Archive for the ‘Negativity’ Category

Bad Behavior or Unskillful Behavior?

What if you could see everyone as doing their best?

What if you could see everyone as doing their best?

When they are ineffective, what if you think they are using all the skills to the best of their abilities?

What changes when you see people as having a surplus of good intentions and a shortfall of skills?

If someone cannot recognize social cues and behaves accordingly, what does that say about them?

What does it say about you if you judge them as if they recognize those social cues?

Even if their best isn’t all skillful, what if you saw them as doing their best?

When someone treats you unskillfully, maybe they never learned how to behave skillfully.

When someone yells at you, maybe yelling is the only skill they were taught.

When someone treats you unskillfully, maybe that’s the only skill they have at their disposal.

And what if you saw them as doing their best?

Unskillful behavior cannot be stopped with punishment.

Unskillful behavior changes only when new skills are learned.

New skills are learned only when they are taught.

New skills are taught only when a teacher notices a yet-to-be-developed skillset.

And a teacher only notices a yet-to-be-developed skillset when they understand that the unskillful behavior is not about them.

And when a teacher knows the unskillful behavior is not about them, the teacher can teach.

And when teachers teach, new skills develop.

And as new skills develop, behavior becomes skillful.

It’s difficult to acknowledge unskillful behavior when it’s seen as mean, selfish, uncaring, and hurtful.

It’s easier to acknowledge unskillful behavior when it’s seen as a lack of skills set on a foundation of good intentions.

When you see unskillful behavior, what if you see that behavior as someone doing their best?

Unskillful behavior cannot change unless it is called by its name.

And once called by name, skillful behavior must be clearly described within the context that makes it skillful.

If you think someone “should” know their behavior is unskillful, you won’t teach them.

And when you don’t teach them, that’s about you.

If no one teaches you to hit a baseball, you never learn the skill of hitting a baseball.

When their bat always misses the ball, would you think the lesser of them? If you did, what does that say about you?

What if no one taught you how to crochet and you were asked to knit scarf? Even if you tried your best, you couldn’t do it. How could you possibly knit a scarf without developing the skill? How would you want people to see you? Wouldn’t you like to be seen as someone with good intentions that wants to be taught how to crochet?

If you were never taught how to speak French, should I see your inability to speak French as a character defect or as a lack of skill?

We are not born with skills. We learn them.

And we cannot learn skillful behavior unless we’re taught.

When we think they “should” know better, we assume they had good teachers.

When we think their unskillful behavior is about us, that’s about us.

When we punish unskillful behavior, it would be more skillful to teach new skills.

When we use prizes and rewards to change behavior, it would be more skillful to teach new skills.

When in doubt, it’s skillful to think the better of people.

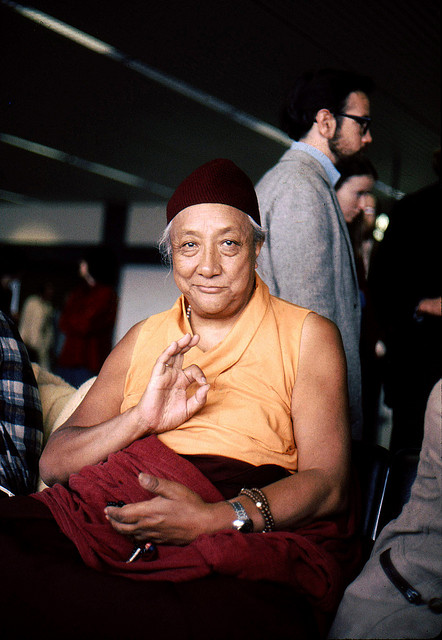

Image credit — Steve Baker

The people part is the hardest part.

The toughest part of all things is the people part.

The toughest part of all things is the people part.

Hold on to being right and all you’ll be is right. Transcend rightness and get ready for greatness.

Embrace hubris and there’s no room for truth. Embrace humbleness and everyone can get real.

Judge yourself and others will pile on. Praise others and they will align with you.

Expect your ideas to carry the day and they won’t. Put your ideas out there lightly and ask for feedback and your ideas will grow legs.

Fight to be right and all you’ll get is a bent nose and bloody knuckles. Empathize and the world is a different place.

Expect your plan to control things and the universe will have its way with you. See your plan as a loosely coupled set of assumptions and the universe will still have its way with you.

Argue and you’ll backslide. Appreciate and you’ll ratchet forward.

See the two bad bricks in the wall and life is hard. See the other nine hundred and ninety-eight and everything gets lighter.

Hold onto success and all you get is rope burns. Let go of what worked and the next big thing will find you.

Strive and get tired. Thrive and energize others.

The people part may be the toughest part, but it’s the part that really matters.

Image credit — Arian Zwegers

A Healthy Dose of Heresy

Anything worth its salt will meet with resistance. More strongly, if you get no resistance, don’t bother.

Anything worth its salt will meet with resistance. More strongly, if you get no resistance, don’t bother.

There’s huge momentum around doing what worked last time. Same as last time but better; build on success; leverage last year’s investment; we know how to do it. Why are these arguments so appealing? Two words: comfort and perceived risk. Why these arguments shouldn’t be so appealing: complacency and opportunity cost.

We think statically and selectively. We look in the rear view mirror, write down what happened and say “let’s do that again.” Hey, why not? We made the initial investment and did the leg work. We created the script. Let’s get some mileage out of it. And we selectively remember the positive elements and actively forget the uncertainty of the moment. We had no idea it was going to work, and we forget that part. It worked better than we imagined and we remember the “working better” part. And we forget we imagined it would go differently. And we forget that was a long time ago and we don’t take the time to realize things are different now. The rules are dynamic, yet our thinking is static.

We compete with the past tense. We did this and they did that, and, therefore, that’s what will happen again. So wrong. We’ve got smarter; they’ve got smarter; battery capacity has tripled; power electronics are twice as efficient; efficiency of solar panels has doubled; CRISPR can edit our genes. The rules are different but the sheet music hasn’t changed. The established players sing the same songs and the upstarts cut them off at the knees.

If you were successful last time and everyone thinks your proposed project is a good idea, ball it up and throw it in the trash. It reeks of stale thinking. If your project plan is dismissed by the experts because it contradicts the tired recipe of success, congratulations! You may be onto something! Stomp on the accelerator and don’t look back.

If your proposal meets with consensus, hang your head and try again. You missed the mark. If they scream “heretic” and want to burn you at the stake, double down. If the CEO isn’t adamantly against it, you’re not trying hard enough. If she throws you out of the room half way through your presentation, you may have a winner!

Yesterday’s recipes for success are today’s worn paths of mediocracy.

If you’re confident it will work, you shouldn’t be. If you’re filled with electric excitement it might actually work and scared to death it might end in a wild fireball of burn metal toxic fumes, what are you waiting for?!

Heretics were burned at the stake because the establishment knew they were right. Goddard was right and the New York Times wasn’t. Decades later they apologized – rockets work is space. And though the Qualifiers and Pope Paul V were unanimous in their dismissal of Galileo and Copernicus, the heretics had it right – the sun is at the center of everything.

Don’t seek out dissent, but if all you get is consensus, be wary. Don’t be adversarial, but if all you get is open arms, question your thesis. Don’t be confrontational, but if all you get is acceptance, something’s wrong.

If there’s no resistance, work on something else.

Image Credit WPI (Robert Goddard’s Lab)

Complaining isn’t a strategy.

It’s easy to complain about how things are going, especially when they’re not going well. But even with the best intentions, complaining doesn’t move the organization in a new direction. Sometimes people complain to attract attention to an important issue. Sometimes it’s out of frustration, sometimes out of sadness and sometimes out of fear, but it’s never the best mechanism.

It’s easy to complain about how things are going, especially when they’re not going well. But even with the best intentions, complaining doesn’t move the organization in a new direction. Sometimes people complain to attract attention to an important issue. Sometimes it’s out of frustration, sometimes out of sadness and sometimes out of fear, but it’s never the best mechanism.

If the intention is to convey importance, why not convey the importance by explaining why it’s important? Why not strip the issue of its charge and use an approach and language that help people understand why it’s important? It’s a simple shift from complaining to explaining, but it can make all the difference. Where complaining distracts, explaining brings people together. And if it’s truly important, why not take the time to have a give-and-take conversation and listen to what others have to say? Instead of listening to respond, why not listen to understand?

If you’re not willing to understand someone else’s position it’s not a conversation.

And if you’re on the receiving end of a complaint, how can you learn to see it as a sign of importance and not as an attack? As the receiver, why not strip it of its charge and ask questions of clarification? Why not deescalate and move things from complaint to conversation? Understanding is not agreeing, but it still a step forward for everyone.

When two sides are divided, complaining doesn’t help, even if it’s well-intentioned. When two sides are divided and there’s strong emotion, the first step is to take responsibility to deescalate. And once emotions are calmed, the next step is to take responsibility to understand the other side. At this stage, there is no requirement to agree, but there can be no hint of disagreement as it will elevate emotions and set progress back to zero. It’s a slow process, but when the issues are highly charged, it’s the fastest way to come together.

If you’re dissatisfied with the negativity, demonstrate positivity. If you want to come together, take the first step toward the middle. If you want to generate the trust needed to move things forward, take action that builds trust.

If you want things to be different, look inside.

Image credit – Ireen2005

The Cycle of Success

There’s a huge amount of energy required to help an organization do new work.

There’s a huge amount of energy required to help an organization do new work.

At every turn the antibodies of the organization reject new ideas. And it’s no surprise. The organization was created to do more of what it did last time. Once there’s success the organization forms structures to make sure it happens again. Resources migrate to the successful work and walls form around them to prevent doing yet-to-be-successful work. This all makes sense while the top line is growing faster than the artificially set growth goal. More resources applied to the successful leads to a steeper growth rate. Plenty of work and plenty of profit. No need for new ideas. Everyone’s happy.

When growth rate of the successful company slows below arbitrary goal, the organization is slow to recognize it and slower to acknowledge it and even slower to assign true root cause. Instead, the organization doubles down on what it knows. More resources are applied, efficiency improvements are put in place, and clearer metrics are put in place to improve accountability. Everyone works harder and works more hours and the growth rate increases a bit. Success. Except the success was too costly. Though total success increased (growth), success per dollar actually decreased. Still no need for new ideas. Everyone’s happy, but more tired.

And then growth turns to contraction. With no more resources move to the successful work, accountability measures increase to unreasonable levels and people work beyond their level of effectiveness. But this time growth doesn’t come. And because people are too focused on doing more of what used to work, new ideas are rejected. When a new idea is proposed, it goes something like this “We don’t need new ideas, we need growth. Now, get out of my way. I’m too busy for your heretical ideas.” There’s no growth and no tolerance for new ideas. No one is happy.

And then a new idea that had been flying under the radar generates a little growth. Not a lot, but enough to get noticed. And when the old antibodies recognize the new ideas and try to reject it, they cannot. It’s too late. The new idea has developed a protective layer of growth and has become a resistant strain. One new idea has been tolerated. Most are unhappy because there’s only one small pocket of growth and a few are happy because there’s one small pocket of growth.

It’s difficult to get the first new idea to become successful, but it’s worth the effort. Successful new ideas help each other and multiply. The first one breaks trail for the second one and the second one bolsters the third. And as these new ideas become more successful something special happens. Where they were resistant to the antibodies they become stronger than the antibodies and eat them.

Growth starts to grow and success builds on success. And the cycle begins again.

Image credit – johnmccombs

Put Yourself Out There

Put yourself out there. Let it hang out. Give it a try. Just do it. The reality is few do it, and fewer do it often. But why?

Put yourself out there. Let it hang out. Give it a try. Just do it. The reality is few do it, and fewer do it often. But why?

In a word, fear. But it cuts much deeper than a word. Here’s a top down progression:

What will they think of your idea? If you summon the courage to say it out loud, your fear is they won’t like it, or they’ll think it’s stupid. But it goes deeper.

What with they think of you? If they think your idea is stupid, your fear is they’ll think you’re stupid. But so what?

How will it conflict with what you think of you? If they think you’re stupid, your fear is it will conflict with what you think of you. Now we’re on to it – full circle.

What do you think of you? It all comes down to your self-image – what you think is it and how you think it will stand up against the outside forces trying to pull it apart. The key is “what you think” and “how you think”. Like all cases, perception is reality; and when it comes to judging ourselves, we judge far too harshly. Our severe self-criticism deflates us far below the waterline of reality, and we see ourselves far shallower than our actions decree.

You’re stronger and more capable than you let yourself think. But no words can help with that; for that, only action will do. Summon the courage to act and take action. Just do it. And to calm yourself before you jump, hold onto this one fact – others’ criticism has never killed anyone. Stung, yes. Killed, no. Plain and simple, you won’t die if you put yourself out there. And even the worst bee stings subside with a little ice.

I’m not sure why we’re so willing to abdicate responsibility for what we think of ourselves, but we do. So where you may have abdicated responsibility in the past, in the now it’s time to take responsibility. It’s time to take responsibility and act on your own behalf.

Fear is real, and you should acknowledge it. But also acknowledge you give fear its power. Feel the fear, be afraid. But don’t succumb to the power you give it.

Put yourself out there. Do it tomorrow. You won’t die. And I bet you’ll surprise others.

But I’m sure you’ll surprise yourself more.

Positivity – The Endangered Species

There’s a lot of negativity around us. But it’s not upfront, unadulterated negativity; it’s behind-the-scenes, hunkering, almost translucent negativity. And it’s divisive.

This type of negativity is so pervasive it’s almost invisible. It’s everywhere; we have processes built around it; have organizations dedicated to it; and we use it daily to drive action.

Take continuous improvement for example. It has been a standard toolset and philosophy for making things better. Yet it’s founded on negativity. It’s not anti-people, anti-culture negativity. (In fact lean and Six Sigma go on their way to emphasize positive culture as a key foundation.) It’s subtle negativity that slowly grinds. Look at the language: reduce defects, eliminate waste, corrective action, tight feedback loops, and eliminate failure modes. There is a negative tint. It’s not in your face, but it’s there.

I’m an advocate of lean and I have advocated for Six Sigma, both of which have moved the needle. But there’s a minimization thread running through them. Both are about eliminating and reducing what is. Sure they have their place, but enough is enough. We need more of creating what isn’t, and bringing to life things that aren’t. We need more maximization.

Negativity has become natural, and positivity has become an endangered species. When there’s a crisis we all come together instinctively to eliminate the bad thing. Yet it’s fourth or fifth nature to come together spontaneously when things go well. Yes, sometimes we celebrate, but it’s the exception. And it’s certainly not our first instinct. (Actually, I don’t think we have a word for spontaneous amplification of positivity. Celebration is the closest word I know, but it’s not the right one.)

Negative feedback is good for processes and positive feedback is good for people. Processes like when their flaws are eliminated, and people like when their strengths are amplified. It’s negativity for processes, and positivity for people.

There should be a rebalancing of negativity and positivity. For every graph of defect reduction over time, there should be a sister plot of the number of good things that happened over time. For every failure mode and effects analysis there should be a fishbone of chart of strengths and the associated actions to amplify them.

It’s natural for us to count bad things and make them go away, and not so natural to count good things and multiply them. Take at the meeting agendas. My bet is there’s far more minimization than maximization.

I usually end my posts with some specific call to action or recommendation. But for this one I don’t have anything all that meaty. But I will tell you how I’m going to move forward. When I see good work, I’m going to publicly acknowledge it and send emails of praise to the manager of the folks who did the good stuff. I’m going to track the number of emails I send and each week increase the number by one. I’m going to schedule regular meetings where I can publicly praise people that display passion. And I’m going to create a control chart of the number of times I amplify positivity.

And most of all I will try to keep in front of me that everything we do is all about people, and with people positivity is powerful.

Own The Behavior

The system is big and complex and its output is outside your control. Trying to control these outputs is a depressing proposition, yet we’re routinely judged (and judge ourselves) on outputs. I think it’s better to focus on system inputs, specifically your inputs to the system.

The system is big and complex and its output is outside your control. Trying to control these outputs is a depressing proposition, yet we’re routinely judged (and judge ourselves) on outputs. I think it’s better to focus on system inputs, specifically your inputs to the system.

When the system responds with outputs different than desired, don’t get upset. It’s nothing personal. The system is just doing its job. It digests a smorgasbord of inputs from many agents just like you and does what it does. Certainly it’s alive, but it doesn’t know you. And certainly it doesn’t respond differently because you’re the one providing input. The system doesn’t take its output personally, and neither should you.

When the system’s output is not helpful, instead of feeling badly about yourself, shift your focus from system output to the input you provide it. (Remember, that’s all you have control over.) Did you do what you said you’d do? Were you generous? We’re you thoughtful? We’re you insightful? Did you give it your all or did you hold back? If you’re happy with the answers you should feel happy with yourself. Your input, your behavior, was just as it was supposed to be. Now is a good time to fall back on the insightful grade school mantra, “You get what you get, and you don’t get upset.”

If your input was not what you wanted, then it’s time to look inside and ask yourself why. At times like these it’s easy to blame others and outside factors for our behavior. But at times like these we must own the input, we must own the behavior. Now, owning the behavior doesn’t mean we’ll behave the same way going forward, it just means we own it. In order to improve our future inputs we’ve got to understand why we behaved as we did, and the first step to better future inputs is owning our past behavior.

Now, replace “system” with “person”, and the argument is the same. You are responsible for your input to the person, and they are responsible for their output (their response). When someone’s output is nonlinear and offensive, you’re not responsible for it, they are. Were you kind? Thoughtful? Insightful? If yes, you get what you get, and you don’t get upset. But what if you weren’t? Shouldn’t you feel responsible for their response? In a word, no. You should feel badly about your input – your behavior – and you should apologize. But their output is about them. They, like the system, responded the way they chose. If you want to be critical, be critical of your behavior. Look deeply at why you behaved as you did, and decide how you want to change it. Taking responsibility for their response gets in the way of taking responsibility for your behavior.

With complex systems, by definition it’s impossible to predict their output. (That’s why they’re called complex.) And the only way to understand them is to perturb them with your input and look for patterns in their responses. What that means is your inputs are well intended and ill informed. This is an especially challenging situation for those of us that have been conditioned (or born with the condition) to mis-take responsibility for system outputs. Taking responsibility for unpredictable system outputs is guaranteed frustration and loss of self-esteem. And it’s guaranteed to reduce the quality of your input over time.

When working with new systems in new ways, it’s especially important to take responsibility for your inputs at the expense of taking responsibility for unknowable system outputs. With innovation, we must spend a little and learn a lot. We must figure out how to perturb the system with our inputs and intelligently sift its outputs for patterns of understanding. The only way to do it is to fearlessly take responsibility for our inputs and fearless let the system take responsibility for its output.

We must courageously engineer and own our behavioral plan of attack, and modify it as we learn. And we must learn to let the system be responsible for its own behavior.

Choose to Choose

There will always be more work than time – no choice there. But, you can choose your mindset. You can choose to be overwhelmed; you can complain; and you can feel bad for yourself. You can also choose to invert it – you only work on vital projects because less important ones aren’t worth your time. Inverted, work is prioritized to make best use of your valuable time. When there’s too much work you can whine and complain, or you can value yourself – your choice

There will always be more work than time – no choice there. But, you can choose your mindset. You can choose to be overwhelmed; you can complain; and you can feel bad for yourself. You can also choose to invert it – you only work on vital projects because less important ones aren’t worth your time. Inverted, work is prioritized to make best use of your valuable time. When there’s too much work you can whine and complain, or you can value yourself – your choice

Most of us don’t choose what we work on, and sometimes it’s work we’ve done before. You can choose to look at as mind numbing tedium, or you can flip it. You can look at it as an opportunity to do your work a better way; to try a more effective approach; to invent something new. With repeat work you can dull it down or try to shine – your choice.

Sometimes we’re asked to do new and challenging work. You can choose to be afraid; you can make excuses; and you can call in sick for the next month. Or you can twist it to your advantage and see it as an opportunity to stretch. With challenging work you can stunt yourself or grow – your choice.

Negativity repels and positivity attracts – it’s time for you to choose.

A Fraternity of Team Players

It’s easy to get caught up in what others think. (I fall into that trap myself.) And it’s often unclear when it happens. But what is clear: it’s not good for anyone.

It’s easy to get caught up in what others think. (I fall into that trap myself.) And it’s often unclear when it happens. But what is clear: it’s not good for anyone.

It’s hard to be authentic, especially with the Fraternity of Team Players running the show, because, as you know, to become a member their bylaws demand you take their secret oath:

I [state your name] do solemnly swear to agree with everyone, even if I think differently. And in the name of groupthink, I will bury my original ideas so we can all get along. And when stupid decisions are made, I will do my best to overlook fundamentals and go along for the ride. And if I cannot hold my tongue, I pledge to l leave the meeting lest I utter something that makes sense. And above all, in order to preserve our founding fathers’ externally-validated sense of self, I will feign ignorance and salute consensus.

It’s not okay that the fraternity requires you check your self at the door. We need to redefine what it means to be a team player. We need to rewrite the bylaws.

I want to propose a new oath:

I [state your name] do solemnly swear to think for myself at all costs. And I swear to respect the thoughts and feelings of others, and learn through disagreement. I pledge to explain myself clearly, and back up my thoughts with data. I pledge to stand up to the loudest voice and quiet it with rational, thoughtful discussion. I vow to bring my whole self to all that I do, and to give my unique perspective so we can better see things as they are. And above all, I vow to be true to myself.

Before you’re true to your company, be true to yourself. It’s best for you, and them.

Separation of church and state, yes; separation of team player and self, no.

The Dark Art of Uncertainty

Engineers hate uncertainty. (More precisely, it scares us to death.) And our role in the company is to snuff it out at every turn, or so we think.

Engineers hate uncertainty. (More precisely, it scares us to death.) And our role in the company is to snuff it out at every turn, or so we think.

To shield ourselves from uncertainty, we take refuge in our analyses. We create intricate computer wizardry to calm our soles. We tell ourselves our analytic powers can stand toe-to-toe with uncertainty. Though too afraid to admit, at the deepest level we know the magic of our analytics can’t dispatch uncertainty. Like He-Who-Should-Not-Should-Be-Named, uncertainty is ever-present and all-powerful. And he last thing we want is to call it by name.

Our best feint is to kill uncertainty before it festers. As soon as uncertainty is birthed, we try slay it with our guttural chant “It won’t work, it won’t work, it won’t work”. Like Dementors, we drain peace, hope, and happiness out of the air around a new idea. We suck out every good feeling and reduce it to something like itself, but soulless. We feed on it until we’re left with nothing but the worst of the idea.1

Insidiously, we conjure premonitions of mythical problems and predict off-axis maladies. And then we cast hexes on innovators when they don’t have answers to our irrelevant quandaries.

But our unnatural bias against uncertainty is misplaced. Without uncertainty there is no learning. Luckily, there are contrivances to battle the dark art of uncertainty.

When the engineering warlocks start their magic, ask them to be specific about their premonitions. Demand they define the problem narrowly – between two elements of the best embodiment; demand they describe the physical mechanisms behind the problem (warlocks are no match for physics); demand they define the problem narrowly in time – when the system spools up, when it slows down, just before it gets hot, right after it cools down. What the warlocks quickly learn is the problem is not the uncertainty around the new idea; the problem is the uncertainty of their knowledge. After several clashes with the talisman of physics, they take off their funny pointy hats, put away their wands, and start contributing in a constructive way. They’re now in the right frame of mind to obsolete their best work

Uncertainty is not bad. Denying it exists is bad, and pretending we can eliminate it is bad. It’s time to demonstrate Potter-like behavior and name what others dare not name.

Uncertainty, Uncertainty, Uncertainty.

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski