Archive for the ‘Robust Economy’ Category

Resurrecting Manufacturing Through Product Simplification

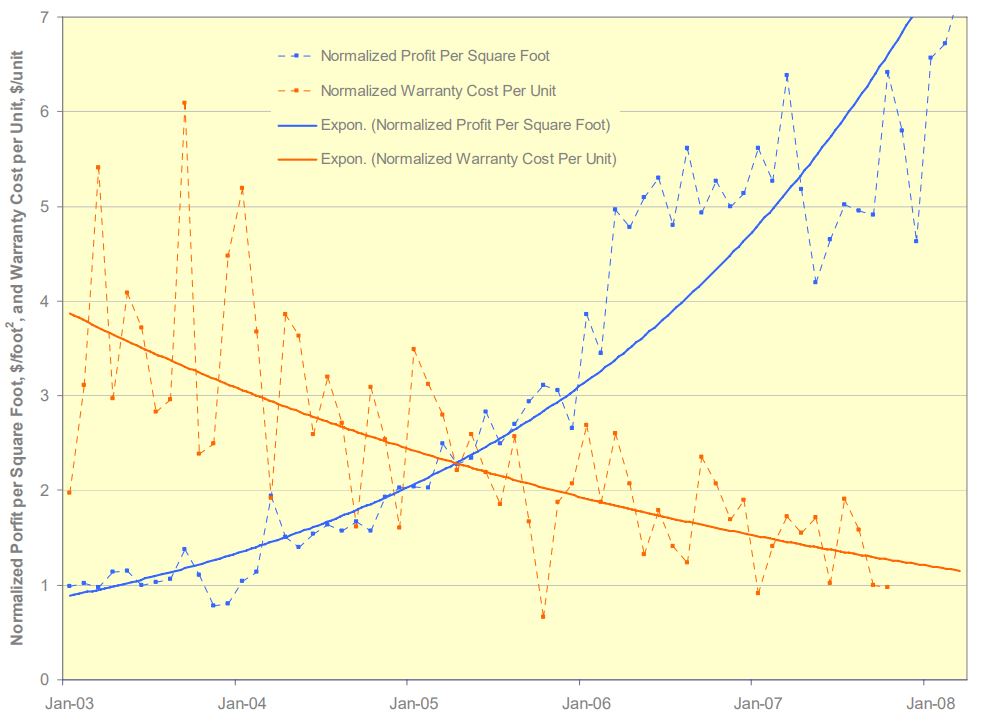

Product simplification can radically improve profits and radically improve product robustness. Here’s a graph of profit per square foot ($/ft^2) which improved by a factor of seven and warranty cost per unit ($/unit), a measure of product robustness), which improved by a factor of four. The improvements are measured against the baseline data of the legacy product which was replaced by the simplified product. Design for Assembly (DFA) was used to simplify the product and Robust Design methods were used to reduce warranty cost per unit.

I will go on record that everyone will notice when profit per square foot increases by a factor of seven.

And I will also go on record that no one will believe you when you predict product simplification will radically improve profit per square foot.

And I will go on record that when warranty cost per unit is radically reduced, customers will notice. Simply put, the product doesn’t break and your customers love it.

But here’s the rub. The graph shows data over five years, which is a long time. And if the product development takes two years, that makes seven long years. And in today’s world, seven years is at least four too many. But take another look at the graph. Profit per square foot doubled in the first two years after launch. Two years isn’t too long to double profit per square foot. I don’t know of a faster way, More strongly, I don’t know of another way to get it done, regardless of the timeline.

I think your company would love to double the profit per square foot of its assembly area. And I’ve shown you the data that proves it’s possible. So, what’s in the way of giving it a try?

For the details about the work, here’s a link – Systematic DFMA Deployment, It Could Resurrect US Manufacturing.

The Dark Underbelly of Success

Best practice – a tired recipe you recycle because you think the world is static.

Best practice – a tired recipe you recycle because you think the world is static.

Emergent practice – a new way to work created from whole cloth because the context is new.

Worst practice – a best practice applied to a world that has changed around you.

Novel practice– work that recognizes the world is a different place but is dismissed out-of-hand because everyone wants to live in the comfortable past.

Continuous improvement – when you try to put a shine on a tired, old process that worked ten years ago.

Discontinuous improvement – work that is disrespectful to the Status Quo and hurts people’s feelings.

Grow the core – when you do what you did in 2010 because you don’t know what else to do.

Obsolete your best work – when you do work that makes it clear to your customers that they should not have purchased your most successful product.

Reduce operating expense – what you do when you don’t know how to grow the top line and want to eliminate the flexibility to respond to an uncertain future.

Grow the top line – when you launch a new product that causes your customers to happily throw away the product they just bought from you.

A PowerPoint slide deck that defines your strategic plan – an electronic work product that distracts you from the reality of an ever-changing future.

A new product that is radically better than your last one – what you should create instead of a PowerPoint slide deck that defines your strategic plan.

MBA – a university degree that gives you a pedigree so companies hire you.

Ph.D. – a university degree that teaches you to learn, but takes too long.

Return On Investment (ROI) – a calculation that scuttles new work that would reinvent your business.

Imagination – thinking that will help you navigate an uncertain future, but is knee-capped by the ROI calculation.

Standard work – a process you used last time and will use next time because, again, you think the world is static.

Judgment – thinking that creates a whole new business trajectory to address an uncertain future but can get you fired if you use it.

A sustainable competitive advantage – a relic of a slow-moving world.

Continual change – the only way to deal with an ever-accelerating future.

Success – profits from work done by people who retired from your company some time ago.

Success – the thing that blocks you from working on the unproven.

Success – what pays the bills.

Success – what jeopardizes your ability to pay the bills in five years.

Success – why people think old practices are best practices.

Success – why new work is so difficult to do.

Success – why continuous improvement carries the day.

Success – why discontinuous improvement threatens.

Success – the mother of complacency.

“dark underbelly” by JoeBenjamin is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0

The Most Important People in Your Company

When the fate of your company rests on a single project, who are the three people you’d tap to drag that pivotal project over the finish line? And to sharpen it further, ask yourself “Who do I want to lead the project that will save the company?” You now have a list of the three most important people in your company. Or, if you answered the second question, you now have the name of the most important person in your company.

When the fate of your company rests on a single project, who are the three people you’d tap to drag that pivotal project over the finish line? And to sharpen it further, ask yourself “Who do I want to lead the project that will save the company?” You now have a list of the three most important people in your company. Or, if you answered the second question, you now have the name of the most important person in your company.

The most important person in your company is the person that drags the most important projects over the finish line. Full stop.

When the project is on the line, the CEO doesn’t matter; the General Manager doesn’t matter; the Business Leader doesn’t matter. The person that matters most is the Project Manager. And the second and third most important people are the two people that the Project Manager relies on.

Don’t believe that? Well, take a bite of this. If the project fails, the product doesn’t sell. And if the product doesn’t sell, the revenue doesn’t come. And if the revenue doesn’t come, it’s game over. Regardless of how hard the CEO pulls, the product doesn’t launch, the revenue doesn’t come, and the company dies. Regardless of how angry the GM gets, without a product launch, there’s no revenue, and it’s lights out. And regardless of the Business Leader’s cajoling, the project doesn’t cross the finish line unless the Project Manager makes it happen.

The CEO can’t launch the product. The GM can’t launch the product. The Business Leader can’t launch the product. Stop for a minute and let that sink in. Now, go back to those three sentences and read them out loud. No, really, read them out loud. I’ll wait.

When the wheels fall off a project, the CEO can’t put them back on. Only a special Project Manager can do that.

There are tools for project management, there are degrees in project management, and there are certifications for project management. But all that is meaningless because project management is alchemy.

Degrees don’t matter. What matters is that you’ve taken over a poorly run project, turned it on its head, and dragged it across the line. What matters is you’ve run a project that was poorly defined, poorly staffed, and poorly funded and brought it home kicking and screaming. What matters is you’ve landed a project successfully when two of three engines were on fire. (Belly landings count.) What matters is that you vehemently dismiss the continuous improvement community on the grounds there can be no best practice for a project that creates something that’s new to the world. What matters is that you can feel the critical path in your chest. What matters is that you’ve sprinted toward the scariest projects and people followed you. And what matters most is they’ll follow you again.

Project Managers have won the hearts and minds of the project team.

The Project manager knows what the team needs and provides it before the team needs it. And when an unplanned need arises, like it always does, the project manager begs, borrows, and steals to secure what the team needs. And when they can’t get what’s needed, they apologize to the team, re-plan the project, reset the completion date, and deliver the bad news to those that don’t want to hear it.

If the General Manager says the project will be done in three months and the Project Manager thinks otherwise, put your money on the Project Manager.

Project Managers aren’t at the top of the org chart, but we punch above our weight. We’ve earned the trust and respect of most everyone. We aren’t liked by everyone, but we’re trusted by all. And we’re not always understood, but everyone knows our intentions are good. And when we ask for help, people drop what they’re doing and pitch in. In fact, they line up to help. They line up because we’ve gone out of our way to help them over the last decade. And they line up to help because we’ve put it on the table.

Whether it’s IoT, Digital Strategy, Industry 4.0, top-line growth, recurring revenue, new business models, or happier customers, it’s all about the projects. None of this is possible without projects. And the keystone of successful projects? You guessed it. Project Managers.

Image credit – Bernard Spragg .NZ

Growth Isn’t The Answer

Most companies have growth objectives – make more, sell more and generate more profits. Increase profit margin, sell into new markets and twist our products into new revenue. Good news for the stock price, good news for annual raises and plenty of money to buy the things that will help us grow next year. But it’s not good for the people that do the work.

Most companies have growth objectives – make more, sell more and generate more profits. Increase profit margin, sell into new markets and twist our products into new revenue. Good news for the stock price, good news for annual raises and plenty of money to buy the things that will help us grow next year. But it’s not good for the people that do the work.

To increase sales the same sales folks will have to drive more, call more and do more demos. Ten percent more work for three percent more compensation. Who really benefits here? The worker who delivers ten percent more or the company that pays them only three percent more? Pretty clear to me it’s all about the company and not about the people.

To increase the number of units made implies that there can be no increase in the number of people required to make them. To increase throughput without increasing headcount, the production floor will have less time for lunch, less time for improving their skills and less time to go to the bathroom. Sure, they can do Lean projects to eliminate waste, as long as they don’t miss their daily quota. And sure, they can help with Six Sigma projects to reduce variation, as long as they don’t miss TAKT time. Who benefits more – the people or the company?

Increased profit margin (or profit percentage) is the worst offender. There are only two ways to improve the metric – sell it for more or make it for less. And even better than that is to sell it for more AND make it for less. No one can escape this metric. The sales team must meet with more customers; the marketing team must work doubly hard to define and communicate the value proposition; the engineering staff must reduce the time to launch the product and make it perform better than their best work; and everyone else must do more with less or face the chopping block.

In truth, corporate growth is the fundamental behind global warming, reduced life expectancy in the US and the ridiculous increase in the cost of healthcare. Growth requires more products and more products require more material mined, pumped or clear-cut from the planet. Growth puts immense pressure on the people doing the work and increases their stress level. And when they can’t deliver, their deep sense of helplessness and inadequacy causes them to kill themselves. And healthcare costs increase because the companies within (and insuring) the system need to make more profit. Who benefits here? The people in our community? The people doing the work? The planet? Or the companies?

What if we decided that companies could not grow? What if instead companies paid dividends to the people do the work based on the profit the company makes? With constant output wouldn’t everyone benefit year-on-year?

What if we decided output couldn’t grow? What if instead, as productivity increased, companies required people to work fewer hours? What if everyone could make the same number of products in seven hours and went home an hour early, working seven and getting paid for eight? Would everyone be better off? Wouldn’t the planet be better off?

What if we decided the objective of companies was to employ more people and give them a sense of purpose and give meaning to their lives? What if we used the profit created by productivity improvements to employ more people? Wouldn’t our communities benefit when more people have good jobs? Wouldn’t people be happier because they can make a contribution to their community? Wouldn’t there be less stress and fewer suicides when parents have enough money to feed their kids and buy them clothes? Wouldn’t everyone benefit? Wouldn’t the planet benefit?

Year-on-year growth is a fallacy. Year-on-year growth stresses the planet and the people doing the work. Year-on-year growth is good for no one except the companies demanding year-on-year growth.

The planet’s resources are finite; people’s ability to do work is finite; and the stress level people can tolerate is finite. Why not recognize these realities?

And why not figure out how to structure companies in a way that benefits the owners of the company, the people doing the work, the community where the work is done and the planet?

Image credit – Ryan

Growth for growth’s sake isn’t the answer

Growth, as a strategy, is flawed. Draw a control volume around the planet and accelerate the growth engines: the natural conclusion – we run out of natural resources. Not if, when. Anything with a finite end condition is finite. That’s a rule. Because the world has finite resources, growth is finite.

Growth, as a strategy, is flawed. Draw a control volume around the planet and accelerate the growth engines: the natural conclusion – we run out of natural resources. Not if, when. Anything with a finite end condition is finite. That’s a rule. Because the world has finite resources, growth is finite.

Economists say growth is the only way. And the analysts say you’ve got to grow faster than their expectations or they’ll penalize your stock price. Economists say growth must be eternal and analysists say it’s never fast enough. The treadmill of growth keeps us accelerating, and we’re moving too fast to stop and ask why.

The idea behind growth is simple – with growth comes riches. As we’ve defined the system, when companies grow the people that own stock make more money. And in with our consumption mindset, more money means more stuff. Cutting right to it, company growth breeds bank account growth, which in turn breeds four cars, a 5,000 square foot primary residence, two vacation homes, closets full of too many clothes, three iPads, six laptops and five smart phones. And from this baseline, continued growth breeds more spiraling consumption.

If the consumption was curbed, what would happen to the riches?

Growth is better when it’s a result. Solve a societal problem and growth results, but instead of just filling the coffers, peoples’ lives get better. Make the water cleaner, people get healthier and you grow. And because you see the societal benefit, you feel better about yourself and your work.

Stock price increases when analysts think growth will increase. And increased stock price creates more wealth to fund more growth and fund more consumption. And, more consumption creates the right conditions for more growth.

What would happen if there was no growth?

If we were content with what we have, flat sales wouldn’t be a problem because we’d not need to consume more. And if we didn’t need to consume more we’d be happy with the money we make. No growth would be no problem.

Today, increased productivity is used to support increased sales. The incremental capacity (more units per hour) provides more products so more can be sold which creates growth. But in a “no growth” universe where growth is prohibited, instead of selling more, people would work less. Increase productivity by 25% and instead of working five days a week, everyone works four. That’s hard to imagine, but the numbers work. Instead of more money, we’d have more time.

Money isn’t finite, but time is. If we can learn to see time as something more valuable than money, maybe things can turn around. If we can see a growth in leisure time as some twisted form of consumption, maybe that would make it okay to spend more time doing the things we want to do.

Image credit — Michael

Recalibrating Your Fear

Everyone is looking for that new thing, that differentiator, that edge. The important filtering question is: Has it been done before? If it has been done before it cannot be a new thing (that’s a rule), so it’s important to limit yourself to things that have not been done. Sounds silly to say, but with today’s hectic pace sometimes that distinction is overlooked.

Everyone is looking for that new thing, that differentiator, that edge. The important filtering question is: Has it been done before? If it has been done before it cannot be a new thing (that’s a rule), so it’s important to limit yourself to things that have not been done. Sounds silly to say, but with today’s hectic pace sometimes that distinction is overlooked.

Once your eyeballs are calibrated, it pretty easy to see the vital yet-to-be-done work. But calibration is definitely needed because things don’t look as they seem. Here are a few examples to help you calibrate.

“It can’t be done.” This really means is it was tried some time ago by someone who doesn’t work here anymore and we’ve forgotten why, but the one experiment that was run did not work. This a good indication of fertile ground. Someone a long time ago thought it was important enough to try and it still has not been done successfully. And, new materials and manufacturing processes have been created and opened up new design space. Give it a try.

“That will never work.” See above.

“You can’t do that.” This means you (and, likely your industry) have a policy that has blocks this new idea. It may not be the best idea, but since policy prohibits it, you have the design space all to yourself if you want it. (That is, of course, if you want to compete with no one.) Likely there are no physical constraints, just the emotional constraints you created with your policy. It’s all yours, if you try it.

“No one will buy that.” This means no one offers a product like that. It means your industry doesn’t understand it because you or your competitors don’t sell anything like it. Though Marketing knows the inherent uncertainty, they don’t know the market potential. But you know you’re onto something. Try it.

“That’s just a niche market.” This means there’s a market that’s buying your product even though you’ve spent no time or energy to develop that market. It’s an accidental market. It’s small because it’s young and because you (and your competition) haven’t invested in it nor have developed an unique new product for it. The growth is all yours if you try.

Organizations create blocking mechanisms and tricky language to protect themselves from the new-and-different because the new-and-different are scary. But organizations desperately need new-and-different. And for that they desperately need to do things that haven’t been done.

The first step is to recognize the fertile design space and untilled markets your fear has created for you.

Image credit — Jordan Oram

Innovation’s Mantra – Sell New Products To New Customers

There are three types of innovation: innovation that creates jobs, innovation that’s job neutral, and innovation that reduces jobs.

There are three types of innovation: innovation that creates jobs, innovation that’s job neutral, and innovation that reduces jobs.

Innovation that reduces jobs is by far the most common. This innovation improves the efficiency of things that already exist – the mantra: do the same, but with less. No increase in sales, just fewer people employed.

Innovation that’s job neutral is less common. This innovation improves what you sell today so the customer will buy the new one instead of the old one. It’s a trade – instead of buying the old one they buy the new one. No increase in sales, same number of people employed.

Innovation that creates jobs is uncommon. This innovation radically changes what you sell today and moves it from expensive and complicated to affordable and accessible. Sell more, employ more.

Clay Christensen calls it Disruptive Innovation; Vijay Govindarajan calls it Reverse Innovation; and I call it Less-With-Far-Less.

The idea is the product that is sold to a relatively small customer base (due to its cost) is transformed into something new with far broader applicability (due to its hyper-low cost). Clay says to “look down” to see the new technologies that do less but have a super low cost structure which reduces the barrier to entry. And because more people can afford it, more people buy it. And these aren’t the folks that buy your existing products. They’re new customers.

Vijay says growth over the next decades will come from the developing world who today cannot afford the developed world’s product. But, when the price comes down (down by a factor of 10 then down by a factor of 100), you sell many more. And these folks, too, are new customers.

I say the design and marketing communities must get over their unnatural fascination with “more” thinking. To sell to new customers the best strategy is increase the number of people who can afford your product. And the best way to do that is to radically reduce the cost signature at the expense of features and function. If you can give ground a bit on the thing that makes your product successful, there is huge opportunity to reduce cost – think 80% less cost and 20% less function. Again, you sell new product to new customers.

Here’s a thought experiment to help put you in the right mental context: Create a plan to form a new business unit that cannot sell to your existing customers, must sell a product that does less (20%) and costs far less (80%), and must sell it in the developing world. Now, create a list of small projects to test new technologies with radically lower cost structures, likely from other industries. The constraint on the projects – you must be able to squeeze them into your existing workload and get them done with your existing budget and people. It doesn’t matter how long the projects take, but the investment must be below the radar.

The funny thing is, if you actually run a couple small projects (or even just one) to identify those new technologies, for short money you’ve started your journey to selling new products to new customers.

Define To Solve

Countries want their companies to create wealth and jobs, and to do it they want them to design products, make those products within their borders, and sell the products for more than the cost to make them. It’s a simple and sustainable recipe which makes for a highly competitive landscape, and it’s this competition that fuels innovation.

Countries want their companies to create wealth and jobs, and to do it they want them to design products, make those products within their borders, and sell the products for more than the cost to make them. It’s a simple and sustainable recipe which makes for a highly competitive landscape, and it’s this competition that fuels innovation.

When companies do innovation they convert ideas into products which they make (jobs) and sell (wealth). But for innovation, not any old idea will do; innovation is about ideas that create novel and useful functionality. And standing squarely between ideas and commercialization are tough problems that must be solved. Solve them and products do new things (or do them better), become smaller, lighter, or faster, and people buy them (wealth).

But here’s the part to remember – problems are the precursor to innovation.

Before there can be an innovation you must have a problem. Before you develop new materials, you must have problems with your existing ones; before your new products do things better, you must have a problem with today’s; before your products are miniaturized, your existing ones must be too big. But problems aren’t acknowledged for their high station.

There are problems with problems – there’s an atmosphere of negativity around them, and you don’t like to admit you have them. And there’s power in problems – implicit in them are the need for change and consequence for inaction. But problems can be more powerful if you link them tightly and explicitly to innovation. If you do, problem solving becomes a far more popular sport, which, in turn, improves your problem solving ability.

But the best thing you can do to improve your problem solving is to spend more time doing problem definition. But for innovation not any old problem definition will. Innovation requires level 5 problem definition where you take the time to define problems narrowly and deeply, to define them between just two things, to define when and where problems occur, to define them with sketches and cartoons to eliminate words, and to dig for physical mechanisms.

With the deep dive of level 5 you avoid digging in the wrong dirt and solving the wrong problem because it pinpoints the problem in space and time and explicitly calls out its mechanism. Level 5 problem definition doesn’t define the problem, it defines the solution.

It’s not glamorous, it’s not popular, and it’s difficult, but this deep, mechanism-based problem definition, where the problem is confined tightly in space and time, is the most important thing you can do to improve innovation.

With level 5 problem definition you can transform your company’s profitability and your country’s economy. It does not get any more relevant than that.

Circle of Life

Engineers solve technical problems so

Other engineers can create products so

Companies can manufacture them so

They can sell them for a profit and

Use the wealth to pay workers so

Workers can support their families and pay taxes so

Their countries have wealth for good schools to

Grow the next generation of engineers to

Solve the next generation of technical problems so…

You might be a superhero if…

- Using just dirt, rocks, and sticks, you can bring to life a product that makes life better for society.

- Using just your mind, you can radically simplify the factory by changing the product itself.

- Using your analytical skills, you can increase product function in ways that reinvent your industry.

- Using your knowledge of physics, you can solve a longstanding manufacturing problem by making a product insensitive to variation.

- Using your knowledge of Design for Manufacturing and Assembly, you can reduce product cost by 50%.

- Using your knowledge of materials, you can eliminate a fundamental factory bottleneck by changing what the product is made from.

- Using your curiosity and creativity, you can invent and commercialize a product that creates a new industry.

- Using your superpowers, you think you can fix a country’s economy one company at a time.

Fix The Economy – Connect The Engineer To The Factory

Rumor has it, manufacturing is back. Yes, manufacturing jobs are coming back, but they’re coming back in dribbles. (They left in a geyser, so we still have much to do.) What we need is a fire hose of new manufacturing jobs.

Rumor has it, manufacturing is back. Yes, manufacturing jobs are coming back, but they’re coming back in dribbles. (They left in a geyser, so we still have much to do.) What we need is a fire hose of new manufacturing jobs.

Manufacturing jobs are trickling back from low cost countries because companies now realize the promised labor savings are not there and neither is product quality. But a trickle isn’t good enough; we need to turn the tide; we need the Mississippi river.

For flow like that we need a fundamental change. We need labor costs so low our focus becomes good quality; labor costs so low our focus becomes speed to market; labor costs so low our focus becomes speed to customer. But the secret is not labor rate. In fact, the secret isn’t even in the factory.

The secret is a secret because we’ve mistakenly mapped manufacturing solely to making (to factories). We’ve forgotten manufacturing is about designing and making. And that’s the secret: designing – adding product thinking to the mix. Design out the labor.

There are many names for designing and making done together. Most commonly it’s called concurrent engineering. Though seemingly innocuous, taken together, those words have over a thousand meanings layered with even more nuances. (Ask someone for a simple description of concurrent engineering. You’ll see.) It’s time to take a step back and demystify designing and making done together. We can do this with two simple questions:

- What behavior do we want?

- How do we get it?

What’s the behavior we want? We want design engineers to understand what drives cost in the factory (and suppliers’ factories) and design out cost. In short, we want to connect the engineer to the factory.

Great idea. But what if the factory and engineer are separated by geography? How do we get the behavior we want? We need to create a stand-in for the factory, a factory surrogate, and connect the engineer to the surrogate. And that surrogate is cost. (Cost is realized in the factory.) We get the desired behavior when we connect the engineer to cost.

When we make engineering responsible for cost (connect them to cost), they must figure out where the cost is so they can design it out. And when they figure out where the cost is, they’re effectively connected to the factory.

But the engineers don’t need to understand the whole factory (or supply chain), they only need to understand places that create cost (where the cost is.) To understand where cost is, they must look to the baseline product – the one you’re making today. To help them understand supply chain costs, ask for a Pareto chart of cost by part number for purchased parts. (The engineers will use cost to connect to suppliers’ factories.) The new design will focus on the big bars on the left of the Pareto – where the supply chain cost is.

To help them understand your factory’s cost, they must make two more Paretos. The first one is a Pareto of part count by major subassembly. Factory costs are high where the parts are – time to put them together. The second is a Pareto chart of process times. Factory costs are high where the time is – machine capacity, machine operators, and floor space.

To make it stick, use design reviews. At the first design review – where their design approach is defined – ask engineering for the three Paretos for the baseline product. Use the Pareto data to set a cost reduction goal of 50% (It will be easily achieved, but not easily believed.) and part count reduction goal of 50%. (Easily achieved.) Here’s a hint for the design review – their design approach should be strongly shaped by the Paretos.

Going forward, at every design review, ask engineering to present the three Paretos (for the new design) and cost and part count data (for the new design.) Engineering must present the data themselves; otherwise they’ll disconnect themselves from the factory.

To seal the deal, just before full production, engineering should present the go-to-production Paretos, cost, and part count data.

What I’ve described may not be concurrent engineering, but it’s the most profitable activity you’ll ever do. And, as a nice side benefit, you’ll help turn around the economy one company at a time.

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski