Archive for the ‘New Normal’ Category

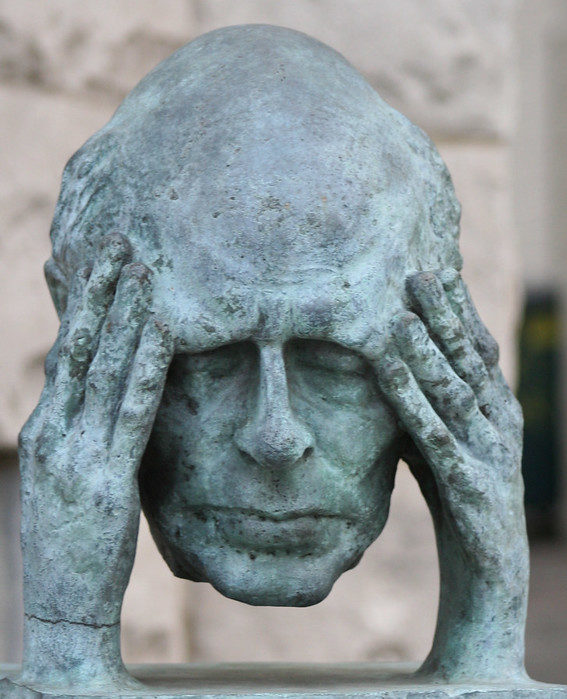

Feel It All

In these trying times, when 30% of Americans cannot pay their rent or mortgage, is it okay to put hard limits on the amount of work we do or to take good care of ourselves or to feel good about taking a vacation?

In these trying times, when 30% of Americans cannot pay their rent or mortgage, is it okay to put hard limits on the amount of work we do or to take good care of ourselves or to feel good about taking a vacation?

With remote work, we commute less, which should give us more time to take care of ourselves. But, do you have more time? If you do, what do you do with your freed-up time? Do you work more? Do you exercise? Do you worry? Do you take the time to feel grateful that you have a job?

When you work from home do you stop and make time to eat lunch? Do you shut off the work and just eat? Or, do you eat while you work? Do you take more time than when you are (or were) in the office or less? If you take more time to eat than when at the office, do you feel good that you’re taking care of yourself? Or, if you take less, do you feel good you’re doing all you can to prevent layoffs? Or, are you simply thankful you still have healthcare benefits?

When you work at home do you attend too many Zoom meetings? If so, what happens to all the work you can’t get done? Do you attend half-heartedly and multitask (work on something else)? Multitasking is disrespectful to the Zoom meeting and the other work, but do you have a choice? To get the work done, do you extend your workday to include your non-commute time? Or, do you decline Zoom meetings because other work is more important? Is it okay to decline a Zoom meeting?

Do you feel good when you set limits to preserve your emotional well-being? Do you preserve your well-being or do you do all you can to keep your job?

And now the tough one. Do you feel good when you go on vacation or do you feel sad because so many citizens have lost their jobs?

Thing is, it’s not or. It’s and.

It’s not that we must feel bad when we work during our non-commute time or feel good when we take care of ourselves or feel thankful for our jobs or feel bad because so many have lost theirs. It’s not or, it’s and. We’ve got to hold all these feelings at once. Tough to do, but we can.

It’s not that we feel bad when we work through lunch or feel good when we go for a walk or feel happy when we do all we can to prevent layoffs or we are thankful we have a job at all. It’s and. We’ve got to handle it all at once. We do what we can to prevent layoffs and take care of ourselves. We feel it all and make the choice.

We attend Zoom meetings and decline them and multitask. We process the three potential realities and choose. The bad ones we decline, the good ones we attend wholeheartedly, and for the others we multitask.

We feel great when we go on vacation and feel sad that others are in a bad way. We feel both at the same time.

Or, as word, is binary, black and white. But today’s realities are not black and white and there is no best way.

If you’re looking for some relief during these trying times, give “and” a try. Feel happy and sad. Feel grateful and scared. Feel it all and see what happens.

I hope it brings you peace.

Image credit — David

The Additive Manufacturing Maturity Model

Additive Manufacturing (AM) is technology/product space with ever-increasing performance and an ever-increasing collection of products. There are many different physical principles used to add material and there are a range of part sizes that can be made ranging from micrometers to tens of meters. And there is an ever-increasing collection of materials that can be deposited from water soluble plastics to exotic metals to specialty ceramics.

Additive Manufacturing (AM) is technology/product space with ever-increasing performance and an ever-increasing collection of products. There are many different physical principles used to add material and there are a range of part sizes that can be made ranging from micrometers to tens of meters. And there is an ever-increasing collection of materials that can be deposited from water soluble plastics to exotic metals to specialty ceramics.

But AM tools and technologies don’t deliver value on their own. In order to deliver value, companies must deploy AM to solve problems and implement solutions. But where to start? What to do next? And how do you know when you’ve arrived?

To help with your AM journey, below a maturity model for AM. There are eight categories, each with descriptions of increasing levels of maturity. To start, baseline your company in the eight categories and then, once positioned, look to the higher levels of maturity for suggestions on how to move forward.

For a more refined calibration, a formal on-site assessment is available as well as a facilitated process to create and deploy an AM build-out plan. For information on on-site assessment and AM deployment, send me a note at mike@shipulski.com.

Execution

- Specify AM machine – There a many types of AM machines. Learn to choose the right machine.

- Justify AM machine – Define the problem to be solved and the benefit of solving it.

- Budget for AM machine – Find a budget and create a line item.

- Pay for machine – Choose the supplier and payment method – buy it, rent to own, credit card.

- Install machine – Choose location, provide necessary inputs and connectivity

- Create shapes/add material – Choose the right CAD system for the job, make the parts.

- Create support/service systems – Administer the job queue, change the consumables, maintenance.

- Security – Create a system for CAD files and part files to move securely throughout the organization.

- Standardize – Once the first machines are installed, converge on a small set of standard machines.

- Teach/Train – Create training material for running AM machine and creating shapes.

Solution

- Copy/Replace – Download a shape from the web and make a copy or replace a broken part.

- Adapt/Improve – Add a new feature or function, change color, improve performance.

- Create/Learn – Create something new, show your team, show your customers.

- Sell Products/Services – Sell high volume AM-produced products for a profit. (Stretch goal.)

Volume

- Make one part – Make one part and be done with it.

- Make five parts – Make a small number of parts and learn support material is a challenge.

- Make fifty parts – Make more than a handful of parts. Filament runs out, machines clog and jam.

- Make parts with a complete manufacturing system – This topic deserves a post all its own.

Complexity

- Make a single piece – Make one part.

- Make a multi-part assembly – Make multiple parts and fasten them together.

- Make a building block assembly – Make blocks that join to form an assembly larger than the build area.

- Consolidate – Redesign an assembly to consolidate multiple parts into fewer.

- Simplify – Redesign the consolidated assembly to eliminate features and simplify it.

Material

- Plastic – Low temperature plastic, multicolor plastics, high performance plastics.

- Metal – Low melting temperature with low conductivity, higher melting temps, higher conductivity

- Ceramics – common materials with standard binders, crazy materials with crazy binders.

- Hybrid – multiple types of plastics in a single part, multiple metals in one part, custom metal alloy.

- Incompatible materials – Think oil and water.

Scale

- 50 mm – Not too large and not too small. Fits the build area of medium-sized machine.

- 500 mm – Larger than the build area of medium-sized machine.

- 5 m – Requires a large machine or joining multiple parts in a building block way.

- 0.5 mm – Tiny parts, tiny machines, superior motion control and material control.

Organizational Breadth

- Individuals – Early adopters operate in isolation.

- Teams – Teams of early adopters gang together and spread the word.

- Functions – Functional groups band together to advance their trade.

- Supply Chain – Suppliers and customers work together to solve joint problems.

- Business Units – Whole business units spread AM throughout the body of their work.

- Company – Whole company adopts AM and deploys it broadly.

Strategic Importance

- Novelty – Early adopters think it’s cool and learn what AM can do.

- Point Solution – AM solves an important problem.

- Speed – AM speeds up the work.

- Profitability – AM improves profitability.

- Initiative – AM becomes an initiative and benefits are broadly multiplied.

- Competitive Advantage – AM generates growth and delivers on Vital Business Objectives (VBOs).

Image credit – Cheryl

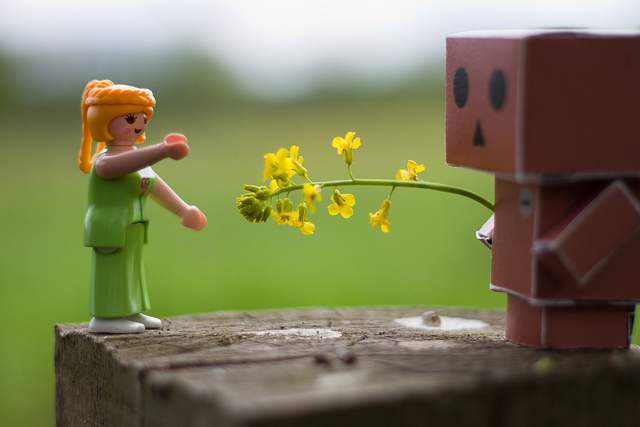

Good teachers don’t always look like teachers.

When you’re laying in your camping tent dead tired and wanting for sleep the last thing you want is a rouge mosquito that dive-bombs you continuously throughout the night. With each sortie, it pushes on your expectations of how things should be. This little creature, so small and so powerless, becomes powerful enough to ruin a good night’s sleep. But, really, the mosquito itself doesn’t become powerful at all. You give the mosquito its power, power generated by a mismatch between what you want (sleep) and what is (a little bug flying around). This mismatch causes you assign intent to the mosquito which leads you to tell yourself a story of an insect on a singular mission to upset you. Truth is, the mosquito is on a mission, a mission to teach you the self destructive power of making little things into big things. The mosquito is your teacher.

When you’re laying in your camping tent dead tired and wanting for sleep the last thing you want is a rouge mosquito that dive-bombs you continuously throughout the night. With each sortie, it pushes on your expectations of how things should be. This little creature, so small and so powerless, becomes powerful enough to ruin a good night’s sleep. But, really, the mosquito itself doesn’t become powerful at all. You give the mosquito its power, power generated by a mismatch between what you want (sleep) and what is (a little bug flying around). This mismatch causes you assign intent to the mosquito which leads you to tell yourself a story of an insect on a singular mission to upset you. Truth is, the mosquito is on a mission, a mission to teach you the self destructive power of making little things into big things. The mosquito is your teacher.

When it’s time to learn, the best teachers show up as if on command. When things have been going well for a while and you’re getting a little stale, your supportive boss contracts yellow fever to make room for your teacher. Your teacher, in the form of your new boss, shows up the first day with all the wrong answers and the strong desire to standardize on them. Your teacher challenges you to look inside for the motivation to elevate your game and demands you bring creativity and clarity of unrivaled proportions. Your terrible boss doesn’t know enough to ask for the right things so you end up solving oblique problems that on the surface seem meaningless. But, because you had to solve a new problem in a new way you come up with a variant that ends up transforming your mainstream business. Your terrible boss is your teacher.

Due to an economic slowdown, the multinational you work for eliminates your division and you lose your job. As you search for a job and collect unemployment you have a little time so you start a crazy side project. It doesn’t matter if it works because it’s just a diversion from your miserable situation, so you try it. And, as it turns out the impossible is actually possible and you start a whole new business on your prototype. Your miserable situation is your teacher.

Instead of getting angry at your new situation and feeling terrible about yourself, embrace the newness and let it be your teacher. Be humble, watch it unfold and see where it takes you. Use it to see yourself differently. Use it to challenge your assumptions.

And, most importantly, as you take the wild ride, hold on to your hearts best intention.

Image credit – Andreas.

Be done with the past.

The past has past, never to come again. But if you tell yourself old stories the past is still with you. If you hold onto your past it colors what you see, shapes what you think and silently governs what you do. Not skillful, not helpful. Old stories are old because things have changed. The old plays won’t work. The rules are different, the players are different, the situation is different. And you are different, unless you hold onto the past.

The past has past, never to come again. But if you tell yourself old stories the past is still with you. If you hold onto your past it colors what you see, shapes what you think and silently governs what you do. Not skillful, not helpful. Old stories are old because things have changed. The old plays won’t work. The rules are different, the players are different, the situation is different. And you are different, unless you hold onto the past.

As a tactic we hold onto the past because of aversion to what’s going on around us. Like an ostrich we bury our head in the sands of the past to protect ourselves from unpleasant weather buffeting us in the now. But there’s no protection. Grasping tightly to the past does nothing more than stop us in our tracks.

If you grasp too tightly to tired technology it’s game over. And it’s the same with your tired business model – grasp too tightly and get run through by an upstart. But for someone who wants to make a meaningful difference, what are the two things that are sacred? The successful technology and successful business model.

It’s difficult for an organization to decide if the successful technology should be reused or replaced. The easy decision is to reuse it. New products come faster, fewer resources are needed because the hard engineering work has been done and the technical and execution risks are lower. The difficult decision is to scrap the old and develop the new. The smart decision is to do both. Launch products with the old technology while working feverishly to obsolete it. These days the half-life of technology is short. It’s always the right time to develop new technology.

The business model is even more difficult to scrap. It cuts across every team and every function. It’s how the company did its work. It’s how the company made its name. It’s how the company made its money. It’s how families paid their mortgages. It’s grasping to the past success of the business model that makes it almost impossible to obsolete.

People grasp onto the past for protection and companies are nothing more than a loosely connected network of people systems. And these people systems have a shared past and a good memory. It’s no wonder why old technologies and business models stick around longer than they should.

To let go of the past people must see things as they are. That’s a slow process that starts with a clear-eyed assessment today’s landscapes. Make maps of the worldwide competitive landscape, intellectual property, worldwide regulatory legislation, emergent technologies (search YouTube) and the sea of crazy business models enabled by the cloud.

The best time to start the landscape analyses was two years ago, but the next best time to start is right now. Don’t wait.

Image credit – John Fife

Established companies must be startups, and vice versa.

For established companies, when times are good, it’s not the right time to try something new – the resources are there but the motivation is not; and when times are tough it’s also the wrong time to try something new – the motivation is there but the breathing room is not. There are an infinite number of scenarios, but for the established company it’s never a good time to try something new.

For established companies, when times are good, it’s not the right time to try something new – the resources are there but the motivation is not; and when times are tough it’s also the wrong time to try something new – the motivation is there but the breathing room is not. There are an infinite number of scenarios, but for the established company it’s never a good time to try something new.

For startup companies, when times are good, it’s the right time to try something new – the resources are there and so is the motivation; and when times are tough it’s also the right time to try something new – the motivation is there and breathing room is a sign of weakness. Again, the scenarios are infinite, but for the startup is always a good time to try something new.

But this is not a binary world. To create new markets and new customers, established companies must be a little bit startup, and to scale, startups must ultimately be a little bit established. This ambidextrous company is good on paper, but in the trenches it gets challenging. (Read Ralph Ohr for an expert treatment.) The establishment regime never wants to do anything new and the startup regime always wants to. There’s no middle ground – both factions judge each other through jaded lenses of ROI and learning rate and mutual misunderstanding carries the day. Trouble is, all companies need both – established companies need new markets and startups need to scale. But it’s more complicated than that.

As a company matures the balance of power should move from startup to established. But this tricky because the one thing power doesn’t like to do is move from one camp to another. This is the reason for the “perpetual startup” and this is why it’s difficult to scale. As the established company gets long in the tooth the balance of power should move from the establishment to the startup. But, again, power doesn’t like to change teams, and established companies squelch their fledgling startup work. But it’s more complicated, still.

The competition is ever-improving, the economy is ever-changing and the planet is ever-warming. New technologies come on-line, and new business models test the waters. Some work, some don’t. Huge companies buy startups just to snuff them out and established companies go away. The environment is ever-changing on all fronts. And the impermanence pushes and pulls on the pendulum of power dynamics.

All companies want predictability, but they’ll never have it. All growth models are built on rearward-looking fundamentals and forward-looking conjecture. Companies will always have the comfort of their invalid models, but will never the predictability they so desperately want. Instead of predictability, companies would be better served by a strong sense of how it wants to go about its business and overpowering genetics of adaptability.

For a strong definition of how to go about business, a simple declaration does nicely. “We want to spend 80% of our resources on established-company work and 20% on startup-company work.” (Or 90-10, or 95-5.) And each quarter, the company measures itself against its charter, and small changes are made to keep things on track. Unless, of course, if the environment changes or the business model runs out of gas. And then the company adapts. It changes its approach and it’s projects to achieve its declared 80-20 charter, or, changes the charter altogether.

A strong charter and adaptability don’t seem like good partners, but they are. The charter brings focus and adaptability brings the change necessary to survive in an every-changing environment. It’s not easy, but it’s effective. As long as you have the right leaders.

Image credit – Rick Abraham1

Dissent Without Reprisal – a key to company longevity

In strategic planning there’s a strong forcing function that causes the organization to converge on a singular, company-wide approach. While this convergence can be helpful, when it’s force is absolute it stifles new ideas. The result is an operating plan that incrementally improves on last year’s work at the expense of work that creates new businesses, sells to new customers and guards against the dark forces of disruptive competition. In times of change convergence must be tempered to yield a bit of diversity in the approach. But for diversity to make it into the strategic plan, dissent must be an integral (and accepted) part of the planning process. And to inject meaningful diversity the dissenting voice must be as load as the voice of convergence.

In strategic planning there’s a strong forcing function that causes the organization to converge on a singular, company-wide approach. While this convergence can be helpful, when it’s force is absolute it stifles new ideas. The result is an operating plan that incrementally improves on last year’s work at the expense of work that creates new businesses, sells to new customers and guards against the dark forces of disruptive competition. In times of change convergence must be tempered to yield a bit of diversity in the approach. But for diversity to make it into the strategic plan, dissent must be an integral (and accepted) part of the planning process. And to inject meaningful diversity the dissenting voice must be as load as the voice of convergence.

It’s relatively easy for an organization to come to consensus on an idea that has little uncertainty and marginal upside. But there can be no consensus, but on an idea with a high degree of uncertainty even if the upside is monumental. If there’s a choice between minimizing uncertainty and creating something altogether new, the strategic process is fundamentally flawed because the planning group will always minimize uncertainty. Organizationally we are set up to deliver certainty, to make our metrics and meet our timelines. We have an organizational aversion to uncertainty, and, therefore, our organizational genetics demand we say no to ideas that create new business models, new markets and new customers. What’s missing is the organizational forcing function to counterbalance our aversion to uncertainty with a healthy grasping of it. If the company is to survive over the next 20 years, uncertainty must be injected into our organizational DNA. Organizationally, companies must be restructured to eliminate the choice between work that improves existing products/services and work that creates altogether new markets, customers, products and services.

When Congress or the President wants to push their agenda in a way that is not in the best long term interest of the country, no one within the party wants to be the dissenting voice. Even if the dissenting voice is right and Congress and the President are wrong, the political (career) implications of dissent within the party are too severe. And, organizationally, that’s why there’s a third branch of government that’s separate from the other two. More specifically, that’s why Justices of the Supreme Court are appointed for life. With lifetime appointments their dissenting voice can stand toe-to-toe with the voice of presidential and congressional convergence. Somehow, for long-term survival, companies must find a way to emulate that separation of power and protect the work with high uncertainty just as the Justices protect the law.

The best way I know to protect work with high uncertainty is to create separate organizations with separate strategic plans, operating plans and budgets. In that way, it’s never a decision between incremental improvement and discontinuous improvement. The decision becomes two separate decisions for two separate teams: Of the candidate projects for incremental improvement, which will be part of team A’s plan? And, of the candidate projects for discontinuous improvement, which will become part of team B’s plan?

But this doesn’t solve the whole challenge because at the highest organizational level, the level that sits above Team A and B, the organizational mechanism for dissent is missing. At this highest level there must be healthy dissent by the board of directors. Meaningful dissent requires deep understanding of the company’s market position, competitive landscape, organizational capability and capacity, the leading technology within the industry (the level, completeness and maturity), the leading technologies in adjacent industries and technologies that transcend industries (i.e., digital). But the trouble is board members cannot spend the time needed to create deep understanding required to formulate meaningful dissent. Yes, organizationally the board of directors can dissent without reprisal, but they don’t know the business well enough to dissent in the most meaningful way.

In medieval times the jester was an important player in the organization. He entertained the court but he also played the role of the dissenter. Organizationally, because the king and queen expected the jester to demonstrate his sharp wit, he could poke fun at them when their ideas didn’t hang together. He could facilitate dissent with a humorous play on a deadly serious topic. It was delicate work, as one step too far and the jester was no more. To strike the right balance the jester developed deep knowledge of the king, queen and major players in the court. And he had to know how to recognize when it was time to dissent and when it was time to keep his mouth shut. The jester had the confidence of the court, knew the history and could see invisible political forces at play. The jester had the organizational responsibility to dissent and the deep knowledge to do it in a meaningful way.

Companies don’t need a jester, but they do need a T-shaped person with broad experience, deep knowledge and the organizational status to dissent without reprisal. Maybe this is a full time board member or a hired gun that works for the board (or CEO?), but either way they are incentivized to dissent in a meaningful way.

I don’t know what to call this new role, but I do know it’s an important one.

Image credit – Will Montague

Scarcity and Abundance

Supply and demand have been joined at the hip since the beginning. When demand is high, the deck is shuffled so supply seems low. The fabricated scarcity drives up prices and shareholders are happy. When demand is low, the competition pushes each other on price. The abundance creates a commodity, and it’s a race to the bottom.

Supply and demand have been joined at the hip since the beginning. When demand is high, the deck is shuffled so supply seems low. The fabricated scarcity drives up prices and shareholders are happy. When demand is low, the competition pushes each other on price. The abundance creates a commodity, and it’s a race to the bottom.

But this is old thinking.

Scarcity isn’t a lever to jack up prices or manipulate relationships, it’s an opportunity to spend your limited resources on the most important work and to build relationships. When you tell a potential partner you want work with them and you are willing to spend your finite resources to make it happen, it’s a huge compliment. Voting with your feet makes a powerful statement that you’re serious about working with them because you think they’re special. You are telling them that you will say no to others so you can say yes to them. Both know they’re part of something important and the free-flowing positivity results in something otherwise impossible.

Scarcity is limiting only if your mental framework thinks it is. If you hoard and hold tightly, scarcity breeds win-lose relationships governed by power dynamics. But if you choose the anti-framework, scarcity creates trust.

Played differently, abundance does not create commodity, it’s opportunity to show others you have enough to spare. In personal relationships, when you share some of your work for free your relationships blossom. When you give it away you are signaling that you have plenty to spare. It’s clear to everyone you are a geyser of new thinking. Here – take this. I’ll make more. These simple words create a foundation of trust which bolsters your personal brand. And because all business relationships are personal relationships, it does the same thing for your company’s brand.

Make it a commodity or give it away – how you see abundance is your choice. The old way breeds bare-knuckled competition. The new way creates a brand steeped in trust.

If you have scarcity, be thankful for it. Allocate your precious resources thoughtfully and with love. Spend your time with the people and causes that matter. It will feel good to everyone, including you. And if you have abundance, be thankful. Choose to develop closer relationships based on trust. Choose to give it away.

Happy Thanksgiving.

image credit — GloriaGarcia

Put your success behind you.

The biggest blocker of company growth is your successful business model. And the more significant it’s historical success, the more it blocks.

Novelty meaningful to the customer is the life force of company growth. The easiest novelty to understand is novelty of product function. In a no-to-yes way, the old product couldn’t do it, but the new one can. And the amount of seconds it takes for the customer to notice (and in the case of meaningful novelty, appreciate) the novelty is in an indication of its significance. If it takes three months of using the product, rigorous data collection and a t-test, that’s not good. If the customer turns on the product and the novelty smashes him in the forehead like a sledgehammer, well, that’s better.

It’s difficult to create a product with meaningful novelty. Engineers know what they know, marketers know what they market, and the salesforce knows how to sell what they sell. And novelty cuts across their comfort. The technology is slightly different, the marketing message diverges a bit, and the sales argument must be modified. The novelty is driven by the product and the people respond accordingly. And, the new product builds on the old one so there’s familiarity.

Where injecting novelty into the product is a challenge, rubbing novelty on the business model provokes a level 5 pucker. Nothing has the stopping power of a proposed change to the business model. Novelty in the product is to novelty in the business model as lightning is to lightning bug – they share a word, but that’s it.

Novelty in the product is novelty of sheet metal, printed circuit boards and software. Novelty in the business model is novelty in how people do their work and novelty in personal relationships. Novelty in the product banal, novelty in the business model is personal.

No tools or best practices can loosen the pucker generated by novelty in the business model. The tired business model has been the backplane of success for longer than anyone can remember. The long-in-the-tooth model has worn deep ruts of success into the organization. Even the all-powerful Lean Startup methodology can’t save you.

The healing must start with an open discussion about the impermanence of all things, including the business model. The most enduring radioactive element has a half-life, and so does the venerable business model, even the most successful.

Where novelty in the product is technical, novelty in the business model is emotional. And that’s what makes it so powerful. Sprinkling the business model with novelty is scary at a deeply personal level – career jeopardy, mortgage insecurity and family volatility are primal drivers. But if you can push through, the rewards are magical.

Your business model has shaped you into an organization that’s optimized to do what it does. You can’t create new markets and sell to new products to new customers without changing your business model. Your business model may have been your secret sauce, but the world’s tastes have changed. It’s time to put your success behind you.

Image credit — MandaRose

The Chief Do-the-Right-Thing Officer – a new role to protect your brand.

Our unhealthy fascination with ever-increasing shareholder value has officially gone too far. In some companies dishonesty is now more culturally acceptable than missing the numbers. (Unless, of course, you get caught. Then, it’s time for apologies.) The sacrosanct mission statement can’t save us. Even the most noble can be stomped dead by the dirty boots of profitability.

Our unhealthy fascination with ever-increasing shareholder value has officially gone too far. In some companies dishonesty is now more culturally acceptable than missing the numbers. (Unless, of course, you get caught. Then, it’s time for apologies.) The sacrosanct mission statement can’t save us. Even the most noble can be stomped dead by the dirty boots of profitability.

Though, legally, companies can self-regulate, practically, they cannot. There’s nothing to balance the one-sided, hedonistic pursuit of profitability. What’s needed is a counterbalancing mechanism of equal and opposite force. What’s needed is a new role that is missing from today’s org chart and does not have a name.

Ombudsman isn’t the right word, but part of it is right – the part that investigates. But the tense is wrong – the ombudsman has after-the-fact responsibility. The ombudsman gets to work after the bad deed is done. And another weakness – ombudsman don’t have equal-and-opposite power of the C-suite profitability monsters. But most important, and what can be built on, is the independent nature of the ombudsman.

Maybe it’s a proactive ombudsman with authority on par with the Board of Directors. And maybe their independence should be similar to a Supreme Court justice. But that’s not enough. This role requires hulk-like strength to smash through the organizational obfuscation fueled by incentive compensation and x-ray vision to see through the magical cloaking power of financial shenanigans. But there’s more. The role requires a deep understanding of complex adaptive systems (people systems), technology, patents and regulatory compliance; the nose of an experienced bloodhound to sniff out the foul; and the jaws of a pit bull that clamp down and don’t let go.

Ombudsman is more wrong than right. I think liability is better. Liability, as a word, has teeth. It sounds like it could jeopardize profitability, which gives it importance. And everyone knows liability is supposed to be avoided, so they’d expect the work to be proactive. And since liability can mean just about anything, it could provide the much needed latitude to follow the scent wherever it takes. Chief Liability Officer (CLO) has a nice ring to it.

[The Chief Do-The-Right-Thing Officer is probably the best name, but its acronym is too long.]

But the Chief Liability Officer (CLO) must be different than the Chief Innovation Officer (CIO), who has all the responsibility to do innovation with none of the authority to get it done. The CLO must have a gavel as loud as the Chief Justice’s, but the CLO does not wear the glasses of a lawyer. The CLO wears the saffron robes of morality and ethics.

Is Chief Liability Officer the right name? I don’t know. Does the CLO report to the CEO or the Board of Directors? Don’t know. How does the CLO become a natural part of how we do business? I don’t know that either.

But what I do know, it’s time to have those discussions.

Image credit – Dietmar Temps

Accountability is not the answer.

People have a natural bias toward doing what was done last time. The behavior is the result of untold generations that evolved to serve a single objective – to survive. Survival is about holding onto what is – protecting the family, providing food and waking up the next morning. In survival mode any energy spent on activities even partially unrelated to food, water and shelter is wasted energy. Any deviation from the worn path creates newness and uncertainty which causes adrenaline to flow and increases caloric burn rate. In survival mode the opportunity cost of those extra calories is larger than the potential benefit of a new experience.

People have a natural bias toward doing what was done last time. The behavior is the result of untold generations that evolved to serve a single objective – to survive. Survival is about holding onto what is – protecting the family, providing food and waking up the next morning. In survival mode any energy spent on activities even partially unrelated to food, water and shelter is wasted energy. Any deviation from the worn path creates newness and uncertainty which causes adrenaline to flow and increases caloric burn rate. In survival mode the opportunity cost of those extra calories is larger than the potential benefit of a new experience.

Today, calories are readily available for most and survival is no longer the objective, yet the bias persists. Today, the bias is not driven by a culture of survivability. It’s driven by a culture of accountability. Accountability forces its own singular focus – make the numbers – and, like survivability, tightly links the consequences of mistakes and shortcomings to the individual. Spend your calories any way you want just don’t miss the numbers.

In a culture of accountability there is no time to rest and recharge. Like the predator that never sleeps, metrics continually keep a hungry eye on the human prey. And like with food and water, any deviation from the worn path of increased throughput and profit is unsafe behavior.

But when the watering hole dries up and the fruit has been picked from the trees, the worn path isn’t the safest path. Frantic foraging is the only real option, but it’s not much safer and certainly no way to go through life. Paradoxically, a culture of accountability, with its intent of reducing the risk of missing the numbers can create far more dangerous failure modes. Where over fishing depletes the fish population and over farming makes for a dust bowl, over reliance on what worked last time can create failure modes that jeopardize survival.

To break the bias and help people do new things, measure new things and talk about new things. Start the next meeting with a review of what’s different. The team will feel energized. And after the discussion, adjourn the meeting because everything else is the same. At the next status meeting, talk only about the surprising insights. With the next email, send praise about the new learning. At team meetings, acknowledge the inherent uncertainty of doing new things and praise it over the potentially catastrophic consequences of over extending the tried-and-true. And for metrics, stop measuring outcomes.

Image credit — Applied Nomadology

Out of Context

“It’s a fact.” is a powerful statement. It’s far stronger than a simple description of what happened. It doesn’t stop at describing a sequence of events that occurred in the past, rather it tacks on an implication of what to think about those events. When “it’s a fact” there’s objective evidence to justify one way of thinking over another. No one can deny what happened, no one can deny there’s only one way to see things and no one can deny there’s only one way to think. When it’s a fact, it’s indisputable.

“It’s a fact.” is a powerful statement. It’s far stronger than a simple description of what happened. It doesn’t stop at describing a sequence of events that occurred in the past, rather it tacks on an implication of what to think about those events. When “it’s a fact” there’s objective evidence to justify one way of thinking over another. No one can deny what happened, no one can deny there’s only one way to see things and no one can deny there’s only one way to think. When it’s a fact, it’s indisputable.

Facts aren’t indisputable, they’re contextual. Even when an event happens right in front of two people, they don’t see it the same way. There are actually two events that occurred – one for each viewer. Two viewers, two viewing angles, two contexts, two facts. Right at the birth of the event there are multiple interpretations of what happened. Everyone has their own indisputable fact, and then, as time passes, the indisputables diverge.

On their own there’s no problem with multiple diverging paths of indisputable facts. The problem arises when we use indisputable facts of the past to predict the future. Cause and effect are not transferrable from one context to another, even if based on indisputable facts. The physics of the past (in the true sense of physics) are the same as the physics of today, but the emotional, political, organizational and cultural physics are different. And these differences make for different contexts. When the governing dynamics of the past are assumed to be applicable today, it’s easy to assume the indisputable facts of today are the same as yesterday. Our static view of the world is the underlying problem, and it’s an invisible problem.

We don’t naturally question if the context is different. Mostly, we assume contexts are the same and mostly we’re blind to those assumptions. What if we went the other way and assumed contexts are always different? What would it feel like to live in a culture that always questions the context around the facts? Maybe it would be healthy to justify why the learning from one situation applies to another.

As the pace of change accelerates, it’s more likely today’s context is different and yesterday’s no longer applies. Whether we want to or not, we’ll have to get better at letting go of indisputable facts. Instead of assuming things are the same, it’s time to look for what’s different.

Image credit — Joris Leermakers

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski