Archive for the ‘Fundementals’ Category

It’s not so easy to move manufacturing work back to the US.

I hear it’s a good idea to move manufacturing work back to the US.

Before getting into what it would take to move manufacturing work back to the US, I think it’s important to understand why manufacturing companies moved their work out of the US. Simply put, companies moved their work out of the US because their accounting systems told them they would make more money if they made their products in countries with lower labor costs. And now that labor costs have increased in these no longer “low-cost countries”, those same accounting systems think there’s more money to be made by bringing manufacturing back to the US.

At a low level of abstraction, manufacturing, as a word, is about making discrete parts like gears, fenders, and tires using machines like gear shapers, stamping machines, and injection molding machines. The cost of manufacturing the parts is defined by the cost of the raw material, the cost of the machines, the cost of energy to power the machines, the cost of the factory, and the cost of the people to run the machines. And then there’s assembly, which, as a word, is about putting those discrete parts together to make a higher-level product. Where manufacturing makes the gears, fenders, and tires, assembly puts them together to make a car. And the cost of assembly is defined by the cost of the factory, the cost of fixtures, and the cost of the people to assemble the parts into the product. And the cost of the finished product is the sum of the cost of making the parts (manufacturing) and the cost of putting them together (assembly).

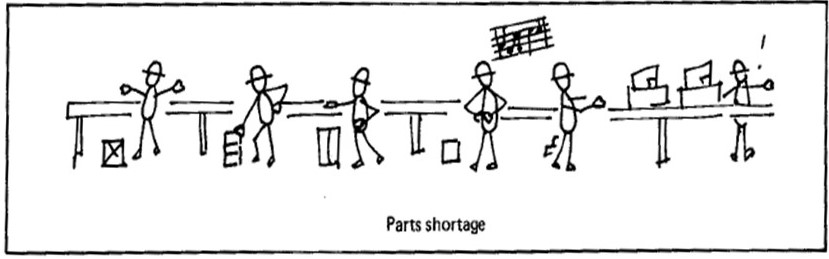

It seems pretty straightforward to make more money by moving the manufacturing of discrete parts back to the US. All that has to happen is to find some empty factory space, buy new machines, land them in the factory, hire the people to run the machines, train them, source the raw material, hire the manufacturing experts to reinvent/automate the manufacturing process to reduce cycle time and reduce labor time and then give them six months to a year to do that deep manufacturing work. That’s quite a list because there’s little factory space available that’s ready to receive machines, the machines cost money, there are few people available to do manufacturing work, the cost to train them is high (and it takes time and there are no trained trainers). But the real hurdles are the deep work required to reinvent/automate the process and the lack of manufacturing experts to do that work. The question you should ask is – Why does the manufacturing process have to be reinvented/automated?

There’s a dirty little secret baked into the accounting systems’ calculations. The cost accounting says there can be no increased profit without reducing the time to make the parts and reducing the labor needed to make them. If the work is moved from country A to country B and the costs (cycle time, labor hours, labor rate) remain constant, the profit remains constant. Simply moving from country A to country B does nothing. Without the deep manufacturing work, profits don’t increase. And if your country doesn’t have the people with the right expertise, that deep manufacturing work cannot happen.

And the picture is similar for moving assembly work back to the US. All that has to happen is to find empty factory space, hire and train people to do the assembly work, reroute the supply chains to the new factory, redesign the product so it can be assembled with an automated assembly line, hire/train the people to redesign the product so it can be assembled in an automated way, design the new automated assembly process, build it, test it, hire/train the automated assembly experts to do that work, hire the people to support and run the automated assembly line, and pay for the multi-million-dollar automated assembly line. And the problems are similar. There’s not a lot of world-class factory space, there are few people available to run the automated assembly line, and the cost of the automated assembly line is significant. But the real problems are the lack of experts to redesign the product for automated assembly and the lack of expertise to design, build, and validate the assembly line. And here are the questions you should ask – Why do we need to automate the assembly process and why does the product have to be redesigned to do that?

It’s that dirty little secret rearing its ugly head again. The cost accounting says there can be no increased profit without reducing the labor to assemble the parts. make them. If the work is moved from country A to country B and the assembly costs (labor hours, labor rate) remain constant, the profit remains constant. Simply moving from country A to country B does nothing. Without deep design work (design for automated assembly) and ultra-deep automated assembly work, profits don’t increase. And if your country doesn’t have the people with the right expertise, that deep design and automated assembly work cannot happen.

If your company doesn’t have the time, money, and capability to reinvent/automate manufacturing processes, it’s a bad idea to move manufacturing work back to the US. It simply won’t work. Instead, find experts who can help you develop/secure the capability to reinvent/automate manufacturing processes to reduce the cost of manufacturing.

If your company doesn’t have the time, money, and capability to design products for automated assembly and to design, build, and validated automated assembly systems, it’s a bad idea to move assembly work back to the US. It, too, simply won’t work. Instead, partner with experts who know how to do that work so you can reduce the cost of assembly.

Short Lessons

Show customers what’s possible. Then listen.

Show customers what’s possible. Then listen.

The best projects are small until they’re not.

Today’s location before tomorrow’s destination.

The best idea requires the least effort.

Ready, fire, aim is better than ready, aim, aim, aim.

Be certain about the uncertainty.

Do so you can discuss.

Put it on one page.

Fail often, but call it learning.

Current state before future state.

Say no now to say yes later.

Effectiveness over efficiency.

Finish one to start one.

Demonstrate before asking.

Sometimes slower is faster.

Build trust before you need it.

“Yin & Yang martini” by AMagill is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Three Important Choices for New Product Development Projects

Choose the right project. When you say yes to a new project, all the focus is on the incremental revenue the project will generate and none of the focus is on unrealized incremental revenue from the projects you said no to. Next time there’s a proposal to start a new project, ask the team to describe the two or three most compelling projects that they are asking the company to say no to. Grounding the go/no-go decision within the context of the most compelling projects will help you avoid the real backbreaker where you consume all your product development resources on something that scratches the wrong itch while you prevent those resources from creating something magical.

Choose the right project. When you say yes to a new project, all the focus is on the incremental revenue the project will generate and none of the focus is on unrealized incremental revenue from the projects you said no to. Next time there’s a proposal to start a new project, ask the team to describe the two or three most compelling projects that they are asking the company to say no to. Grounding the go/no-go decision within the context of the most compelling projects will help you avoid the real backbreaker where you consume all your product development resources on something that scratches the wrong itch while you prevent those resources from creating something magical.

Choose what to improve. Give your customers more of what you gave them last time unless what you gave them last time is good enough. Once goodness is good enough, giving customers more is bad business because your costs increase but their willingness to pay does not. Once your offering meets the customers’ needs in one area, lock it down and improve a different area.

Choose how to staff the projects. There is a strong temptation to run many projects in parallel. It’s almost like our objective is to maximize the number of active projects at the expense of completing them. Here’s the thing about projects – there is no partial credit for partially completed projects. Eight active projects that are eight (or eighty) percent complete generate zero revenue and have zero commercial value. For your most important project, staff it fully. Add resources until adding more resources would slow the project. Then, for your next most important project, repeat the process with your remaining resources. And once a project is completed, add those resources to the pool and start another project. This approach is especially powerful because it prioritizes finishing projects over starting them.

“Three Cows” by Sunfox is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

Speaking your truth is objective evidence you care.

When you see something, do you care enough to say something?

When you see something, do you care enough to say something?

If you disagree, do you care enough to say it out loud?

When the emperor has no clothes, do you care enough to hand them a cover-up?

Cynicism is grounded in caring. Do you care enough to be cynical?

Agreement without truth is not agreement. Do you care enough to disagree?

Violation of the status quo creates conflict. Do you care enough to violate?

If you care, speak your truth.

“Great Grey Owl (Strix nebulosa)” by Bernard Spragg is marked with CC0 1.0.

Radical Cost Reduction and Reinvented Supply Chains

As geopolitical pressures rise, some countries that supply the parts that make up your products may become nonviable. What if there was a way to reinvent the supply chain and move it to more stable regions? And what if there was a way to guard against the use of child labor in the parts that make up your product? And what if there was a way to shorten your supply chain so it could respond faster? And what if there was a way to eliminate environmentally irresponsible materials from your supply chain?

As geopolitical pressures rise, some countries that supply the parts that make up your products may become nonviable. What if there was a way to reinvent the supply chain and move it to more stable regions? And what if there was a way to guard against the use of child labor in the parts that make up your product? And what if there was a way to shorten your supply chain so it could respond faster? And what if there was a way to eliminate environmentally irresponsible materials from your supply chain?

Our supply chains source parts from countries that are less than stable because the cost of the parts made in those countries is low. And child labor can creep into our supply chains because the cost of the parts made with child labor is low. And our supply chains are long because the countries that make parts with the lowest costs are far away. And our supply chains use environmentally irresponsible materials because those materials reduce the cost of the parts.

The thing with the supply chains is that the parts themselves govern the manufacturing processes and materials that can be used, they dictate the factories that can be used and they define the cost. Moving the same old parts to other regions of the world will do little more than increase the price of the parts. If we want to radically reduce cost and reinvent the supply chain, we’ve got to reinvent the parts.

There are methods that can achieve radical cost reduction and reinvent the supply chain, but they are little known. The heart of one such method is a functional model that fully describes all functional elements of the system and how they interact. After the model is complete, there is a straightforward, understandable, agreed-upon definition of how the product functions which the team uses to focus the go-forward design work. And to help them further, the method provides guidelines and suggestions to prioritize the work.

I think radical cost reduction and more robust supply chains are essential to a company’s future. And I am confident in the ability of the methods to deliver solid results. But what I don’t know is: Is the need for radical cost reduction strong enough to cause companies to adopt these methods?

“Zen” by g0upil is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

Three Scenarios for Scaling Up the Work

Breaking up work into small chunks can be a good way to get things started. Because the scope of each chunk is small, the cost of each chunk is small making it easier to get approval to do the work. The chunk approach also reduces anxiety around the work because if nothing comes from the chunk, it’s not a big deal because the cost of the work is so low. It’s a good way to get started, and it’s a good way to do a series of small chunks that build on each other. But what happens when the chunks are successful and it’s time to scale up the investment by a factor of several hundred thousand or a million?

Breaking up work into small chunks can be a good way to get things started. Because the scope of each chunk is small, the cost of each chunk is small making it easier to get approval to do the work. The chunk approach also reduces anxiety around the work because if nothing comes from the chunk, it’s not a big deal because the cost of the work is so low. It’s a good way to get started, and it’s a good way to do a series of small chunks that build on each other. But what happens when the chunks are successful and it’s time to scale up the investment by a factor of several hundred thousand or a million?

The scaling scenario. When the early work (the chunks) was defined an agreement in principle was created that said the larger investment would be made in a timely way if the small chunks demonstrated the viability of a whole new offering for your customers. The result of this scenario is a large investment is allocated quickly, resources flow quickly, and the scaling work begins soon after the last chunk is finished. This is the least likely scenario.

The more chunks scenario. When the chunks were defined, everyone was excited that the novel work had actually started and there was no real thought about the resources required to scale it into something meaningful and material. Since the resources needed to scale were not budgeted, the only option to keep things going is to break up the work into another series of small chunks. Though the organization sees this as progress, it’s not. The only thing that can deliver the payout the organization needs is to scale up the work. The follow-on chunks distract the company and let it think there is progress, when, really, there is only delayed scaling.

The scale next year scenario. When the chunks were defined, no one thought about scaling so there was no money in the budget to scale. A plan and cost estimate are created for the scaling work and the package waits to be assessed as part of the annual planning process. And as the waiting happens, the people that did the early work (the chunks) move on to other projects and are not available to do the scaling work even if the work gets funded next year. And because the work is new it requires new infrastructure, new resources, new teams, new thinking, and maybe a new company. All this newness makes the price tag significant and it may require more than one annual planning cycle to justify the expense and start the work.

Scaling a new invention into a full-sized business is difficult and expensive, but if you’re looking to create radical growth, scaling is the easiest and least expensive way to go.

“100 Dollar Bills” by Philip Taylor PT is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

How To Complete More Projects

Before you decide which project to start, decide which project you’ll stop.

Before you decide which project to start, decide which project you’ll stop.

The best way to stop a project is to finish it. The next best way is to move the resources to a more important project.

If you find yourself starting before finishing, stop starting and start finishing.

People’s output is finite. Adding a project that violates their human capacity will not result in more completed projects but will cause your best people to leave.

If people’s calendars are full, the only way to start something new is to stop something old.

If you start more projects than you finish, you’re stopping projects before they’re finished. You’re probably not stopping them in an official way, rather, you’re letting them wither and die a slow death. But you’re definitely stopping them.

When you start more projects than you finish, the number of active projects increases. And without a corresponding increase in resources, fewer projects are completed.

The best way to reduce the number of projects you finish is to start new projects.

Make a list of the projects that you stopped over the last year. Is it a short list?

Make a list of projects that are understaffed and under-resourced yet still running in the background. Is that list longer?

A rule to live by: If a project is understaffed, staff it or stop it.

If you can’t do that, reduce the scope to fit the resources or stop it.

Would you prefer to complete one project at a time or do three simultaneously and complete none?

When it comes to stopping projects, it’s stopped or it isn’t. There’s no partial credit for talking about stopping a project.

If you want to learn if a project is worthy of more resources, stop the project. If the needed resources flow to the project, the project is worthy. If not, at least you stopped a project that shouldn’t have been started.

People don’t like working on projects where the work content is greater than the resources to do the work. These projects are a major source of burnout.

If you know you have too many projects, everyone else knows it too. Stop the weakest projects or your credibility will suffer.

“Circus Renz Berlin, Holland 2011” by dirkjanranzijn is licensed under CC BY-ND 2.0.

It’s good to have experience, until the fundamentals change.

We use our previous experiences as context for decisions we make in the present. When we have a bad experience, the experience-context pair gets stored away in our memory so that we can avoid a similar bad outcome when a similar context arises. And when we have a good experience, or we’re successful, that memory-context pair gets stored away for future reuse. This reuse approach saves time and energy and, most of the time keeps us safe. It’s nature’s way of helping us do more of what works and less of what doesn’t.

We use our previous experiences as context for decisions we make in the present. When we have a bad experience, the experience-context pair gets stored away in our memory so that we can avoid a similar bad outcome when a similar context arises. And when we have a good experience, or we’re successful, that memory-context pair gets stored away for future reuse. This reuse approach saves time and energy and, most of the time keeps us safe. It’s nature’s way of helping us do more of what works and less of what doesn’t.

The system works well when we correctly match the historical context with today’s context and the system’s fundamentals remain unchanged. There are two potential failure modes here. The first is when we mistakenly map the context of today’s situation with a memory-context pair that does not apply. With this, we misapply our experience-based knowledge in a context that demands different knowledge and different decisions. The second (and more dangerous) failure mode is when we correctly identify the match between past and current contexts but the rules that underpin the context have changed. Here, we feel good that we know how things will turn out, and, at the same time, we’re oblivious to the reality that our experience-based knowledge is out of date.

“If a cat sits on a hot stove, that cat won’t sit on a hot stove again. That cat won’t sit on a cold stove either. That cat just don’t like stoves.” Mark Twain

If you tried something ten years ago and it failed, it’s possible that the underpinning technology has changed and it’s time to give it another try.

If you’ve been successful doing the same thing over the last ten years, it’s possible that the underpinning business model has changed and it’s time to give a different one a try.

“Hissing cat” by Consumerist Dot Com is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Students, Teachers, and Learning

If the student has no interest, they are not yet a student and it’s not yet time for learning.

If the student has no interest, they are not yet a student and it’s not yet time for learning.

Learning comes hard, especially when it’s not wanted.

The teacher that tries to teach a student that’s not yet a student is not yet a teacher.

There can be no teacher without a student.

If there’s no doing, there’s no learning. And it’s the same if there’s no theory.

Apprenticeship creates deep learning, but it takes two years.

Learning is inefficient, but it’s far more efficient than not learning.

When you know the student is ready, turn your back so they can see it for themselves.

Objective evidence of deep learning: When students can navigate situations that are outside the curriculum.

“May 14, 2006: Happy Mother’s Day” by Matt McGee is licensed under CC BY-ND 2.0.

The first step is to admit you have a problem.

Nothing happens until the pain caused by a problem is greater than the pain of keeping things as they are.

Nothing happens until the pain caused by a problem is greater than the pain of keeping things as they are.

Problems aren’t bad for business. What’s bad for business is failing to acknowledge them.

The consternation that comes from the newly-acknowledged problem is the seed from which the solution grows.

There can be no solution until there’s a problem.

When the company doesn’t have a big problem, it has a bigger problem – complacency.

If you want to feel anxious about something, feel anxious that everything is going swimmingly.

Successful companies tolerate problems because they can.

Successful companies that tolerate their problems for too long become unsuccessful companies.

What happens to people in your company that talk about big problems? Are they celebrated, ignored, or ostracized? And what behavior does that reinforce? And how do you feel about that?

When everyone knows there’s a problem yet it goes unacknowledged, trust erodes.

And without trust, you don’t have much.

Helping helps.

If you think asking for help is a sign of weakness, you won’t get the help you deserve.

If you think asking for help is a sign of weakness, you won’t get the help you deserve.

If the people around you think asking for help is a sign of weakness, find new people.

As a leader, asking others for help makes it easier for others to ask for help.

When someone asks you for help, help them.

If you’re down in the dumps, help someone.

Helping others is like helping yourself twice.

Helping is caring in action.

If you help someone because you want something in return, people recognize that for what it is.

Done right, helping makes both parties stand two inches taller.

Sometimes the right help gives people the time and space to work things out for themselves.

Sometimes the right help asks people to do work outside their comfort zone.

Sometimes the right help is a difficult conversation.

Sometimes the right help is a smile, a phone call, or a text.

And sometimes the right help isn’t recognized as help until six months after the fact.

Here’s a rule to live by – When in doubt, offer help.

“Helping Daddy” by audi_insperation is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski