Archive for the ‘Culture’ Category

Don’t mentor. Develop young talent.

Your young talent deserves your attention. But it’s not for the sake of the young talent, it’s for the survival of your company.

Your young talent deserves your attention. But it’s not for the sake of the young talent, it’s for the survival of your company.

Your young talent understands technology far better than your senior leaders. And they don’t just know how it works, they know why people use it. And it’s not just social media. They know how to code, they know how to prototype (I think the call it hacking, or something like that.) and they know how things fit together. And they know what’s next. But they don’t know how to get things done within your organization.

Mentoring isn’t the right word. It’s a tired word without meaning, and we’ve demonstrated we care about it only from a compliance standpoint and not a content standpoint. The mentorship checklist – set up regular meetings, meet infrequently without an agenda, lie it die a slow death and then declare compliance. Nurturing is a better word, but it has connotations of taking care. Parenting captures the essence of the work, but it doesn’t fit with the language of companies. But that may not be so bad, because the work doesn’t fit with the operations companies.

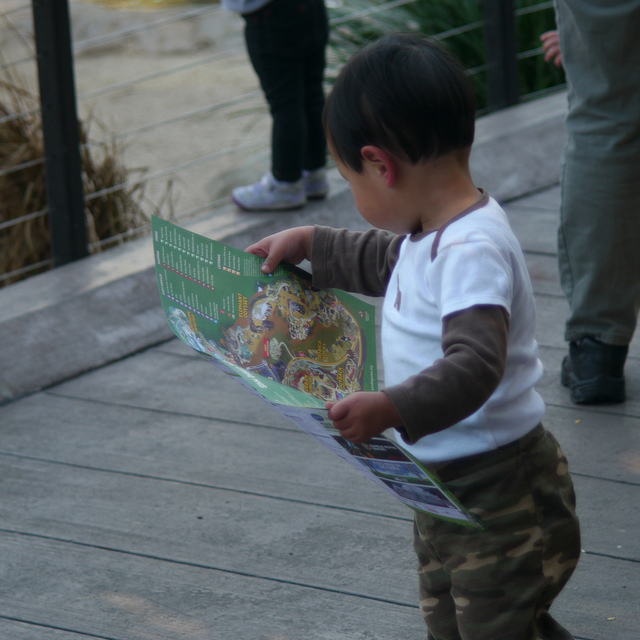

In the short term it’s inefficient to spend precious leadership bandwidth on young talent, but in the long run, it’s the only way to go. Just as the yardwork goes more slowly when your kids help, the next time it’s a bit faster. But the real benefit, the unquantifiable benefit, is the pure joy of spending time with irreverent, energetic, idealistic young people. Yes, there’s less productivity (fewer leaves raked per hour), but that’s not what it’s about. There’s growth, increased capability and shared experience that will set up the next lesson.

The biggest mistake is to come up with special “mentorship projects”. Adding work for the sake of growing talent is wrong on so many levels. Instead, help them with the work they’re expected to do. Dig in. Help them. Contribute to their projects. Go to their meetings. Provide technical guidance. Look ahead for potential problems and tell them they are looming over the horizon. Let them make the decisions. Let them choose the path, but run ahead and make sure they negotiate the corner. If they’re going to make it, let them scoot through without them seeing you. If they’re going to crash, grab the wheel and negotiate the corner with them. Then, when things have calmed down, tell them why you stepped in.

Your children watch you. They watch how you interact with your spouse; they watch how you handle stressful situations; they watch how you treat other children; they listen to what you say to them; they listen to how you say it. And when the words disagree with the unsaid sentiment, they believe the sentiment. Your children know you by your actions. You are transparent to them. They know everything about you. They know why you do things and they know what you stand for. And young talent is no different.

There is nothing more invigorating than a bright, young person willing to dig in and make a difference. Their passion is priceless. And as much as you are helping them, they are helping you. They spark new thinking; they help you see the implicit assumptions you’ve left untested for too long and then naively stomp on them and give you a save-face way to revisit your old thinking. When the toddler learns to walk, even the grandparents spring to life and spryly support them step-by-step.

Don’t call it parenting, but behave like one. Take the time to form the close relationships that transcend the generational divide. Make it personal, because it is. And when you have too much to do and too little time to invest in young talent, do it anyway. Do it for them or do it for the company, but do it.

But in the end, do it for the right reason, the selfish reason – because it the best thing for you.

Image credit – mliu92

Step-Wise Learning

At every meeting you have a chance to move things forward or hold them back. When a new idea is first introduced it’s bare-naked. In its prenatal state, it’s wobbly and can’t stand on its own and is vulnerable to attack. But since it’s not yet developed, it’s impressionable and willing to evolve into what it could be. With the right help it can go either way – die a swift death or sprout into something magical.

At every meeting you have a chance to move things forward or hold them back. When a new idea is first introduced it’s bare-naked. In its prenatal state, it’s wobbly and can’t stand on its own and is vulnerable to attack. But since it’s not yet developed, it’s impressionable and willing to evolve into what it could be. With the right help it can go either way – die a swift death or sprout into something magical.

Early in gestation, the most worthy ideas don’t look that way. They’re ugly, ill-formed, angry or threatening. Or, they’re playful, silly or absurd. Depending on your outlook, they can be a member of either camp. And as your outlook changes, they can jump from one camp to the other. Or, they can sit with one leg in each. But none of that is about the idea, it’s all about you. The idea isn’t a thing in itself, it’s a reflection of you. The idea is nothing until you attach your feelings to it. Whether it lives or dies depends on you.

Are you looking for reasons to say yes or reasons to say no?

On the surface, everyone in the organization looks like they’re fully booked with more smart goals than they can digest and have more deliverables than they swallow, but that’s not the case. Though it looks like there’s no room for new ideas, there’s plenty of capacity to chew on new ideas if the team decides they want to. Every team can spare and hour or two a week for the right ideas. The only real question is do they want to?

If someone shows interest and initiative, it’s important to support their idea. The smallest acceptable investment is a follow-on question that positively reinforces the behavior. “That’s interesting, tell me more.” sends the right message. Next, “How do you think we should test the idea?” makes it clear you are willing to take the next step. If they can’t think of a way to test it, help them come up with a small, resource-lite experiment. And if they respond with a five year plan and multi-million dollar investment, suggest a small experiment to demonstrate worthiness of the idea. Sometimes it’s a thought experiment, sometimes it’s a discussion with a customer and sometimes it’s a prototype, but it’s always small. Regardless of the idea, there’s always room for a small experiment.

Like a staircase, a series of small experiments build on each other to create big learning. Each step is manageable – each investment is tolerable and each misstep is survivable – and with each experiment the learning objective is the same: Is the new idea worthy of taking the next step? It’s a step-wise set of decisions to allocate resources on the right work to increase learning. And after starting in the basement, with step-by-step experimentation and flight-by-flight investment, you find yourself on the fifth floor.

This is about changing behavior and learning. Behavior doesn’t change overnight, it changes day-by-day, step-by-step. And it’s the same for learning – it builds on what was learned yesterday. And as long at the experiment is small, there can be no missteps. And it doesn’t matter what the first experiment is all about, as long as you take the first step.

Your team will recognize your new behavior because it respectful of their ideas. And when you respect their ideas, you respect them. Soon enough you will have a team that stands taller and runs small experiments on their own. Their experiments will grow bolder and their learning will curve will steepen. Then, you’ll struggle to keep up with them, and you’ll have them right where you want them.

image credit — Rob Warde

To make a difference, believe in yourself.

When the mainstream products become tired, there’s incentive to replace it, but while sales are good there’s no compelling reason to obsolete your best work. Things that matter start from things that no longer matter.

When the mainstream products become tired, there’s incentive to replace it, but while sales are good there’s no compelling reason to obsolete your best work. Things that matter start from things that no longer matter.

The gestation period for a novel idea to transition to viable technology then to a winning product and the processes to bring it market is longer than anyone wants to admit. If you haven’t done it before it takes twice as long as you think and three times longer than you want. If you stomp on the accelerator once there’s consensus you should, you waited too long.

There’s a simple way to tell it’s time to accelerate. When the status quo sets the cruise control to “coast”, it’s time. When new there’s no time to work on new concepts, that’s coasting. When ROI analyses are required for most everything, that’s coasting. When forward-looking work is cut and cost reduction work is accelerated, that’s a sure sign of coasting.

As soon as you recognize coasting, it’s time to circle the wagons and create an acceleration plan. It’s not across-the-board acceleration, nor is it founded on people working harder or taking on more projects. The plan starts with a business objective and a commitment to add resources to speed things up. If the plan isn’t tied tightly to an important business objective it will miss the mark, and if incremental resources are not applied to the work, it won’t accelerate.

Here’s a rule – if projects and resources don’t change, you haven’t changed anything.

When you can feel the low pressure system in your body and can smell the storm brewing over the horizon, you have an obligation to do something about it. But moving resources and starting projects at the expense of stopping others is emotionally charged work, and the successful organization will reject these changes at every turn. And everyone will think there’s no need to change, but they’ll be wrong.

It’s will be tough going, but your instincts are good and intuition is on-the-mark – there is a storm brewing over the horizon. Push through the discomfort, push through the fear, push through the self-doubt.

It’s time to believe in yourself. It’s the only thing powerful enough to make a difference.

Image credit – Chris Kim

There is no failure, there is only learning.

You’re never really sure how your new project will turn out, unless you don’t try. Not trying is the only way to guarantee certainty – certainty that nothing good will come of it.

You’re never really sure how your new project will turn out, unless you don’t try. Not trying is the only way to guarantee certainty – certainty that nothing good will come of it.

There’s been a lot of talk about creating a culture where failure is accepted. But, failure will never be accepted, and nor should it be. Even the failing forward flavor won’t be tolerated. There’s a skunk-like stink to the word that cannot be cleansed. Failure, as a word, should be struck from the vernacular.

If you have a good plan and you execute it well, there can be no failure. The plan can deliver unanticipated results, but that’s not failure, that’s called learning. If the team runs the same experiment three times in a row, that, too, is not failure. That’s “not learning”. The not learning is a result of something, and that something should be pursued until you learn its name and address. And once named, made to go away.

When the proposed plan is reviewed and improved before it’s carried out, that’s not failure. That’s good process that creates good learning. If the plan is not reviewed, executed well and generates results less than anticipated, it’s not failure. You learned your process needs to change. Now it’s time to improve it.

When a good plan is executed poorly, there is no failure. You learned that one of your teams executed in a way that was different than your expectations. It’s time to learn why it went down as it did and why your expectations were the way they were. Learning on all fronts, failing on none.

Nothing good can come of using the f word, so don’t use it. Use “learn” instead. Don’t embrace failure, embrace learning. Don’t fail early and often, learn early and often. Don’t fail forward (whatever that is), just learn.

With failure there is fear of repercussion and a puckering on all fronts. With learning there is openness and opportunity. You choose the words, so choose wisely.

Image credit – IZATRINI.com

Put your success behind you.

The biggest blocker of company growth is your successful business model. And the more significant it’s historical success, the more it blocks.

Novelty meaningful to the customer is the life force of company growth. The easiest novelty to understand is novelty of product function. In a no-to-yes way, the old product couldn’t do it, but the new one can. And the amount of seconds it takes for the customer to notice (and in the case of meaningful novelty, appreciate) the novelty is in an indication of its significance. If it takes three months of using the product, rigorous data collection and a t-test, that’s not good. If the customer turns on the product and the novelty smashes him in the forehead like a sledgehammer, well, that’s better.

It’s difficult to create a product with meaningful novelty. Engineers know what they know, marketers know what they market, and the salesforce knows how to sell what they sell. And novelty cuts across their comfort. The technology is slightly different, the marketing message diverges a bit, and the sales argument must be modified. The novelty is driven by the product and the people respond accordingly. And, the new product builds on the old one so there’s familiarity.

Where injecting novelty into the product is a challenge, rubbing novelty on the business model provokes a level 5 pucker. Nothing has the stopping power of a proposed change to the business model. Novelty in the product is to novelty in the business model as lightning is to lightning bug – they share a word, but that’s it.

Novelty in the product is novelty of sheet metal, printed circuit boards and software. Novelty in the business model is novelty in how people do their work and novelty in personal relationships. Novelty in the product banal, novelty in the business model is personal.

No tools or best practices can loosen the pucker generated by novelty in the business model. The tired business model has been the backplane of success for longer than anyone can remember. The long-in-the-tooth model has worn deep ruts of success into the organization. Even the all-powerful Lean Startup methodology can’t save you.

The healing must start with an open discussion about the impermanence of all things, including the business model. The most enduring radioactive element has a half-life, and so does the venerable business model, even the most successful.

Where novelty in the product is technical, novelty in the business model is emotional. And that’s what makes it so powerful. Sprinkling the business model with novelty is scary at a deeply personal level – career jeopardy, mortgage insecurity and family volatility are primal drivers. But if you can push through, the rewards are magical.

Your business model has shaped you into an organization that’s optimized to do what it does. You can’t create new markets and sell to new products to new customers without changing your business model. Your business model may have been your secret sauce, but the world’s tastes have changed. It’s time to put your success behind you.

Image credit — MandaRose

Accountability is not the answer.

People have a natural bias toward doing what was done last time. The behavior is the result of untold generations that evolved to serve a single objective – to survive. Survival is about holding onto what is – protecting the family, providing food and waking up the next morning. In survival mode any energy spent on activities even partially unrelated to food, water and shelter is wasted energy. Any deviation from the worn path creates newness and uncertainty which causes adrenaline to flow and increases caloric burn rate. In survival mode the opportunity cost of those extra calories is larger than the potential benefit of a new experience.

People have a natural bias toward doing what was done last time. The behavior is the result of untold generations that evolved to serve a single objective – to survive. Survival is about holding onto what is – protecting the family, providing food and waking up the next morning. In survival mode any energy spent on activities even partially unrelated to food, water and shelter is wasted energy. Any deviation from the worn path creates newness and uncertainty which causes adrenaline to flow and increases caloric burn rate. In survival mode the opportunity cost of those extra calories is larger than the potential benefit of a new experience.

Today, calories are readily available for most and survival is no longer the objective, yet the bias persists. Today, the bias is not driven by a culture of survivability. It’s driven by a culture of accountability. Accountability forces its own singular focus – make the numbers – and, like survivability, tightly links the consequences of mistakes and shortcomings to the individual. Spend your calories any way you want just don’t miss the numbers.

In a culture of accountability there is no time to rest and recharge. Like the predator that never sleeps, metrics continually keep a hungry eye on the human prey. And like with food and water, any deviation from the worn path of increased throughput and profit is unsafe behavior.

But when the watering hole dries up and the fruit has been picked from the trees, the worn path isn’t the safest path. Frantic foraging is the only real option, but it’s not much safer and certainly no way to go through life. Paradoxically, a culture of accountability, with its intent of reducing the risk of missing the numbers can create far more dangerous failure modes. Where over fishing depletes the fish population and over farming makes for a dust bowl, over reliance on what worked last time can create failure modes that jeopardize survival.

To break the bias and help people do new things, measure new things and talk about new things. Start the next meeting with a review of what’s different. The team will feel energized. And after the discussion, adjourn the meeting because everything else is the same. At the next status meeting, talk only about the surprising insights. With the next email, send praise about the new learning. At team meetings, acknowledge the inherent uncertainty of doing new things and praise it over the potentially catastrophic consequences of over extending the tried-and-true. And for metrics, stop measuring outcomes.

Image credit — Applied Nomadology

There is no control. There is only trust.

Control strategies don’t work, but trust strategies do.

Control strategies don’t work, but trust strategies do.

Nothing goes as planned. Trying to control things tightly is wasteful. It takes too much energy to batten down all the hatches and keep them that way every-day-all-day. Maybe no water gets in, but the crew doesn’t get enough oxygen and their brains wither.

Trust on the other hand, is flexible and far more efficient. It takes little energy to hire a pro, give them the right task and get out of the way. And with the best pros it requires even less energy because the three-step becomes a two-step – hire them and get out of the way.

When both hands are continuously busy pulling the levers of contingency plans there are no hands left to point toward the future. When both arms are clinging onto the artificial schedule of the project plan there are no arms left to conduct the orchestra. Control strategies make sure even the piccolo plays the right notes at the right time, while trust strategies let the violins adjust based on their ear and intuition and even let the conductors write their own sheet music.

Control is an illusion, but trust is real. The best statistical analyses are rearward-looking and provide no control in a changing environment. (You can’t drive a car by looking in the rear view mirror.) Yet, that’s the state-of-the-art for control strategies – don’t change the inputs, don’t change the process and we’ll get what we got last time. That’s not control. That’s self-limiting.

Trust is real because people and their relationships are real. Trust is a contract between people where one side expects hard work and good judgment and the other side expects to be challenged and to be given the flexibility to do the work as they see fit. Trust-based systems are far more adaptable than if-then control strategies. No control algorithm can effectively handle unanticipated changes in input conditions or unplanned drift in decision criteria, but people and their judgement can. In fact, that’s what people are good at, and they enjoy doing it. And that’s a great recipe for an engaged work force.

Control strategies are popular because they help us believe we have control. And they’re ineffective for the same reason. Trust strategies are not popular because they acknowledge we have no real control and rely on judgment. And that’s why they’re effective.

When control strategies fail, trust strategies are implemented to save the day. When the wheels fall off a project, the best pro in the company is brought in to fix what’s broken. And the best pro is the most trusted pro. And their charge – Tell us what’s wrong (Use your judgement.), tell us how you’re going to fix it (Use your best judgement for that.) and tell us what you need to fix it. (And use your best judgement for that, too.)

In the end, trust trumps control. But only after all other possibilities are exhausted.

Image credit – Dobi.

Hands-On or Hands-Off?

Hands-on versus hands-off – as a leader it’s a fundamental choice. And for me the single most important guiding principle is – do what it takes to maintain or strengthen the team’s personal ownership of the work.

Hands-on versus hands-off – as a leader it’s a fundamental choice. And for me the single most important guiding principle is – do what it takes to maintain or strengthen the team’s personal ownership of the work.

If things are going well, keep your hands off. This reinforces the team’s ownership and your trust in them. But it’s not hands-off in and ignore them sense; it’s hands-off in a don’t tell them what to do sense. Walk around, touch base and check in to show interest in the work and avoid interrogation-based methods that undermine your confidence in them. This is not to say a hands-off leader only superficially knows what’s going on, it should only look like the leader has a superficial understanding.

The hands-off approach requires a deep understanding of the work and the people doing it. The hands-off leader must make the time to know the GPS coordinates of the project and then do reconnaissance work to identify the positions of the quagmires and quicksand that lay ahead. The hands-off leader waits patiently just in front of the obstacles and makes no course correction if the team can successfully navigate the gauntlet. But when the team is about to sink to their waists, leader gently nudges so they skirt the dangerous territory.

Unless, of course, the team needs some learning. And in that case, the leader lets the team march it’s project into the mud. If they need just a bit of learning the leader lets them get a little muddy; and if the team needs deep learning, the leader lets them sink to their necks. Either way, the leader is waiting under cover as they approach the impending snafu and is right beside them to pull them out. But to the team, the hands-off leader is not out in front scouting the new territory. To them, the hands-off leader doesn’t pay all that much attention. To the team, it’s just a coincidence the leader happens to attend the project meeting at a pivotal time and they don’t even recognize when the leader subtly plants the idea that lets the team pull themselves out of the mud.

If after three or four near-drowning incidents the team does not learn or change it’s behavior, it’s time for the hands-off approach to look and feel more hands-on. The leader calls a special meeting where the team presents the status of the project and grounds the project in the now. Then, with everyone on the same page the leader facilitates a process where the next bit of work is defined in excruciating detail. What is the next learning objective? What is the test plan? What will be measured? How will it be measured? How will the data be presented? If the tests go as planned, what will you know? What won’t you know? How will you use the knowledge to inform the next experiments? When will we get together to review the test results and your go-forward recommendations?

By intent, this tightening down does not go unnoticed. The next bit of work is well defined and everyone is clear how and when the work will be completed and when the team will report back with the results. The leader reverts back to hands-off until the band gets back together to review the results where it’s back to hands-on. It’s the leader’s judgement on how many rounds of hands-on roulette the team needs, but the fun continues until the team’s behavior changes or the project ends in success.

For me, leadership is always hands-on, but it’s hands-on that looks like hands-off. This way the team gets the right guidance and maintains ownership. And as long as things are going well this is a good way to go. But sometimes the team needs to know you are right there in the trenches with them, and then it’s time for hands-on to look like hands-on. Either way, its vital the team knows they own the project.

There are no schools that teach this. The only way to learn is to jump in with both feet and take an active role in the most important projects.

Image credit – Kerri Lee Smith

A Life Boat in the Sea of Uncertainty

Work is never perfect, family life is never perfect and neither is the interaction between them. Regardless of your expectations or control strategies, things go as they go. That’s just what they do.

Work is never perfect, family life is never perfect and neither is the interaction between them. Regardless of your expectations or control strategies, things go as they go. That’s just what they do.

We have far less control than we think. In the pure domain of physics the equations govern predictively – perturb the system with a known input in a controlled way and the output is predictable. When the process is followed, the experimental results repeat, and that’s the acid test. From a control standpoint this is as good as it gets. But even this level of control is more limited than it appears.

Physical laws have bounded applicability – change the inputs a little and the equation may not apply in the same way, if at all. Same goes for the environment. What at the surface looks controllable and predictable, may not be. When the inputs change, all bets are off – the experimental results from one test condition may not be predictive in another, even for the simplest systems, In the cold, unemotional world of physical principles, prediction requires judgement, even in lab conditions.

The domains of business and life are nothing like controlled lab conditions. And they’re and not governed by physical laws. These domains are a collection of complex people systems which are governed by emotional laws. Where physics systems delivers predictable outputs for known inputs, people systems do not. Scenario 1. Your group’s best performer is overworked, tired, and hasn’t exercised in four weeks. With no warning you ask them to take on an urgent and important task for the CEO. Scenario 2. Your group’s best performer has a reasonable workload (and even a little discretionary time), is well rested and maintains a regular exercise schedule, and you ask for the same deliverable in the same way. The inputs are the same (the urgent request for the CEO), the outputs are far different.

At the level of the individual – the building block level – people systems are complex and adaptive, The first time you ask a person to do a task, their response is unpredictable. The next day, when you ask them to do a different task, they adapt their response based on yesterday’s request-response interaction, which results in a thicker layer of unpredictability. Like pushing on a bag of water, their response is squishy and it’s difficult to capture the nuance of the interaction. And it’s worse because it takes a while for them to dampen the reactionary waves within them.

One person interacts with another and groups react to other groups. Push on them and there’s really no telling how things will go. One cylo competes with another for shared resources and complexity is further confounded. The culture of a customer smashes against your standard operating procedures and the seismic pressure changes the already unpredictable transfer functions of both companies. And what about the customer that’s also your competitor? And what about the big customer you both share? Can you really predict how things will go? Do you really have control?

What does all this complexity, ambiguity, unpredictability and general lack of control mean when you’re trying to build a culture of accountability? If people are accountable for executing well, that’s fine. But if they’re held accountable for the results of those actions, they will fail and your culture of accountability will turn into a culture of avoiding responsibility and finding another place to work.

People know uncertainty is always part of the equation, and they know it results in unpredictability. And when you demand predictability in a system that’s uncertain by it’s nature, as a leader you lose credibility and trust.

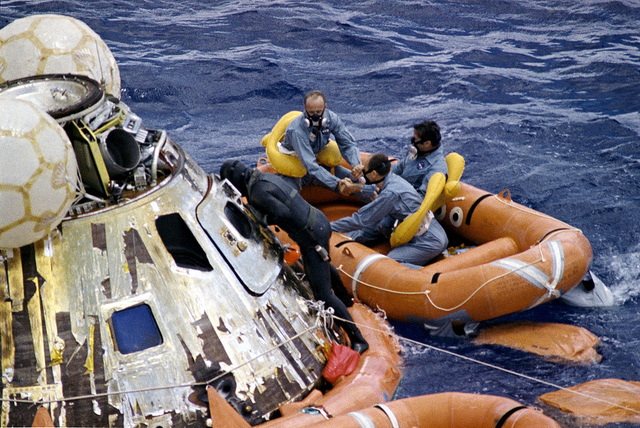

As we swim together in the storm of complexity, trust is the life boat. Trust brings people together and makes it easier to row in the same direction. And after a hard day of mistakenly rowing in the wrong direction, trust helps everyone get back in the boat the next day and pull hard in the new direction you point them.

Image credit – NASA

Out of Context

“It’s a fact.” is a powerful statement. It’s far stronger than a simple description of what happened. It doesn’t stop at describing a sequence of events that occurred in the past, rather it tacks on an implication of what to think about those events. When “it’s a fact” there’s objective evidence to justify one way of thinking over another. No one can deny what happened, no one can deny there’s only one way to see things and no one can deny there’s only one way to think. When it’s a fact, it’s indisputable.

“It’s a fact.” is a powerful statement. It’s far stronger than a simple description of what happened. It doesn’t stop at describing a sequence of events that occurred in the past, rather it tacks on an implication of what to think about those events. When “it’s a fact” there’s objective evidence to justify one way of thinking over another. No one can deny what happened, no one can deny there’s only one way to see things and no one can deny there’s only one way to think. When it’s a fact, it’s indisputable.

Facts aren’t indisputable, they’re contextual. Even when an event happens right in front of two people, they don’t see it the same way. There are actually two events that occurred – one for each viewer. Two viewers, two viewing angles, two contexts, two facts. Right at the birth of the event there are multiple interpretations of what happened. Everyone has their own indisputable fact, and then, as time passes, the indisputables diverge.

On their own there’s no problem with multiple diverging paths of indisputable facts. The problem arises when we use indisputable facts of the past to predict the future. Cause and effect are not transferrable from one context to another, even if based on indisputable facts. The physics of the past (in the true sense of physics) are the same as the physics of today, but the emotional, political, organizational and cultural physics are different. And these differences make for different contexts. When the governing dynamics of the past are assumed to be applicable today, it’s easy to assume the indisputable facts of today are the same as yesterday. Our static view of the world is the underlying problem, and it’s an invisible problem.

We don’t naturally question if the context is different. Mostly, we assume contexts are the same and mostly we’re blind to those assumptions. What if we went the other way and assumed contexts are always different? What would it feel like to live in a culture that always questions the context around the facts? Maybe it would be healthy to justify why the learning from one situation applies to another.

As the pace of change accelerates, it’s more likely today’s context is different and yesterday’s no longer applies. Whether we want to or not, we’ll have to get better at letting go of indisputable facts. Instead of assuming things are the same, it’s time to look for what’s different.

Image credit — Joris Leermakers

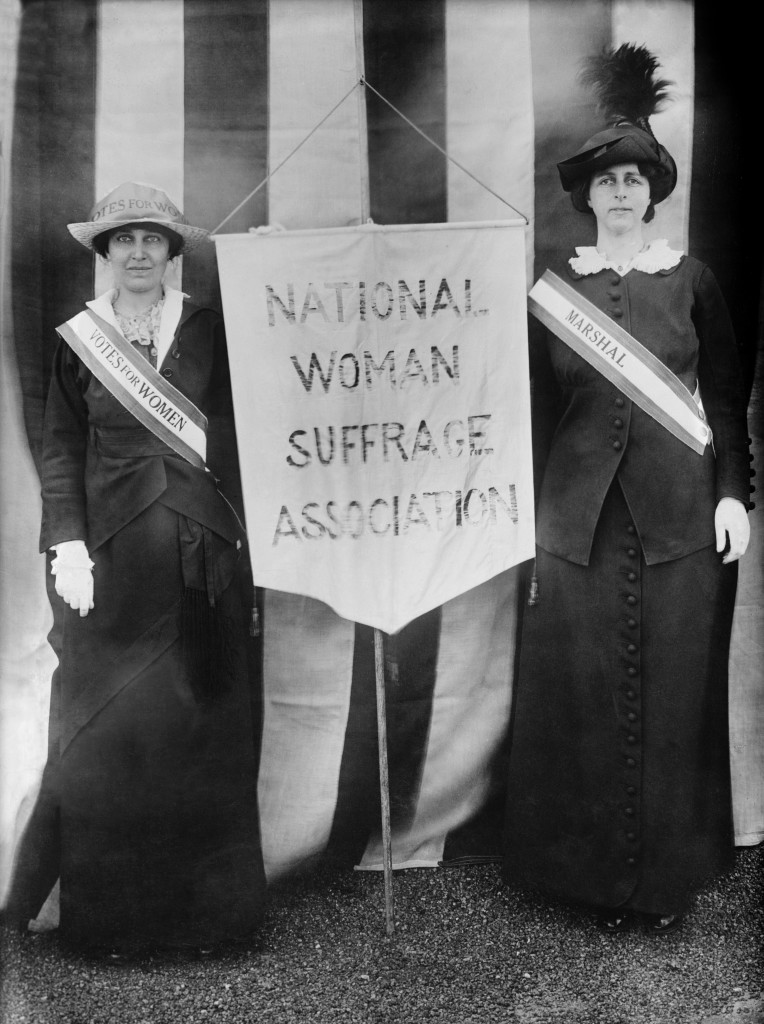

If there’s no conflict, there’s no innovation.

With Innovation, things aren’t always what they seem. And the culprit for all this confusion is how she goes about her work. Innovation starts with different, and that’s the source of all the turmoil she creates.

With Innovation, things aren’t always what they seem. And the culprit for all this confusion is how she goes about her work. Innovation starts with different, and that’s the source of all the turmoil she creates.

For the successful company, Innovation demands the company does things that are different from what made it successful. Where the company wants to do more of the same (but done better), Innovation calls it as she sees it and dismisses the behavior as continuous improvement. Innovation is a big fan of continuous improvement, but she’s a bit particular about the difference between doing things that are different and things that are the same.

The clashing of perspectives and the gnashing of teeth is not a bad thing, in fact it’s good. If Innovation simply rolls over when doing the same is rationalized as doing differently, nothing changes and the recipe for success runs out of gas. Said another way, company success is displaced by company failure. When innovation creates conflict over sameness she’s doing the company favor. Though it sometimes gives her a bad name, she’s willing to put up with the attack on her character.

The sacred business model is a mortal enemy of Innovation. Those two have been getting after each other for a long time now, and, thankfully, Innovation is willing to stand tall against the sacred business model. Innovation knows even the most sacred business models have a half-life, and she knows that she must actively dismantle them as everyone else in the company tries to keep them on life support long after they should have passed. Innovation creates things that are different (novel), useful and successful to help the company through the sad process of letting the sacred business model die with dignity. She’s willing to do the difficult work of bringing to life a younger more viral business model, knowing full well she’s creating controversy and turmoil at every turn. Innovation knows the company needs help admitting the business model is tired and old, and she’s willing to do the hard work of putting it out to pasture. She knows there’s a lot of misplaced attachment to the tired business model, but for the sake of the company, she’s willing to put it out of its misery.

For a long time now the company’s products have delivered the same old value in the same old way to the same old customers, and Innovation knows this. And because she knows that’s not sustainable, she makes a stink by creating different and more profitable value to different and more valuable customers. She uses different assumptions, different technologies and different value propositions so the company can see the same old value proposition as just that – old (and tired). Yes, she knows she’s kicking company leaders in the shins when she creates more value than they can imagine, but she’s doing it for the right reasons. Knowing full well people will talk about her behind her back, she’s willing to create the conflict needed to discredit old value proposition and adopt a new one.

Innovation is doing the company a favor when she creates strife, and the should company learn to see that strife not as disagreement and conflict for their own sake, rather as her willingness to do what it takes to help the company survive in an unknown future. Innovation has been around a long time, and she knows the ropes. Over the centuries she’s learned that the same old thing always runs out of steam. And she knows technologies and their business models are evolving faster than ever. Thankfully, she’s willing to do the difficult work of creating new technologies to fuel the future, even as the status quo attacks her character.

Without Innovation’s disruptive personality there would be far less conflict and consternation, but there’d also be far less change, far less growth and far less company longevity. Yes, innovation takes a strong hand and is sometimes too dismissive of what has been successful, but her intentions are good. Yes, her delivery is sometimes too harsh, but she’s trying to make a point and trying to help the company survive.

Keep an eye out for the turmoil and conflict that Innovation creates, and when you see it fan the flames. And when hear the calls of distress of middle managers capsized by her wake of disruption, feel good that Innovation is alive and well doing the hard work to keep the company afloat.

The time to worry is not when Innovation is creating conflict and consternation at every turn; the time to worry is when the telltale signs of her powerful work are missing.

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski