Archive for the ‘Feelings’ Category

28 Things I Learned the Hard Way

- If you want to have an IoT (Internet of Things) program, you’ve got to connect your products.

- If you want to build trust, give without getting.

- If you need someone with experience in manufacturing automation, hire a pro.

- If the engineering team wants to spend a year playing with a new technology, before the bell rings for recess ask them what solution they’ll provide and then go ask customers how much they’ll pay and how many they’ll buy.

- If you don’t have the resources, you don’t have a project.

- If you know how it will turn out, let someone else do it.

- If you want to make a friend, help them.

- If your products are not connected, you may think you have an IoT program, but you have something else.

- If you don’t have trust, you have just what you earned.

- If you hire a pro in manufacturing automation, listen to them.

- If Marketing has an optimistic sales forecast for the yet-to-be-launched product, go ask customers how much they’ll pay and how many they’ll buy.

- If you don’t have a project manager, you don’t have a project.

- If you know how it will turn out, teach someone else how to do it.

- If a friend needs help, help them.

- If you want to connect your products at a rate faster than you sell them, connect the products you’ve already sold.

- If you haven’t started building trust, you started too late.

- If you want to pull in the delivery date for your new manufacturing automation, instead, tell your customers you’ve pushed out the launch date.

- If the VP knows it’s a great idea, go ask customers how much they’ll pay and how many they’ll buy.

- If you can’t commercialize, you don’t have a project.

- If you know how it will turn out, do something else.

- If a friend asks you twice for help, drop what you’re doing and help them immediately.

- If you can’t figure out how to make money with IoT, it’s because you’re focusing on how to make money at the expense of delivering value to customers.

- If you don’t have trust, you don’t have much

- If you don’t like extreme lead times and exorbitant capital costs, manufacturing automation is not for you.

- If the management team doesn’t like the idea, go ask customers how much they’ll pay and how many they’ll buy.

- If you’re not willing to finish a project, you shouldn’t be willing to start.

- If you know how it will turn out, it’s not innovation.

- If you see a friend that needs help, help them ask you for help.

Image credit — openDemocracy

Without trust, there is nothing.

If someone treats you badly, that’s on them. You did nothing wrong.

If someone treats you badly, that’s on them. You did nothing wrong.

When you do your best and your boss tells you otherwise, your boss is unskillful.

If you make a mistake, own it. And if someone gives you crap about it, disown them.

If someone is untruthful, hold them accountable. If they’re still untruthful, double down and hold them accountable times two.

If you’re treated unfairly, it’s because someone has low self-esteem. And if you get mad at them, it’s because you have low self-esteem.

What people think about you is none of your concern, especially if they treat you badly.

If you see something, say something, especially when you see a leader treat their team badly.

A leader that treats you badly isn’t a leader.

If you don’t trust your leader, find a new leader. And if you can’t find a new leader to trust, find a new company.

If someone belittles you, that’s about them. Try to forgive them. And if you can’t, try again.

No one deserves to be treated badly, even if they treat you badly.

If you have high expectations for your leader and they fall short, that says nothing about your expectations.

If someone’s behavior makes you angry, that’s about you. And when your behavior makes someone angry, the calculus is the same.

When actions are different from the words, believe the actions.

When the words are different than the actions, there can be no trust.

The best work is built on trust. And without trust, the work will not be the best.

If you don’t feel comfortable calling people on their behavior it’s because you don’t believe they’ll respond in good faith.

If you don’t think someone is truthful, nothing good will come from working with them.

If you can’t be truthful it’s because there is insufficient trust.

Without trust there is nothing.

If there’s a mismatch between someone’s words and their actions, call them on their actions.

If you call someone on their actions and they use their words to try to justify their actions, run away.

As a leader, be truthful and forthcoming.

Have you ever felt like you weren’t getting the truth from your leader? You know – when they say something and you know that’s not what they really think. Or, when they share their truth but you can sense that they’re sharing only part of the truth and withholding the real nugget of the truth? We really have no control over the level of forthcoming of our leaders, but we do have control over how we respond to their incomplete disclosure.

There are times when leaders cannot, by law, disclose things. But, even then, they can make things clear without disclosing what legally cannot be disclosed. For example, they can say: “That’s a good question and it gets to the heart of the situation. But, by law, I cannot answer that question.” They did not answer the question, but they did. They let you know that you understand the situation; they let you know that there is an answer; and the let you know why they cannot share it with you. As the recipient of that non-answer answer, I respect that leader.

There are also times when a leader withholds information or gives a strategically partial response for inappropriate reasons. When a leader withholds information to manipulate or control, that’s inappropriate. It’s also bad leadership. When a leader withholds information from their smartest team members, they lose trust. And when leaders lose trust, the best people are crestfallen and withhold their best work. The thinking goes like this. If my leader doesn’t trust me enough to share the complete set of information with me it’s because they don’t think I’m worthy of their trust and they don’t think highly of me. And if they don’t think I’m worthy of their trust, they don’t understand who I am and what I stand for. And if they don’t understand me and know what I stand for, they’re not worthy of my best work.

As a leader, you must share all you can. And when you can’t, you must tell your team there are things you can’t share and tell them the reasons why. Your team can handle the fact that there are some things you cannot share. But what your team cannot hand is when you withhold information so you can gain the upper hand on them. And your team can tell when you’re withholding with your best interest in mind. Remember, you hired them because they were smart, and their smartness doesn’t go away just because you want to control them.

If your direct reports always tell you they can get it done even when they don’t have the capacity and capability, that’s not the behavior you want. If your direct reports tell you they can’t get it done when they can’t get it done, that’s the behavior you want. But, as a leader, which behavior do you reward? Do you thank the truthful leader for being truthful about the reality of insufficient resources and do you chastise the other leader for telling you what you want to hear? Or, do you tell the truthful leader they’re not a team player because team players get it done and praise the unjustified can-do attitude of the “yes man” leader? As a leader, I suggest you think deeply about this. As a direct report of a leader, I can tell you I’ve been punished for responding in way that was in line with the reality of the resources available to do the work. And I can also tell you that I lost all respect for that leader.

As a leader, you have three types of direct reports. Type I are folks are happy where they are and will do as little as possible to keep it that way. Type II are people that are striving for the next promotion and will tell you whatever you want to hear in order to get the next job. Type III are the non-striving people who will tell you what you need to hear despite the implications to their career. Type I people are good to have on your team. They know what they can do and will tell you when the work is beyond their capability. Type II people are dangerous because they think only of themselves. They will hang you out to dry if they think it will advance their career. And Type III people are priceless.

Type III people care enough to protect you. When you ask them for something that can’t be done, they care enough about you to tell you the truth. It’s not that they don’t want to get it done, they know they cannot. And they’re willing to tell you to your face. Type II people don’t care about you as a leader; they only care about themselves. They say yes when they know the answer is no. And they do it in a way that absolves them of responsibility when the wheels fall off. As a leader, which type do you want on your team? And as a leader, which type do you promote and which do you chastise. And, how do you feel about that?

As a leader, you must be truthful. And when you can’t disclose the full truth, tell people. And when your Type II direct reports give you the answer they know you want to hear, call them on their bullshit. And when your Type III folks give you the answer they know you don’t want to hear, thank them.

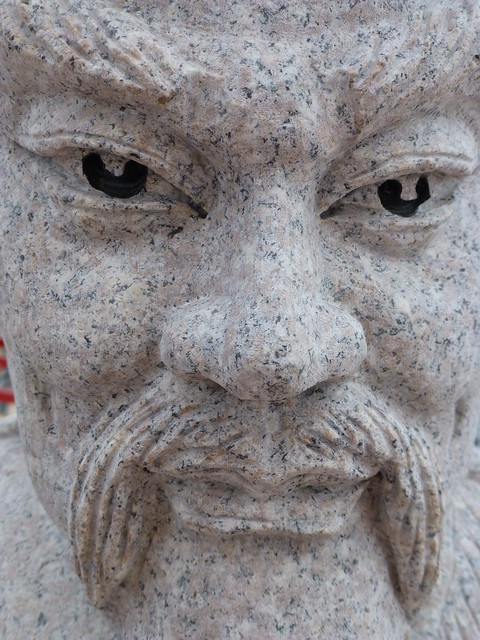

Image credit — Anandajoti Bhikkhu

Wanting things to be different

Wanting things to be different is a good start, but it’s not enough. To create conditions for things to move in a new direction, you’ve got to change your behavior. But with systems that involve people, this is not a straightforward process.

To create conditions for the system to change, you must understand the system”s disposition – the lines along which it prefers to change.. And to do that, you’ve got to push on the system and watch its response. With people systems, the response is not knowable before the experiment.

If you expect to be able to predict how the system will respond, working with people systems can be frustrating. I offer some guidance here. With this work, you are not responsible for the system’s response, you are only responsible for how you respond to the system’s response.

If the system responds in a way you like, turn that experiment into a project to amplify the change. If the system responds in a way you dislike, unwind the experiment. Here’s a simple mantra – do more of what works and less of what doesn’t. (Thanks to Dave Snowden for this.)

If you don’t like how things are going, you have only one lever to pull. You can only change.your response to what you see and experience. You can respond by pushing on the system and responding to what you see or you can respond by changing what you think and feel about the system.

But keep in mind that you are part of the system. And maybe the system is running an experiment on you. Either way, your only choice is to choose how to respond.

Whether it goes well or poorly, what matters is how you respond.

When was the last time you taught someone a new method or technique? What was their reaction? How did it make you feel? Will you do it again?

When was the last time you taught someone a new method or technique? What was their reaction? How did it make you feel? Will you do it again?

When was the last time you learned something new from a colleague? What was your reaction? What did you do so it would happen again?

When was the last time you woke up early because you were excited to go to work? How did you feel about that? What can change so it happens once a week?

When was the last time you had a crazy idea and your colleagues helped you make it real? How did you feel about that? How can you do it for them? What can you do to make it happen more frequently?

When was the last time you had a crazy idea and it was squelched because it violated a successful recipe? How did you feel about that? What can you do so it happens differently next time?

When was the last time you used your good judgement without asking for permission? How did you feel about that? What can you do to give others the confidence to use their best judgement?

When was the last time someone gave you credit for doing good work? And when was the last time you did the same for someone else? What can you do so the behavior blossoms into common practice?

When was the last time you openly contradicted a majority opinion with a dissenting minority opinion? Though it was received poorly, you must do it again. The majority needs to hear your dissenting opinion so they can sharpen their thinking.

When was the last time you gave good advice to a younger colleague? How can you systematize that type of behavior?

When was the last time you did work so undeniably good that others twisted it a bit and adopted it as their own? Don’t feel badly. When doing innovative work this is what success looks like. All that really matters is your customers realize the value from the work and not who gets credit. What can you do so this type of thing happens as a matter of course?

Good things happen and bad things happen. That’s how life goes. But the important part is you pay attention to what worked and what didn’t. And the second important part is actively making the good stuff happen more frequently and the bad stuff happen less frequently.

Image credit — jacquemart

Business is about feelings and emotions.

If you use your sane-and-rational lenses and the situation doesn’t make sense, that’s because the situation is not governed by sanity and rationality. Yet, even though there’s a mismatch between the system’s behavior and sane-and-rational, we still try to understand the system through the cloudy lenses of sanity and rationality.

If you use your sane-and-rational lenses and the situation doesn’t make sense, that’s because the situation is not governed by sanity and rationality. Yet, even though there’s a mismatch between the system’s behavior and sane-and-rational, we still try to understand the system through the cloudy lenses of sanity and rationality.

Computer programs are sane and rational; Algorithms are sane and rational; Machines are sane and rational. Fixed inputs yield predicted outputs; If this, then that; Repeat the experiment and the results are repeated. In the cold domain of machines, computer programs and algorithms you may not like the output, but you’re not surprised by it.

But businesses are not run by computer programs, algorithms and machines. Businesses are run by people. And that’s why things aren’t always sane and rational in business.

Where computer programs blindly follow logic that’s coded into them, people follow their emotions. Where algorithms don’t decide what to do based on their emotional state, people do. And where machines aren’t afraid to try something new, people are.

When something doesn’t make sense to you, it’s because your assumptions about the underlying principles are wrong. If you see things that violate logic, it’s because logic isn’t the guiding principle. And if logic isn’t the guiding principle, the only other things that could be driving the irrationality are feelings and emotions. But if you think the solution is to make the irrational system behave rationally, be prepared to be perplexed and frustrated.

The underpinnings of management and leadership are thoughts, feelings and emotions. And, thoughts are governed by feelings and emotions. In that way, the currency of management and leadership is feelings and emotions.

If your first inclination is to figure out a situation using logic, don’t. Logic is for computers, and even that’s changing with deep learning. Business is about people. When in doubt, assess the feelings and emotions of the people involved. And once you understand their thoughts and feelings, you’ll know what to do.

Business isn’t about algorithms. Business is about people. And people respond based on their emotional state. If you want to be a good manager, focus on people’s feelings and emotions. And if you want to be a good leader, do the same.

Image credit: Guiseppe Milo

On Gumption

Doing new work takes gumption. But there are two problems with gumption. One, you’ve got to create it from within. Two, it takes a lot of energy to generate the gumption and to do that you’ve got to be physically fit and mentally grounded. Here are some words that may help.

Doing new work takes gumption. But there are two problems with gumption. One, you’ve got to create it from within. Two, it takes a lot of energy to generate the gumption and to do that you’ve got to be physically fit and mentally grounded. Here are some words that may help.

Move from self-judging to self-loving. It makes a difference.

It’s never enough until you decide it’s enough. And when you do, you can be more beholden to yourself.

You already have what you’re looking for. Look inside.

Taking care of yourself isn’t selfish, it’s self-ful.

When in doubt, go outside.

You can’t believe in yourself without your consent.

Your well-being is your responsibility. And it’s time to be responsible.

When you move your body, your mind smiles.

With selfish, you take care of yourself at another’s expense. With self-ful, you take care of yourself because you’re full of self-love.

When in doubt, feel the doubt and do it anyway.

If you’re not taking care of yourself, understand what you’re putting in the way and then don’t do that anymore.

You can’t help others if you don’t take care of yourself.

If you struggle with taking care of yourself, pretend you’re someone else and do it for them.

Image credit — Ramón Portellano

Healthy Dissatisfaction

If you’re dissatisfied, there’s a reason.

If you’re dissatisfied, there’s a reason.

If you’re dissatisfied, there’s hope for us all.

If you’re not dissatisfied, there’s no forcing function for change.

If you’re not dissatisfied, the status quo will carry the day.

If you’re not dissatisfied, innovation work is not for you.

If you’re dissatisfied, you know it could be better next time.

If you’re dissatisfied, your insecure leader will step on your head.

If you’re dissatisfied, there’s a reason and that reason is real.

If you’re dissatisfied, follow your dissatisfaction.

If you’re dissatisfied, I want to work with you.

If you’re dissatisfied, it’s because you see things as they are.

If you’re dissatisfied, your confident leader will ask how things should go next time.

If you’re dissatisfied, it’s because you want to make a difference.

If you’re dissatisfied, look inside.

If you’re dissatisfied, there’s a reason, the reason is real and it’s time to do something about it.

If you’re dissatisfied, you’re thinking for yourself.

If you’re so dissatisfied you openly show anger, thank you for trusting me enough to show your true self.

If you’re dissatisfied, it’s because you know things should be better than they are.

If you’re dissatisfied, do something about it.

If you’re dissatisfied, thank you for thinking deeply.

If you’re dissatisfied, it’s because you’re not asleep at the wheel.

If you’re dissatisfied, it’s because your self-worth allows it.

Thank you for caring enough to be dissatisfied.

Image credit – Vinod Chandar

For innovation to flow, drive out fear.

The primary impediment to innovation is fear, and the prime directive of any innovation system should be to drive out fear.

A culture of accountability, implemented poorly, can inject fear and deter innovation. When the team is accountable to deliver on a project but are constrained to a fixed scope, a fixed launch date and resources, they will be afraid. Because they know that innovation requires new work and new work is inherently unpredictable, they rightly recognize the triple accountability – time, scope and resources – cannot be met. From the very first day of the project, they know they cannot be successful and are afraid of the consequences.

A culture of accountability can be adapted to innovation to reduce fear. Here’s one way. Keep the team small and keep them dedicated to a single innovation project. No resource sharing, no swapping and no double counting. Create tight time blocks with clear work objectives, where the team reports back on a fixed pitch (weekly, monthly). But make it clear that they can flex on scope and level of completeness. They should try to do all the work within the time constraints but they must know that it’s expected the scope will narrow or shift and the level of completeness will be governed by the time constraint. Tell them you believe in them and you trust them to do their best, then praise their good judgement at the review meeting at the end of the time block.

Innovation is about solving new problems, yet fear blocks teams from trying new things. Teams like to solve problems that are familiar because they have seen previous teams judged negatively for missing deadlines. Here’s the logic – we’d rather add too little novelty than be late. The team would love to solve new problems but their afraid, based on past projects, that they’ll be chastised for missing a completion date that’s disrespectful of the work content and level of novelty. If you want the team to solve new problems, give them the tools, time, training and a teacher so they can select different problems and solve them differently. Simply put – create the causes and conditions for fear to quietly slink away so innovation will flow.

Fear is the most powerful inhibitor. But before we can lessen the team’s fear we’ve got to recognize the causes and conditions that create it. Fear’s job is to keep us safe, to keep us away from situations that have been risky or dangerous. To do this, our bodies create deep memories of those dangerous or scary situations and creates fear when it recognizes similarities between the current situation and past dangerous situations. In that way, less fear is created if the current situation feels differently from situations of the past where people were judged negatively.

To understand the causes and conditions that create fear, look back at previous projects. Make a list of the projects where project members were judged negatively for things outside their control such as: arbitrary launch dates not bound by the work content, high risk levels driven by unjustifiable specifications, insufficient resources, inadequate tools, poor training and no teacher. And make a list of projects where team members were praised. For the projects that praised, write down attributes of those projects (e.g., high reuse, low technical risk) and their outcomes (e.g., on time, on cost). To reduce fear, the project team will bend new projects toward those attributes and outcomes. Do the same for projects that judged negatively for things outside the project teams’ control. To reduce fear, the future project teams will bend away from those attributes and outcomes.

Now the difficult parts. As a leader, it’s time to look inside. Make a list of your behaviors that set (or contributed to) causes and conditions that made it easy for the project team to be judged negatively for the wrong reasons. And then make a list of your new behaviors that will create future causes and conditions where people aren’t afraid to solve new problems in new ways.

Image credit — andrea floris

The people part is the hardest part.

The toughest part of all things is the people part.

The toughest part of all things is the people part.

Hold on to being right and all you’ll be is right. Transcend rightness and get ready for greatness.

Embrace hubris and there’s no room for truth. Embrace humbleness and everyone can get real.

Judge yourself and others will pile on. Praise others and they will align with you.

Expect your ideas to carry the day and they won’t. Put your ideas out there lightly and ask for feedback and your ideas will grow legs.

Fight to be right and all you’ll get is a bent nose and bloody knuckles. Empathize and the world is a different place.

Expect your plan to control things and the universe will have its way with you. See your plan as a loosely coupled set of assumptions and the universe will still have its way with you.

Argue and you’ll backslide. Appreciate and you’ll ratchet forward.

See the two bad bricks in the wall and life is hard. See the other nine hundred and ninety-eight and everything gets lighter.

Hold onto success and all you get is rope burns. Let go of what worked and the next big thing will find you.

Strive and get tired. Thrive and energize others.

The people part may be the toughest part, but it’s the part that really matters.

Image credit — Arian Zwegers

The Slow No

When there’s too much to do and too few to do it, the natural state of the system is fuller than full. And in today’s world we run all our systems this way, including our people systems.

When there’s too much to do and too few to do it, the natural state of the system is fuller than full. And in today’s world we run all our systems this way, including our people systems.

A funny thing happens when people’s plates are full – when a new task is added an existing one hits the floor. This isn’t negligence, it’s not the result of a bad attitude and it’s not about being a team player. This is an inherent property of full plates – they cannot support a new task without another sliding off. And drinking glasses have this same interesting property – when full, adding more water just gets the floor wet.

But for some reason we think people are different. We think we can add tasks without asking about free capacity and still expect the tasks to get done. What’s even more strange – when our people tell us they cannot get the work done because they already have too much, we don’t behave like we believe them. We say things like “Can you do more things in parallel?” and “Projects have natural slow phases, maybe you can do this new project during the slow times.” Let’s be clear with each other – we’re all overloaded, there are no slow times.

For a long time now, we’ve told people we don’t want to hear no. And now, they no longer tell us. They still know they can’t get the work done, but they know not to use the word “no.” And that’s why the Slow No was invented.

The Slow No is when we put a new project on the three year road map knowing full-well we’ll never get to it. It’s not a no right now, it’s a no three years from now. It’s elegant in its simplicity. We’ll put it on the list; we’ll put it in the queue; we’ll put it on the road map. The trick is to follow normal practices to avoid raising concerns or drawing attention. The key to the Slow No is to use our existing planning mechanisms in perfectly acceptable ways.

There’s a big downside to the Slow No – it helps us think we’ve got things under control when we don’t. We see a full hopper of ideas and think our future products will have sizzle. We see a full road map and think we’re going to have a huge competitive advantage over our competitors. In both situations, we feel good and in both situations, we shouldn’t. And that’s the problem. The Slow No helps us see things as we want them and blocks us from seeing them as they are.

The Slow No is bad for business, and we should do everything we can to get rid of it. But, it’s engrained behavior and will be with us for the near future. We need some tools to battle the dark art of the Slow No.

The Slow No gives too much value to projects that are on the list but inactive. We’ve got to elevate the importance of active, fully-staffed projects and devalue all inactive projects. Think – no partial credit. If a project is active and fully-staffed, it gets full credit. If it’s inactive (on a list, in the queue, or on the road map) it gets zero credit. None. As a project, it does not exist.

To see things as they are, make a list of the active, fully-staffed projects. Look at the list and feel what you feel, but these are the only projects that matter. And for the road map, don’t bother with it. Instead, think about how to finish the projects you have. And when you finish one, start a new one.

The most difficult element of the approach is the valuation of active but partially-staffed projects. To break the vice grip of the Slow No, think no partial credit. The project is either fully-staffed or it isn’t And if it’s not fully-staffed, give the project zero value. None. I know this sounds outlandish, but the partially-staffed project is the slippery slope that gives the Slow No its power.

For every fully-staffed project on your list, define the next project you’ll start once the current one is finished. Three active projects, three next projects. That’s it. If you feel the need to create a road map, go for it. Then, for each active project, use the road map to choose the next projects. Again, three active projects, three next projects. And, once the next projects are selected, there’s no need to look at the road map until the next projects are almost complete.

The only projects that truly matter are the ones you are working on.

Image credit – DaPuglet

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski