Archive for the ‘How To’ Category

How to Choose the Best Idea

We have too many ideas, but too few great ones. We don’t need more ideas, we need a way to choose the best one or two ideas and run them to ground.

We have too many ideas, but too few great ones. We don’t need more ideas, we need a way to choose the best one or two ideas and run them to ground.

Before creating more ideas, make a list of the ones you already have. Put them in two boxes. In Box 1, list the ideas without a video of a functional prototype in action. In Box 2, list the ideas that have a video showing a functional prototype demonstrating the idea in action. For those ideas with a functional prototype and no video, put them in Box 1.

Next, throw away Box 1. If it’s not important enough to make a crude physical prototype and create a simple video, the idea isn’t worth a damn. If someone isn’t willing to carve out the time to make a physical prototype, there’s no emotional energy behind the idea and it should be left to die. And when people complain that it’s unfair to throw away all those good ideas in Box 1, tell them it’s unfair to spend valuable resources talking about ideas that aren’t worthy. And suggest, if they want to have a discussion about an idea, they should build a physical prototype and send you the video. Box 2, or bust.

Next, get the band together and watch the short videos in Box 2, and, as a group, put them in two boxes. In Box 3, put the videos without customers actively using the functional prototype. In Box 4, put the videos with customers actively using the functional prototype.

Next, throw way Box 3. If it’s not important enough to make a trip to an important customer and create a short video, the idea isn’t worth a damn. If you’re not willing to put yourself out there and take the idea to an important customer, the idea is all fizzle and no sizzle. Meaningful ideas take immense personal energy to run through the gauntlet, and without a video of a customer using the functional prototype, there’s not enough energy behind it. And when everyone argues that Box 3 ideas are worth pursuing, tell them to pursue a video showing a most important customer demonstrating the functional prototype.

Next, get the band back together to watch the Box 4 videos. Again, put the videos in two boxes. In Box 5 put the videos where the customer didn’t say what they liked and how they’d use it. In Box 6, put the videos where the customer enthusiastically said what they liked and how they’ll use it.

Next, throw away Box 5. If the customer doesn’t think enough about the prototype to tell you how they’ll use it, it’s because they don’t think much of the idea. And when the group says the customer is wrong or the customer doesn’t understand what the prototype is all about, suggest they create a video where a customer enthusiastically explains how they’d use it.

Next, get the band back in the room and watch the Box 6 videos. Put them in two boxes. In Box 7, put the videos that won’t radically grow the top line. In Box 8, put the videos that will radically grow the top line. Throw away Box 7.

For the videos in Box 8, rank them by the amount of top line growth they will create. Put all the videos back into Box 8, except the video that will create the most top line growth. Do NOT throw away Box 8.

The video in your hand IS your company’s best idea. Immediately charter a project to commercialize the idea. Staff it fully. Add resources until adding resources doesn’t no longer pulls in the launch. Only after the project is fully staffed do you put your hand back into Box 8 to select the next best idea.

Continually evaluate Boxes 1 through 8. Continually throw out the boxes without the right videos. Continually choose the best idea from Box 8. And continually staff the projects fully, or don’t start them.

Image credit – joiseyshowaa

What’s your problem?

If you don’t have a problem, you’ve got a big problem.

If you don’t have a problem, you’ve got a big problem.

It’s important to know where a problem happens, but also when it happens.

Solutions are 90% defining and the other half is solving.

To solve a problem, you’ve got to understand things as they are.

Before you start solving a new problem, solve the one you have now.

It’s good to solve your problems, but it’s better to solve you customers’ problems.

Opportunities are problems in sheep’s clothing.

There’s nothing worse than solving the wrong problem – all the cost with none of the solution.

When you’re stumped by a problem, make it worse then do the opposite.

With problem definition, error on the side of clarity.

All problems are business problems, unless you care about society’s problems.

Odds are, your problem has been solved by someone else. Your real problem is to find them.

Define your problem as narrowly as possible, but no narrower.

Problems are not a sign of weakness.

Before adding something to solve the problem, try removing something.

If your problem involves more than two things, you have more than one problem.

The problem you think you have is never the problem you actually have.

Problems can be solved before, during or after they happen and the solutions are different.

Start with the biggest problem, otherwise you’re only getting ready to solve the biggest problem.

If you can’t draw a closeup sketch of the problem, you don’t understand it well enough.

If you have an itchy backside and you scratch you head, you still have an itch. And it’s the same with problems.

If innovation is all about problem solving and problem solving is all about problem definition, well, there you have it.

Image credit – peasap

Mapping the Future with Wardley Maps

How do you know when it’s time to reinvent your product, service or business model? If you add ten units of energy and you get less in return than last time, it’s time to work in new design space. If improvement in customer goodness (e.g., miles per gallon in a car) has slowed or stopped, it’s time to seek a new fuel source. If recent patent filings are trivial enhancements that can be measured only with a large sample sizes and statistical analysis, the party is over.

How do you know when it’s time to reinvent your product, service or business model? If you add ten units of energy and you get less in return than last time, it’s time to work in new design space. If improvement in customer goodness (e.g., miles per gallon in a car) has slowed or stopped, it’s time to seek a new fuel source. If recent patent filings are trivial enhancements that can be measured only with a large sample sizes and statistical analysis, the party is over.

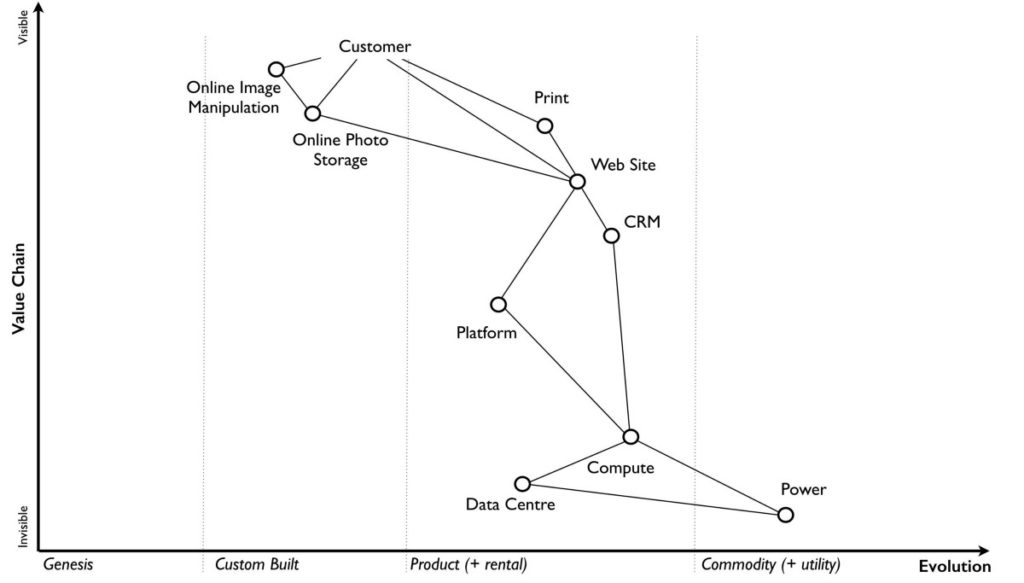

When there’s so many new things to work on, how do you choose the next project? When you’re lost, you look at a map. And when there is no map, you make one. The first bit of work is defined by the holes in the first revision of your map. And once the holes are filled and patched, the next work emerges from the map itself. And, in a self-similar way, the next work continually emerges from the previous work until the project finishes.

But with so much new territory, how do you choose the right new territory to map? You don’t. Before there’s a need to map new territory, you must map the current territory. What you’ll learn is there are immature areas that, when made mature, will deliver new value to customers. And you’ll also learn the mature areas that must be blown up and replaced with infant solutions that will ultimately create the next evolution of your business. And as you run thought experiments on your map – projecting advancements on the various elements – the right new territory will emerge. And here’s a hint – the right new solutions will be enabled by the newly matured elements of the map.

But how do you predict where the right new solutions will emerge? I can’t tell you that. You are the experts, not me. All I can say is, make the maps and you’ll know.

And when I say maps, I mean Wardely Maps – here’s a short video (go to 4:13 for the juicy bits).

Image credit – Simon Wardley

Innovation – Words vs. Actions

Innovation isn’t a thing in itself. Companies need to meet their growth objectives and innovation is the word experts use to describe the practices and behaviors they think will maximize the likelihood of meeting those growth objectives. Innovation is a catchword phrase that has little to no meaning. Don’t ask about innovation, ask how to meet your business objectives. Don’t ask about best practices, ask how has your company been successful and how to build on that success. Don’t ask how the big companies have done it – you’re not them. And, the behaviors of the successful companies are the same behaviors of the unsuccessful companies. The business books suffer from selection bias. You can’t copy another company’s innovation approach. You’re not them. And your project is different and so is the context.

Innovation isn’t a thing in itself. Companies need to meet their growth objectives and innovation is the word experts use to describe the practices and behaviors they think will maximize the likelihood of meeting those growth objectives. Innovation is a catchword phrase that has little to no meaning. Don’t ask about innovation, ask how to meet your business objectives. Don’t ask about best practices, ask how has your company been successful and how to build on that success. Don’t ask how the big companies have done it – you’re not them. And, the behaviors of the successful companies are the same behaviors of the unsuccessful companies. The business books suffer from selection bias. You can’t copy another company’s innovation approach. You’re not them. And your project is different and so is the context.

With innovation, the biggest waste of emotional energy is quest for (and arguments around) best practices. Because innovation is done in domains of high ambiguity, there can be no best practices. Your project has no similarity with your previous projects or the tightest case studies in the literature. There may be good practice or emergent practice, but there can be no best practice. When there is no uncertainty and no ambiguity, a project can use best practices. But, that’s not innovation. If best practices are a strong tenant of your innovation program, run away.

The front end of the innovation process is all about choosing projects. If you want to be more innovative, choose to work on different projects. It’s that simple. But, make no mistake, the principle may be simple the practice is not. Though there’s no acid test for innovation, here are three rules to get you started. (And if you pass these three tests, you’re on your way.)

- If you’ve done it before, it’s not innovation.

- If you know how it will turn out, it’s not innovation.

- If it doesn’t scare the hell out of you, it’s not innovation.

Once a project is selected, the next cataclysmic waste of time is the construction of a detailed project plan. With a well-defined project, a well-defined project plan is a reasonable request. But, for an innovation project with a high degree of ambiguity, a well-defined project plan is impossible. If your innovation leader demands a detailed project plan, it’s usually because they are used running to well-defined continuous improvement projects. If for your innovation projects you’re asked for a detailed project plan, run away.

With innovation projects, you can define step 1. And step 2? It depends. If step 1 works, modify step 2 based on the learning and try step 2. And if step 1 doesn’t work, reformulate step 1 and try again. Repeat this process until the project is complete. One step at a time until you’re done.

Innovation projects are unpredictable. If your innovation projects require hard completion dates, run away.

Innovation projects are all about learning and they are best defined and managed using Learning Objectives (LOs). Instead of step 1 and step 2, think LO1 and LO2. Though there’s little written about LOs, there’s not much to them. Here’s the taxonomy of a LO: We want to learn if [enter what you want to learn]. Innovation projects are nothing more than a series of interconnected LOs. LO2 may require the completion of LO1 or L1 and LO2 could be done in parallel, but that’s your call. Your project plan can be nothing more than a precedence diagram of the Learning Objectives. There’s no need for a detailed Gantt chart. If you’re asked for a detailed Gantt chart, you guessed it – run away.

The Learning Objective defines what you learn, how you want to learn, who will do the learning and when they want to do it. The best way to track LOs is with an Excel spreadsheet with one tab for each LO. For each LO tab, there’s a table that defines the actions, who will do them, what they’ll measure and when they plan to get the actions done. Since the tasks are tightly defined, it’s possible to define reasonable dates. But, since there can be a precedence to the LOs (LO2 depends on the successful completion of LO1), LO2 can be thought of a sequence of events that start when LO1 is completed. In that way, an innovation project can be defined with a single LO spreadsheet that defines the LOs, the tasks to achieve the LOs, who will do the tasks, how success will be determined and when the work will be done. If you want to learn how to do innovation, learn how to use Learning Objectives.

There are more element of innovation to discuss, for example how to define customer segments, how to identify the most important problems, how to create creative solutions, how to estimate financial value of a project and how to go to market. But, those are for another post.

Until then, why not choose a project that scares you, define a small set of Learning Objectives and get going?

Image credit – JD Hancock

If you want to learn, define a learning objective.

Innovation is all about learning. And if the objective of innovation is learning, why not start with learning objectives?

Innovation is all about learning. And if the objective of innovation is learning, why not start with learning objectives?

Here’s a recipe for learning: define what you want to learn, figure how you want to learn, define what you’ll measure, work the learning plan, define what you learned and repeat.

With innovation, the learning is usually around what customers/users want, what new things (or processes) must be created to satisfy their needs and how to deliver the useful novelty to them. Seems pretty straightforward, until you realize the three elements interact vigorously. Customers’ wants change after you show them the new things you created. The constraints around how you can deliver the useful novelty (new product or service) limit the novelty you can create. And if the customers don’t like the novelty you can create, well, don’t bother delivering it because they won’t buy it.

And that’s why it’s almost impossible to develop a formal innovation process with a firm sequence of operations. Turns out, in reality the actual process looks more like a fur ball than a flow chart. With incomplete knowledge of the customer, you’ve got to define the target customer, knowing full-well you don’t have it right. And at the same time, and, again, with incomplete knowledge, you’ve got to assume you understand their problems and figure out how to solve them. And at the same time, you’ve got to understand the limitations of the commercialization engine and decide which parts can be reused and which parts must be blown up and replaced with something new. All three explore their domains like the proverbial drunken sailor, bumping into lampposts, tripping over curbs and stumbling over each other. And with each iteration, they become less drunk.

If you create an innovation process that defines all the if-then statements, it’s too complicated to be useful. And, because the if-thens are rearward-looking, they don’t apply the current project because every innovation project is different. (If it’s the same as last time, it’s not innovation.) And if you step up the ladder of abstraction and write the process at a high level, the process steps are vague, poorly-defined and less than useful. What’s a drunken sailor to do?

Define the learning objectives, define the learning plan, define what you’ll measure, execute the learning plan, define what you learned and repeat.

When the objective is learning, start with the learning objectives.

Image credit Jean L.

Don’t trust your gut, run the test.

At first glance, it seems easy to run a good test, but nothing can be further from the truth.

At first glance, it seems easy to run a good test, but nothing can be further from the truth.

The first step is to define the idea/concept you want to validate or invalidate. The best way is to complete one of these two sentences: I want to learn that [type your idea here] is true. Or, I want to learn that [enter your idea here] is false.

Next, ask yourself this question: What information do I need to validate (or invalidate) [type your idea here]? Write down the information you need. In the engineering domain, this is straightforward: I need the temperature of this, the pressure of that, the force generated on part xyz or the time (in seconds) before the system catches fire. But for people-related ideas, things aren’t so straightforward. Some things you may want to know are: how much will you pay for this new thing, how many will you buy, on a scale of 1 to 5 how much do you like it?

Now the tough part – how will you judge pass or fail? What is the maximum acceptable temperature? What is the minimum pressure? What is the maximum force that can be tolerated? How many seconds must the system survive before catching fire? And for people: What is the minimum price that can support a viable business? How many must they buy before the company can prosper? And if they like it at level 3, it’s a go. And here’s the most importance sentence of the entire post:

The decision criteria must be defined BEFORE running the test.

If you wait to define the go/no-go criteria until after you run the test and review the data, you’ll adjust the decision criteria so you make the decision you wanted to make before running the test. If you’re not going to define the decision criteria before running the test, don’t bother running the test and follow your gut. Your decision will be a bad one, but at least you’ll save the time and money associated with the test.

And before running the test, define the test protocol. Think recipe in a cookbook: a pinch of this, a quart of that, mix it together and bake at 350 degrees Fahrenheit for 40 minutes. The best protocols are simple and clear and result in the same sequence of events regardless of who runs the test. And make sure the measurement method is part of the protocol – use this thermocouple, use that pressure gauge, use the script to ask the questions about price and the number they’d buy.

And even with all this rigor, good judgement is still part of the equation. But the judgment is limited to questions like: did we follow the protocol? Did the measurement system function properly? Do the initial assumptions still hold? Did anything change since we defined the learning objective and defined the test protocol?

To create formal learning objectives, to write well-defined test protocols and to formalize the decision criteria before running the test require rigor, discipline, time and money. But, because the cost of making a bad decision is so high, the cost of running good tests is a bargain at twice the price.

Image credit – NASA Goddard Flight Center

It’s time to stretch yourself.

If the work doesn’t stretch you, choose new work. Don’t go overboard and make all your work stretch you and don’t choose work that will break you. There’s a balance point somewhere between 0% and 100% stretch and that balance point is different for everyone and it changes over time. Point is, seek your balance point.

If the work doesn’t stretch you, choose new work. Don’t go overboard and make all your work stretch you and don’t choose work that will break you. There’s a balance point somewhere between 0% and 100% stretch and that balance point is different for everyone and it changes over time. Point is, seek your balance point.

To find the right balance point, start with an assessment of your stretch level. List the number of projects you have and sum the number of major deliverables you’ve got to deliver. If you have more than three projects, you have too many. And if you think you take on more than three because you’re superhuman, you’re wrong. The data is clear – multitasking is a fallacy. If you have four projects you have too many. And it’s the same with three, but you’d think I was crazy if I suggested you limit your projects to two. The right balance point starts with reducing the number of projects you work on.

Now that you eliminated four or five projects and narrowed the portfolio down to the vital two or three, it’s time to list your major deliverables. Take a piece of paper and write them in a column down the left side of the page. And in a column next to the projects, categorize each of them as: -1 (done it before), 0 (done something similar), 1 (new to me), 2 (new to team), 3 (new to company), 5 (new to industry), 11 (new to world).

For the -1s, teach an entry level person how to do it and make sure they do it well. For the 0s, find someone who deserves a growth opportunity and let them have the work. And check in with them to make sure they do a good job. The idea is to free yourself for the stretch work.

For the 1s, find the best person in the team who has done it before and ask them how to do it. Then, do as they suggest but build on their work and take it to the next level.

For the 2s, find the best person in the company who has done it before and ask them how to do it. Then, build on their approach and make it your own.

For the 3s, do your research and find out who in your industry has done it before. Figure out how they did it and improve on their work.

For the 5s, do your research and figure out who has done similar work in another industry. Adapt their work to your application and twist it into something magical.

And for the 11s, they’re a special project category that live in rarified air and deserve a separate blog post of their own.

Start with where you are – evaluate your existing deliverables, cull them to a reasonable workload and assess your level of stretch. And, where it makes sense, stop doing work you’ve done before and start doing work you haven’t done yet. Stretch yourself, but be reasonable. It’s better to take one bite and swallow than take three and choke.

Image credit – filtran

The Evolution of New Ideas

Before there is something new to see, there is just a good idea worthy of a prototype. And before there can be good ideas there are a whole flock of bad ones. And until you have enough self confidence to have bad ideas, there is only the status quo. Creating something from nothing is difficult.

Before there is something new to see, there is just a good idea worthy of a prototype. And before there can be good ideas there are a whole flock of bad ones. And until you have enough self confidence to have bad ideas, there is only the status quo. Creating something from nothing is difficult.

New things are new because they are different than the status quo. And if the status quo is one thing, it’s ruthless in desire to squelch the competition. In that way, new ideas will get trampled simply based on their newness. But also in that way, if your idea gets trampled it’s because the status quo noticed it and was threatened by it. Don’t look at the trampling as a bad sign, look at it as a sign you are on the right track. With new ideas there’s no such thing as bad publicity.

The eureka moment is a lie. New ideas reveal themselves slowly, even to the person with the idea. They start as an old problem or, better yet, as a successful yet tired solution. The new idea takes its first form when frustration overcomes intellectual inertia a strange sketch emerges on the whiteboard. It’s not yet a good idea, rather it’s something that doesn’t make sense or doesn’t quite fit.

The idea can mull around as a precursor for quite a while. Sometimes the idea makes an evolutionary jump in a direction that’s not quite right only to slither back to it’s unfertilized state. But as the environment changes around it, the idea jumps on the back of the new context with the hope of evolving itself into something intriguing. Sometimes it jumps the divide and sometimes it slithers back to a lower energy state. All this happens without conscious knowledge of the inventor.

It’s only after several mutations does the idea find enough strength to make its way into a prototype. And now as a prototype, repeats the whole process of seeking out evolutionary paths with the hope of evolving into a product or service that provides customer value. And again, it climbs and scratches up the evolutionary ladder to its most viable embodiment.

Creating something new from scratch is difficult. But, you are not alone. New ideas have a life force of their own and they want to come into being. Believe in yourself and believe in your ideas. Not every idea will be successful, but the only way to guarantee failure is to block yourself from nurturing ideas that threaten the status quo.

Image credit – lost places

A Barometer for Uncertainty

Novelty, or newness, can be a great way to assess the status of things. The level of novelty is a barometer for the level of uncertainty and unpredictability. If you haven’t done it before, it’s novel and you should expect the work to be uncertain and unpredictable. If you’ve done it before, it’s not novel and you should expect the work to go as it did last time. But like the barometer that measures a range of atmospheric pressures and gives an indication of the weather over the next hours, novelty ranges from high to low in small increments and so does the associated weather conditions.

Novelty, or newness, can be a great way to assess the status of things. The level of novelty is a barometer for the level of uncertainty and unpredictability. If you haven’t done it before, it’s novel and you should expect the work to be uncertain and unpredictable. If you’ve done it before, it’s not novel and you should expect the work to go as it did last time. But like the barometer that measures a range of atmospheric pressures and gives an indication of the weather over the next hours, novelty ranges from high to low in small increments and so does the associated weather conditions.

Barometers have a standard scale that measures pressure. When the summer air is clear and there are no clouds, the atmospheric pressure is high and on the rise and you should put on sun screen. When it’s hurricane season and super-low system approaches, the drops to the floor and you should evacuate. The nice thing about barometers is they are objective. On all continents, they can objectively measure the pressure and display it. No judgement, just read the scale. And regardless of the level of pressure and the number of times they measure it, the needle matches the pressure. No Kentucky windage. But novelty isn’t like that.

The only way to predict how things will go based on the level of novelty is to use judgement. There is no universal scale for novelty that works on all projects and all continents. Evaluating the level of novelty and predicting how the projects will go requires good judgement. And the only way to develop good judgment is to use bad judgment until it gets better.

All novelty isn’t created equal. And that’s the trouble. Some novelty has a big impact on the weather and some doesn’t. The trick is to know the difference. And how to tell the difference? If when you make a change in one part of the system (add novelty) and the novelty causes a big change in the function or operation of the system, that novelty is important. The system is telling you to use a light hand on the tiller. If the novelty doesn’t make much difference in system performance, drive on. The trick is to test early and often – simple tests that give thumbs-up or thumbs-down results. And if you try to run a test and you can’t get the test to run at all, there’s a hurricane is on the horizon.

When the work is new, you don’t really know which novelty will bite you. But there’s one rule: all novelty will bite you until proven otherwise. Make a list of the novel elements of the and test them crudely and quickly.

Allocating resources as if people and planet mattered.

Business is about allocating resources to achieve business objectives. And for that, the best place to start is to define the business objectives.

Business is about allocating resources to achieve business objectives. And for that, the best place to start is to define the business objectives.

First – what is the timeframe of the business objectives? Well, there are three – short, medium and long. Short is about making payroll, shipping this month’s orders and meeting this year’s sales objectives. Long is about the existence of the company over the next decade and happiness of the people that do the work along the way. And medium – the toughest – is in-between. It’s neither short nor long but bound by both.

Second – define business objectives within the three types: people, planet and profit.

People. Short term: pay them so they can eat, pay the mortgage and fund their retirement, provide healthcare, provide a safe workplace, give them work that fits their strengths and give them time to improve their community. Medium: pay them so they can provide for their family and fund their retirement, provide healthcare, provide a safer workplace, give them work that requires them to grow their strengths and give them time to become community leaders. Long: pay them so they can pay for their kids’ college and know they can safely retire, provide the safest workplace, let them choose their own work, and give them time to grow the next community leaders. And make it easy.

Planet. Short term: teach Life Cycle Assessment, Buddhist Economics and TRIZ and create business metrics for them to flourish. Medium: move from global sourcing to local sourcing, move to local production, move from business models based on non-renewable resources to renewable resources. Long: create new business models that are resource neutral. Longer: create business models that generate excess resources. Longest: teach others.

Profit. Short, medium and long – focus on people and planet and the profits will come. But also focus on creating new value for new customers.

For business objectives, here’s the trick on timeframe – always work short term, always work long term and prioritize medium term.

And for the three types of business objectives, focus on people, planet and creating new value for new customers. Profits are a result.

Image credit – magnetismus

Additive Manufacturing’s Holy Grail

The holy grail of Additive Manufacturing (AM) is high volume manufacturing. And the reason is profit. Here’s the governing equation:

The holy grail of Additive Manufacturing (AM) is high volume manufacturing. And the reason is profit. Here’s the governing equation:

(Price – Cost) x Volume = Profit

The idea is to sell products for more than the cost to make them and sell a lot of them. It’s an intoxicatingly simple proposition. And as long as you look only at the volume – the number of products sold per year – life is good. Just sell more and profits increase. But for a couple reasons, it’s not that simple. First, volume is a result. Customers buy products only when those products deliver goodness at a reasonable price. And second, volume delivers profit only when the cost is less than the price. And there’s the rub with AM.

Here’s a rule – as volume increases, the cost of AM is increasingly higher than traditional manufacturing. This is doubly bad news for AM. Not only is AM more expensive, its profit disadvantage is particularly troubling at high volumes. Here’s another rule – if you’re looking to AM to reduce the cost of a part, look elsewhere. AM is not a bottom-feeder technology.

If you want to create profits with AM, use it to increase price. Use it to develop products that do more and sell for more. The magic of AM is that it can create novel shapes that cannot be made with traditional technologies. And these novel shapes can create products with increased function that demand a higher price. For example, AM can create parts with internal features like serpentine cooling channels with fine-scale turbulators to remove more heat and enable smaller products or products that weigh less. Lighter automobiles get better fuel mileage and customers will pay more. And parts that reduce automobile weight are more valuable. And real estate under the hood is at a premium, and a smaller part creates room for other parts (more function) or frees up design space for new styling, both of which demand a higher price.

Now, back to cost. There’s one exception to cost rule. AM can reduce total product cost if it is used to eliminate high cost parts or consolidate multiple parts into a single AM part. This is difficult to do, but it can be done. But it takes some non-trivial cost analysis to make the case. And, because the technology is relatively new, there’s some aversion to adopting AM. An AM conversion can require a lot of testing and a significant cost reduction to take the risk and make the change.

To win with AM, think more function AND consolidation. More (or new) function to support a higher price (and increase volume) and reduced cost to increase profit per part. Don’t do one or the other. Do both. That’s what GE did with its AM fuel nozzle in their new aircraft engines. They combined 20 parts into a single unit which weighed 25 percent less than a traditional nozzle and was more than five times as durable. And it reduced fuel consumption (more function, higher price).

AM is well-established in prototyping and becoming more established in low-volume manufacturing. The holy grail for AM – high volume manufacturing – will become a broad reality as engineers learn how to design products to take advantage of AM’s unique ability to make previously un-makeable shapes and learn to design for radical part consolidation.

More function AND radical part consolidation. Do both.

Image credit – Les Haines

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski