Archive for the ‘Level 5 Courage’ Category

Win Hearts and Minds

As an engineering leader you have the biggest profit lever in the company. You lead the engineering teams, and the engineering teams design the products. You can shape their work, you can help them raise their game, and you can help them change their thinking. But if you don’t win their hearts and minds, you have nothing.

As an engineering leader you have the biggest profit lever in the company. You lead the engineering teams, and the engineering teams design the products. You can shape their work, you can help them raise their game, and you can help them change their thinking. But if you don’t win their hearts and minds, you have nothing.

Engineers must see your intentions are good, you must say what you do and do what you say, and you must be in it for the long haul. And over time, as they trust, the profit lever grows into effectiveness. But if you don’t earn their trust, you have nothing.

But even with trust, you must be light on the tiller. Engineers don’t like change (we’re risk reducing beings), but change is a must. But go too quickly, and you’ll go too slowly. You must balance praise of success with praise of new thinking and create a standing-on-the-shoulders-of-giants mindset. But this is a challenge because they are the giants – you’re asking them to stand on their own shoulders.

How do you know they’re ready for new thinking? They’re ready when they’re willing to obsolete their best work and to change their work to make it happen. Strangely, they don’t need to believe it’s possible – they only need to believe in you.

Now the tough part: There’s a lot of new thinking out there. Which to choose?

Whatever the new thinking, it must make sense at a visceral level, and it must be simple. (But not simplistic.) Don’t worry if you don’t yet have your new thinking; it will come. As a seed, here are my top three new thinkings:

Define the problem. This one cuts across everything we do, yet most underwhelm it. To get there, ask your engineers to define their problems on one page. (Not five, one.) Ask them to use sketches, cartoons, block diagram, arrows, and simple nouns and verbs. When they explain the problem on one page, they understand the problem. When they need two, they don’t.

Test to failure. This one’s subtle but powerful. Test to define product limits, and don’t stop until it breaks. No failure, no learning. To get there, resurrect the venerable test-break-fix cycle and do it until you run out of time (product launch.) Break the old product, test-break-fix the new product until it’s better.

Simplify the product. This is where the money is. Product complexity drives organizational complexity – simplify the product and simply everything. To get there, set a goal for 50% part count reduction, train on Design for Assembly (DFA), and ask engineering for part count data at every design review.

I challenge you to challenge yourself: I challenge you to define new thinking; I challenge you to help them with it; I challenge you to win their hearts and minds.

Stop Doing – it will double your productivity

For the foreseeable future, there will be more work than time. Yet year-on-year we’re asked to get more done and year-on-year we pull it off. Most are already at our maximum hour threshold, so more hours is not the answer. The answer is productivity.

For the foreseeable future, there will be more work than time. Yet year-on-year we’re asked to get more done and year-on-year we pull it off. Most are already at our maximum hour threshold, so more hours is not the answer. The answer is productivity.

Like it or not, there are physical limits to the number of hours worked. At a reasonable upper our bodies need sleep and our families deserve our time. And at the upper upper end, a 25 hour day is not possible. Point is, at some point we draw a line in the sand and head home for the day. Point is, we have finite capacity.

As a thought experiment, pretend you’re at (or slightly beyond) your reasonable upper limit and not going to work more hours. If your work stays the same, your output will be constant and productivity will be zero. But since productivity will increase, your work must change. No magic here, but how to change your work?

Changing your work is about choice – the choice to change your work. You know your work best and you’re the best one to choose. And your choice comes down to what you’ll stop doing.

The easiest thing to stop doing is work you’ve just completed. It’s done, so stop. Finish one, start one is the simplest way to go through life, but it’s not realistic (and productivity does not increase.) Still, it makes for a good mantra: Stop starting and start finishing.

The next things to stop are activities that have no value. Stop surfing and stop playing Angry Birds. Enough said. (If you need professional help to curb your surfing habit, take a look at Leechblock. It helped me.)

The next things to stop are meetings. Here are some guidelines:

- If the meeting is not worth a meeting agenda, don’t go.

- If it’s a status meeting, don’t go – read the minutes.

- If you’re giving status at a status meeting, don’t go – write a short report.

- If there’s a decision to be made, and it affects you, go.

The next thing to stop is email. The best way I know to kick the habit is a self-mandated time limit. Here are some specific suggestions:

- Don’t automatically connect your email to the server – make yourself connect to it.

- Create an email filter for the top ten most important people (You know who they are.) to route them to your Main inbox. Everyone else is routed to a Read Later inbox.

- Check email for fifteen minutes in the morning and fifteen minutes in the afternoon. Start with the Main inbox (important people) and move to the Read Later inbox if you have time. If you don’t have time for the Read Laters, that’s okay – read them later.

- Create an email rule that automatically deletes unread emails in two days and read ones in one.

- Let bad things happen and adjust your email filters and rules accordingly.

Once you’ve chosen to stop the non-productive work, you’ll have more than doubled your productive hours which will double your productivity. That’s huge.

The tough choices come when you must choose between two (or more) sanctioned projects. There are also tricks for that, but that’s different post.

Run From Your Success

Don’t worry about your biggest competitor – they’re not your biggest competitor. You’ve not met your biggest competitor. Your biggest competitor is either from another industry or it’s three guys and a dog toiling away in their basement.

Don’t worry about your biggest competitor – they’re not your biggest competitor. You’ve not met your biggest competitor. Your biggest competitor is either from another industry or it’s three guys and a dog toiling away in their basement.

Certainly it’s impossible to worry about a competitor we’ve not met, but that’s just what we’ve got to do. We’ve got to use thought-shifting mechanisms to help us see ourselves from the framework of our unknown competitor.

Our unknown competitor doesn’t have much – no fully functional products, no fully built-out product lines, and no market share. And that’s where we must shift our thinking – to a place of scarcity – so we can see ourselves from their framework. We’ve got to look down (in the S-curve sense), sit ourselves at the bottom, and look up at our successful selves. It’s the best way to move from self-cherishing to self-dismantling.

To start, we must create our logical trajectory. First, define where we are and where we came from. Then, with a ruler aligned to the points, extend a line into the future. That’s our logical trajectory – an extrapolation in the direction of our success. Along this line we will do more of what got us here, more of what we’ve done. Without giving ground on any front, we will protect market share and build more. We’ve now defined how we see ourselves. We’ve now defined the thinking that could be our undoing.

Now we must force enlightenment on ourselves. We create an illogical trajectory where we see ourselves from a success-less framework. In this framework less is more; more-of-the-same is displaced with more-of-something-else; and success is a weakness. We know we’re sitting in the rights space when the smallest slice of incremental market share looks like a big, juicy bite – like it looks to our unknown competitor.

The disruptive technology created by our unknown competitor will start innocently. Immature at first, the disruptive technology will do most things poorly but do one thing better. Viewed from our success framework we will see only limitations and dismiss it, while our unknown competitors will see opportunity. We will see the does-most-things-poorly part and they’ll see the one-thing-better part. They will sell to a small segment that values the one-thing-better part.

In another variant, an immature disruptive technology will do less with far less. From our success framework we will see “less” while from their scarcity framework they will see “more”. They will sell a simpler product that does less for a price that’s far less. (And make money.)

Here’s the one that’s most frightening: an immature technology that does all things poorly but does them without a fundamental limitation of our technology. From our framework the limitation is so fundamental we won’t let ourselves see it. This limitation is un-seeable because we’ve built our business around it. (Think Kodak film.) This flavor of disruptive technology can put our business model out of business, yet we’ll dismiss it.

We’ll know we’ve shifted our thinking to the right place when we see our unknown competitors not as bottom-feeders but as hungry competitors who see our scraps as a smorgasbord.

We’ll know our thinking’s right when see not self-destruction, but self-disruption.

We’ll know all is right with the world we’re working on disruptive technologies to disrupt ourselves, disruptive technologies with the potential to create business models so compelling that we’ll gladly run from our success.

Can’t Say NO

- Yes is easy, no is hard.

- Sometimes slower is faster.

- Yes, and here’s what it will take:

- The best choose what they’ll not do.

- Judge people on what they say no to.

- Work and resources are a matched pair.

- Define the work you’ll do and do just that.

- Adding scope is easy, but taking it out is hard.

- Map yes to a project plan based on work content.

- Challenge yourself to challenge your thinking on no.

- Saying yes to something means saying no to something else.

- The best have chosen wrong before, that’s why they’re the best.

- It’s better to take one bite and swallow than take three and choke.

Be Your Stiffest Competitor

Your business is going away. Not if, when. Someone’s going to make it go away and it might as well be you. Why not take control and make it go away on your own terms? Why not make it go away and replace it with something bigger and better?

Your business is going away. Not if, when. Someone’s going to make it go away and it might as well be you. Why not take control and make it go away on your own terms? Why not make it go away and replace it with something bigger and better?

Success is good, but fleeting. Like a roller coaster with up-and-up clicking and clacking, there’s a drop coming. But with a roller coaster we expect it – there’s always a drop. (That’s what makes it a roller coaster.) We get ready for it, we brace ourselves. Half-scared and half-excited, electricity fills us, self-made fight-or-flight energy that keeps us safe. I think success should be the same – we should expect the drop.

More strongly we should manage the drop, make it happen on our terms. But that’s going to be difficult. Success makes it easy to unknowingly slip into protecting-what-we-have mode. If we’re to manage the drop, we must learn to relish it like the roller coaster. As we’re ascending – on the way up – we must learn to create a healthy discomfort around success, like the sweaty-palm feeling of the roller coaster’s impending wild ride.

A sky-is-falling approach won’t help us embrace the drop. With success all around, even the best roller coaster argument will be overpowered. The argument must be based on positivity. Acknowledge success, celebrate it, and then challenge your organization to improve on it. Help your organization see today’s success as the foundation for the future’s success – like standing on the shoulders of giants. But in this case, the next level of success will be achieved by dismantling what you’ve built.

No one knows what the future will be, other than there will be increased competition. Hopefully, in the future, your stiffest competitor will be you.

Manage For The Middle

Year-end numbers, quarter-to-quarter earnings, monthly production, week-to-week payroll. With today’s hyper-competition, today’s focus is today. Close-in focus is needed, it drives good stuff – vital few, productivity, quality, speed, and stock price. Without question, the close-in lens has value.

Year-end numbers, quarter-to-quarter earnings, monthly production, week-to-week payroll. With today’s hyper-competition, today’s focus is today. Close-in focus is needed, it drives good stuff – vital few, productivity, quality, speed, and stock price. Without question, the close-in lens has value.

But there’s a downside to this lens. Like a microscope, with one eye closed and the other looking through the optics, the fine detail is clear, but the field of view is small. Sure the object can be seen, but that’s all that can be seen – a small circle of light with darkness all around. It’s great if you want to see the wings of a fly, but not so good if you want to see how the fly got there.

Millennia, centuries, grand children, children. With today’s hyper-competition, today’s focus is today. Long-range focus is needed, it drives good stuff – infrastructure, building blocks, strategic advantage. Though it’s an underused lens, without question, the far-out lens has value.

But there’s a downside to this lens. Like a telescope, with one eye closed and the other looking through the optics, the field of view is enormous, but the detail is not there. Sure the far off target can be seen, but no details – a small circle of light without resolution. It’s great if you want to see a distant landscape, but not so good if you want to know what the trees look like.

What we need is a special set of binoculars. In the left is a microscope to see close-in – the details – and zoom out for a wider view – the landscape. In the right is a telescope to see far-out – the landscape – and zoom in for a tighter view – the details.

Unfortunately the physics of business don’t allow overlap between the lenses. The microscope cannot zoom out enough and the telescope cannot zoom in enough. There’s always a gap, the middle is always out of focus, unclear. Sure, we estimate, triangulate, and speculate (some even fabricate), but the middle is fuzzy at best.

It’s easy to manage for the short-term or long-term. But the real challenge is to manage for the middle. Fuzzy, uncertain, scary – it takes judgment and guts to manage for the middle. And that’s just where the best like to earn their keep.

Trust is better than control.

Although it’s more important than ever, trust is in short supply. With everyone doing three jobs, there’s really no time for anything but a trust-based approach. Yet we’re blocked by the fear that trust means loss of control. But that’s backward.

Although it’s more important than ever, trust is in short supply. With everyone doing three jobs, there’s really no time for anything but a trust-based approach. Yet we’re blocked by the fear that trust means loss of control. But that’s backward.

Trust is a funny thing. If you have it, you don’t need it. If you don’t have it, you need it. If you have it, it’s clear what to do – just behave like you should be trusted. If you don’t have it, it’s less clear what to do. But you should do the same thing – behave like you should be trusted. Either way, whether you have it or not, behave like you should be trusted.

Trust is only given after you’ve behaved like you should be trusted. It’s paid in arrears. And people that should be trusted make choices. Whether it’s an approach, a methodology, a technology, or a design, they choose. People that should be trusted make decisions with incomplete data and have a bias for action. They figure out the right thing to do, then do it. Then they present results – in arrears.

I can’t choose – I don’t have permission. To that I say you’ve chosen not to choose. Of course you don’t have permission. Like trust, it’s paid in arrears. You don’t get permission until you demonstrate you don’t need it. If you had permission, the work would not be worth your time. You should do the work you should have permission to do. No permission is the same as no trust. Restating, I can’t choose – I don’t have trust. To that I say you’ve chosen not to choose.

There’s a misperception that minimizing trust minimizes risk. With our control mechanisms we try to design out reliance on trust – standardized templates, standardized process, consensus-based decision making. But it always comes down to trust. In the end, the subject matter experts decide. They decide how to fill out the templates, decided how to follow the process, and decide how consensus decisions are made. The subject matter experts choose the technical approach, the topology, the materials and geometries, and the design details. Maybe not the what, but they certainly choose the how.

Instead of trying to control, it’s more effective to trust up front – to acknowledge and behave like trust is always part of the equation. With trust there is less bureaucracy, less overhead, more productivity, better work, and even magic. With trust there is a personal connection to the work. With trust there is engagement. And with trust there is more control.

But it’s not really control. When subject matter experts are trusted, they seek input from project leaders. They know their input has value so they ask for context and make decisions that fit. Instead of a herd of cats, they’re a swarm of bees. Paradoxically, with a trust-based approach you amplify the good parts of control without the control parts. It’s better than control. It’s where ideas, thoughts and feelings are shared openly and respectfully; it’s where there’s learning through disagreement; it’s where the best business decisions are made; it’s where trust is the foundation. It’s a trust-based approach.

The Bottom-Up Revolution

The No. 1 reason initiatives are successful is support from top management. Whether it’s lean, Six Sigma, Design for Six Sigma or any program, top management support is vital. No argument. It’s easy with full support, but there’s never enough to go around.

The No. 1 reason initiatives are successful is support from top management. Whether it’s lean, Six Sigma, Design for Six Sigma or any program, top management support is vital. No argument. It’s easy with full support, but there’s never enough to go around.

But that’s the way it should be. Top management has a lot going on, much of it we don’t see: legal matters, business relationships, press conferences, the company’s future. If all programs had top management support, they would fail due to resource cannibalization. And we’d have real fodder for our favorite complaint—too many managers.

When there’s insufficient top management support, we have a choice. We can look outside and play the blame game. “This company doesn’t do anything right.” Or we can look inside and choose how we’ll do our work. It’s easy to look outside, then fabricate excuses to do nothing. It’s difficult to look inside, then create the future, especially when we’re drowning in the now. Layer on a new initiative, and frustration is natural. But it’s a choice.

We will always have more work than time….

Time To Think

We live in a strange time where activity equals progress and thinking does not. Thinking is considered inactivity – wasteful, non-productive, worse than sleeping. (At least napping at your desk recharges the battery.) In today’s world there is little tolerance for thinking.

We live in a strange time where activity equals progress and thinking does not. Thinking is considered inactivity – wasteful, non-productive, worse than sleeping. (At least napping at your desk recharges the battery.) In today’s world there is little tolerance for thinking.

For those that think regularly – or have thought once or twice over the last year – we know thinking is important. If we stop and think, everyone thinks thinking is important. It’s just that we’re too busy to stop and think.

It’s difficult to quantify how bad things are – especially if we’re to compare across industries and continents. Sure it’s easy (and demoralizing) to count the hours spent in meetings or the time spent wasting time with email. But they don’t fully capture a company’s intolerance to thinking. We need a tolerance metric and standardized protocol to measure it.

I’ve invented the Thinking Tolerance Metric, TTM, and a way to measure it. Here’s the protocol: On Monday morning – at your regular start time – find a quiet spot and think. (Your quiet spot can be home, work, a coffee shop, or outside.) No smart phone, no wireless, no meetings. Don’t talk to anyone. Start the clock and start thinking. Think all day.

The clock stops when you receive an email from your boss stating that someone complained about your lack of activity. At the end of the first day, turn on your email and look for the complaint. If it’s there, use the time stamp to calculate TTM using Formula 1:

a

TTM = Time stamp of first complaint – regular start time. [1]

a

If TTM is measured in seconds or minutes, that’s bad. If it’s an hour or two, that’s normal.

If there is no complaint for the entire day, repeat the protocol on day two. Go back to your quiet spot and think. At the end of day two, check for the complaint. Repeat until you get one. Calculate TTM using Formula 1.

Once calculated, send me your data by including it in a comment to this post. I will compile the data and publish it in a follow-on post. (Please remember to include your industry and continent.)

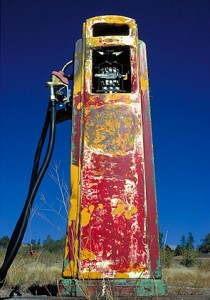

Out Of Gas

You know you’re out of gas when:

You know you’re out of gas when:

- You answer email punctually instead of doing work.

- You trade short term bliss for long term misery.

- You accept an impossible deadline.

- You sit through witless meetings.

- You comply with groupthink.

- You condone bad behavior.

- You placate your boss.

- You write a short post with a bulletized list — because it’s easier.

Amplify The Social Benefits of Your Products

To do g ood for the planet and make lots of money (or the other way around), I think companies should shift from an economic framework to a social one. Green products are a good example. Facts are facts: today, as we define cost, green products cost more; burning fossil fuel is the lowest cost way to produce electricity and move stuff around (people, products, raw material). Green products are more expensive and do less, yet they sell. But the economic benefits don’t sell, the social ones do. Lower performance and higher costs of green products should be viewed not as weaknesses, but as strengths.

ood for the planet and make lots of money (or the other way around), I think companies should shift from an economic framework to a social one. Green products are a good example. Facts are facts: today, as we define cost, green products cost more; burning fossil fuel is the lowest cost way to produce electricity and move stuff around (people, products, raw material). Green products are more expensive and do less, yet they sell. But the economic benefits don’t sell, the social ones do. Lower performance and higher costs of green products should be viewed not as weaknesses, but as strengths.

Green technologies are immature and expensive, but there’s no questions they’re the future. Green products will create new markets, and companies that create new markets will dominate them. The first sales of expensive green products are made by those who can afford them; they put their money where their mouths are and pay more for less to make a social statement. In that way, the shortcoming of the product amplifies the social statement. It’s clear the product was purchased for the good of others, not solely for the goodness of the product itself. The sentiment goes like this: This product is more expensive, but I think the planet is worth my investment. I’m going to buy, and feel good doing it.

The Prius is a good example. While its environmental benefits can be debated, it clearly does not drive as well as other cars (handling, acceleration, breaking). Yet people buy them. People buy them because that funny shape is mapped to a social statement: I care about the environment. Prius generates a signal: I care enough about the planet to put my money where my mouth is. It’s a social statement. I propose companies use a similar social framework to create new markets with green products that do less, cost more, and overtly signal their undeniable social benefit. (To be clear, the product should undeniably make the planet happy.)

The company that creates a new market owns it. (At least it’s theirs to lose). Early sales impregnate the brand with the green product’s important social statement, and the new market becomes the brand and its social statement. And more than that, early sales enable the company to work out the bugs, allow the technology to mature, and yield lower costs. Lower costs enable a cost effective market build-out.

Don’t shy away from performance gaps of green technologies, embrace them; acknowledge them to amplify the social benefit. Don’t shy away from a high price, embrace it; acknowledge the investment to amplify the social benefit. Be truthful about performance gaps, price it high, and proudly do good for the planet.

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski