Archive for the ‘Part Count Reduction’ Category

A Unifying Theory for Manufacturing?

The notion of a unifying theory is tantalizing – one idea that cuts across everything. Though there isn’t one in manufacturing, I think there’s something close: Design simplification through part count reduction. It cuts across everything – across-the-board simplification. It makes everything better. Take a look how even HR is simplified.

The notion of a unifying theory is tantalizing – one idea that cuts across everything. Though there isn’t one in manufacturing, I think there’s something close: Design simplification through part count reduction. It cuts across everything – across-the-board simplification. It makes everything better. Take a look how even HR is simplified.

HR takes care of the people side of the business and fewer parts means fewer people – fewer manufacturing people to make the product, fewer people to maintain smaller factories, fewer people to maintain fewer machine tools, fewer resources to move fewer parts, fewer folks to develop and manage fewer suppliers, fewer quality professionals to check the fewer parts and create fewer quality plans, fewer people to create manufacturing documentation, fewer coordinators to process fewer engineering changes, fewer RMA technicians to handle fewer returned parts, fewer field service technicians to service more reliable products, fewer design engineers to design fewer parts, few reliability engineers to test fewer parts, fewer accountants to account for fewer line items, fewer managers to manage fewer people.

Before I catch hell for the fewer-people-across-the-board language, product simplification is not about reducing people. (Fewer, fewer, fewer was just a good way to make a point.) In fact, design simplification is a growth strategy – more output with the people you have, which creates a lower cost structure, more profits, and new hires.

A unifying theory? Really? Product simplification?

Your products fundamentally shape your organization. Don’t believe me? Take a look at your businesses – you’ll see your product families in your org structure. Take look at your teams – you’ll see your BOM structure in your org structure. Simplify your product to simplify your company across-the-board. Strange, but true. Give it a try. I dare you.

I don’t know the question, but the answer is jobs.

Some sobering facts: (figure and facts from Matt Slaughter)

Some sobering facts: (figure and facts from Matt Slaughter)

- During the Great Recession, US job loss (peak to trough) was 8.4 million payroll jobs were lost (6.1%) and 8.5 million private-sector jobs (7.3%).

- In Sept. 2010 there were 108 million U.S. private-sector payroll jobs, about the same as in March 1999.

- It took 48 months to regain the lost 2.0% of jobs in the 2001 recession. At that rate, the U.S. would again reach 12/07 total payroll jobs around January 2020.

The US has a big problem. And I sure as hell hope we are willing do the hard work and make the hard sacrifices to turn things around.

To me it’s all about jobs. To create jobs, real jobs, the US has got to become a more affordable place to invent, design, and manufacture products. Certainly modified tax policies will help and so will trade agreements to make it easier for smaller companies to export products. But those will take too long. We need something now.

To start, we need affordability through productivity. But not the traditional making stuff productivity, we need inventing and designing productivity.

Here’s the recipe: Invent technology in-country, design and develop desirable products in-country (products that offer real value, products that do something different, products that folks want to buy), make the products in-country, and sell them outside the country. It’s that straightforward.

To me invention/innovation is all about solving technical problems. Solving them more productively creates much needed invention/innovation productivity. The result: more affordable invention/innovation.

To me design productivity is all about reducing product complexity through part count reduction. For the same engineering hours, there are few things to design, fewer things to analyze, fewer to transition to manufacturing. The result: more affordable design.

Though important, we can’t wait for new legislation and trade agreements. To make ourselves more affordable we need to increase productivity of our invention/innovation and design engines while we work on the longer term stuff.

If you’re an engineering leader who wants more about invention/innovation and or design productivity, send me an email at

and use the subject line to let me know which you’re interested in. (Your contact information will remain confidential and won’t be shared with anyone. Ever.)

Together we can turn around the country’s economy.

What if labor was free?

The chase for low cost labor is still alive and well. And it’s still a mistake. Low cost labor is fleeting. Open a plant in a low cost country and capitalism takes immediate hold. Workers see others getting rich off their hard work and demand to be compensated. It’s an inevitable death spiral to a living wage. Time to find the next low cost country.

The chase for low cost labor is still alive and well. And it’s still a mistake. Low cost labor is fleeting. Open a plant in a low cost country and capitalism takes immediate hold. Workers see others getting rich off their hard work and demand to be compensated. It’s an inevitable death spiral to a living wage. Time to find the next low cost country.

The truth is labor costs are an extremely small portion of product cost. (The major cost, by far, is the material and the associated costs of moving it around the planet and managing its movement.) And when design engineers actively design out labor costs (50% reductions are commonplace) it becomes so small it should be ignored altogether. That’s right – ignored. No labor costs. Free labor. What would you do if labor was free?

Eliminate labor costs from the equation and it’s clear what to do. Make it where you can achieve the highest product quality, make it where you can run the smallest batches, and make it where you sell it. Design out labor and you’re on your way.

Design engineers are the key. Only they can design out labor. Management can’t do it without engineers, but engineers can do it without management.

A call to arms for design engineers: organize yourselves, design out labor, and force your company to do the right thing. Your kids and your economy will thank you.

Cure for offshoring: The design side of product development, from Machine Design

A recent article written by Leslie Gordon of Machine Design.

A recent article written by Leslie Gordon of Machine Design.

You have probably seen it yourself: images of Chinese workers toiling in mud-floored factories, each feeding a separate punch press, as if part and parcel of a living, progressive die. The lure of this cheap labor has sent many U.S. manufacturers scrambling overseas to cut production costs.

Although design-for-manufacturing tools that would have made this exodus unnecessary have been around for more than 20 years, companies continue to overlook them, says Mike Shipulski, chief engineer of plasma-cutter manufacturer Hypertherm, hypertherm.com, Hanover, N.H. “Companies are sticking their heads in the sand. Many U.S. firms have become too entrenched in doing things the same way. For example, a typical product-cost breakdown shows material to be the largest cost at about 72%. Overhead is around 24% and labor is only about 4%. The question becomes, why continue to move manufacturing to so-called ‘low-cost countries’ to chase 50% labor reductions for a whopping 2% cost reduction? And it’s sillier than that because companies don’t account for cost increases in shipping and quality control.”

The problem is that companies neglect to efficiently account for cost during the design side of product development….

Back to Basics with DFMA

About eight years ago, Hypertherm embarked on a mission to revamp the way it designed products. Despite the fact its plasma metal-cutting technology was highly regarded and the market leader in the field, the internal consensus was that product complexity could be reduced and thus made more consistently reliable, and there was an across-the-board campaign to reduce product development and manufacturing costs. Instead of entailing novel engineering tactics or state-of-the-art process change, it was a back-to-basics strategy around design for manufacture and assembly (DFMA) that propelled Hypertherm to meet its goals.

About eight years ago, Hypertherm embarked on a mission to revamp the way it designed products. Despite the fact its plasma metal-cutting technology was highly regarded and the market leader in the field, the internal consensus was that product complexity could be reduced and thus made more consistently reliable, and there was an across-the-board campaign to reduce product development and manufacturing costs. Instead of entailing novel engineering tactics or state-of-the-art process change, it was a back-to-basics strategy around design for manufacture and assembly (DFMA) that propelled Hypertherm to meet its goals.

The first step in the redesign program was determining what needed to change. A steering committee with representation from engineering, manufacturing, marketing, and business leadership spent weeks trying to determine what was required from a product standpoint to deliver radical improvements in both product performance and product economics. As a result of that collaboration, the team established aggressive new targets around robustness and reliability in addition to the goal of cutting the parts count and labor costs nearly in half.

Custom Model, exploring customized manufacturing (Mechanical Engineering Magazine)

By reducing parts count and easing assembly, one plasma cutter maker explores customized manufacturing.

By reducing parts count and easing assembly, one plasma cutter maker explores customized manufacturing.

By Jean Thilmany, Associate Editor, Mechanical Engineering Magazine

Ask nearly any engineer or manufacturer about customized manufacturing and—to a person—they’ll all say the same thing: Have you heard the Dell story?

Dell is offered up again and again as the number one example of customized manufacturing done right and done successfully. Shortly after its founding in 1984, Dell began what it calls a configure-to-order approach to manufacturing. The computer company lets customers customize their own computers on the Dell Web site. Buyers select how much memory and disk space they desire and the resulting computer is manufactured and shipped to them.

The approach has helped the computer maker see skyrocket growth. Last year, it held the second-highest spot for desktops and laptops shipped, behind Hewlett Packard, according to market-share numbers from research firm International Data Corp. in Framingham, Mass.

Manufacturers—particularly electronics manufacturers—have long been taking notice. Many of them are investigating how the configure-to-order model could be put to use at their own companies. And some of them have implemented the method—along with the necessary software to get the job done—with great success.

Take Hypertherm Inc. of Hanover, N.H., maker of plasma metal cutting equipment. The company has recently started allowing customers to choose online from ten CNC Edge Pro product configurations, up from three configurations in the former product line, said John Sobr, head designer on the project.

Hypertherm recently redesigned its plasma metal cutting equipment to reduce part count by 27 percent while doubling the number of inputs available. Customers can now choose from ten product configurations.

DFMA Won’t Work

Ask a company or team to do DFMA, and you get a great list of excuses on why DFMA is not applicable and won’t work. Product volumes are too low for DFMA, or too high; product costs are too low, or too high; production processes are too simple, or complex; production mix is too low, or too high. That’s all crap – just excuses to get out of doing the work. DFMA is applicable; it’s just a question of how to prioritize the work.

Ask a company or team to do DFMA, and you get a great list of excuses on why DFMA is not applicable and won’t work. Product volumes are too low for DFMA, or too high; product costs are too low, or too high; production processes are too simple, or complex; production mix is too low, or too high. That’s all crap – just excuses to get out of doing the work. DFMA is applicable; it’s just a question of how to prioritize the work.

To prioritize the work, take a look at product volumes. They’ll put you in the right ballpark. Here are three categories, low, medium, and high volume:

DFMA to Control Controller Design – Design2Part Magazine

Design for Manufacture and Assembly is reported to improve CNC performance, modularity, durability, and serviceability

When Hypertherm (www.hypertherm.com) was getting ready to design its next generation of metal cutting CNCs, the engineering team’s goal was to make improvements. But the controllers, which automate the Hanover, New Hampshire-based company’s advanced cutting tools and systems, were already well-accepted in the marketplace and highly regarded in the industry. So why redesign? And how would they go about it?

See this link for the full article – Using DFMA to Control Controller Design

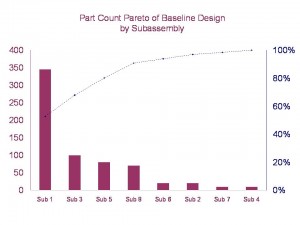

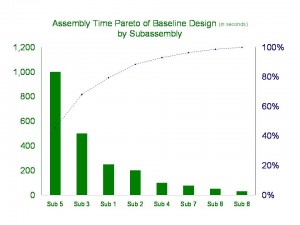

Pareto’s Three Lenses for Product Design

Axiom 1 – Time is short, so make sure you’re working on the most important stuff.

Axiom 1 – Time is short, so make sure you’re working on the most important stuff.

Axiom 2 – You can’t design out what you can’t see.

In product development, these two axioms can keep you out of trouble. They’re two sides of the same coin, but I’ll describe them one at a time and hope it comes together in the end.

With Axiom 1, how do you make sure you’re working on the most important stuff? We all know it’s function first – no learning there. But, sorry design engineers, it doesn’t end with function. You must also design for lean, for cost, and factory floor space. Great. More things to design for. Didn’t you say time was short? How the hell am I going to design for all that?

Now onto the seeing business of Axiom 2. If we agree that lean, cost, and factory floor space are the right stuff, we must “see it” if we are to design it out. See lean? See cost? See factory floor space? You’re nuts. How do you expect us to do that?

Pareto to the rescue – use Pareto charts to identify the most important stuff, to prioritize the work. With Pareto, it’s simple: work on the biggest bars at the expense of the smaller ones. But, Paretos of what?

There is no such thing as a clean sheet design – all new product designs have a lineage. A new design is based on an existing design, a baseline design, with improvements made in several areas to realize more features or better function defined by the product specification. The Pareto charts are created from the baseline design to allow you to see the things to design out (Axiom 2). But what lenses to use to see lean, cost, and factory floor space?

Here are Pareto’s three lenses so see what must be seen:

To lean out lean out your factory, design out the parts. Parts create waste and part count is the surrogate for lean.

To design out cost, measure cost. Cost is the surrogate for cost.

To design out factory floor space, measure assembly time. Since factory floor space scales with assembly time, assembly time is the surrogate for factory floor space.

Now that your design engineers have created the right Pareto charts and can see with the right glasses, they’re ready to focus their efforts on the most important stuff. No boiling the ocean here. For lean, focus on part count of subassembly 1; for cost, focus on the cost of subassemblies 2 and 4; for floor space, focus on assembly time of subassembly 5. Leave the others alone.

Focus is important and difficult, but Pareto can help you see the light.

Fasteners Can Consume 20-50% of Assembly Labor

The data-driven people in our lives tell us that you can’t improve what you can’t measure. I believe that. And it’s no different with product cost. Before improving product cost, before designing it out, you have to know where it is. However, it can be difficult to know what really creates cost. Not all parts and features are created equal; some create more cost than others, and it’s often unclear which are the heavy hitters. Sometimes the heavy hitters don’t look heavy, and often are buried deeply within the hidden factory.

The data-driven people in our lives tell us that you can’t improve what you can’t measure. I believe that. And it’s no different with product cost. Before improving product cost, before designing it out, you have to know where it is. However, it can be difficult to know what really creates cost. Not all parts and features are created equal; some create more cost than others, and it’s often unclear which are the heavy hitters. Sometimes the heavy hitters don’t look heavy, and often are buried deeply within the hidden factory.

Measure, measure, measure. That’s what the black belts say. However, it’s difficult to do well with product cost since our costing methods are hosed up and our measurement systems are limited. What do I mean? Consider fasteners (e.g., nuts, bolts, screws, and washers), the product’s most basic life form. Because fasteners are not on the BOM, they’re not part of product cost. Here’s the party line: it’s overhead to be shared evenly across all the products in a socialist way. That’s not a big deal, right? Wrong. Although fasteners don’t cost much in ones and twos, they do add up. 300-500 pieces per unit times the number of units per year makes for a lot of unallocated and untracked cost. However, a more significant issue with those little buggers is they take a lot of time attach to the product. For example, using standard time data from DFMA software, assembly of a 1/4″ nut with a bolt, locktite, a lockwasher, and cleanup takes 50 seconds. That’s a lot of time. You should be asking yourself what that translates to in your product. To figure it out, multiply the number nut/bolt/washer groupings by 50 seconds and multiply the result by the number of units per year. Actually, never mind. You can’t do the calculation because you don’t know the number of nut/bolt/washer combinations that are in your product. You could try to query your BOMs, but the information is likely not there. Remember, fasteners are overhead and not allocated to product. Have you ever tried to do a cost reduction project on overhead? It’s impossible. Because overhead inflicts pain evenly to all, no one is responsible to reduce it.

With fasteners, it’s like death by a thousand cuts.

The time to attach them can be as much as 20-50% of labor. That’s right, up to 50%. That’s like paying 20-50% of your folks to attach fasteners all day. That should make you sick. But it’s actually worse than that. From Line Design 101, the number of assembly stations is proportional to demand times labor time. Since fasteners inflate labor time, they also inflate the number of assembly stations, which, in turn, inflates the factory floor space needed to meet demand. Would you rather design out fasteners or add 15% to your floor space? I know you can get good deals on factory floor space due to the recession, but I’d still rather design out fasteners.

Even with the amount of assembly labor consumed by fasteners, our thinking and computer systems are blind to them and the associated follow-on costs. And because of our vision problems, the design community cannot be held accountable to design out those costs. We’ve given them the opportunity to play dumb and say things like, “Those fastener things are free. I’m not going to spend time worrying about that. It’s not part of the product cost.” Clearly not an enlightened statement, but it’s difficult to overcome without cost allocation data for the fasteners.

The work-around for our ailing thinking and computer-based cost tracking systems is simple: get the design engineers out to the production floor to build the product. Have them experience first hand how much waste is in the product. They’ll come back with a deep-in-the-gut understanding of how things really are. Then, have them use DFMA software to score the existing design, part-by-part, feature-by-feature. I guarantee everyone will know where the cost is after that. And once they know where the cost is, it will be easy for them to design it out.

I have data to support my assertion that fasteners can make up 20-50% of labor time, but don’t take my word for it. Go out to the factory floor, shut your eyes and listen. You’ll likely hear the never ending song of the nut runners. With each chirp, another nut is fastened to its bolt and washer, and another small bit of labor and factory floor space is consumed by the lowly fastener.

DFA and Lean – A Most Powerful One-Two Punch

Lean is all about parts. Don’t think so? What do your manufacturing processes make? Parts. What do your suppliers ship you? Parts. What do you put into inventory? Parts. What do your shelves hold? Parts. What is your supply chain all about? Parts.

Lean is all about parts. Don’t think so? What do your manufacturing processes make? Parts. What do your suppliers ship you? Parts. What do you put into inventory? Parts. What do your shelves hold? Parts. What is your supply chain all about? Parts.

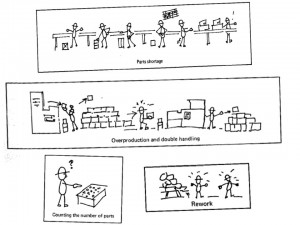

Still not convinced parts are the key? Take a look at the seven wastes and add “of parts” to the end of each one. Here is what it looks like:

- Waste of overproduction (of parts)

- Waste of time on hand – waiting (for parts)

- Waste in transportation (of parts)

- Waste of processing itself (of parts)

- Waste of stock on hand – inventory (of parts)

- Waste of movement (from parts)

- Waste of making defective products (made of parts)

And look at Suzaki’s cartoons. (Click them to enlarge.) What do you see? Parts.

Take out the parts and the waste is not reduced, it’s eliminated. Let’s do a thought experiment, and pretend your product had 50% fewer parts. (I know it’s a stretch.) What would your factory look like? How about your supply chain? There would be: fewer parts to ship, fewer to receive, fewer to move, fewer to store, fewer to handle, fewer opportunities to wait for late parts, and fewer opportunities for incorrect assembly. Loosen your thinking a bit more, and the benefits broaden: fewer suppliers, fewer supplier qualifications, fewer late payments; fewer supplier quality issues, and fewer expensive black belt projects. Most importantly, however, may be the reduction in the transactions, e.g., work in process tracking, labor reporting, material cost tracking, inventory control and valuation, BOMs, routings, backflushing, work orders, and engineering changes.

However, there is a big problem with the thought experiment — there is no one to design out the parts. Since company leadership does not thrust greatness on the design community, design engineers do not have to participate in lean. No one makes them do DFA-driven part count reduction to compliment lean. Don’t think you need the design community? Ask your best manufacturing engineer to write an engineering change to eliminates parts, and see where it goes — nowhere. No design engineer, no design change. No design change, no part elimination.

It’s staggering to think of the savings that would be achieved with the powerful pairing of DFA and lean. It would go like this: The design community would create a low waste design on which the lean community would squeeze out the remaining waste. It’s like the thought experiment; a new product with 50% fewer parts is given to the lean folks, and they lean out the low waste value stream from there. DFA and lean make such a powerful one-two punch because they hit both sides of the waste equation.

DFA eliminates parts, and lean reduces waste from the ones that remain.

There are no technical reasons that prevent DFA and lean from being done together, but there are real failure modes that get in the way. The failure modes are emotional, organizational, and cultural in nature, and are all about people. For example, shared responsibility for design and manufacturing typically resides in the organizational stratosphere – above the VP or Senior VP levels. And because of the failure modes’ nature (organizational, cultural), the countermeasures are largely company-specific.

What’s in the way of your company making the DFA/lean thought experiment a reality?

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski