying business model will be profitable. Don’t staff up until you know if the business model holds water. Don’t launch the new products until you verify customers will buy what you want to sell.

Creating a new business model from scratch is an expensive proposition. Don’t build it until you invest in validating it’s worth building.

The worst way to validate a business model is by building it.

Image credit – David Stanley

The Slow No

When there’s too much to do and too few to do it, the natural state of the system is fuller than full. And in today’s world we run all our systems this way, including our people systems.

When there’s too much to do and too few to do it, the natural state of the system is fuller than full. And in today’s world we run all our systems this way, including our people systems.

A funny thing happens when people’s plates are full – when a new task is added an existing one hits the floor. This isn’t negligence, it’s not the result of a bad attitude and it’s not about being a team player. This is an inherent property of full plates – they cannot support a new task without another sliding off. And drinking glasses have this same interesting property – when full, adding more water just gets the floor wet.

But for some reason we think people are different. We think we can add tasks without asking about free capacity and still expect the tasks to get done. What’s even more strange – when our people tell us they cannot get the work done because they already have too much, we don’t behave like we believe them. We say things like “Can you do more things in parallel?” and “Projects have natural slow phases, maybe you can do this new project during the slow times.” Let’s be clear with each other – we’re all overloaded, there are no slow times.

For a long time now, we’ve told people we don’t want to hear no. And now, they no longer tell us. They still know they can’t get the work done, but they know not to use the word “no.” And that’s why the Slow No was invented.

The Slow No is when we put a new project on the three year road map knowing full-well we’ll never get to it. It’s not a no right now, it’s a no three years from now. It’s elegant in its simplicity. We’ll put it on the list; we’ll put it in the queue; we’ll put it on the road map. The trick is to follow normal practices to avoid raising concerns or drawing attention. The key to the Slow No is to use our existing planning mechanisms in perfectly acceptable ways.

There’s a big downside to the Slow No – it helps us think we’ve got things under control when we don’t. We see a full hopper of ideas and think our future products will have sizzle. We see a full road map and think we’re going to have a huge competitive advantage over our competitors. In both situations, we feel good and in both situations, we shouldn’t. And that’s the problem. The Slow No helps us see things as we want them and blocks us from seeing them as they are.

The Slow No is bad for business, and we should do everything we can to get rid of it. But, it’s engrained behavior and will be with us for the near future. We need some tools to battle the dark art of the Slow No.

The Slow No gives too much value to projects that are on the list but inactive. We’ve got to elevate the importance of active, fully-staffed projects and devalue all inactive projects. Think – no partial credit. If a project is active and fully-staffed, it gets full credit. If it’s inactive (on a list, in the queue, or on the road map) it gets zero credit. None. As a project, it does not exist.

To see things as they are, make a list of the active, fully-staffed projects. Look at the list and feel what you feel, but these are the only projects that matter. And for the road map, don’t bother with it. Instead, think about how to finish the projects you have. And when you finish one, start a new one.

The most difficult element of the approach is the valuation of active but partially-staffed projects. To break the vice grip of the Slow No, think no partial credit. The project is either fully-staffed or it isn’t And if it’s not fully-staffed, give the project zero value. None. I know this sounds outlandish, but the partially-staffed project is the slippery slope that gives the Slow No its power.

For every fully-staffed project on your list, define the next project you’ll start once the current one is finished. Three active projects, three next projects. That’s it. If you feel the need to create a road map, go for it. Then, for each active project, use the road map to choose the next projects. Again, three active projects, three next projects. And, once the next projects are selected, there’s no need to look at the road map until the next projects are almost complete.

The only projects that truly matter are the ones you are working on.

Image credit – DaPuglet

Being Right in the Right Way

When something doesn’t feel right, respect your intuition. Even when you don’t know why it doesn’t feel right, respect your gut. When something doesn’t make sense, don’t judge yourself negatively. Rather, make the commitment to dig deeply until you hit the fundamentals. When a proposed approach violates something inside, don’t be afraid to say what you think is right. Or, be afraid and say it anyway. But right doesn’t mean your predictions will come true. Right means you thought about it, you understand things differently and you have a coherent rationale for thinking as you do. And right also means you don’t understand, but you want to. And right means something does not sit well with you and you don’t know why. And it means the right view is important to you.

When something doesn’t feel right, respect your intuition. Even when you don’t know why it doesn’t feel right, respect your gut. When something doesn’t make sense, don’t judge yourself negatively. Rather, make the commitment to dig deeply until you hit the fundamentals. When a proposed approach violates something inside, don’t be afraid to say what you think is right. Or, be afraid and say it anyway. But right doesn’t mean your predictions will come true. Right means you thought about it, you understand things differently and you have a coherent rationale for thinking as you do. And right also means you don’t understand, but you want to. And right means something does not sit well with you and you don’t know why. And it means the right view is important to you.

Right doesn’t mean correct. And right doesn’t mean something else is wrong. When you have right view, it doesn’t mean you see things exactly right. It means you’re going about things in a way that’s right for the situation. It means your approach feels right to the people involved. It means you’re going about things with the right intention.

Now, like with any new idea, you’re obligated to formalize what you think is right and explain it to your peers. But, to be clear, you’re not looking for permission, you’re writing it down to help you understand what you think. When you try to present your thoughts, you’ll learn what you know and what you don’t. You’ll learn which words work and which don’t. You’ll learn right speech.

And you’ll find the potholes. And that’s why you present to your peers. They’ll be critical of the idea and respectful of you. They’ll tell you the truth because they know it’s better to iron out the details early and often. As a group, you’ll support each other. As a group, you’ll take the right action.

When ideas are introduced that are different, the organization will feel stress. Everyone wants to do a good job, yet there’s no agreement on the right way. Even though there’s stress, no one wants to create harm and everyone wants to behave ethically. It’s important to demonstrate compassion to yourself and others. The stress is natural, but it’s also natural to go about your livelihood in the right way.

But when the stakes are high and there’s no consensus on how to move forward, it’s not easy to hold onto the right mental state. The stress can cause us to delude ourselves into thinking things aren’t going well. But, letting the disagreement go unaddressed is unskillful, as it will only fester. It’s far more skillful to respectfully debate and discuss the disagreement. In that way, everyone makes the right effort to work things out.

Over time, the pattern of behavior can transition to a natural openness where ideas are shared freely. This becomes easier when we drop the mental habit of categorizing things into buckets we like and buckets we don’t. And it helps to maintain awareness of how things really are so we can strip away our subjective options. In this case, mindfulness is the right way to go.

None of this is easy. Our minds are constantly distracted by competing demands, growing to-do lists and organizational complexities of the work. Without dedicated practice, our minds can get lost in a flurry of thoughts of our own creation. To make it work, we’ve got to maintain a heightened alertness to our mental state and that takes the right concentration.

There’s nothing new here, but this well-worn path has merit.

Image credit – saamiblog

For top line growth, think no-to-yes.

Bottom line growth is good, but top line growth is better. But if you want to grow the bottom line, ignore labor costs and reduce material costs. Labor cost is only 5-10% of product cost. Stop chasing it, and, instead, teach your design community to simplify the product so it uses fewer parts and design out the highest cost elements.

Bottom line growth is good, but top line growth is better. But if you want to grow the bottom line, ignore labor costs and reduce material costs. Labor cost is only 5-10% of product cost. Stop chasing it, and, instead, teach your design community to simplify the product so it uses fewer parts and design out the highest cost elements.

Where the factory creates bottom line growth, top line growth is generated in the market/customer domain. The best way I know to grow the top line is to broaden the applicability of your products and services. But, before you can broaden applicability, you’ve got to define applicability as it is. Define the limits of what your product can do – how much it can lift, how fast it can run a calculation and where it can be used. And for your service, define who can use it, where it can be used and what elements without customer involvement. And with the limits defined, you know where top line growth won’t come from.

Radical top line growth comes only when your products and services can be used in new applications. Sure, you can train your sales force to sell more of what you already have, but that runs out of gas soon enough. But, real top line growth comes when your services serve new customers in new ways. By definition, if you’re not trying to make your product work in new ways, you’re not going to achieve meaningful top line growth. And by definition, if you’re not creating new functionality for your services, you might as well be focusing on bottom line growth.

If your product couldn’t do it and now it can, you’re doing it right. If your service couldn’t be used by people that speak Chinese and now it can, you’re on your way. If your product couldn’t be used in applications without electricity and now it can, you’re on to something. If your service couldn’t run on a smartphone and now it can, well, you get the idea.

For the acid test, think no-to-yes.

If your product can’t work in application A, you can’t sell it to people who do that work. If your service can’t be used by visually impaired people, you’re not delivering value to them and they won’t buy it. Turning can’t into can is a big deal. But you’ve got to define can’t before you can turn it into can. If you want top line growth, take the time to define the limits of applicability.

No-to-yes is powerful because it creates clarity. It’s easy to know when a project will create no-to-yes functionality and when it won’t. And that makes it easy to stop projects that don’t deliver no-to-yes value and start projects that do.

No-to-yes is the key element of a compete-with-no-one approach to business.

image credit – liebeslakritze

With novelty, less can be more.

When it’s time to create something new, most people try to imagine the future and then put a plan together to make it happen. There’s lots of talk about the idealize future state, cries for a clean slate design or an edict for a greenfield solution. Truth is, that’s a recipe for disaster. Truth is, there is no such thing as a clean slate or green field. And because there are an infinite number of future states, it’s highly improbable your idealized future state is the one the universe will choose to make real.

When it’s time to create something new, most people try to imagine the future and then put a plan together to make it happen. There’s lots of talk about the idealize future state, cries for a clean slate design or an edict for a greenfield solution. Truth is, that’s a recipe for disaster. Truth is, there is no such thing as a clean slate or green field. And because there are an infinite number of future states, it’s highly improbable your idealized future state is the one the universe will choose to make real.

To create something new, don’t look to the future. Instead, sit in the present and understand the system as it is. Define the major elements and what they do. Define connections among the elements. Create a functional diagram using blocks for the major elements, using a noun to name each block, and use arrows to define the interactions between the elements, using a verb to label each arrow. This sounds like a complete waste of time because it’s assumed that everyone knows how the current state system behaves. The system has been the backbone of our success, of course everyone knows the inputs, the outputs, who does what and why they do it.

I have created countless functional models of as-is systems and never has everyone agreed on how it works. More strongly, most of the time the group of experts can’t even create a complete model of the as-is system without doing some digging. And even after three iterations of the model, some think it’s complete, some think it’s incomplete and others think it’s wrong. And, sometimes, the team must run experiments to determine how things work. How can you imagine an idealized future state when you don’t understand the system as it is? The short answer – you can’t.

And once there’s a common understanding of the system as it is, if there’s a call for a clean sheet design, run away. A call for a clean sheet design is sure fire sign that company leadership doesn’t know what they’re doing. When creating something new it’s best to inject the minimum level of novelty and reuse the rest (of the system as it is). If you can get away with 1% novelty and 99% reuse, do it. Novelty, by definition, hasn’t been done before. And things that have never been done before don’t happen quickly, if they happen at all. There’s no extra credit for maximizing novelty. Think of novelty like ghost pepper sauce – a little goes a long way. If you want to know how to handle novelty, imagine a clean sheet design and do the opposite.

Greenfield designs should be avoided like the plague. The existing system has coevolved with its end users so that the system satisfies the right needs, the users know how to use the system and they know what to expect from it. In a hand-in-glove way, the as-is system is comfortable for end users because it fits them. And that’s a big deal. Any deviation from baseline design (novelty) will create discomfort and stress for end users, even if that novelty is responsible for the enhancement you’re trying to deliver. Novelty violates customer expectations and violating customer expectations is a dangerous game. Again, when you think novelty, think ghost peppers. If you want to know how to handle novelty, imagine a green field and do the opposite.

This approach is not incrementalism. Where you need novelty, inject it. And where you don’t need it, reuse. Design the system to maximize new value but do it with minimum novelty. Or, better still, offer less with far less. Think 90% of the value with 10% of the cost.

Image credit – Laurie Rantala

Thoughts on Selling

Like most things, selling is about people.

Like most things, selling is about people.

The hard sell has nothing to do with selling.

Just when you think you’re having the least influence, you’re having the most.

When – ready, sell, listen – has run its course, try – ready, listen, sell.

Regardless of how politely it’s asked, “How many do you want?” isn’t selling.

If sales people are compensated by sales dollars, why do you think they’ll sell strategically?

The time horizon for selling defines the selling.

When people think you’re selling, they’re not thinking about buying.

Selling is more about ears than mouths.

Selling on price is a race to the bottom.

Wanting sales people to develop relationships is a great idea; why not make it worth their while?

Solving customer problems is selling.

Making it easy to buy makes it easy to sell.

You can’t sell much without trust.

Sell like you expect your first sale will happen a year from now.

Selling is a result.

I’m not sure the best way to sell; but listening can’t hurt.

Over-promising isn’t selling, unless you only want to sell once.

Helping customers grow is selling.

Delaying gratification is exceptionally difficult, but it’s wonderful way to sell.

Ground yourself in the customers’ work and the selling will take care of itself.

People buy from people and people sell to people.

Image credit – Kevin Dooley

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski