Archive for the ‘How To’ Category

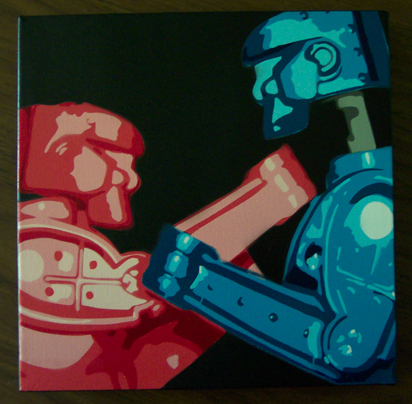

Diabolically Simple Prototypes

Ideas are all talk and no action. Ideas are untested concepts that have yet to rise to the level of practicality. You can’t sell an idea and you can’t barter with them. Ideas aren’t worth much.

Ideas are all talk and no action. Ideas are untested concepts that have yet to rise to the level of practicality. You can’t sell an idea and you can’t barter with them. Ideas aren’t worth much.

A prototype is a physical manifestation of an idea. Where ideas are ethereal, prototypes are practical. Where ideas are fuzzy and subject to interpretation, prototypes are a sledge hammer right between the eyes. There is no arguing with a prototype. It does what it does and that’s the end of that. You don’t have to like what a prototype stands for, but you can’t dismiss it. Where ideas aren’t worth a damn, prototypes are wholly worth every ounce of effort to create them.

If Camp A says it will work and Camp B says it won’t, a prototype will settle the disagreement pretty quickly. It will work or it won’t. And if it works, the idea behind it is valid. And if it doesn’t, the idea may be valid, but a workable solution is yet-to-be discovered. Either way, a prototype brings clarity.

Prototypes are not elegant. Prototypes are ugly. The best ones do one thing – demonstrate the novel idea that underpins them. The good ones are simple, and the best ones are diabolically simple. It is difficult to make diabolically simple prototypes (DSPs), but it’s a skill that can be learned. And it’s worth learning because DSPs come to life in record time. The approach with DSPs is to take the time up front to distill the concept down to its essence and then its all-hands-on-deck until it’s up and running in the lab.

But the real power of the DSP is that it drives rapid learning. When a new idea comes, it’s only a partially formed. The process of trying to make a DSP demands the holes are filled and blurry parts are brought into focus. The DSP process demands a half-baked idea matures into fully-baked physical embodiment. And it’s full-body learning. Your hands learn, your eyes learn and your torso learns.

If you find yourself in a disagreement of ideas, stop talking and start making a prototype. If the DSP works, the disagreement is over.

Diabolically simple prototypes end arguments. But, more importantly, they radically increase the pace of learning.

Image credit – snippets101

The Causes and Conditions for Innovation

Everyone wants to do more innovation. But how? To figure out what’s going on with their innovation programs, companies spend a lot of time to put projects into buckets but this generates nothing but arguments about whether projects are disruptive, radical innovation, discontinuous, or not. Such a waste of energy and such a source of conflict. Truth is, labels don’t matter. The only thing that matters is if the projects, as a collection, meet corporate growth objectives. Sure, there should be a short-medium-long look at the projects, but, for the three time horizons the question is the same – Do the projects meet the company’s growth objectives?

Everyone wants to do more innovation. But how? To figure out what’s going on with their innovation programs, companies spend a lot of time to put projects into buckets but this generates nothing but arguments about whether projects are disruptive, radical innovation, discontinuous, or not. Such a waste of energy and such a source of conflict. Truth is, labels don’t matter. The only thing that matters is if the projects, as a collection, meet corporate growth objectives. Sure, there should be a short-medium-long look at the projects, but, for the three time horizons the question is the same – Do the projects meet the company’s growth objectives?

To create the causes and conditions for innovation, start with a clear growth objective by geography. Innovation must be measured in dollars.

Good judgement is required to decide if a project is worthy of resources. The incremental sales estimates are easy to put together. The difficult parts are deciding if there’s enough sizzle to cause customers to buy and deciding if the company has the chops to do the work. The difficulty isn’t with the caliber of judgement, rather it’s insufficient information provided to the people that must use their good judgement. In shorth, there is poor clarity on what the projects are about. Any description of the projects blurry and done at a level of abstraction that’s too high. Good judgement can’t be used when the picture is snowy, nor can it be effective with a flyby made in the stratosphere.

To create the causes and conditions for innovation, demand clarity and bedrock-level understanding.

To guarantee clarity and depth, use the framework of novel, useful, successful. Give the teams a tight requirement for clarity and depth and demand they meet it. For each project, ask – What is the novelty? How is it useful? When the project is completed, how will everyone be successful?

A project must deliver novelty and the project leader must be able to define it on one page. The best way to do this is to create physical (functional) model of the state-of-the-art system and modify it with the newness created by the project (novelty called out in red). This model comes in the form of boxes that describe the system elements (simple nouns) and arrows that define the actions (simple verbs). Think hammer (box – simple noun) hits (arrow -simple verb) nail (box – simple noun) as the state-of-the-art system and the novelty in red – a thumb protector (box) that blocks (arrow) hammer (box). The project delivers a novel thumb protector that prevents a smashed thumb. The novelty delivered by the project is clear, but does it pass the usefulness test?

To create the causes and conditions for innovation, demand a one-page functional model that defines and distills down to bedrock level the novelty created by the project. And to help the project teams do it, hire a good teach teacher and give them the tools, time and training.

The novelty delivered by a project must be useful and the project leader must clearly define the usefulness on one page. The best way to do this is with a one page hand sketch showing the customer actively using the novelty. In a jobs-to-be-done way, the sketch must define where, when and how the customer will realize the usefulness. And to force distillation blinding, demand they use a fat, felt tip marker. With this clarity, leaders with good judgement can use their judgement effectively. Good questions flow freely. Does every user of a hammer need this? Can a left-handed customer use the thumb guard? How does it stay on? Doesn’t it get in the way? Where do they put it when they’re done? Do they wear it all the time? With this clarity, the questions are so good there is no escape. If there are holes they will be uncovered.

To create the causes and conditions for innovation, demand a one-page hand sketch of the customer demonstrating the useful novelty.

To be successful, the useful novelty must be sufficiently meaningful that customers pay money for it. The standard revenue projections are presented, but, because there is deep clarity on the novelty and usefulness, there is enough context for good judgement to be effective. What fraction of hammer users hit their thumbs? How often? Don’t they smash their fingers too? Why no finger protection? Because of the clarity, there is no escape.

To create the causes and conditions, use the deep clarity to push hard on buying decisions and revenue projections.

The novel, useful, successful framework is a straightforward way to decide if the project portfolio will meet growth objectives. It demands a clear understanding of the newness created by the project but, in return, provides context needed to use good judgement. In that way, because projects cannot start without passing the usefulness and successfulness tests, resources are not allocated to unworthy projects.

But while clarity and this level of depth is a good start, it’s not enough. It’s time for a deeper dive. The project must distill the novelty into a conflict diagram, another one-pager like the others, but deeper. Like problem definition on steroids, a conflict must be defined in space – between two things (thumb and face of hammer head) – and time (just as the hammer hits thumb). With that, leaders can ask before-during-after questions. Why not break the conflict before it happens by making a holding mechanism that keeps the thumb out of the strike zone? Are you sure you want to solve it during the conflict time (when the hammer hits thumb)? Why not solve it after the fact by selling ice packs for their swollen thumbs?

But, more on the conflict domain at another time.

For now, use novel, useful, successful to stop bad projects and start good ones.

Image credit – Natashi Jay

Understanding the trajectory of the competitive landscape

If you want to gain ground on your competition you’ve first got to know where things stand. Where are their advantages? Where are your advantages? Where is there parity? To quickly understand the situations there are three tricks: stay at a high level, represent the situation in a clear way and, where possible, use public information from their website.

If you want to gain ground on your competition you’ve first got to know where things stand. Where are their advantages? Where are your advantages? Where is there parity? To quickly understand the situations there are three tricks: stay at a high level, represent the situation in a clear way and, where possible, use public information from their website.

A side-by-side comparison of the two companies’ products is the way to start. Create a common set of axes with price running south to north and performance (or output) running west to east. Make two copies and position them side-by-side on the page – yours on the left and theirs directly opposite on the right. Go to their website (and yours) and make a list of every product, its price and its output. (For prices of their products you may have to engage your sales team and your customers.) For each of your products place a symbol (the company logo) on your performance-price landscape and do the same for their products on their landscape. It’s now clear who has the most products, where their portfolio outflanks yours and where you outflank them. The clarity and simplicity will help everyone see things as they are – there may be angst but there will be no confusion and no disagreement. The picture is clear. But it’s static.

The areal differences define the gaps to close and the advantages to exploit. Now it’s time to define the momentum and trajectories of the portfolios to add a dynamic element. For your most recent product launch add a one next to its logo, for the second most recent add a two and for the third add three. These three regions of your portfolio are your most recent focus areas. This is your trajectory and this is where you have momentum. Extend and arrow in the direction of your trajectory. If you stay the course, this is where your portfolio will add mass. Do the same for your competitor and compare arrows. You know have a glimpse into the future. Are your arrows pointing in the same directions as theirs? Are they located in the same regions? How would feel if both companies continued on their trajectories? With this addition you have glimpse into the stay-the-course future. But will they stay the course? For that you need to look at the patent landscape.

Do a patent search on their patents and applications over the previous year and represent each with its most descriptive figure. Write a short thematic description for each, group like themes and draw a circle around them. Mark the circle with a one to denote last year’s patents. Repeat the process for two years ago and three years ago and mark each circle accordingly. Now you have objective evidence of the future. You know where they have been working and you know where they want to go. You have more than a glimpse into the future. You know their preferred trajectories. Reconcile their preferred trajectories with their price-performance landscapes and arrows 1, 2 and 3. If their preferred trajectories line up with their product momentum, it’s business as usual for them. If they contradict, they are playing a different game. And because it takes several years for patent applications to publish, they’ve been playing a new game for a while now.

Repeat the process for your patent landscape and flop it onto your performance-price landscape. I’m not sure what you’ll see, but you’ll know it when you see it. Then, compare yours with theirs and you’ll know what the competitive landscape will look like in three years. You may like what you see, or not. But, the picture will be clear. There may be discomfort, but there can be no arguments.

This process can also be used in the acquisition process to get a clear picture a company’s future state. In that way you can get a calibrated view three years into the future and use your crystal ball to adjust your offer price accordingly.

Image credit – Rob Ellis

Learning at the expense of predicting.

When doing new things there is no predictability. There’s speculation, extrapolation and frustration, but no prediction. And the labels don’t matter. Whether it’s called creativity, innovation, discontinuous improvement or disruption there’s no prediction.

When doing new things there is no predictability. There’s speculation, extrapolation and frustration, but no prediction. And the labels don’t matter. Whether it’s called creativity, innovation, discontinuous improvement or disruption there’s no prediction.

The trick in the domain complexity is to make progress without prediction.

The first step is to try to define the learning objective. The learning objective is what you want to learn. And its format is – We want to learn that [fill in the learning objective here]. It’s fastest to tackle one learning objective at a time because small learning objectives are achieved quickly with small experiments. But, it will be a struggle to figure out what to learn. There will be too many learning objectives and none will be defined narrowly. At this stage the fastest thing to do is stop and take a step back.

There’s nothing worse than learning about the wrong thing. And it’s slow. (The fastest learning experiments are the ones that don’t have to be run.) Before learning for the sake of learning, take the necessary time to figure out what to learn. Ask some questions: If it worked could it reinvent your industry? Could it obsolete your best product? Could it cause competitors to throw in the towel? If the answer is no, stop the project and choose one where the answer is yes. Choose a meaningful project, or don’t bother.

First learning objective – We want to learn that, when customers love the new concept, the company will assign appropriate resources to commercialize it. If there’s no committment up front, stop. If you get committment, keep going. (Without upfront buy-in the project relies on speculation, the wicked couple of prediction and wishful thinking.)

Second learning objective – We want to learn that customers love the new concept. This is not “I think customers will love it.” or “Customers may love it.” In the standard learning objective format – We want to learn that [customers love the new concept]. Next comes the learning plan.

What will you build for customers to help them understand the useful novelty of the revolutionary concept? For speed’s sake, build a non-functional prototype that stands for the concept. It’s a thin skin wrapped around an empty box that conveys the essence of the novelty. No skeleton, just skin. And for speed’s sake, show it to fewer customers than you think reasonable. And define the criteria to decide they love it. There’s no trick here. Ask “Do they love it?” and use your best judgement. At this early stage, the answer will be no. But they’ll tell you why they don’t love it, and that’s just the learning you’re looking for.

Use customer input to reformulate the learning objective and build a new prototype and repeat. The key here is to build fast, test fast, learn fast and repeat fast. The art becomes defining the simplest learning objectives, building the simplest prototypes and making decisions with data from the fewest customers.

With complexity and newness prediction isn’t possible. But learning is.

And learning doesn’t have to take a lot of time.

Image credit — John William Waterhouse

Why not start?

It doesn’t matter where the journey ends, as long as it starts.

It doesn’t matter where the journey ends, as long as it starts.

After starting, don’t fixate on the destination, focus on how you get there.

A long project doesn’t get shorter until you start. Neither does a short one.

Start under the radar.

When a project is too big to start, tear off a bite-sized chunk, chew it and swallow.

Sometimes slower is faster, but who cares. You’ve started.

If you can’t start, help some else start. You’ll both be better for it.

Fear blocks starting. But if you’re going to be afraid, you might as well start.

The only way to guarantee failure is to fail to start.

After you start, tell your best friend.

When starting, be clear on your location and less clear on the destination.

You either start or you don’t. With starting, there’s no partial credit.

Don’t start unless you’re going to finish.

Starting is scary, right up until you start.

The best way to free up time to start a good project is to stop a bad one.

Sometimes it’s best to stop starting and start finishing.

You don’t need permission to start. You just need to start.

Start small. If that doesn’t work, start smaller.

In the end, starting starts with starting.

And if you don’t start you can’t finish.

Image credit — jakeandlindsay

Moving Away from Best Practices

If the work is new, there is no best practice.

If the work is new, there is no best practice.

When you read the best books you’ll understand what worked in situations that are different than yours. When you read the case studies you’ll understand how one company succeeded in a way that won’t work in yours. The best practices in the literature worked in a different situation, in a different time and a under different cultural framework. They won’t work best for you.

Just because a practice worked last time doesn’t mean it’s a best practice this time. More strongly, just because it worked last time doesn’t mean it was best last time. There may have been a better way.

When a problem has high urgency it should be solved in a fast way, but if urgency is low, the problem should be solved in an efficient way. Which way is best? If the consequences of getting it wrong are severe, analyses and parallel solutions are skillful, but if it’s not terribly important to get it right, a lower cost way is better. But is either the best way?

The best practices found in books are usually described a high level of abstraction using action words, block diagrams and arrows. And when described at such a high level, they’re not actionable. You may know all the major steps, but you won’t know how each step should be done. And if the detail is provided, the context of your situation is different and the prescriptive steps don’t apply.

Instead of best practices, think effective practices. Effective because the people doing the work can do it effectively. Effective because it fits with the capability and capacity of the people doing the work. Effective because it meshes with existing processes and projects. Effective because it fits with your budget, timeline and risk profile. Effective because it fits with your company values.

Because all our systems are people systems, there are no best practices.

Rule 1: Don’t start a project until you finish one.

One of the biggest mistakes I know is to get too little done by trying to do too much.

One of the biggest mistakes I know is to get too little done by trying to do too much.

In high school we got too comfortable with partial credit. Start the problem the right way, make a few little mistakes and don’t actually finish the problem – 50% credit. With product development, and other real life projects, there’s no partial credit. A project that’s 90% done is worth nothing. All the expense with none of the benefit. Don’t launch, don’t sell. No finish, no credit.

But our ill-informed focus on productivity has hobbled us. Because we think running projects in parallel is highly efficient, we start too many projects. This glut does nothing more than slow down all the other projects in the pipeline. It’s like we think queuing theory isn’t real because we don’t understand it. But to be fair to queuing and our stockholders, queuing theory is real.

Queues are nothing more than a collection of wayward travelers waiting in line for a shared resource. Wait in line for fast food, you’re part of a queue. Wait in line for a bank teller (a resource,) you’re queued up. Wait in line to board a plane, you’re waiting in a queue. But the name isn’t important. Line or queue, what matters is how long you wait.

Lines are queues and queues are lines, but the math behind them is funky. From firsthand experience we know longer queues mean longer wait times. And if the cashier isn’t all that busy (in queuing language – the utilization of the resource is low) the wait time isn’t all that bad and it increases linearly with the number of people (or jobs) in the queue. When the shared resource (cashier) isn’t highly utilized (not all that busy), add a few more shoppers per hour and wait times increase proportionately. But, and this is a big but, if the resource busy more than 80% of the time, increasing the number of shoppers increases the wait time astronomically (or exponentially.) When shoppers arrive in front of the cashier just a bit more often, wait times can double or triple or more.

For wait times, the math of queueing theory says one plus one equals two and one plus one plus one equals seven. Wait times increase linearly right up until they explode. And when wait times explode, projects screech to a halt. And because there’s no partial credit, it’s a parking lot of projects without any of the profit. And what’s the worst thing to do when projects aren’t finishing quickly enough? Start more projects. And what do we do when projects aren’t launching quickly enough? Start more projects.

When there’s no partial credit, instead of efficiency it’s better to focus on effectiveness. Instead of counting the number of projects running in parallel (efficiency,) count the number of projects that have finished (effectiveness.) To keep wait times reasonable, fiercely limit the amount of projects in the system. And there’s a simple way to do that. Figure out the sweet spot for your system, say, three projects in parallel, and create three project “tickets.” Give one ticket to the three active projects and when the project finishes, the project ticket gets assigned to the next project so it can start. No project can start without a ticket. No ticket, no project.

This simple ticket system caps the projects, or work in process (WIP,) so shared resources are utilized below 80% and wait times are low. Projects will sprint through their milestones and finish faster than ever.

By starting fewer projects you’ll finish more. Stop starting and start finishing.

Image credit – Fred Moore

Always Tight on Time

There always far more tasks than there is time. Same for vacations and laundry. And that’s why it’s important to learn when-and how-to say no. No isn’t a cop-out. No is ownership of the reality we can’t do everything. The opposite of no isn’t maybe; the opposite of no is yes while knowing full well it won’t get done. Where the no-in-the-now is skillful, the slow no is unskillful.

There always far more tasks than there is time. Same for vacations and laundry. And that’s why it’s important to learn when-and how-to say no. No isn’t a cop-out. No is ownership of the reality we can’t do everything. The opposite of no isn’t maybe; the opposite of no is yes while knowing full well it won’t get done. Where the no-in-the-now is skillful, the slow no is unskillful.

When you know the work won’t get done and when you know the trip to the Grand Canyon won’t happen, say no. Where yes is the instigator of dilution, no is the keystone of effectiveness.

And once it’s yes, Parkinson’s law kicks you in the shins. It’s not Parkinson’s good idea or Parkinson’s conjecture – it’s Parkinson’s law. And it’s a law is because the work does, in fact, always fill the time available for its completion. If the work fills the time available, it makes sense to me to define the time you’ll spend on a task before starting the task. More important tasks are allocated more time, less important tasks get less and the least important get a no-in-the-now. To beat Parkinson at his own game, use a timer.

Decide how much time you want to spend on a task. Then, to improve efficiency, divide by two. Set a countdown timer (I like E.gg Timer) and display it in the upper right corner of your computer screen. (As I write this post, my timer has 1:29 remaining.) As the timer counts down you’ll converge on completeness.

80% right, 100% done is a good mantra.

I guess I’m done now.

Image credit — bruno kvot

Stopping Before Starting

Whether it’s strategic planning or personal planning, work always outstrips capacity. And whether it’s corporate growth or personal improvement, there’s always a desire to do more. But the more-with-less and it’s-never-good-enough paradigms have overfilled everyone’s plates, and there’s no room for more. There is no more time to double-book and there are no more resources to double-dip. Though the growth-on-all-fronts will not stop, more is not the answer.

Whether it’s strategic planning or personal planning, work always outstrips capacity. And whether it’s corporate growth or personal improvement, there’s always a desire to do more. But the more-with-less and it’s-never-good-enough paradigms have overfilled everyone’s plates, and there’s no room for more. There is no more time to double-book and there are no more resources to double-dip. Though the growth-on-all-fronts will not stop, more is not the answer.

Growth objectives and BHAGs are everywhere and there are more than too many good ideas to try. And with salary increases and incentive compensation tied to performance and the accountability movement liberally slathered over the organization, there’s immense pressure to do more. There’s so much pressure to do more and so little tolerance for a resource-constrained “No, we can’t do that.” the people that do the work no longer no longer respond truthfully to the growth edict. They are tired of fighting for timelines driven by work content and project pipelines based on resources. Instead, they say yes to more, knowing full well that no will come later in the form of slipped timelines, missed specifications and disgruntled teams.

Starting is easy, but starting requires resources. And with all resources over-booked for the next three years, starting must start with stopping. Here’s a rule for our environment of fixed resources: no new projects without stopping an existing one. Finishing is the best form of stopping, but mid-project cancellation is next best. Stopping is much more difficult than starting because stopping breaks commitments, changes compensation and changes who has power and control. But in the age of growth and accountability, stopping before starting is the only way.

Stopping doesn’t come easy, so it’s best to start small. The best place to start stopping is your calendar. Look out three weeks and add up the hours of your standing meetings. Write that number down and divide by two. That’s your stopping target.

For meetings you own, cancel all the status meetings. Instead of the status meeting write short status updates. For your non-status meetings, reduce their duration by half. Write down the hours of meetings you stopped. For meetings you attend, stop attending all status meetings. (If there’s no decision to be made at the meeting, it’s a status meeting.) Read the status updates sent out by the meeting owner. Write down the hours of meetings you stopped attending and add it to the previous number.

If you run meetings 3 hours a week and attend others meetings 5 hours per week, that’s 8 hours of meetings, leaving 32 for work. If you hit your stopping target you free up 4 hours per week. It doesn’t sound meaningful, but it is. It’s actually a 12% increase in work time. [(4÷32) x 100% = 12.5%]

The next step is counter intuitive – for every hour you free up set up an hour of recurring meetings with yourself. (4 hours stopped, 4 hours started.) And because these new meetings with yourself must be used for new work, 12% of your time must be spent doing new work

The stopping mindset doesn’t stop at meetings. Allocate 30 minutes a week in one of your new meetings (you set the agenda for them) to figure how to stop more work. Continue this process until you’ve freed up 20% of your time for new work.

More isn’t the answer. Stopping is.

Image credit – Craig Sefton

Established companies must be startups, and vice versa.

For established companies, when times are good, it’s not the right time to try something new – the resources are there but the motivation is not; and when times are tough it’s also the wrong time to try something new – the motivation is there but the breathing room is not. There are an infinite number of scenarios, but for the established company it’s never a good time to try something new.

For established companies, when times are good, it’s not the right time to try something new – the resources are there but the motivation is not; and when times are tough it’s also the wrong time to try something new – the motivation is there but the breathing room is not. There are an infinite number of scenarios, but for the established company it’s never a good time to try something new.

For startup companies, when times are good, it’s the right time to try something new – the resources are there and so is the motivation; and when times are tough it’s also the right time to try something new – the motivation is there and breathing room is a sign of weakness. Again, the scenarios are infinite, but for the startup is always a good time to try something new.

But this is not a binary world. To create new markets and new customers, established companies must be a little bit startup, and to scale, startups must ultimately be a little bit established. This ambidextrous company is good on paper, but in the trenches it gets challenging. (Read Ralph Ohr for an expert treatment.) The establishment regime never wants to do anything new and the startup regime always wants to. There’s no middle ground – both factions judge each other through jaded lenses of ROI and learning rate and mutual misunderstanding carries the day. Trouble is, all companies need both – established companies need new markets and startups need to scale. But it’s more complicated than that.

As a company matures the balance of power should move from startup to established. But this tricky because the one thing power doesn’t like to do is move from one camp to another. This is the reason for the “perpetual startup” and this is why it’s difficult to scale. As the established company gets long in the tooth the balance of power should move from the establishment to the startup. But, again, power doesn’t like to change teams, and established companies squelch their fledgling startup work. But it’s more complicated, still.

The competition is ever-improving, the economy is ever-changing and the planet is ever-warming. New technologies come on-line, and new business models test the waters. Some work, some don’t. Huge companies buy startups just to snuff them out and established companies go away. The environment is ever-changing on all fronts. And the impermanence pushes and pulls on the pendulum of power dynamics.

All companies want predictability, but they’ll never have it. All growth models are built on rearward-looking fundamentals and forward-looking conjecture. Companies will always have the comfort of their invalid models, but will never the predictability they so desperately want. Instead of predictability, companies would be better served by a strong sense of how it wants to go about its business and overpowering genetics of adaptability.

For a strong definition of how to go about business, a simple declaration does nicely. “We want to spend 80% of our resources on established-company work and 20% on startup-company work.” (Or 90-10, or 95-5.) And each quarter, the company measures itself against its charter, and small changes are made to keep things on track. Unless, of course, if the environment changes or the business model runs out of gas. And then the company adapts. It changes its approach and it’s projects to achieve its declared 80-20 charter, or, changes the charter altogether.

A strong charter and adaptability don’t seem like good partners, but they are. The charter brings focus and adaptability brings the change necessary to survive in an every-changing environment. It’s not easy, but it’s effective. As long as you have the right leaders.

Image credit – Rick Abraham1

When on vacation, be on vacation.

As vacation approaches the work days drag. Sure you’re excited about the future, but when compared to the upcoming pleasantness, the daily grind feels more like a prison. Anticipating a good time in the future rips you from the present moment and puts you in a place you’d rather be. And when you don’t want to be where you are, wherever you are becomes your jail cell.

As vacation approaches the work days drag. Sure you’re excited about the future, but when compared to the upcoming pleasantness, the daily grind feels more like a prison. Anticipating a good time in the future rips you from the present moment and puts you in a place you’d rather be. And when you don’t want to be where you are, wherever you are becomes your jail cell.

Mid-way through vacation, as the work days approach, you push yourself into the future and anticipate the stress and anxiety of the work day. Though vacation should be fun, the stress around the workday and the impending loss of vacation prevent your full engagement in the perfect now. I’m not sure why, but for some reason your brain doesn’t want to be on vacation with you. It’s difficult to think of your perfect vacation as your jail cell, but while your brain is disembodied, I think it is.

And when vacation is over and you return to work, it’s pretty clear you’re back in jail. You put yourself back in the past of your wonderful vacation; compare your cubicle your previous poshness; and make it clear to yourself that you’d rather be somewhere else. And the better your vacation, the longer your jail time.

But it’s easier to see how we use unpleasant situations to build our jail cells. Our aversion to uncomfortable situations pushes us into the past to beat ourselves up over uncontrollable factors we think we should have recognized and controlled. We turn a simple unpleasant situation into a jail cell of self-judging. Or, we push ourselves into the future and generate anxiety around a sea of catastrophic consequences, none of which will happen. Instead of building jails, it’s far more effective to let ourselves feel the unpleasantness for what it is (the result of thoughts of our own making) and let it dissipate on its own.

The best way to become a jail breaker is to start with awareness – awareness your mind has left the present moment. When you’re on vacation, be on vacation. And when you’re in the middle of an unpleasant situation, sit right there in the middle of the unpleasant situation. (No one has ever died from an unpleasant situation.) And, as a skillful jail breaker, when you realize your mind is in the past or future, don’t judge yourself, praise yourself for recognizing your mind’s unintended time travel and get back to your vacation.

But this is more than a recipe for better vacations. It’s a recipe for better relationships and better work. You can be all-in with the people you care about and you can be singularly focused on the most challenging work. When someone is standing in front of you and you give them 100% of your attention, your relationship with them improves. And when you give a problem 100% of your attention, it gets solved.

Think about the triggers that pull and push you out of the present moment (the dings of texts, the beeps of emails, or the buzzes of push notifications) and get rid of them. At least while you’re on vacation.

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski