Archive for the ‘Product Development’ Category

Define To Solve

Countries want their companies to create wealth and jobs, and to do it they want them to design products, make those products within their borders, and sell the products for more than the cost to make them. It’s a simple and sustainable recipe which makes for a highly competitive landscape, and it’s this competition that fuels innovation.

Countries want their companies to create wealth and jobs, and to do it they want them to design products, make those products within their borders, and sell the products for more than the cost to make them. It’s a simple and sustainable recipe which makes for a highly competitive landscape, and it’s this competition that fuels innovation.

When companies do innovation they convert ideas into products which they make (jobs) and sell (wealth). But for innovation, not any old idea will do; innovation is about ideas that create novel and useful functionality. And standing squarely between ideas and commercialization are tough problems that must be solved. Solve them and products do new things (or do them better), become smaller, lighter, or faster, and people buy them (wealth).

But here’s the part to remember – problems are the precursor to innovation.

Before there can be an innovation you must have a problem. Before you develop new materials, you must have problems with your existing ones; before your new products do things better, you must have a problem with today’s; before your products are miniaturized, your existing ones must be too big. But problems aren’t acknowledged for their high station.

There are problems with problems – there’s an atmosphere of negativity around them, and you don’t like to admit you have them. And there’s power in problems – implicit in them are the need for change and consequence for inaction. But problems can be more powerful if you link them tightly and explicitly to innovation. If you do, problem solving becomes a far more popular sport, which, in turn, improves your problem solving ability.

But the best thing you can do to improve your problem solving is to spend more time doing problem definition. But for innovation not any old problem definition will. Innovation requires level 5 problem definition where you take the time to define problems narrowly and deeply, to define them between just two things, to define when and where problems occur, to define them with sketches and cartoons to eliminate words, and to dig for physical mechanisms.

With the deep dive of level 5 you avoid digging in the wrong dirt and solving the wrong problem because it pinpoints the problem in space and time and explicitly calls out its mechanism. Level 5 problem definition doesn’t define the problem, it defines the solution.

It’s not glamorous, it’s not popular, and it’s difficult, but this deep, mechanism-based problem definition, where the problem is confined tightly in space and time, is the most important thing you can do to improve innovation.

With level 5 problem definition you can transform your company’s profitability and your country’s economy. It does not get any more relevant than that.

It’s All Connected

There’s a natural tendency to simplify, to reduce, to narrow. In the name of problem solving, it’s narrow the scope, break it into small bites, and don’t worry about the subtle complexities. And for a lot of situations that works. But after years of fixing things one bite at a time, there are fewer and fewer situations that fit the divide and conquer approach. (Actually, they’re still there, but their return on investment is super low.) And after years of serial discretization, what are left are situations that cannot be broken up, that cut across interfaces, that make up a continuum. What are left are big problems and big situations that have huge payoff if solved, but are interconnected.

There’s a natural tendency to simplify, to reduce, to narrow. In the name of problem solving, it’s narrow the scope, break it into small bites, and don’t worry about the subtle complexities. And for a lot of situations that works. But after years of fixing things one bite at a time, there are fewer and fewer situations that fit the divide and conquer approach. (Actually, they’re still there, but their return on investment is super low.) And after years of serial discretization, what are left are situations that cannot be broken up, that cut across interfaces, that make up a continuum. What are left are big problems and big situations that have huge payoff if solved, but are interconnected.

Whether it’s cross-discipline, cross-organization, cross-cultural, or cross-best practice, the fundamental of these big kahunas is they cross interfaces. And that’s why they’ve never been attacked, and that’s why they’ve never been solved. But with payoffs so big, it’s time to take on connectedness.

For me, the most severe example of connectedness is woven around the product. To commercialize a product there are countless business process that cut across almost every interface. Here are a few: innovation, technology development, product development, robustness testing, product documentation, manufacturing engineering, marketing, sales, and service. Each of these processes is led by one organization and cuts across many; each cut across expertise-specialization interfaces; each requires information and knowledge from the other; and each new product development project must cooperate with all the others. They cannot be separated or broken into bits. Change one with intent and change the others with unintended consequences. No doubt – they’re connected.

Green thinking is much overdue, but with it comes connectedness squared. With pre-green product commercialization, the product flowed to the end user and that was about it. But with environmental movement there’s a whole new return path of interconnected business processes. Green thinking has turned the product life cycle into the circle of life – the product leaves, it lives it’s life, and it always comes back home.

And with this return path of connectedness, how the product goes together in manufacturing must be defined in conjunction with how it will be disassembled and recycled. Stress analysis must be coordinated with packaging design, regulations of banned substances, and material reuse of retired product. Marketing literature must be co-produced with regulatory strategy and recycling technologies. It’s connected more than ever.

But the bad news is the good news. Yes, things are more interwoven and the spider web is more tangled. But the upside – companies that can manage the complexity will have a significant advantage. Those that can navigate within connectedness will win.

The first step is to admit there’s a problem, and before connectedness can be managed, it must be recognized. And before it can become competitive advantage, it must be embraced.

Product Thinking

Product costs, without product thinking, drop 2% per year. With product thinking, product costs fall by 50%, and while your competitors’ profit margins drift downward, yours are too high to track by conventional methods. And your company is known for unending increases in stock price and long term investment in all the things that secure the future.

The supply chain, without product thinking, improves 3% per year. With product thinking, longest lead processes are eliminated, poorest yield processes are a thing of the past, problem suppliers are gone, and your distributers associate your brand with uninterrupted supply and on time delivery.

Product robustness, without product thinking, is the same year-on-year. Re-injecting long forgotten product thinking to simplify the product, product robustness jumps to unattainable levels and warranty costs plummet. And your brand is known for products that simply don’t break.

Rolled throughput yield is stalled at 90%. With product thinking, the product is simplified, opportunities for defects are reduced, and throughput skyrockets due to improved RTY. And your brand is known as a good value – providing good, repeatable functionality at a good price.

Lean, without product thinking has delivered wonderful results, but the low hanging fruit is gone and lean is moving into the back office. With product thinking, the design is changed and value-added work is eliminated along with its associated non-value added work (which is about 8 times bigger); manufacturing monuments with their long changeover times are ripped out and sold to your competitors; work from two factories is consolidated into one; new work is taken on to fill the emptied factories; and profit per square foot triples. And your brand is known for best-in-class quality, unbeatable on time delivery, world class performance, and pioneering the next generation of lean.

The sales argument is low price and good payment terms. With product thinking, the argument starts with product performance and ends with product reliability. The sales team is energized, and your brand is linked with solid products that just plain work.

The marketing approach is stickers and new packaging. With product thinking, it’s based on competitive advantage explained in terms of head-to-head performance data and a richer feature set. And your brand stands for winning technology and killer products.

Product thinking isn’t for everyone. But for those that try – your brand will thank you.

Engineering Will Carry the Day

Engineering is more important than manufacturing – without engineering there is nothing to make, and engineering is more important than marketing – without it there is nothing to market.

Engineering is more important than manufacturing – without engineering there is nothing to make, and engineering is more important than marketing – without it there is nothing to market.

If I could choose my competitive advantage, it would be an unreasonably strong engineering team.

Ideas have no value unless they’re morphed into winning products, and that’s what engineering does. Technology has no value unless it’s twisted into killer products. Guess who does that?

We have fully built out methodologies for marketing, finance, and general management, each with all the necessary logic and matching toolsets, and manufacturing has lean. But there is no such thing for engineering. Stress analysis or thermal modeling? Built a prototype or do more thinking? Plastic or aluminum? Use an existing technology or invent a new one? What new technology should be invented? Launch the new product as it stands or improve product robustness? How is product robustness improved? Will the new product meet the specification? How will you know? Will it hit the cost target? Will it be manufacturable? Good luck scripting all that.

A comprehensive, step-by-step program for engineering is not possible.

Lean says process drives process, but that’s not right. The product dictates to the factory, and engineers dictate the product. The factory looks as it does because the product demands it, and the product looks as it does because engineers said so.

I’d rather have a product that is difficult to make but works great rather than one that jumps together but works poorly.

And what of innovation? The rhetoric says everyone innovates, but that’s just a nice story that helps everyone feel good. Some innovations are more equal than others. The most important innovations create the killer products, and the most important innovators are the ones that create them – the engineers.

Engineering as a cost center is a race to the bottom; engineering as a market creator will set you free.

The only question: How are you going to create a magical engineering team that changes the game?

Engineering Incantations

Know what’s new in the new design. To do that, ask for a reuse analysis and divvy up newness into three buckets – new to your company, new to your industry, new to world. If the buckets are too big, jettison some newness, and if there’s something in the new-to-world bucket, be careful.

Know what’s new in the new design. To do that, ask for a reuse analysis and divvy up newness into three buckets – new to your company, new to your industry, new to world. If the buckets are too big, jettison some newness, and if there’s something in the new-to-world bucket, be careful.

Create test protocols (how you’ll test) and minimum acceptance criteria (specification limits) before doing design work. It’s a great way to create clarity.

Build first – build the crudest possible prototype to expose the unfamiliar, and use the learning to shape the next prototypes and to focus analyses. Do this until you run out of time.

Cost and function are joined at the hip, so measure engineering on both.

Have a healthy dissatisfaction for success. Recognize success, yes, but also recognize it’s fleeting. Someone will obsolete your success, and it should be you.

To get an engineering team to believe in themselves, you must believe in them. To believe in them, you must believe in yourself.

Untapped Power of Self

As a subject matter expert (SME), you have more power than you think, and certainly more than you demonstrate.

As a subject matter expert (SME), you have more power than you think, and certainly more than you demonstrate.

As an SME, you have special knowledge. Looking back, you know what worked, what didn’t, and why; looking forward, you know what should work, what shouldn’t, and why. There’s power in your special knowledge, but you underestimate it and don’t use it to move the needle.

As an SME, without your special knowledge there are no new products, no new technologies, and no new markets. Without it, it’s same-old, same-old until the competition outguns you. It’s time you realize your importance and behave that way.

As an SME, when you and your SME friends gang together, your company must listen. Your gang knows it all. From the system-level stuff to the most detailed detail, you know it. Remember, you invented the technology that powers your products. It’s time you behave that way.

As an SME, with your power comes responsibility – you have an obligation to use your power for good. Figure out what the technology wants, and do that; do the sustainable thing; do the thing that creates jobs; do what’s good for the economy; sit yourself in the future, look back, and do what you think is right.

As an SME, I’m calling you out. I trust you, now it’s time to trust yourself. And it’s time for you to behave that way.

Heroes of the Company

If I was a company, the first thing I’d do is invest in my engineering teams. But not for the reasons we normally associate with engineering. Not for more function and features, not for product robustness, not technology, and not patents. I would invest in engineering for increased profits.

If I was a company, the first thing I’d do is invest in my engineering teams. But not for the reasons we normally associate with engineering. Not for more function and features, not for product robustness, not technology, and not patents. I would invest in engineering for increased profits.

When it comes to their engineering divisions, other companies think minimization – fewest heads, lowest wages, least expensive tools. Not me. I’m all about maximization – smartest, best trained, and the best tools. That’s how I like to maximize profits. To me, investing in my engineering teams gives me the highest return on my investment.

Engineers create the products I sell to my customers. I’ve found when my best engineers sit down and think for a while they come up with magical ideas that translate into super-performing products, products with features that differentiate me from my cousin companies, and products that flat-out don’t break. My sales teams love to sell them (Sure, I pay a lot in bonuses, but it’s worth it.), my marketing teams love to market them, and my factory folks build them with a smile.

Over my life I’ve developed some simple truisms that I live by: When I sell more products, I make more profits; when my products allow a differentiated marketing message, I sell more and make more profits; and when my product jumps together, my quality is better, and, you guessed it, I make more profits. All these are good reasons to invest in engineering, but it’s not my reason. All this increased sales stuff is good, but it’s not great. It’s not my real reason to invest in engineering. It’s not my secret.

When I was younger I vowed to take my secret to the grave, but now that I’ve matured (and filled up several banks with money), I think it’s okay to share it. So, here goes.

My real reason to invest in engineering is material cost reduction. Yes, material cost reduction. My materials budget is one of my largest line items and I help my engineers reduce it with reckless abandon (and the right tools, time, training, and teacher.) I’ve asked my lean folks to reduce material cost, but they’ve not been able to dent it. Sure, they’ve done a super job with inventory reduction (I get a one-time carrying cost reduction.), but no material cost reduction from my lean projects. I’ve also asked my six sigma organization to reduce material costs, but they, too, have not made a dent. They’ve improved my product quality, but that doesn’t translate into piles of money like material cost reduction.

Now, I know what you’re thinking: Why, Mrs. Company, are you wasting engineering’s time with cost? Cost is manufacturing’s responsibility – they should reduce it, not engineering. Plain and simple – that’s not what I believe, and neither do my engineers. They know they create cost to enable function, good material cost – worth every penny. But they also know all other cost is bad. And since they know they design in cost, they know they’re the ones that must design it out. And they’re good at it. With the right tools, time, and training, they typically reduce material costs by 50%. Do the math –material cost for your highest volume product times 50% – year-on-year. Piles of money.

I’ve learned over the years increasing sales is difficult and takes a lot of work. I’ve also learned I can make lots of money reducing material costs without increasing sales. In fact, even during the recent downturn, through my material cost reductions I made more money than ever. I have my design engineers to thank for that.

Company-to-company, I know things have been tough for us over the last years, and money is still tight. But if you have a little extra stashed away, I urge you to invest in your engineering organization. It makes for great profits.

Seeing Things As They Are

It’s tough out there. Last year we threw the kitchen sink at our processes and improved them, and now last year’s improvements are this year’s baseline. And, more significantly, competition has increased exponentially – there are more eager countries at the manufacturing party. More countries have learned that manufacturing jobs are the bedrock of sustainable economy. They’ve designed country-level strategies and multi-decade investment plans (education, infrastructure, and energy technologies) to go after manufacturing jobs as if their survival depended on them. And they’re not just making, they’re designing and making. Country-level strategies and investments, designing and making, and citizens with immense determination to raise their standard of living – a deadly cocktail. (Have you seen Hyundai’s cars lately?)

It’s tough out there. Last year we threw the kitchen sink at our processes and improved them, and now last year’s improvements are this year’s baseline. And, more significantly, competition has increased exponentially – there are more eager countries at the manufacturing party. More countries have learned that manufacturing jobs are the bedrock of sustainable economy. They’ve designed country-level strategies and multi-decade investment plans (education, infrastructure, and energy technologies) to go after manufacturing jobs as if their survival depended on them. And they’re not just making, they’re designing and making. Country-level strategies and investments, designing and making, and citizens with immense determination to raise their standard of living – a deadly cocktail. (Have you seen Hyundai’s cars lately?)

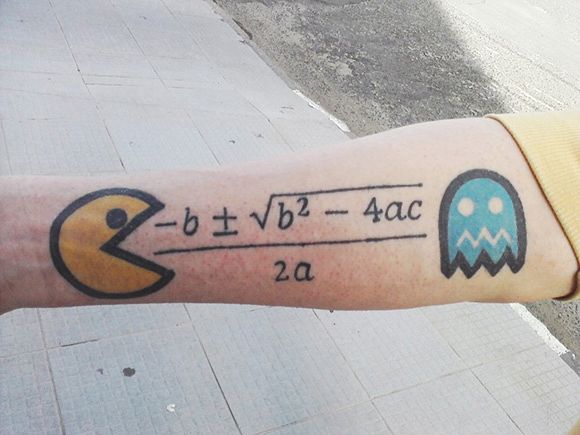

With the wicked couple of competition and profitability goals, we’re under a lot of pressure. And with the pressure comes the danger of seeing things how we want them instead of how they are, like a self-created optical illusion. Here are some likely optical illusion A-B pairs (A – how we want things; B – how they are):

A. Give people more work and more gets done. B. Human output has a physical limit, and once reached less gets done – and spouses get angry. A. Do more projects in parallel to generate more profit. B. Business processes have physical limits, and once reached projects slow and everyone works harder for the same output. A. Add resources to the core project team and more projects get done. B. Add resources to core projects teams and utilization skyrockets for shared resources – waiting time increases for all. A. Use lean in product development (just like in manufacturing) to launch new products better and faster. B. Lean done in product development is absolutely different than in manufacturing, and design engineers don’t take kindly to manufacturing folks telling them how to do their work. A. Through negotiation and price reduction, suppliers can deliver cost reductions year-on-year. B. The profit equation has a physical limit (no profit), and once reached there is no supplier. A. Use lean to reduce product cost by 5%. B. Use DFMA to reduce product cost by 50%.Competition is severe and the pressure is real. And so is the danger to see things as we want them to be. But there’s a simple way to see things as they are: ask the people that do the work. Go to the work and ask the experts. They do the work day-in-day-out, and they know what really happens. They know the details, the pinch points, and the critical interactions.

To see things as they are, check your ego at the door, and go ask the experts – the people that do the work.

How To Create a Sea of Manufacturing Jobs

It’s been a long slide from greatness for US manufacturing. It’s been downhill since the 70s – a multi-decade slide. Lately there’s a lot of hype about a manufacturing renaissance in the US – re-shoring, on-shoring, right-shoring. But the celebration misguided. A real, sustainable return to greatness will take decades, decades of single-minded focus, coordination, alignment and hard work – industry, government, and academia in it together for the long haul.

It’s been a long slide from greatness for US manufacturing. It’s been downhill since the 70s – a multi-decade slide. Lately there’s a lot of hype about a manufacturing renaissance in the US – re-shoring, on-shoring, right-shoring. But the celebration misguided. A real, sustainable return to greatness will take decades, decades of single-minded focus, coordination, alignment and hard work – industry, government, and academia in it together for the long haul.

To return to greatness, the number of new manufacturing jobs to be created is distressing. 100,000 new manufacturing jobs is paltry. And today there is a severe skills gap. Today there are unfilled manufacturing jobs because there’s no one to do the work. No one has the skills. With so many without jobs it sad. No, it’s a shame. And the manufacturing talent pipeline is dry – priming before filling. Creating a sea of new manufacturing jobs will be hard, but filling them will be harder. What can we do?

The first thing to do is make list of all the open manufacturing jobs and categorize them. Sort them by themes: by discipline, skills, experience, tools. Use the themes to create training programs, train people, and fill the open jobs. (Demonstrate coordinated work of government, industry, and academia.) Then, using the learning, repeat. Define themes of open manufacturing jobs, create training programs, train, and fill the jobs. After doing this several times there will be sufficient knowledge to predict needed skills and proactive training can begin. This cycle should continue for decades.

Now the tough parts – transcending our short time horizon and finding the money. Our time horizon is limited to the presidential election cycle – four years, but the manufacturing rebirth will take decades. Our four year time horizon prevents success. There needs to be a guiding force that maintains consistency of purpose – manufacturing resurgence – a consistency of purpose for decades. And the resurgence cannot require additional money. (There isn’t any.) So who has a long time horizon and money?

The DoD has both – the long term view (the military is not elected or appointed) and the money. (They buy a lot of stuff.) Before you call me a war hawk, this is simply a marriage of convenience. I wish there was, but there is no better option.

The DoD should pull together their biggest contractors (industry) and decree that the stuff they buy will have radically reduced cost signatures and teach them and their sub-tier folks how to get it done. No cost reduction, no contract. (There’s no reason military stuff should cost what it does, other than the DoD contractors don’t know how design things cost effectively.) The DoD should educate their contractors how to design products to reduce material cost, assembly time, supply chain complexity, and time to market and demand the suppliers. Then, demand they demonstrate the learning by designing the next generation stuff. (We mistakenly limit manufacturing to making, when, in fact, radical improvement is realized when we see manufacturing as designing and making.)

The DoD should increase its applied research at the expense of its basic research. They should fund applied research that solves real problems that result in reduced cost signatures, reduce total cost of ownership, and improved performance. Likely, they should fund technologies to improve engineering tools, technologies that make themselves energy independent and new materials. Once used in production-grade systems, the new technologies will spill into non-DoD world (broad industry application) and create new generation products and a sea of manufacturing jobs.

I think this is approach has a balanced time horizon – fill manufacturing jobs now and do the long term work to create millions of manufacturing jobs in the future.

Yes, the DoD is at the center of the approach. Yes, some have a problem with that. Yes, it’s a marriage of convenience. Yes, it requires coordination among DoD, industry, and academia. Yes, that’s almost impossible to imagine. Yes, it requires consistency of purpose over decades. And, yes, it’s the best way I know.

What is Design for Manufacturing and Assembly?

Design for Manufacturing (DFM) is all about reducing the cost of piece-parts. Design for Assembly is all about reducing the cost of putting things together (assembly). What’s often forgotten is that function comes first. Change the design to reduce part cost, but make sure the product functions well. Change the parts (eliminate them) to reduce assembly cost, but make sure the product functions well.

Paradoxically, DFM and DFA are all about function.

Here’s a link to a short video that explains DFM and DFA: link to video. (and embedded below)

Organizationally Challenged – Engineering and Manufacturing

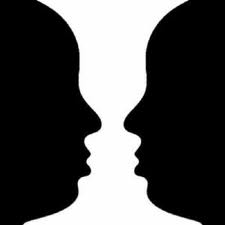

Our organizations are set up in silos, and we’re measured that way. (And we wonder why we get local optimization.) At the top of engineering is the VP of the Red Team, who is judged on what it does – product. At the top of manufacturing is the VP of the Blue Team, who is judged on how to make it – process. Red is optimized within Red and same for Blue, sometimes with competing metrics. What we need is Purple behavior.

Here’s a link to a short video (1:14): Organizationally Challenged

And embedded below:

Let me know what you think.

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski