Archive for the ‘How To’ Category

Meeting Time vs. Thinking Time

How many hours of meetings do you sit through each week? Check your calendar over the previous month and write down that number.

How many hours of meetings do you sit through each week? Check your calendar over the previous month and write down that number.

If you had control over your calendar, would you rather sit through more meetings or fewer?

If you don’t meet enough and need more meetings, I want to work at your company.

If you want fewer, what will you do to change things? Here are two simple things you can try:

- Say no to meetings that have no agenda. Tell them you have a policy to be prepared for all meetings and since you don’t know how to prepare (no agenda!) you’ll sit this one out.

- Say no to meetings where everyone updates each other. Tell them you’ll read the minutes they won’t write.

Check your calendar over the previous month, add the hours you could have saved if you followed the two rules, and divide by four to convert to a weekly average. Write down that number.

How much time do you spend getting ready for meetings each week? Write down that number.

How much time do you spend recovering from meetings each week? (Switching cost is real.) Write down that number.

Now let’s focus on thinking.

How many hours do you think each week? Check your calendar over the previous month, divide by four to convert to a weekly average, and write down that number.

If you had control over your calendar, would you rather think more or less?

If you have too much time to think, I want to work at your company.

If you want to think more, what will you do to change things? Here are two simple things you can try:

- Schedule a one-hour meeting with yourself that recurs weekly. Mark the meeting as “out of office.”

- For the next three weeks, add another recurring meeting with yourself.

And, yes, it’s possible to schedule time to think.

An additional four hours of thinking per week may not sound significant, but it’s probably a 100% increase over your previous weekly average. That’s a big difference especially since everyone else spends most of their time in meetings.

Use the two rules to say no to meetings and you’ll free up a lot of time. And with that freed-up time, you can schedule four hours of thinking time per week.

Why not give it a try? Your career will thank you.

Image credit — Florence Ivy

Improvement In Reverse Sequence

Before you can make improvements, you must identify improvement opportunities.

Before you can make improvements, you must identify improvement opportunities.

Before you can identify improvement opportunities, you must look for them.

Before you can look for improvement opportunities, you must believe improvement is possible.

Before believing improvement is possible, you must admit there’s a need for improvement.

Before you can admit the need for improvement, you must recognize the need for improvement.

Before you can recognize the need for improvement, you must feel dissatisfied with how things are.

Before you can feel dissatisfied with how things are, you must compare how things are for you relative to how things are for others (e.g., competitors, coworkers).

Before you can compare things for yourself relative to others, you must be aware of how things are for others and how they are for you.

Before you can be aware of how things are, you must be calm, curious, and mindful.

Before you can be calm, curious, and mindful, you must be well-rested and well-fed. And you must feel safe.

What choices do you make to be well-rested? How do you feel about that?

What choices do you make to be well-fed? How do you feel about that?

What choices do you make to feel safe? How do you feel about that?

Image credit — Philip McErlean

How To Make Progress

Improvement is progress. Improvement is always measured against a baseline, so the first thing to do is to establish the baseline, the thing you make today, the thing you want to improve. Create an environment to test what you make today, create the test fixtures, define the inputs, create the measurement systems, and write a formal test protocol. Now you have what it takes to quantify an improvement objectively. Test the existing product to define the baseline. No, you haven’t improved anything, but you’ve done the right first thing.

Improvement is progress. Improvement is always measured against a baseline, so the first thing to do is to establish the baseline, the thing you make today, the thing you want to improve. Create an environment to test what you make today, create the test fixtures, define the inputs, create the measurement systems, and write a formal test protocol. Now you have what it takes to quantify an improvement objectively. Test the existing product to define the baseline. No, you haven’t improved anything, but you’ve done the right first thing.

Improving the right thing to make progress. If the problem invalidates the business model, stop what you’re doing and solve it right away because you don’t have a business if you don’t solve it. Any other activity isn’t progress, it’s dilution. Say no to everything else and solve it. This is how rapid progress is made. If the customer won’t buy the product if the problem isn’t solved, solve it. Don’t argue about priorities, don’t use shared resources, don’t try to be efficient. Be effective. Do one thing. Solve it. This type of discipline reduces time to market. No surprises here.

Avoiding improvement of the wrong thing to make progress. For lesser problems, declare them nuisances and permit yourself to solve them later. Nuisances don’t have to be solved immediately (if at all) so you can double down on the most important problems (speed, speed, speed). Demoting problems to nuisances is probably the most effective way to accelerate progress. Deciding what you won’t do frees up resources and emotional bandwidth to make rapid progress on things that matter.

Work the critical path to make progress. Know what work is on the critical path and what is not. For work on the critical path, add resources. Pull resources from non-critical path work and add them to the critical path until adding more slows things down.

Eliminate waiting to make progress. There can be no progress while you wait. Wait for a tool, no progress. Wait for a part from a supplier, no progress. Wait for raw material, no progress. Wait for a shared resource, no progress. Buy the right tools and keep them at the workstations to make progress. Pay the supplier for priority service levels to make progress. Buy inventory of raw materials to make progress. Ensure shared resources are wildly underutilized so they’re available to make progress whenever you need to. Think fire stations, fire trucks, and firefighters.

Help the team make progress. As a leader, jump right in and help the team know what progress looks like. Praise the crudeness of their prototypes to help them make them cruder (and faster) next time. Give them permission to make assumptions and use their judgment because that’s where speed comes from. And when you see “activity” call it by name so they can recognize it for themselves, and teach them how to turn their effort into progress.

Be relentless and respectful to make progress. Apply constant pressure, but make it sustainable and fun.

Image credit — Clint Mason

What It Means To Stand Tall

People try to diminish when they’re threatened.

People try to diminish when they’re threatened.

People are threatened when they think you’re more capable than they are.

When they think less of themselves, they see you as more capable.

There you have it.

When someone doesn’t do what they say and you bring it up to them, there are two general responses. If they forget, they tell you and apologize. If they don’t have a good reason, they respond defensively.

When someone responds defensively, it means they know what they did.

They respond defensively when they know what they did and don’t like what it says about them.

Defensiveness is an admission of guilt.

Defensiveness is an acknowledgment that the ego was bruised.

Defensiveness is a declaration self-worth is insufficient.

People can either stand down or turn it up when defensiveness is called by name.

When people stand down, they demonstrate they have what it takes to own their behavior.

When they turn it up, they don’t.

When people turn their defensiveness into aggressiveness, they’re unwilling to own their behavior because doing so violates their self-image. And that’s why they’re willing to blame you for their behavior.

When you tell someone they didn’t do what they said and they acknowledge their behavior, praise them. Tell them they displayed courage. Thank them.

When you call someone on their defensiveness and they own their behavior, compliment them for their truthfulness. Tell them their truthfulness is a compliment to you. Tell them their truthfulness means you are important to them.

When you call someone on their defensiveness and they respond aggressively, stand tall. Recognize they are threatened and stand tall. Recognize they don’t like what they did and they don’t have what it takes (in the moment) to own their behavior. And stand tall. When they try to blame you, tell them you did nothing wrong. Tell them it’s not okay to try to blame you for their behavior. And stand tall.

It’s not your responsibility to teach them or help them change their behavior. But it is your responsibility to stay in control, to be professional, and to protect yourself.

When you stand tall, it means you know what they’re doing. When you stand tall, it means it’s not okay to behave that way. When you stand tall, it means you are comfortable describing their behavior to those who can do something about it. When you continue to stand tall, you make it clear there is nothing they can do to prevent you from standing tall.

In the future, they may behave defensively and aggressively with others, but they won’t behave that way with you. And maybe that will help others stand tall.

Image credit — Johan Wieland

Wanting What You Have

If you got what you wanted, what would you do?

If you got what you wanted, what would you do?

Would you be happy or would you want something else?

Wanting doesn’t have a half-life. Regardless of how much we have, wanting is always right there with us lurking in the background.

Getting what you want has a half-life. After you get what you want, your happiness decays until what you just got becomes what you always had. I think they call that hedonistic adaptation.

When you have what you always had, you have two options. You can want more or you can want what you have. Which will you choose?

When you get what you want, you become afraid to lose what you got. There’s no free lunch with getting what you want.

When you want more, I can manipulate you. I wouldn’t do that, but I could.

When you want more your mind lives in the future where it tries to get what you want. And lives in the past where it mourns what you did not get or lost.

It’s easier to live in the present moment when you want what you have. There’s no need to craft a plan to get more and no need to lament what you didn’t have.

You can tell when a person wants what they have. They are kind because there’s no need to be otherwise. They are calm because things are good. And they are themselves because they don’t need anything from anyone.

Wanting what you have is straightforward. Whatever you have, you decide that’s what you want. It’s much different than having what you want. Once you have what you want hedonistic adaptation makes you want more, and then it’s time to jump back on the hamster wheel.

Wanting what you have is freeing. Why not choose to be free and choose to want what you have?

Image credit — Steven Guzzardi

Swimming In New Soup

You know the space is new when you don’t have the right words to describe the phenomenon.

You know the space is new when you don’t have the right words to describe the phenomenon.

When there are two opposite sequences of events and you think both are right, you know the space is new.

You know you’re thinking about new things when the harder you try to figure it out the less you know.

You know the space is outside your experience but within your knowledge when you know what to do but you don’t know why.

When you can see the concept in your head but can’t drag it to the whiteboard, you’re swimming in new soup.

When you come back from a walk with a solution to a problem you haven’t yet met, you’re circling new space.

And it’s the same when know what should be but it isn’t – circling new space.

When your old tricks are irrelevant, you’re digging in a new sandbox.

When you come up with a new trick but the audience doesn’t care – new space.

When you know how an experiment will turn out and it turns out you ran an irrational experiment – new space.

When everyone disagrees, the disagreement is a surrogate for the new space.

It’s vital to recognize when you’re swimming in a new space. There is design freedom, new solutions to new problems, growth potential, learning, and excitement. There’s acknowledgment that the old ways won’t cut it. There’s permission to try.

And it’s vital to recognize when you’re squatting in an old space because there’s an acknowledgment that the old ways haven’t cut it. And there’s permission to wander toward a new space.

Image credit — Tambaco The Jaguar

If you want to make a difference, change the design.

Why do factories have 50-ton cranes? Because the parts are heavy and the fully assembled product is heavier. Why is the Boeing assembly facility so large? Because 747s are large. Why does a refrigerator plant have a huge room to accumulate a massive number of refrigerators that fail final test? Because refrigerators are big, because volumes are large, and a high fraction fail final test. Why do factories look as they do? Because the design demands it.

Why do factories have 50-ton cranes? Because the parts are heavy and the fully assembled product is heavier. Why is the Boeing assembly facility so large? Because 747s are large. Why does a refrigerator plant have a huge room to accumulate a massive number of refrigerators that fail final test? Because refrigerators are big, because volumes are large, and a high fraction fail final test. Why do factories look as they do? Because the design demands it.

Why are parts machined? Because the materials, geometries, tolerances, volumes, and cost requirements demand it. Why are parts injection molded? Because the materials, geometries, tolerances, volumes, and cost requirements demand it. Why are parts 3D printed? For prototypes, because the design can tolerate the class of materials that can be printed and can withstand the stresses and temperature of the application for a short time, the geometries are printable, and the parts are needed quickly. For production parts, it’s because the functionality cannot be achieved with a lower-cost process, the geometries cannot be machined or molded, and the customer is willing to pay for the high cost of 3D printing. Why are parts made as they are? Because the design demands it.

Why are parts joined with fasteners? It’s because the engineering drawings define the holes in the parts where the fasteners will reside and the fasteners are called out on the Bills Of Material (BOM). The parts cannot be welded or glued because they’re designed to use fasteners. And the parts cannot be consolidated because they’re designed as separate parts. Why are parts held together with fasteners? Because the design demands it.

If you want to reduce the cost of the factory, change the design so it does not demand the use of 50-ton cranes. If you want to get by with a smaller factory, change the design so it can be built in a smaller factory. If you want to eliminate the need for a large space to store refrigerators that fail final test, change the design so they pass. Yes, these changes are significant. But so are the savings. Yes, a smaller airplane carries fewer people, but it can also better serve a different set of customer needs. And, yes, to radically reduce the weight of a product will require new materials and a new design approach. If you want to reduce the cost of your factory, change the design.

If you want to reduce the cost of the machined parts, change the geometry to reduce cycle time and change to a lower-cost material. Or, change the design to enable near-net forging with some finish machining. If you want to reduce the cost of the injection molded parts, change the geometry to reduce cycle time and change the design to use a lower-cost material. If you want to reduce the cost of the 3D printed parts, change the design to reduce the material content and change the design and use lower-cost material. (But I think it’s better to improve function to support a higher price.) If you want to reduce the cost of your parts, change the design to make possible the use of lower-cost processes and materials.

If you want to reduce the material cost of your product, change the design to eliminate parts with Design for Assembly (DFA). What is the cost of a part that is designed out of the product? Zero. Is it possible to wrongly assemble a part that was designed out? No. Can a part that’s designed out be lost or arrive late? No and no. What’s the inventory cost of a part that’s been designed out? Zero. If you design out the parts is your supply chain more complicated? No, it’s simpler. And for those parts that remain use Design for Manufacturing (DFM) to work with your suppliers to reduce the cost of making the parts and preserve your suppliers’ profit margins.

If you want to sell more, change the design so it works better and solves more problems for your customers. And if you want to make more money, change the design so it costs less to make.

Resurrecting Manufacturing Through Product Simplification

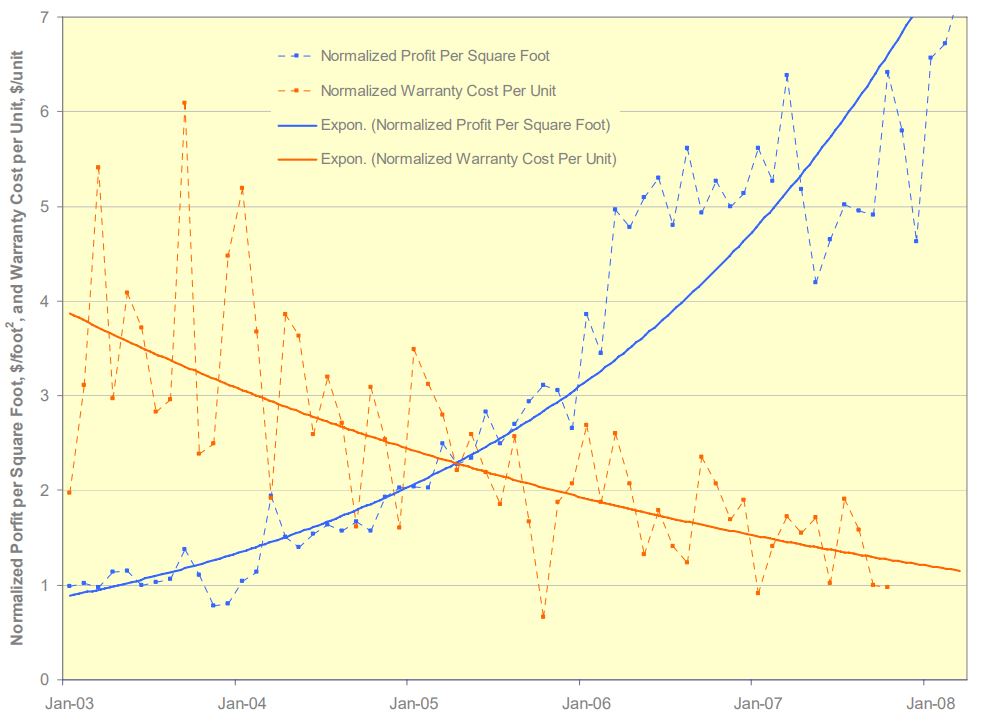

Product simplification can radically improve profits and radically improve product robustness. Here’s a graph of profit per square foot ($/ft^2) which improved by a factor of seven and warranty cost per unit ($/unit), a measure of product robustness), which improved by a factor of four. The improvements are measured against the baseline data of the legacy product which was replaced by the simplified product. Design for Assembly (DFA) was used to simplify the product and Robust Design methods were used to reduce warranty cost per unit.

I will go on record that everyone will notice when profit per square foot increases by a factor of seven.

And I will also go on record that no one will believe you when you predict product simplification will radically improve profit per square foot.

And I will go on record that when warranty cost per unit is radically reduced, customers will notice. Simply put, the product doesn’t break and your customers love it.

But here’s the rub. The graph shows data over five years, which is a long time. And if the product development takes two years, that makes seven long years. And in today’s world, seven years is at least four too many. But take another look at the graph. Profit per square foot doubled in the first two years after launch. Two years isn’t too long to double profit per square foot. I don’t know of a faster way, More strongly, I don’t know of another way to get it done, regardless of the timeline.

I think your company would love to double the profit per square foot of its assembly area. And I’ve shown you the data that proves it’s possible. So, what’s in the way of giving it a try?

For the details about the work, here’s a link – Systematic DFMA Deployment, It Could Resurrect US Manufacturing.

Effectiveness Before Efficiency

Efficient – How do we do more projects with fewer people?

Efficient – How do we do more projects with fewer people?

Effective – Let’s choose the right project.

Would you rather do more projects that miss the mark or fewer that excite the customer?

Efficient – How do we finish the project faster?

Effective – Let’s fully staff the project.

Would you rather burn out the project team or deliver on what the customer wants?

Efficient – How do we reduce product cost by 5%?

Effective – Let’s make customers’ lives easier.

Would you rather reduce the cost or delight the customer?

Efficient – How can we go faster?

Effective – Let’s get it right.

Would you rather go fast and break things or get it right for the customer?

Efficient – How many projects can we run in parallel?

Effective – Let’s fully staff the most important projects.

Would you rather get halfway through four projects or complete two?

Efficient – How do we make progress on as many tasks as possible?

Effective – Let’s work on the critical path.

Would you rather work on things that don’t matter or nail the things that do?

Efficient – How can we complete the most tasks?

Effective – Let’s work on the hardest thing first.

Would you rather learn the whole thing won’t work before or after you waste time on the irrelevant?

If there’s a choice between efficiency and effectiveness, I choose effectiveness.

Image credit — Antarctica Bound

When in doubt, start.

At the start, it’s impossible to know the right thing to do, other than the right thing is to start.

At the start, it’s impossible to know the right thing to do, other than the right thing is to start.

If you think you should have started, but have not, the only thing in the way is you.

If you want to start, get out of your own way, and start.

And even if you’re not in the way, there’s no harm in declaring you ARE in the way and starting.

If you’re afraid, be afraid. And start.

If you’re not afraid, don’t be afraid. And start.

If you can’t choose among the options, all options are equally good. Choose one, and start.

If you’re worried the first thing won’t work, stop worrying, start starting, and find out.

Before starting, you don’t have to know the second thing to do. You only have to choose the first thing to do.

The first thing you do will not be perfect, but that’s the only path to the second thing that’s a little less not perfect.

The second thing is defined by the outcome of the first. Start the first to inform the second.

If you don’t have the bandwidth to start a good project, stop a bad one. Then, start.

If you stop more you can start more.

Starting small is a great way to start. And if you can’t do that, start smaller.

If you don’t start, you can never finish. That’s why starting is so important.

In the end, starting starts with starting. This is The Way.

Image credit — Claudio Marinangeli

What do you do when you’ve done it before?

COPYRIGHT GEOFF HENSON

If you’ve done it before, let someone else do it.

If you’ve done it before, teach someone else to do it.

If you’ve done it before, do it in a tenth of the time.

Do it differently just because you can.

Do it backward. That will make you smile.

Do it with your eyes closed. That will make a statement.

Do its natural extension. That could be fun.

Do the opposite. Then do its opposite. You’ll learn more.

Do what they should have asked for. Life is short.

Do what scares them. It’s sure to create new design space.

Do what obsoletes your most profitable offering. Wouldn’t you rather be the one to do it?

Do what scares you. That’s sure to be the most interesting of all.

Image credit — Geoff Henson

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski