Archive for the ‘Product Development’ Category

How To Make Progress

Improvement is progress. Improvement is always measured against a baseline, so the first thing to do is to establish the baseline, the thing you make today, the thing you want to improve. Create an environment to test what you make today, create the test fixtures, define the inputs, create the measurement systems, and write a formal test protocol. Now you have what it takes to quantify an improvement objectively. Test the existing product to define the baseline. No, you haven’t improved anything, but you’ve done the right first thing.

Improvement is progress. Improvement is always measured against a baseline, so the first thing to do is to establish the baseline, the thing you make today, the thing you want to improve. Create an environment to test what you make today, create the test fixtures, define the inputs, create the measurement systems, and write a formal test protocol. Now you have what it takes to quantify an improvement objectively. Test the existing product to define the baseline. No, you haven’t improved anything, but you’ve done the right first thing.

Improving the right thing to make progress. If the problem invalidates the business model, stop what you’re doing and solve it right away because you don’t have a business if you don’t solve it. Any other activity isn’t progress, it’s dilution. Say no to everything else and solve it. This is how rapid progress is made. If the customer won’t buy the product if the problem isn’t solved, solve it. Don’t argue about priorities, don’t use shared resources, don’t try to be efficient. Be effective. Do one thing. Solve it. This type of discipline reduces time to market. No surprises here.

Avoiding improvement of the wrong thing to make progress. For lesser problems, declare them nuisances and permit yourself to solve them later. Nuisances don’t have to be solved immediately (if at all) so you can double down on the most important problems (speed, speed, speed). Demoting problems to nuisances is probably the most effective way to accelerate progress. Deciding what you won’t do frees up resources and emotional bandwidth to make rapid progress on things that matter.

Work the critical path to make progress. Know what work is on the critical path and what is not. For work on the critical path, add resources. Pull resources from non-critical path work and add them to the critical path until adding more slows things down.

Eliminate waiting to make progress. There can be no progress while you wait. Wait for a tool, no progress. Wait for a part from a supplier, no progress. Wait for raw material, no progress. Wait for a shared resource, no progress. Buy the right tools and keep them at the workstations to make progress. Pay the supplier for priority service levels to make progress. Buy inventory of raw materials to make progress. Ensure shared resources are wildly underutilized so they’re available to make progress whenever you need to. Think fire stations, fire trucks, and firefighters.

Help the team make progress. As a leader, jump right in and help the team know what progress looks like. Praise the crudeness of their prototypes to help them make them cruder (and faster) next time. Give them permission to make assumptions and use their judgment because that’s where speed comes from. And when you see “activity” call it by name so they can recognize it for themselves, and teach them how to turn their effort into progress.

Be relentless and respectful to make progress. Apply constant pressure, but make it sustainable and fun.

Image credit — Clint Mason

Top Blog Posts of 2024

Here are the top four blog posts from 2024 with a little summary of each.

Here are the top four blog posts from 2024 with a little summary of each.

It’s not the work, it’s the people. By far the most popular post. Here are some important words from the post: hard work, share, struggle, elbow-to-elbow, fear, crew, extra load, friend, through the wringer, smile, sad, care, easier. And I finished with a challenge.

For the most important people, take a minute and write down your shared experiences and what they mean to you. What would it mean to them if you shared your thoughts and feelings? Why not take a minute and find out? Wouldn’t work be more energizing and fun? If you agree, why not do it? What’s in the way? What’s stopping you?

Why not push through the discomfort and take things to the next level?

Projects, Products, People, and Problems. The post was written within the tight context of product development systems, but I think the tight one-liners have broader applicability. Here are a few of may favorites.

- To get more projects done, do fewer of them.

- Stop starting and start finishing.

- People grow when you create the conditions for their growth.

- When in doubt, help people.

- Trust is all-powerful.

- Whatever business you’re in, you’re in the people business.

Pro Tips for New Product Development Projects. This one was one was narrow and deep. Here are the main themes:

- Effectiveness is more important than efficiency, but we behave otherwise.

- Everyone has too many projects and that’s why they take so long.

- Resources – too highly utilized.

- Novelty – too much of a good thing isn’t wonderful.

I’m thankful! I wrote this for the Thanksgiving holiday. There were four themes: family, health, time, and telling people about your thankfulness. Family – straightforward. Health – appreciating our remaining health because we recognize it flowing away. This one is a little backward, but the Stoics know. And so does Buddha. Time – appreciation of our time, especially when others pull on us. Telling people about our thankfulness – this a great way to multiply the impact of our thankfulness.

Happy New Year and thanks for reading, Mike

Image credit — Anna Sofia Guerreirinho

Resurrecting Manufacturing Through Product Simplification

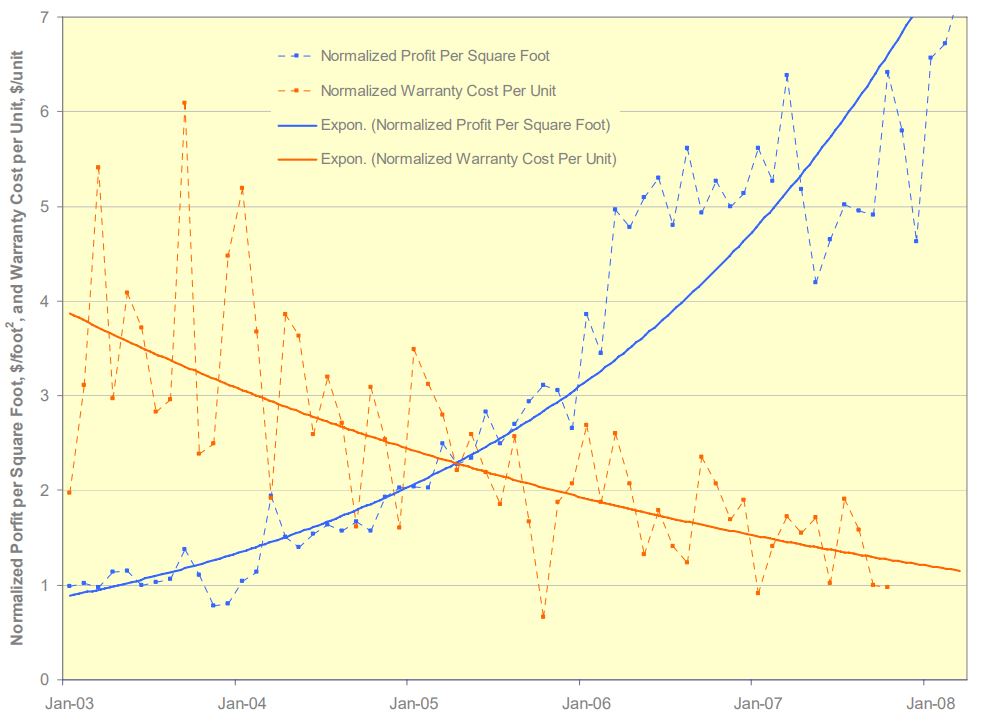

Product simplification can radically improve profits and radically improve product robustness. Here’s a graph of profit per square foot ($/ft^2) which improved by a factor of seven and warranty cost per unit ($/unit), a measure of product robustness), which improved by a factor of four. The improvements are measured against the baseline data of the legacy product which was replaced by the simplified product. Design for Assembly (DFA) was used to simplify the product and Robust Design methods were used to reduce warranty cost per unit.

I will go on record that everyone will notice when profit per square foot increases by a factor of seven.

And I will also go on record that no one will believe you when you predict product simplification will radically improve profit per square foot.

And I will go on record that when warranty cost per unit is radically reduced, customers will notice. Simply put, the product doesn’t break and your customers love it.

But here’s the rub. The graph shows data over five years, which is a long time. And if the product development takes two years, that makes seven long years. And in today’s world, seven years is at least four too many. But take another look at the graph. Profit per square foot doubled in the first two years after launch. Two years isn’t too long to double profit per square foot. I don’t know of a faster way, More strongly, I don’t know of another way to get it done, regardless of the timeline.

I think your company would love to double the profit per square foot of its assembly area. And I’ve shown you the data that proves it’s possible. So, what’s in the way of giving it a try?

For the details about the work, here’s a link – Systematic DFMA Deployment, It Could Resurrect US Manufacturing.

Effectiveness Before Efficiency

Efficient – How do we do more projects with fewer people?

Efficient – How do we do more projects with fewer people?

Effective – Let’s choose the right project.

Would you rather do more projects that miss the mark or fewer that excite the customer?

Efficient – How do we finish the project faster?

Effective – Let’s fully staff the project.

Would you rather burn out the project team or deliver on what the customer wants?

Efficient – How do we reduce product cost by 5%?

Effective – Let’s make customers’ lives easier.

Would you rather reduce the cost or delight the customer?

Efficient – How can we go faster?

Effective – Let’s get it right.

Would you rather go fast and break things or get it right for the customer?

Efficient – How many projects can we run in parallel?

Effective – Let’s fully staff the most important projects.

Would you rather get halfway through four projects or complete two?

Efficient – How do we make progress on as many tasks as possible?

Effective – Let’s work on the critical path.

Would you rather work on things that don’t matter or nail the things that do?

Efficient – How can we complete the most tasks?

Effective – Let’s work on the hardest thing first.

Would you rather learn the whole thing won’t work before or after you waste time on the irrelevant?

If there’s a choice between efficiency and effectiveness, I choose effectiveness.

Image credit — Antarctica Bound

Playing Tetris With Your Project Portfolio

When planning the projects for next year, how do you decide which projects are a go and which are a no? One straightforward way is to say yes to projects when there are resources lined up to get them done and no to all others. Sure, the projects must have a good return on investment but we’re pretty good at that part. But we’re not good at saying no to projects based on real resource constraints – our people and our budgets.

When planning the projects for next year, how do you decide which projects are a go and which are a no? One straightforward way is to say yes to projects when there are resources lined up to get them done and no to all others. Sure, the projects must have a good return on investment but we’re pretty good at that part. But we’re not good at saying no to projects based on real resource constraints – our people and our budgets.

It’s likely your big projects are well-defined and well-staffed. The problem with these projects is usually the project timeline is disrespectful of the work content and the timeline is overly optimistic. If the project timeline is shorter than that of a previously completed project of a similar flavor, with a similar level of novelty and similar resource loading, the timeline is overly optimistic and the project will be late.

Project delays in the big projects block shared resources from moving onto other projects within the appropriate time window which cascades delays into those other projects. And the project resources themselves must stay on the big projects longer than planned (we knew this would happen even before the project started) which blocks the next project from starting on time and generates a second set of delays that rumble through the project portfolio. But the big projects aren’t the worst delay-generating culprits.

The corporate initiatives and infrastructure projects are usually well-staffed with centralized resources but these projects require significant work from the business units and is an incremental demand for them. And the only place the business units can get the resources is to pull them off the (too many) big projects they’ve already committed to. And remember, the timelines for those projects are overly optimistic. The big projects that were already late before the corporate initiatives and infrastructure projects are slathered on top of them are now later.

Then there are small projects that don’t look like they’ll take long to complete, but they do. And though the project plan does not call for support resources (hey, this is a small project you know), support resources are needed. These small projects drain resources from the big projects and the support resources they need. Delay on delay on delay.

Coming out of the planning process, all teams are over-booked with too many projects, too few resources, and timelines that are too short. And then the real fun begins.

Over the course of the year, new projects arise and are started even though there are already too few resources to deliver on the existing projects. Here’s a rule no one follows: If the teams are fully-loaded, new projects cannot start before old ones finish.

It makes less than no sense to start projects when resources are already triple-double booked on existing projects. This behavior has all the downside of starting a project (consumption of resources) with none of the upside (progress). And there’s another significant downside that most don’t see. The inappropriate “starting” of the new project allows the company to tell itself that progress is being made when it isn’t. All that happens is existing projects are further starved for resources and the slow pace of progress is slowed further.

It’s bad form to play Tetris with your project portfolio.

Running too many projects in parallel is not faster. In fact, it’s far slower than matching the projects to the resources on-hand to do them. It’s essential to keep in mind that there is no partial credit for starting a project. There is 100% credit for finishing a project and 0% credit for starting and running a project.

With projects, there are two simple rules. 1) Limit the number of projects by the available resources. 2) Finish a project before starting one.

Image credit – gerlos

The Best Way To Make Projects Go Faster

When there are too many projects, all the projects move too slowly.

When there are too many projects, all the projects move too slowly.

When there are too many projects, adding resources doesn’t help much and may make things worse.

To speed up the important projects, stop the less important projects. There’s no better way.

When there are too many projects, stopping comes before starting.

All projects are important, it’s just that some are more important than others. Stop the lesser ones.

When someone says all projects are equally important, they don’t understand projects.

If all projects are equally important, then they are also equally unimportant and it does not matter which projects are stopped. This twist of thinking can help people choose the right projects to stop.

When there are too many projects, stop two before starting another.

Finishing a project is the best way to stop a project, but that takes too long. Stop projects in their tracks.

There is no partial credit for a project that is 80% complete and blocking other projects. It’s okay to stop the project so others can finish.

Queueing theory says wait times increase dramatically when utilization of shared resources reaches 85%. The math says projects should be stopped well before shared resources are fully booked.

If you want to go faster, stop the lesser projects.

Image credit – Rodrigo Olivera

The Curse of Too Many Active Projects

If you want your new product development projects to go faster, reduce the number of active projects. Full stop.

If you want your new product development projects to go faster, reduce the number of active projects. Full stop.

A rule to live by: If the new product development project is 90% complete, the company gets 0% of the value. When it comes to new product development projects, there’s no partial credit.

Improving the capabilities of your project managers can help you go faster, but not if you have too many active projects.

If you want to improve the speed of decision-making around the projects, reduce the number of required decisions by reducing the number of active projects.

Resource conflicts increase radically as the number of active projects increases. To fix this, you guessed it, reduce the number of active projects.

A project that is run under the radar is the worst type of active project. It sucks resources from the official projects and prevents truth telling because no one can admit the dark project exists.

With fewer active projects, resource intensity increases, the work is done faster, and the projects launch sooner.

Shared resources serve the projects better and faster when there are fewer active projects.

If you want to go faster, there’s no question about what you should do. You should stop the lesser projects to accelerate the most important ones. Full stop.

And if you want to stop some projects, I suggest you try to answer this question: Why does your company think it’s a good idea to have far too many active new product development projects?

Image credit — JOHN K THORNE

The Difficulty of Starting New Projects

Companies that are good at planning their projects create roadmaps spanning about three years, where individual projects are sequenced to create a coordinated set of projects that fit with each other. The roadmap helps everyone know what’s important and helps the resources flow to those most important projects.

Companies that are good at planning their projects create roadmaps spanning about three years, where individual projects are sequenced to create a coordinated set of projects that fit with each other. The roadmap helps everyone know what’s important and helps the resources flow to those most important projects.

Through the planning process, the collection of potential projects is assessed and the best ones are elevated to the product roadmap. And by best, I mean the projects that will generate the most incremental profit. The projects on the roadmap generate the profits that underpin the company’s financial plan and the company is fanatically committed to the financial plan. The importance of these projects cannot be overstated. And what that means is once a project makes it to the roadmap, there’s only one way to get it off the roadmap, and that’s to complete it successfully.

For the next three years, everyone knows what they’ll work on. And they also know what they won’t work on.

The best companies want to be efficient so they staff their projects in a way that results in high utilization. The most common way to do this is to load up the roadmap with too many projects and staff the projects with too few people. The result is a significant fraction of people’s time (sometimes more than 100%) is pre-allocated to the projects on the roadmap. The efficiency metrics look good and it may actually result in many successful launches. But the downside of ultra-high utilization of resources is often forgotten.

When all your people are booked for the next three years on high-value projects, they cannot respond to new opportunities as they arise. When someone comes back from a customer visit and says, “There’s an exciting new opportunity to grow the business significantly!” the best response is “We can’t do that because all our people are committed to the three-year plan.”. The worst response is “Let’s put together a team to create a project plan and do the project.”. With the first response, the project doesn’t get done and zero resources are wasted trying to figure out how to do the project without the needed resources. With the second response, the project doesn’t get done but only after significant resources are wasted trying to figure out how to do the project without the needed resources.

Starting new projects is difficult because everyone is over-booked and over-committed on projects that the company thinks will generate significant (and predictable) profits. What this means is to start a new project in this high-utilization environment, the new project must displace a project on the three-year plan. And remember, the projects that must be displaced are the projects the company has chosen to generate the company’s future profits. So, to become an active project (and make it to the three-year plan) the candidate project must be shown to create more profits, use fewer resources and launch sooner than the projects already on the three-year plan. And this is taller than a tall order.

So, is there a solution? Not really, because the only possible solution is to reduce resource utilization to create unallocated resources that can respond to emergent opportunities when they arise. And that’s not possible because good companies have a deep and unskillful attachment efficiency.

Image credit — Bernard Spragg NZ

Reducing Time To Market vs. Improving Profits

X: We need to decrease the time to market for our new products.

X: We need to decrease the time to market for our new products.

Me: So, you want to decrease the time it takes to go from an idea to a commercialized product?

X: Yes.

Me: Okay. That’s pretty easy. Here’s my idea. Put some new stickers on the old product and relaunch it. If we change the stickers every month, we can relaunch the product every month. That will reduce the time to market to one month. The metrics will go through the roof and you’ll get promoted.

X: That won’t work. The customers will see right through that and we won’t sell more products and we won’t make more money.

Me: You never said anything about making more money. You said you wanted to reduce the time to market.

X: We want to make more money by reducing time to market.

Me: Hmm. So, you think reducing time to market is the best way to make more money?

X: Yes. Everyone knows that.

Me: Everyone? That’s a lot of people.

X: Are you going to help us make more money by reducing time to market?

Me: I won’t help you with both. If you had to choose between making more money and reducing time to market, which would you choose?

X: Making money, of course.

Me: Well, then why did you start this whole thing by asking me for help improving time to market?

X: I thought it was the best way to make more money.

Me: Can we agree that if we focus on making more money, we have a good chance of making more money?

X: Yes.

Me: Okay. Good. Do you agree we make more money when more customers buy more products from us?

X: Everyone knows that.

Me: Maybe not everyone, but let’s not split hairs because we’re on a roll here. Do you agree we make more money when customers pay more for our products?

X: Of course.

Me: There you have it. All we have to do is get more customers to buy more products and pay a higher price.

X: And you think that will work better than reducing time to market?

Me: Yes.

X: And you know how to do it?

Me: Sure do. We create new products that solve our customers’ most important problems.

X: That’s totally different than reducing time to market.

Me: Thankfully, yes. And far more profitable.

X: Will that also reduce the time to market?

Me: I thought you said you’d choose to make more money over reducing time to market. Why do you ask?

X: Well, my bonus is contingent on reducing time to market.

Me: Listen, if the previous new product development projects took two years, and you reduce the time to market to one and half years, there’s no way for you to decrease time to market by the end of the year to meet your year-end metrics and get your bonus.

X: So, the metrics for my bonus are wrong?

Me: Right.

X: What should I do?

Me: Let’s work together to launch products that solve important customer problems.

X: And what about my bonus?

Me: Let’s not worry about the bonus. Let’s worry about solving important customer problems, and the bonuses will take care of themselves.

Image credit — Quinn Dombrowski

X: Me: format stolen from @swardley. Thank you, Simon.

Which new product development project should we do first?

X: Of the pool of candidate new product development projects, which project should we do first?

X: Of the pool of candidate new product development projects, which project should we do first?

Me: Let’s do the one that makes us the most money.

X: Which project will make the most money?

Me: The one where the most customers buy the new product, pay a reasonable price, and feel good doing it.

X: And which one is that?

Me: The one that solves the most significant problem.

X: Oh, I know our company’s most significant problem. Let’s solve that one.

Me: No. Customers don’t care about our problems, they only care about their problems.

X: So, you’re saying we should solve the customers’ problem?

Me: Yes.

X: Are you sure?

Me: Yes.

X: We haven’t done that in the past. Why should we do it now?

Me: Have your previous projects generated revenue that met your expectations?

X: No, they’ve delivered less than we hoped.

Me: Well, that’s because there’s no place for hope in this game.

X: What do you mean?

Me: You can’t hope they’ll buy it. You need to know the customers’ problems and solve them.

X: Are you always like this?

Me: Only when it comes to customers and their problems.

image credit: Kyle Pearce

Three Important Choices for New Product Development Projects

Choose the right project. When you say yes to a new project, all the focus is on the incremental revenue the project will generate and none of the focus is on unrealized incremental revenue from the projects you said no to. Next time there’s a proposal to start a new project, ask the team to describe the two or three most compelling projects that they are asking the company to say no to. Grounding the go/no-go decision within the context of the most compelling projects will help you avoid the real backbreaker where you consume all your product development resources on something that scratches the wrong itch while you prevent those resources from creating something magical.

Choose the right project. When you say yes to a new project, all the focus is on the incremental revenue the project will generate and none of the focus is on unrealized incremental revenue from the projects you said no to. Next time there’s a proposal to start a new project, ask the team to describe the two or three most compelling projects that they are asking the company to say no to. Grounding the go/no-go decision within the context of the most compelling projects will help you avoid the real backbreaker where you consume all your product development resources on something that scratches the wrong itch while you prevent those resources from creating something magical.

Choose what to improve. Give your customers more of what you gave them last time unless what you gave them last time is good enough. Once goodness is good enough, giving customers more is bad business because your costs increase but their willingness to pay does not. Once your offering meets the customers’ needs in one area, lock it down and improve a different area.

Choose how to staff the projects. There is a strong temptation to run many projects in parallel. It’s almost like our objective is to maximize the number of active projects at the expense of completing them. Here’s the thing about projects – there is no partial credit for partially completed projects. Eight active projects that are eight (or eighty) percent complete generate zero revenue and have zero commercial value. For your most important project, staff it fully. Add resources until adding more resources would slow the project. Then, for your next most important project, repeat the process with your remaining resources. And once a project is completed, add those resources to the pool and start another project. This approach is especially powerful because it prioritizes finishing projects over starting them.

“Three Cows” by Sunfox is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski