Archive for the ‘Floor Space’ Category

Resurrecting Manufacturing Through Product Simplification

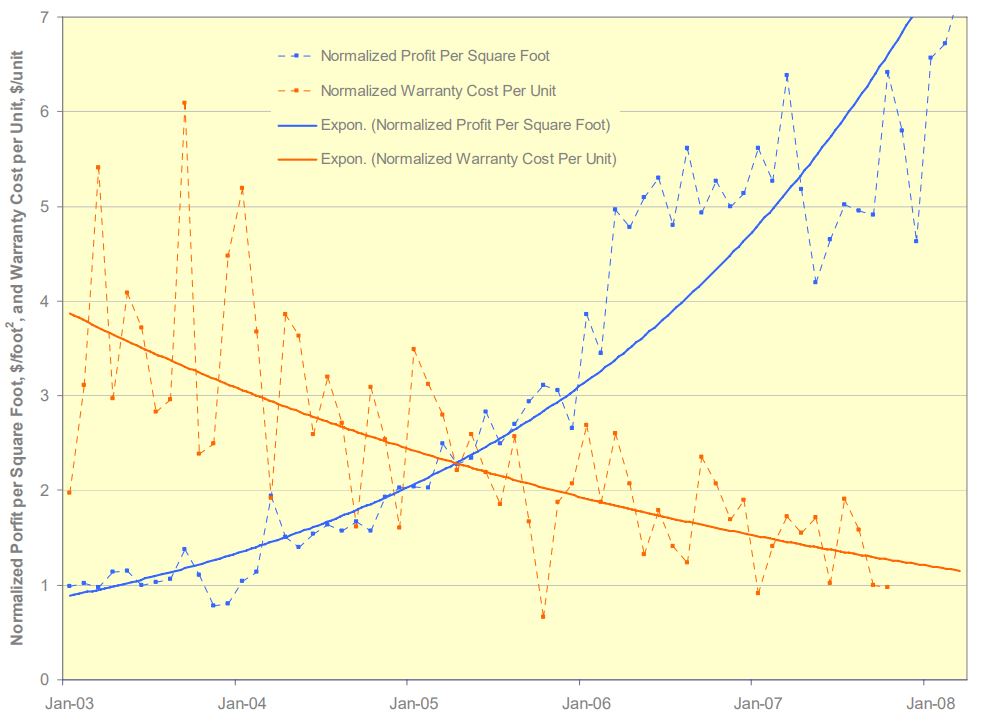

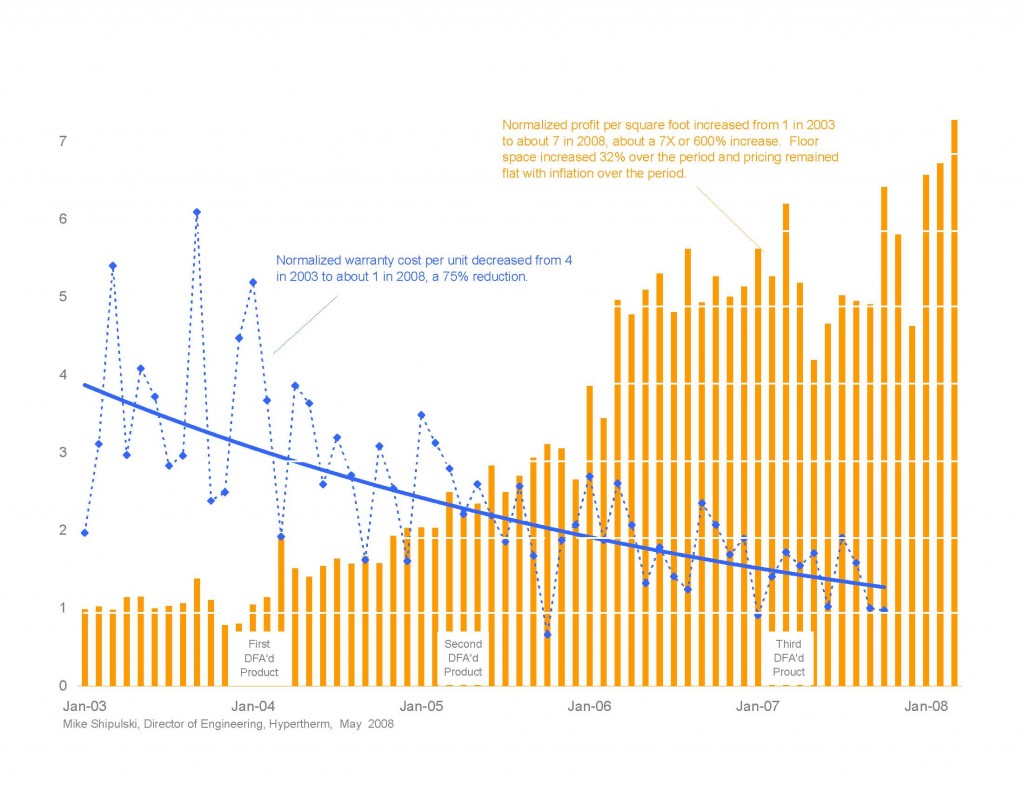

Product simplification can radically improve profits and radically improve product robustness. Here’s a graph of profit per square foot ($/ft^2) which improved by a factor of seven and warranty cost per unit ($/unit), a measure of product robustness), which improved by a factor of four. The improvements are measured against the baseline data of the legacy product which was replaced by the simplified product. Design for Assembly (DFA) was used to simplify the product and Robust Design methods were used to reduce warranty cost per unit.

I will go on record that everyone will notice when profit per square foot increases by a factor of seven.

And I will also go on record that no one will believe you when you predict product simplification will radically improve profit per square foot.

And I will go on record that when warranty cost per unit is radically reduced, customers will notice. Simply put, the product doesn’t break and your customers love it.

But here’s the rub. The graph shows data over five years, which is a long time. And if the product development takes two years, that makes seven long years. And in today’s world, seven years is at least four too many. But take another look at the graph. Profit per square foot doubled in the first two years after launch. Two years isn’t too long to double profit per square foot. I don’t know of a faster way, More strongly, I don’t know of another way to get it done, regardless of the timeline.

I think your company would love to double the profit per square foot of its assembly area. And I’ve shown you the data that proves it’s possible. So, what’s in the way of giving it a try?

For the details about the work, here’s a link – Systematic DFMA Deployment, It Could Resurrect US Manufacturing.

It’s not so easy to move manufacturing work back to the US.

I hear it’s a good idea to move manufacturing work back to the US.

Before getting into what it would take to move manufacturing work back to the US, I think it’s important to understand why manufacturing companies moved their work out of the US. Simply put, companies moved their work out of the US because their accounting systems told them they would make more money if they made their products in countries with lower labor costs. And now that labor costs have increased in these no longer “low-cost countries”, those same accounting systems think there’s more money to be made by bringing manufacturing back to the US.

At a low level of abstraction, manufacturing, as a word, is about making discrete parts like gears, fenders, and tires using machines like gear shapers, stamping machines, and injection molding machines. The cost of manufacturing the parts is defined by the cost of the raw material, the cost of the machines, the cost of energy to power the machines, the cost of the factory, and the cost of the people to run the machines. And then there’s assembly, which, as a word, is about putting those discrete parts together to make a higher-level product. Where manufacturing makes the gears, fenders, and tires, assembly puts them together to make a car. And the cost of assembly is defined by the cost of the factory, the cost of fixtures, and the cost of the people to assemble the parts into the product. And the cost of the finished product is the sum of the cost of making the parts (manufacturing) and the cost of putting them together (assembly).

It seems pretty straightforward to make more money by moving the manufacturing of discrete parts back to the US. All that has to happen is to find some empty factory space, buy new machines, land them in the factory, hire the people to run the machines, train them, source the raw material, hire the manufacturing experts to reinvent/automate the manufacturing process to reduce cycle time and reduce labor time and then give them six months to a year to do that deep manufacturing work. That’s quite a list because there’s little factory space available that’s ready to receive machines, the machines cost money, there are few people available to do manufacturing work, the cost to train them is high (and it takes time and there are no trained trainers). But the real hurdles are the deep work required to reinvent/automate the process and the lack of manufacturing experts to do that work. The question you should ask is – Why does the manufacturing process have to be reinvented/automated?

There’s a dirty little secret baked into the accounting systems’ calculations. The cost accounting says there can be no increased profit without reducing the time to make the parts and reducing the labor needed to make them. If the work is moved from country A to country B and the costs (cycle time, labor hours, labor rate) remain constant, the profit remains constant. Simply moving from country A to country B does nothing. Without the deep manufacturing work, profits don’t increase. And if your country doesn’t have the people with the right expertise, that deep manufacturing work cannot happen.

And the picture is similar for moving assembly work back to the US. All that has to happen is to find empty factory space, hire and train people to do the assembly work, reroute the supply chains to the new factory, redesign the product so it can be assembled with an automated assembly line, hire/train the people to redesign the product so it can be assembled in an automated way, design the new automated assembly process, build it, test it, hire/train the automated assembly experts to do that work, hire the people to support and run the automated assembly line, and pay for the multi-million-dollar automated assembly line. And the problems are similar. There’s not a lot of world-class factory space, there are few people available to run the automated assembly line, and the cost of the automated assembly line is significant. But the real problems are the lack of experts to redesign the product for automated assembly and the lack of expertise to design, build, and validate the assembly line. And here are the questions you should ask – Why do we need to automate the assembly process and why does the product have to be redesigned to do that?

It’s that dirty little secret rearing its ugly head again. The cost accounting says there can be no increased profit without reducing the labor to assemble the parts. make them. If the work is moved from country A to country B and the assembly costs (labor hours, labor rate) remain constant, the profit remains constant. Simply moving from country A to country B does nothing. Without deep design work (design for automated assembly) and ultra-deep automated assembly work, profits don’t increase. And if your country doesn’t have the people with the right expertise, that deep design and automated assembly work cannot happen.

If your company doesn’t have the time, money, and capability to reinvent/automate manufacturing processes, it’s a bad idea to move manufacturing work back to the US. It simply won’t work. Instead, find experts who can help you develop/secure the capability to reinvent/automate manufacturing processes to reduce the cost of manufacturing.

If your company doesn’t have the time, money, and capability to design products for automated assembly and to design, build, and validated automated assembly systems, it’s a bad idea to move assembly work back to the US. It, too, simply won’t work. Instead, partner with experts who know how to do that work so you can reduce the cost of assembly.

The best time to design cost out of our products is now.

With inflation on the rise and sales on the decline, the time to reduce costs is now.

With inflation on the rise and sales on the decline, the time to reduce costs is now.

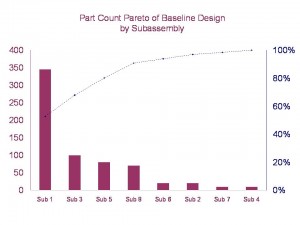

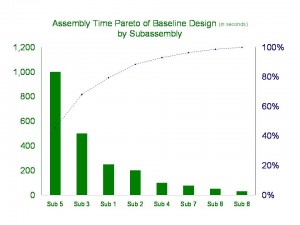

But before you can design out the cost you’ve got to know where it is. And the best way to do that is to create a Pareto chart that defines product cost for each subassembly, with the highest cost subassemblies on the left and the lowest cost on the right. Here’s a pro tip – Ignore the subassemblies on the right.

Use your costed Bill of Materials (BOMs) to create the Paretos. You’ll be told that the BOMs are wrong (and they are), but they are right enough to learn where the cost is.

For each of the highest-cost subassemblies, create a lower-level Pareto chat that sorts the cost of each piece-part from highest to lowest. The pro tip applies here, too – Ignore the parts on the right.

Because the design community designed in the cost, they are the ones who must design it out. And to help them prioritize the work, they should be the ones who create the Pareto charts from the BOMs. They won’t like this idea, but tell them they are the only ones who can secure the company’s future profits and buy them lots of pizza.

And when someone demands you reduce labor costs, don’t fall for it. Labor cost is about 5% of the product cost, so reducing it by half doesn’t get you much. Instead, make a Pareto chart of part count by subassembly. Focus the design effort on reducing the part count of subassemblies on the left. Pro tip – Ignore the subassemblies on the right. The labor time to assemble parts that you design out is zero, so when demand returns, you’ll be able to pump out more products without growing the footprint of the factory. But, more importantly, the cost of the parts you design out is also zero. Designing out the parts is the best way to reduce product costs.

Pro tip – Set a cost reduction goal of 35%. And when they complain, increase it to 40%.

In parallel to the design work to reduce part count and costs, design the test fixtures and test protocols you’ll use to make sure the new, lower-cost design outperforms the existing design. Certainly, with fewer parts, the new one will be more reliable. Pro tip – As soon as you can, test the existing design using the new protocols because the only way to know if the new one is better is to measure it against the test results of the old one.

And here’s the last pro tip – Start now.

Image credit — aisletwentytwo

Product Thinking

Product costs, without product thinking, drop 2% per year. With product thinking, product costs fall by 50%, and while your competitors’ profit margins drift downward, yours are too high to track by conventional methods. And your company is known for unending increases in stock price and long term investment in all the things that secure the future.

The supply chain, without product thinking, improves 3% per year. With product thinking, longest lead processes are eliminated, poorest yield processes are a thing of the past, problem suppliers are gone, and your distributers associate your brand with uninterrupted supply and on time delivery.

Product robustness, without product thinking, is the same year-on-year. Re-injecting long forgotten product thinking to simplify the product, product robustness jumps to unattainable levels and warranty costs plummet. And your brand is known for products that simply don’t break.

Rolled throughput yield is stalled at 90%. With product thinking, the product is simplified, opportunities for defects are reduced, and throughput skyrockets due to improved RTY. And your brand is known as a good value – providing good, repeatable functionality at a good price.

Lean, without product thinking has delivered wonderful results, but the low hanging fruit is gone and lean is moving into the back office. With product thinking, the design is changed and value-added work is eliminated along with its associated non-value added work (which is about 8 times bigger); manufacturing monuments with their long changeover times are ripped out and sold to your competitors; work from two factories is consolidated into one; new work is taken on to fill the emptied factories; and profit per square foot triples. And your brand is known for best-in-class quality, unbeatable on time delivery, world class performance, and pioneering the next generation of lean.

The sales argument is low price and good payment terms. With product thinking, the argument starts with product performance and ends with product reliability. The sales team is energized, and your brand is linked with solid products that just plain work.

The marketing approach is stickers and new packaging. With product thinking, it’s based on competitive advantage explained in terms of head-to-head performance data and a richer feature set. And your brand stands for winning technology and killer products.

Product thinking isn’t for everyone. But for those that try – your brand will thank you.

Missing Element of Lean – Assembly Magazine article

With its strong focus on waste reduction of processes, lean has been a savior for those who’ve made it out of the great recession. But what’s next? I argue the next level of savings will come from adding a product focus to lean’s well-developed process focus. For the complete Assembly Magazine article (one page), click here.

With its strong focus on waste reduction of processes, lean has been a savior for those who’ve made it out of the great recession. But what’s next? I argue the next level of savings will come from adding a product focus to lean’s well-developed process focus. For the complete Assembly Magazine article (one page), click here.

Too afraid to make money and create jobs.

What if you could double your factory throughput without adding people?

What if you could double your factory throughput without adding people?

What if you could reduce your product costs by 50%?

How much money would you make?

How many jobs would you create?

Why aren’t you doing it?

What are you afraid of?

Custom Model, exploring customized manufacturing (Mechanical Engineering Magazine)

By reducing parts count and easing assembly, one plasma cutter maker explores customized manufacturing.

By reducing parts count and easing assembly, one plasma cutter maker explores customized manufacturing.

By Jean Thilmany, Associate Editor, Mechanical Engineering Magazine

Ask nearly any engineer or manufacturer about customized manufacturing and—to a person—they’ll all say the same thing: Have you heard the Dell story?

Dell is offered up again and again as the number one example of customized manufacturing done right and done successfully. Shortly after its founding in 1984, Dell began what it calls a configure-to-order approach to manufacturing. The computer company lets customers customize their own computers on the Dell Web site. Buyers select how much memory and disk space they desire and the resulting computer is manufactured and shipped to them.

The approach has helped the computer maker see skyrocket growth. Last year, it held the second-highest spot for desktops and laptops shipped, behind Hewlett Packard, according to market-share numbers from research firm International Data Corp. in Framingham, Mass.

Manufacturers—particularly electronics manufacturers—have long been taking notice. Many of them are investigating how the configure-to-order model could be put to use at their own companies. And some of them have implemented the method—along with the necessary software to get the job done—with great success.

Take Hypertherm Inc. of Hanover, N.H., maker of plasma metal cutting equipment. The company has recently started allowing customers to choose online from ten CNC Edge Pro product configurations, up from three configurations in the former product line, said John Sobr, head designer on the project.

Hypertherm recently redesigned its plasma metal cutting equipment to reduce part count by 27 percent while doubling the number of inputs available. Customers can now choose from ten product configurations.

Pareto’s Three Lenses for Product Design

Axiom 1 – Time is short, so make sure you’re working on the most important stuff.

Axiom 1 – Time is short, so make sure you’re working on the most important stuff.

Axiom 2 – You can’t design out what you can’t see.

In product development, these two axioms can keep you out of trouble. They’re two sides of the same coin, but I’ll describe them one at a time and hope it comes together in the end.

With Axiom 1, how do you make sure you’re working on the most important stuff? We all know it’s function first – no learning there. But, sorry design engineers, it doesn’t end with function. You must also design for lean, for cost, and factory floor space. Great. More things to design for. Didn’t you say time was short? How the hell am I going to design for all that?

Now onto the seeing business of Axiom 2. If we agree that lean, cost, and factory floor space are the right stuff, we must “see it” if we are to design it out. See lean? See cost? See factory floor space? You’re nuts. How do you expect us to do that?

Pareto to the rescue – use Pareto charts to identify the most important stuff, to prioritize the work. With Pareto, it’s simple: work on the biggest bars at the expense of the smaller ones. But, Paretos of what?

There is no such thing as a clean sheet design – all new product designs have a lineage. A new design is based on an existing design, a baseline design, with improvements made in several areas to realize more features or better function defined by the product specification. The Pareto charts are created from the baseline design to allow you to see the things to design out (Axiom 2). But what lenses to use to see lean, cost, and factory floor space?

Here are Pareto’s three lenses so see what must be seen:

To lean out lean out your factory, design out the parts. Parts create waste and part count is the surrogate for lean.

To design out cost, measure cost. Cost is the surrogate for cost.

To design out factory floor space, measure assembly time. Since factory floor space scales with assembly time, assembly time is the surrogate for factory floor space.

Now that your design engineers have created the right Pareto charts and can see with the right glasses, they’re ready to focus their efforts on the most important stuff. No boiling the ocean here. For lean, focus on part count of subassembly 1; for cost, focus on the cost of subassemblies 2 and 4; for floor space, focus on assembly time of subassembly 5. Leave the others alone.

Focus is important and difficult, but Pareto can help you see the light.

Fasteners Can Consume 20-50% of Assembly Labor

The data-driven people in our lives tell us that you can’t improve what you can’t measure. I believe that. And it’s no different with product cost. Before improving product cost, before designing it out, you have to know where it is. However, it can be difficult to know what really creates cost. Not all parts and features are created equal; some create more cost than others, and it’s often unclear which are the heavy hitters. Sometimes the heavy hitters don’t look heavy, and often are buried deeply within the hidden factory.

The data-driven people in our lives tell us that you can’t improve what you can’t measure. I believe that. And it’s no different with product cost. Before improving product cost, before designing it out, you have to know where it is. However, it can be difficult to know what really creates cost. Not all parts and features are created equal; some create more cost than others, and it’s often unclear which are the heavy hitters. Sometimes the heavy hitters don’t look heavy, and often are buried deeply within the hidden factory.

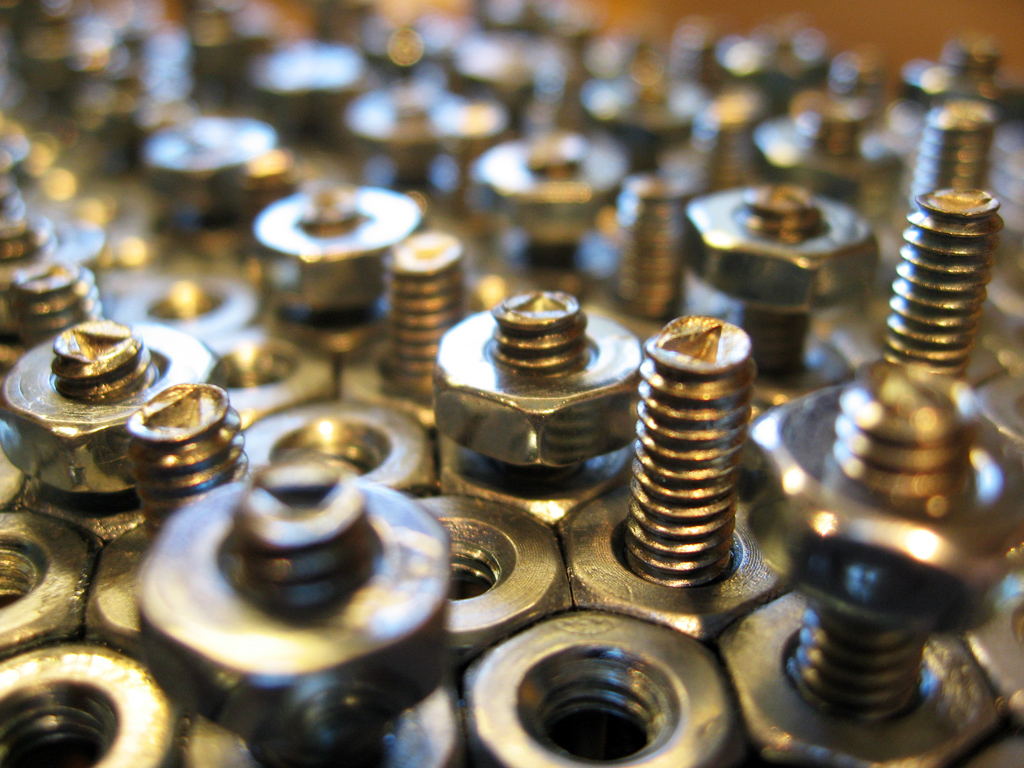

Measure, measure, measure. That’s what the black belts say. However, it’s difficult to do well with product cost since our costing methods are hosed up and our measurement systems are limited. What do I mean? Consider fasteners (e.g., nuts, bolts, screws, and washers), the product’s most basic life form. Because fasteners are not on the BOM, they’re not part of product cost. Here’s the party line: it’s overhead to be shared evenly across all the products in a socialist way. That’s not a big deal, right? Wrong. Although fasteners don’t cost much in ones and twos, they do add up. 300-500 pieces per unit times the number of units per year makes for a lot of unallocated and untracked cost. However, a more significant issue with those little buggers is they take a lot of time attach to the product. For example, using standard time data from DFMA software, assembly of a 1/4″ nut with a bolt, locktite, a lockwasher, and cleanup takes 50 seconds. That’s a lot of time. You should be asking yourself what that translates to in your product. To figure it out, multiply the number nut/bolt/washer groupings by 50 seconds and multiply the result by the number of units per year. Actually, never mind. You can’t do the calculation because you don’t know the number of nut/bolt/washer combinations that are in your product. You could try to query your BOMs, but the information is likely not there. Remember, fasteners are overhead and not allocated to product. Have you ever tried to do a cost reduction project on overhead? It’s impossible. Because overhead inflicts pain evenly to all, no one is responsible to reduce it.

With fasteners, it’s like death by a thousand cuts.

The time to attach them can be as much as 20-50% of labor. That’s right, up to 50%. That’s like paying 20-50% of your folks to attach fasteners all day. That should make you sick. But it’s actually worse than that. From Line Design 101, the number of assembly stations is proportional to demand times labor time. Since fasteners inflate labor time, they also inflate the number of assembly stations, which, in turn, inflates the factory floor space needed to meet demand. Would you rather design out fasteners or add 15% to your floor space? I know you can get good deals on factory floor space due to the recession, but I’d still rather design out fasteners.

Even with the amount of assembly labor consumed by fasteners, our thinking and computer systems are blind to them and the associated follow-on costs. And because of our vision problems, the design community cannot be held accountable to design out those costs. We’ve given them the opportunity to play dumb and say things like, “Those fastener things are free. I’m not going to spend time worrying about that. It’s not part of the product cost.” Clearly not an enlightened statement, but it’s difficult to overcome without cost allocation data for the fasteners.

The work-around for our ailing thinking and computer-based cost tracking systems is simple: get the design engineers out to the production floor to build the product. Have them experience first hand how much waste is in the product. They’ll come back with a deep-in-the-gut understanding of how things really are. Then, have them use DFMA software to score the existing design, part-by-part, feature-by-feature. I guarantee everyone will know where the cost is after that. And once they know where the cost is, it will be easy for them to design it out.

I have data to support my assertion that fasteners can make up 20-50% of labor time, but don’t take my word for it. Go out to the factory floor, shut your eyes and listen. You’ll likely hear the never ending song of the nut runners. With each chirp, another nut is fastened to its bolt and washer, and another small bit of labor and factory floor space is consumed by the lowly fastener.

Boothroyd Dewhurst DFMA Helps Slash Warranty Costs and Boost Factory Floor Profits 600 Percent at Hypertherm

Five-year implementation of DFMA software by Hypertherm creates higher profits and strong business model for improving U.S. global competitiveness

WAKEFIELD, R.I., and HANOVER, N.H.,USA, June 2, 2008—Hypertherm, the world leader in plasma metal cutting technology, has achieved a 600 percent increase in profit per square foot of factory floor space using Boothroyd Dewhurst, Inc., Design for Manufacture and Assembly (DFMA®) software within a five-year redesign program. Correspondingly, warranty cost per unit has declined more than 75 percent during that same period, from January 2003 to January 2008.

Free Up Floor Space with Design for Assembly and Part Count Reduction

Free Up Floor Space with Design for Assembly and Part Count Reduction

By Mike Shipulski, Director of Engineering, Hypertherm, Inc

Design for Assembly (DFA) methods have been around for over 25 years, but the number of companies using the methods is surprisingly low given that they are straight-forward, fast, and produce significant savings in traditional Value Added (VA) metrics: labor content and material cost. Now that LEAN has raised the world’s awareness of the importance of reducing Non-Value Added (NVA) activities, the true value of DFA methods can be appreciated.

As a first principle, Design for Assembly (DFA) methods focus on part count reduction. Part count reduction results in labor content reduction (fewer parts to assemble) and material cost reduction Read the rest of this entry »

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski