Archive for the ‘Culture’ Category

The only thing predictable about innovation is its unpredictability.

A culture that demands predictable results cannot innovate. No one will have the courage to do work with the requisite level of uncertainty and all the projects will build on what worked last time. The only predictable result – the recipe will be wildly successful right up until the wheels fall off.

A culture that demands predictable results cannot innovate. No one will have the courage to do work with the requisite level of uncertainty and all the projects will build on what worked last time. The only predictable result – the recipe will be wildly successful right up until the wheels fall off.

You can’t do work in a new area and deliver predictable results on a predictable timetable. And if your boss asks you to do so, you’re working for the wrong person.

When it comes to innovation, “ecosystem,” as a word, is unskillful. It doesn’t bound or constrain, nor does it show the way. How about a map of the system as it is? How about defined boundaries? How about the system’s history? How about the interactions among the system elements? How about a fitness landscape and the system’s disposition? How about the system’s reason for being? The next evolution of the system is unpredictable, even if you call it an ecosystem.

If you can’t tolerate unpredictability, you can’t tolerate innovation.

Innovation isn’t about reducing risk. Innovation is about maximizing learning rate. And when all things go as predicted, the learning rate is zero. That’s right. Learning decreases when everything goes as planned. Are you sure you want predictable results?

Predictable growth in stock price can only come from smartly trying the right portfolio of unpredictable projects. That’s a wild notion.

Innovation runs on the thoughts, feelings, emotions and judgement of people and, therefore, cannot be predictable. And if you try to make it predictable, the best people, the people that know the drill, will leave.

The real question that connects innovation and predictability: How to set the causes and conditions for people to try things because the results are unpredictable?

With innovation, if you’re asking for predictability, you’re doing it wrong.

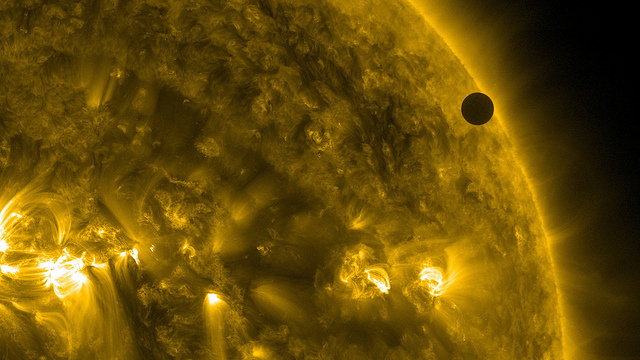

Image credit: NASA Goddard

For innovation to flow, drive out fear.

The primary impediment to innovation is fear, and the prime directive of any innovation system should be to drive out fear.

A culture of accountability, implemented poorly, can inject fear and deter innovation. When the team is accountable to deliver on a project but are constrained to a fixed scope, a fixed launch date and resources, they will be afraid. Because they know that innovation requires new work and new work is inherently unpredictable, they rightly recognize the triple accountability – time, scope and resources – cannot be met. From the very first day of the project, they know they cannot be successful and are afraid of the consequences.

A culture of accountability can be adapted to innovation to reduce fear. Here’s one way. Keep the team small and keep them dedicated to a single innovation project. No resource sharing, no swapping and no double counting. Create tight time blocks with clear work objectives, where the team reports back on a fixed pitch (weekly, monthly). But make it clear that they can flex on scope and level of completeness. They should try to do all the work within the time constraints but they must know that it’s expected the scope will narrow or shift and the level of completeness will be governed by the time constraint. Tell them you believe in them and you trust them to do their best, then praise their good judgement at the review meeting at the end of the time block.

Innovation is about solving new problems, yet fear blocks teams from trying new things. Teams like to solve problems that are familiar because they have seen previous teams judged negatively for missing deadlines. Here’s the logic – we’d rather add too little novelty than be late. The team would love to solve new problems but their afraid, based on past projects, that they’ll be chastised for missing a completion date that’s disrespectful of the work content and level of novelty. If you want the team to solve new problems, give them the tools, time, training and a teacher so they can select different problems and solve them differently. Simply put – create the causes and conditions for fear to quietly slink away so innovation will flow.

Fear is the most powerful inhibitor. But before we can lessen the team’s fear we’ve got to recognize the causes and conditions that create it. Fear’s job is to keep us safe, to keep us away from situations that have been risky or dangerous. To do this, our bodies create deep memories of those dangerous or scary situations and creates fear when it recognizes similarities between the current situation and past dangerous situations. In that way, less fear is created if the current situation feels differently from situations of the past where people were judged negatively.

To understand the causes and conditions that create fear, look back at previous projects. Make a list of the projects where project members were judged negatively for things outside their control such as: arbitrary launch dates not bound by the work content, high risk levels driven by unjustifiable specifications, insufficient resources, inadequate tools, poor training and no teacher. And make a list of projects where team members were praised. For the projects that praised, write down attributes of those projects (e.g., high reuse, low technical risk) and their outcomes (e.g., on time, on cost). To reduce fear, the project team will bend new projects toward those attributes and outcomes. Do the same for projects that judged negatively for things outside the project teams’ control. To reduce fear, the future project teams will bend away from those attributes and outcomes.

Now the difficult parts. As a leader, it’s time to look inside. Make a list of your behaviors that set (or contributed to) causes and conditions that made it easy for the project team to be judged negatively for the wrong reasons. And then make a list of your new behaviors that will create future causes and conditions where people aren’t afraid to solve new problems in new ways.

Image credit — andrea floris

You can’t innovate when…

Your company believes everything should always go as planned.

You still have to do your regular job.

The project’s completion date is disrespectful of the work content.

Your company doesn’t recognize the difference between complex and complicated.

The team is not given the tools, training, time and a teacher.

You’re asked to generate 500 ideas but you’re afraid no one will do anything with them.

You’re afraid to make a mistake.

You’re afraid you’ll be judged negatively.

You’re afraid to share unpleasant facts.

You’re afraid the status quo will be allowed to squash the new ideas, again.

You’re afraid the company’s proven recipe for success will stifle new thinking.

You’re afraid the project team will be staffed with a patchwork of part time resources.

You’re afraid you’ll have to compete for funding against the existing business units.

You’re afraid to build a functional prototype because the value proposition is poorly defined.

Project decisions are consensus-based.

Your company has been super profitable for a long time.

The project team does not believe in the project.

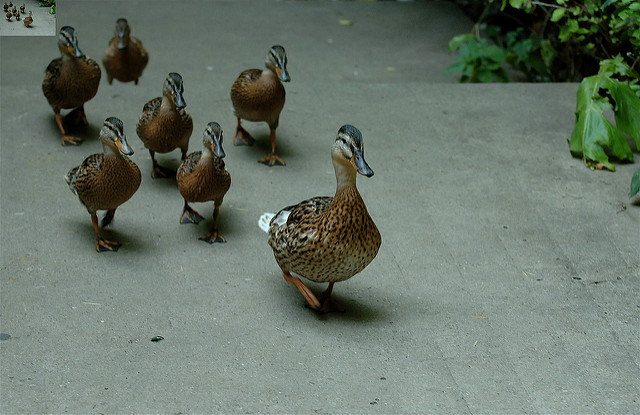

Image credit Vera & Gene-Christophe

The Four Ways to Run Projects

There are four ways to run projects.

There are four ways to run projects.

One – 80% Right, 100% Done, 100% On Time, 100% On Budget

- Fix time

- Fix resources

- Flex scope and certainty

Set a tight timeline and use the people and budget you have. You’ll be done on time, but you must accept a reduced scope (fewer bells and whistles) and less certainty of how the product/service will perform and how well it will be received by customers. This is a good way to go when you’re starting a new adventure or investigating new space.

Two – 100% Right, 100% Done, 0% On Time, 0% On Budget

- Fix resources

- Fix scope and certainty

- Flex time

Use the team and budget you have and tightly define the scope (features) and define the level of certainty required by your customers. Because you can’t predict when the project will be done, you’ll be late and over budget, but your offering will be right and customers will like it. Use this method when your brand is known for predictability and stability. But, be weary of business implications of being late to market.

Three – 100% Right, 100% Done, 100% On Time, 0% On Budget

- Fix scope and certainty

- Fix time

- Flex resources

Tightly define the scope and level of certainty. Your customers will get what they expect and they’ll get it on time. However, this method will be costly. If you hire contract resources, they will be expensive. And if you use internal resources, you’ll have to stop one project to start this one. The benefits from the stopped project won’t be realized and will increase the effective cost to the company. And even though time is fixed, this approach will likely be late. It will take longer than planned to move resources from one project to another and will take longer than planned to hire contract resources and get them up and running. Use this method if you’ve already established good working relationships with contract resources. Avoid this method if you have difficulty stopping existing projects to start new ones.

Four – Not Right, Not Done, Not On Time, Not On Budget

- Fix time

- Fix resources

- Fix scope and certainty

Though almost every project plan is based on this approach, it never works. Sure, it would be great if it worked, but it doesn’t, it hasn’t and it won’t. There’s not enough time to do the right work, not enough money to get the work done on time and no one is willing to flex on scope and certainty. Everyone knows it won’t work and we do it anyway. The result – a stressful project that doesn’t deliver and no one feels good about.

Image credit – Cees Schipper

The people part is the hardest part.

The toughest part of all things is the people part.

The toughest part of all things is the people part.

Hold on to being right and all you’ll be is right. Transcend rightness and get ready for greatness.

Embrace hubris and there’s no room for truth. Embrace humbleness and everyone can get real.

Judge yourself and others will pile on. Praise others and they will align with you.

Expect your ideas to carry the day and they won’t. Put your ideas out there lightly and ask for feedback and your ideas will grow legs.

Fight to be right and all you’ll get is a bent nose and bloody knuckles. Empathize and the world is a different place.

Expect your plan to control things and the universe will have its way with you. See your plan as a loosely coupled set of assumptions and the universe will still have its way with you.

Argue and you’ll backslide. Appreciate and you’ll ratchet forward.

See the two bad bricks in the wall and life is hard. See the other nine hundred and ninety-eight and everything gets lighter.

Hold onto success and all you get is rope burns. Let go of what worked and the next big thing will find you.

Strive and get tired. Thrive and energize others.

The people part may be the toughest part, but it’s the part that really matters.

Image credit — Arian Zwegers

A Little Uninterrupted Work Goes a Long Way

If your day doesn’t start with a list of things you want to get done, there’s little chance you’ll get them done. What if you spent thirty minutes to define what you want to get done and then spent an hour getting them done? In ninety minutes you’ll have made a significant dent in the most important work. It doesn’t sound like a big deal, but it’s bigger than big. Question: How often do you work for thirty minutes without interruptions?

If your day doesn’t start with a list of things you want to get done, there’s little chance you’ll get them done. What if you spent thirty minutes to define what you want to get done and then spent an hour getting them done? In ninety minutes you’ll have made a significant dent in the most important work. It doesn’t sound like a big deal, but it’s bigger than big. Question: How often do you work for thirty minutes without interruptions?

Switching costs are high, but we don’t behave that way. Once interrupted, what if it takes ten minutes to get back into the groove? What if it takes fifteen minutes? What if you’re interrupted every ten or fifteen minutes? Question: What if the minimum time block to do real thinking is thirty minutes of uninterrupted time?

Let’s assume for your average week you carve out sixty minutes of uninterrupted time each day to do meaningful work, then, doing as I propose – spending thirty minutes planning and sixty minutes doing something meaningful every day – increases your meaningful work by 50%. Not bad. And if for your average week you currently spend thirty contiguous minutes each day doing deep work, the proposed ninety-minute arrangement increases your meaningful work by 200%. A big deal. And if you only work for thirty minutes three out of five days, the ninety-minute arrangement increases your meaningful work by 400%. A night and day difference.

Question: How many times per week do you spend thirty minutes of uninterrupted time working on the most important things? How would things change if every day you spent thirty minutes planning and sixty minutes doing the most important work?

Great idea, but with today’s business culture there’s no way to block out ninety minutes of uninterrupted time. To that I say, before going to work, plan for thirty minutes at home. And set up a sixty-minute recurring meeting with yourself first thing every morning and do sixty minutes of uninterrupted work. And if you can’t sit at your desk without being interrupted, hold the sixty-minute meeting with yourself in a location where you won’t be interrupted. And, to make up for the thirty minutes you spent planning at home, leave thirty minutes early.

No way. Can’t do it. Won’t work.

It will work. Here’s why. Over the course of a month, you’ll have done at least 50% more real work than everyone else. And, because your work time is uninterrupted, the quality of your work will be better than everyone else’s. And, because you spend time planning, you will work on the most important things. More deep work, higher quality working conditions, and regular planning. You can’t beat that, even if it’s only sixty to ninety minutes per day.

The math works because in our normal working mode, we don’t spend much time working in an uninterrupted way. Do the math for yourself. Sum the number of minutes per week you spend working at least thirty minutes at time. And whatever the number, figure out a way to increase the minutes by 50%. A small number of minutes will make a big difference.

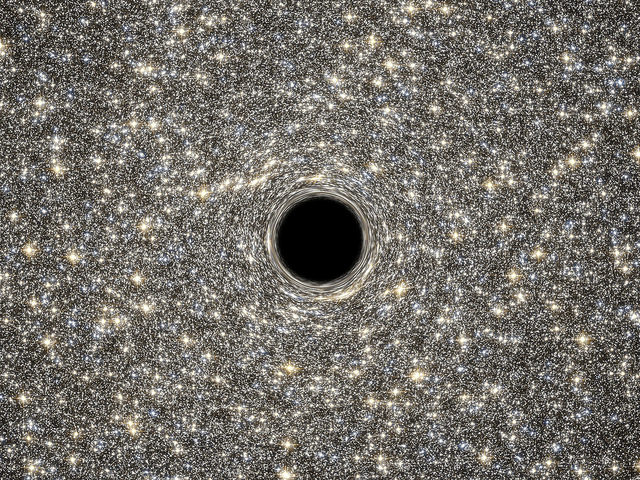

Image credit – NASA Goddard Space Flight Center

Everyday Leadership

What if your primary role every day was to put other people in a position to succeed? What would you start doing? What would you stop doing? Could you be happy if they got the credit and you didn’t? Could you feel good about their success or would you feel angry because they were acknowledged for their success? What would happen if you ran the experiment?

What if your primary role every day was to put other people in a position to succeed? What would you start doing? What would you stop doing? Could you be happy if they got the credit and you didn’t? Could you feel good about their success or would you feel angry because they were acknowledged for their success? What would happen if you ran the experiment?

What if each day you had to give ten compliments? Could you notice ten things worthy of compliment? Could you pay enough attention? Would it be difficult to give the compliments? Would it be easy? Would it scare you? Would you feel silly or happy? Who would be the first person you’d compliment? Who is the last person you’d compliment? How would they feel? What could it hurt to try it for a week?

What if each day you had to ask five people if you can help them? Could you do it even for one day? Could you ask in a way the preserves their self-worth? Could you ask in a sincere way? How do you think they would feel if you asked them? How would you feel if they said yes? How about if they said no? Would the experiment be valuable? Would it be costly? What’s in the way of trying it for a day? How do you feel about what’s in the way?

What if you made a mistake and you had to apologize to five people? Could you do it? Would you do it? Could you say “I’m sorry. I won’t do it again. How can I make it up to you?” and nothing else? Could you look them in the eye and apologize sincerely? If your apology was sincere, how would they feel? And how would you feel? Next time you make a mistake, why not try to apologize like you mean it? What could it hurt? Why not try?

What if every day you had to thank five people? Could you find five things to be thankful for? Would you make the effort to deliver the thanks face-to-face? Could you do it for two days? Could you do it for a week? How would you feel if you actually did it for a week? How would the people around you feel? How do you feel about trying it?

What if every day you tried to be a leader?

Image credit – Pedro Ribeiro Simões

Creating the Causes and Conditions for New Behavior to Grow

When you see emergent behavior that could grow into a powerful new theme, it’s important to acknowledge the behavior quickly and most publicly. If you see it in person, praise the behavior in front of everyone. Explain why you like it, explain why it’s important, explain what it could become. And as soon as you can find a computer, send an email to their bosses and copy the right-doers. Tell their bosses why you like it, tell them why it’s important, tell them what it could become.

When you see emergent behavior that could grow into a powerful new theme, it’s important to acknowledge the behavior quickly and most publicly. If you see it in person, praise the behavior in front of everyone. Explain why you like it, explain why it’s important, explain what it could become. And as soon as you can find a computer, send an email to their bosses and copy the right-doers. Tell their bosses why you like it, tell them why it’s important, tell them what it could become.

Emergent behavior is like the first shoots of a beautiful orchid that may come to be. To the untrained eye, these little green beauties can look like scraggly weeds pushing out of the dirt. To the tired, overworked leader these new behaviors can like divergence, goofing around and even misbehavior. Without studying the leaves, the fledgling orchid can be confused for crabgrass.

Without initiative there is no new behavior and without new behavior there can be no orchids. When good people solve a problem in a creative way and it goes unacknowledged, the stem of the emergent behavior is clipped. But when the creativity is watered and fertilized the seedling has a chance to grow into something more. The leaders’ time and attention provide the nutrients, the leaders’ praise provides the hydration and their proactive advocacy for more of the wonderful behavior provides the sunlight to fuel the photosynthesis.

When the company demands bushels of grain, it’s a challenge to keep an eye out for the early signs of what could be orchids in the making. But that’s what a leader must do. More often than not, this emergent behavior, this magical behavior, goes unacknowledged if not unnoticed. As leaders, this behavior is unskillful. As leaders, we’ve got to slow down and pay more attention.

When you see the magic in emergent behavior, when you see the revolution it could grow into, and when you look someone in the eye and say – “I’ve got to tell you, what you did was crazy good. What you did could turn things upside down. What you did was inspiring. Thank you.” – you get people’s attention. Not only to do you get the attention of the person you’re talking to, you get the attention of everyone within a ten-foot radius. And thirty minutes later, almost everyone knows about the emergent behavior and the warm sunshine it attracted.

And, magically, without a corporate initiative or top-down deployment, over the next weeks there will be patches of orchids sprouting under desks, behind filing cabinets, on the manufacturing floor, in the engineering labs and in the common areas.

As leaders we must make it easier for new behavior to happen. We must figure a way to slow down and pay attention so we can recognize the seeds of could-be greatness. And to be able to invest the emotional energy needed to protect the seedlings, we must be well-rested. And like we know to provide the right soil, the right fertilizer, the right watering schedule and the right sunlight, we must remember that special behavior we want to grow is a result of causes and conditions we create.

Image credit – Rosemarie Crisasfi

The Leader’s Journey

If you know what to do, do it. Don’t ask, just do.

If you know what to do, do it. Don’t ask, just do.

If you’re pretty sure what to do, do it. Don’t ask, just do.

If you think you may know what to do, do it. Don’t ask, just do.

If you don’t know what to do, try something small. Then, do more of what works and less of what doesn’t.

If your team doesn’t know what to do unless they ask you, tell them to do what they think is right. And tell them to stop asking you what to do.

If your team won’t act without your consent, tell them to do what they think is right. Then, next time they seek your consent, be unavailable.

If the team knows what to do and they go around you because they know you don’t, praise them for going around you. Then, set up a session where they educate you on what you should know.

If the team knows what to do and they know you don’t, but they don’t go around you because they are too afraid, apologize to them for creating a fear-based culture and ask them to do what they think is right. Then, look inside to figure out how to let go of your insecurities and control issues.

If your team needs your support, support them.

If your team need you to get out of the way, go home early.

If your team needs you to break trail, break it.

If they need to see how it should go, show them.

If they need the rules broken, break them.

If they need the rules followed, follow them.

If they need to use their judgement, create the causes and conditions for them to use their judgement.

If they try something new and it doesn’t go as anticipated, praise them for trying something new.

If they try the same thing a second time and they get the same results and those results are still unanticipated, set up a meeting to figure out why they thought the same experiment would lead to different results.

Try to create the team that excels when you go on vacation.

Better yet, try to create the team that performs extremely well when you’re involved in the work and performs even better when you’re on vacation. Then, because you know you’ve prepared them for the future, happily move on to your next personal development opportunity.

Image credit — Puriri deVry

Allocating resources as if people and planet mattered.

Business is about allocating resources to achieve business objectives. And for that, the best place to start is to define the business objectives.

Business is about allocating resources to achieve business objectives. And for that, the best place to start is to define the business objectives.

First – what is the timeframe of the business objectives? Well, there are three – short, medium and long. Short is about making payroll, shipping this month’s orders and meeting this year’s sales objectives. Long is about the existence of the company over the next decade and happiness of the people that do the work along the way. And medium – the toughest – is in-between. It’s neither short nor long but bound by both.

Second – define business objectives within the three types: people, planet and profit.

People. Short term: pay them so they can eat, pay the mortgage and fund their retirement, provide healthcare, provide a safe workplace, give them work that fits their strengths and give them time to improve their community. Medium: pay them so they can provide for their family and fund their retirement, provide healthcare, provide a safer workplace, give them work that requires them to grow their strengths and give them time to become community leaders. Long: pay them so they can pay for their kids’ college and know they can safely retire, provide the safest workplace, let them choose their own work, and give them time to grow the next community leaders. And make it easy.

Planet. Short term: teach Life Cycle Assessment, Buddhist Economics and TRIZ and create business metrics for them to flourish. Medium: move from global sourcing to local sourcing, move to local production, move from business models based on non-renewable resources to renewable resources. Long: create new business models that are resource neutral. Longer: create business models that generate excess resources. Longest: teach others.

Profit. Short, medium and long – focus on people and planet and the profits will come. But also focus on creating new value for new customers.

For business objectives, here’s the trick on timeframe – always work short term, always work long term and prioritize medium term.

And for the three types of business objectives, focus on people, planet and creating new value for new customers. Profits are a result.

Image credit – magnetismus

Make It Easy

When you push, you make it easy for people resist. When you break trail, you make it easy for them to follow.

When you push, you make it easy for people resist. When you break trail, you make it easy for them to follow.

Efficiency is overrated, especially when it interferes with effectiveness. Make it easy for effectiveness to carry the day.

You can push people off a cliff or build them a bridge to the other side. Hint – the bridge makes it easy.

Even new work is easy when people have their own reasons for doing it.

Making things easier is not easy.

Don’t tell people what to do. Make it easy for them to use their good judgement.

Set the wrong causes and conditions and creativity screeches to a halt. Set the right ones and it flows easily. Creativity is a result.

Don’t demand that people pull harder, make it easier for them to pull in the same direction.

Activity is easy to demonstrate and progress isn’t. Figure out how to make progress easier to demonstrate.

The only way to make things easier is to try to make them easier.

Image credit – Richard Hurd

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski