Archive for the ‘Clarity’ Category

Hands-On or Hands-Off?

Hands-on versus hands-off – as a leader it’s a fundamental choice. And for me the single most important guiding principle is – do what it takes to maintain or strengthen the team’s personal ownership of the work.

Hands-on versus hands-off – as a leader it’s a fundamental choice. And for me the single most important guiding principle is – do what it takes to maintain or strengthen the team’s personal ownership of the work.

If things are going well, keep your hands off. This reinforces the team’s ownership and your trust in them. But it’s not hands-off in and ignore them sense; it’s hands-off in a don’t tell them what to do sense. Walk around, touch base and check in to show interest in the work and avoid interrogation-based methods that undermine your confidence in them. This is not to say a hands-off leader only superficially knows what’s going on, it should only look like the leader has a superficial understanding.

The hands-off approach requires a deep understanding of the work and the people doing it. The hands-off leader must make the time to know the GPS coordinates of the project and then do reconnaissance work to identify the positions of the quagmires and quicksand that lay ahead. The hands-off leader waits patiently just in front of the obstacles and makes no course correction if the team can successfully navigate the gauntlet. But when the team is about to sink to their waists, leader gently nudges so they skirt the dangerous territory.

Unless, of course, the team needs some learning. And in that case, the leader lets the team march it’s project into the mud. If they need just a bit of learning the leader lets them get a little muddy; and if the team needs deep learning, the leader lets them sink to their necks. Either way, the leader is waiting under cover as they approach the impending snafu and is right beside them to pull them out. But to the team, the hands-off leader is not out in front scouting the new territory. To them, the hands-off leader doesn’t pay all that much attention. To the team, it’s just a coincidence the leader happens to attend the project meeting at a pivotal time and they don’t even recognize when the leader subtly plants the idea that lets the team pull themselves out of the mud.

If after three or four near-drowning incidents the team does not learn or change it’s behavior, it’s time for the hands-off approach to look and feel more hands-on. The leader calls a special meeting where the team presents the status of the project and grounds the project in the now. Then, with everyone on the same page the leader facilitates a process where the next bit of work is defined in excruciating detail. What is the next learning objective? What is the test plan? What will be measured? How will it be measured? How will the data be presented? If the tests go as planned, what will you know? What won’t you know? How will you use the knowledge to inform the next experiments? When will we get together to review the test results and your go-forward recommendations?

By intent, this tightening down does not go unnoticed. The next bit of work is well defined and everyone is clear how and when the work will be completed and when the team will report back with the results. The leader reverts back to hands-off until the band gets back together to review the results where it’s back to hands-on. It’s the leader’s judgement on how many rounds of hands-on roulette the team needs, but the fun continues until the team’s behavior changes or the project ends in success.

For me, leadership is always hands-on, but it’s hands-on that looks like hands-off. This way the team gets the right guidance and maintains ownership. And as long as things are going well this is a good way to go. But sometimes the team needs to know you are right there in the trenches with them, and then it’s time for hands-on to look like hands-on. Either way, its vital the team knows they own the project.

There are no schools that teach this. The only way to learn is to jump in with both feet and take an active role in the most important projects.

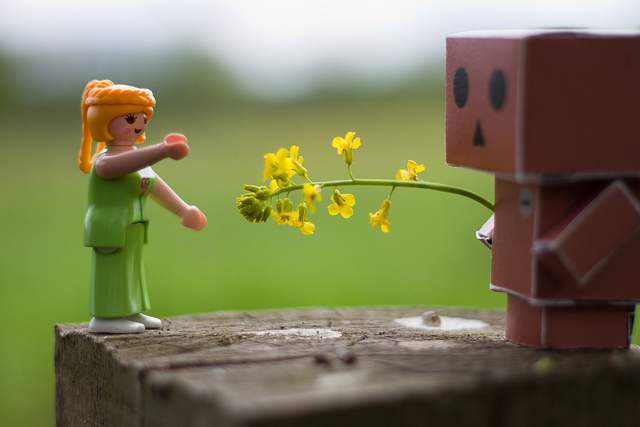

Image credit – Kerri Lee Smith

Out of Context

“It’s a fact.” is a powerful statement. It’s far stronger than a simple description of what happened. It doesn’t stop at describing a sequence of events that occurred in the past, rather it tacks on an implication of what to think about those events. When “it’s a fact” there’s objective evidence to justify one way of thinking over another. No one can deny what happened, no one can deny there’s only one way to see things and no one can deny there’s only one way to think. When it’s a fact, it’s indisputable.

“It’s a fact.” is a powerful statement. It’s far stronger than a simple description of what happened. It doesn’t stop at describing a sequence of events that occurred in the past, rather it tacks on an implication of what to think about those events. When “it’s a fact” there’s objective evidence to justify one way of thinking over another. No one can deny what happened, no one can deny there’s only one way to see things and no one can deny there’s only one way to think. When it’s a fact, it’s indisputable.

Facts aren’t indisputable, they’re contextual. Even when an event happens right in front of two people, they don’t see it the same way. There are actually two events that occurred – one for each viewer. Two viewers, two viewing angles, two contexts, two facts. Right at the birth of the event there are multiple interpretations of what happened. Everyone has their own indisputable fact, and then, as time passes, the indisputables diverge.

On their own there’s no problem with multiple diverging paths of indisputable facts. The problem arises when we use indisputable facts of the past to predict the future. Cause and effect are not transferrable from one context to another, even if based on indisputable facts. The physics of the past (in the true sense of physics) are the same as the physics of today, but the emotional, political, organizational and cultural physics are different. And these differences make for different contexts. When the governing dynamics of the past are assumed to be applicable today, it’s easy to assume the indisputable facts of today are the same as yesterday. Our static view of the world is the underlying problem, and it’s an invisible problem.

We don’t naturally question if the context is different. Mostly, we assume contexts are the same and mostly we’re blind to those assumptions. What if we went the other way and assumed contexts are always different? What would it feel like to live in a culture that always questions the context around the facts? Maybe it would be healthy to justify why the learning from one situation applies to another.

As the pace of change accelerates, it’s more likely today’s context is different and yesterday’s no longer applies. Whether we want to or not, we’ll have to get better at letting go of indisputable facts. Instead of assuming things are the same, it’s time to look for what’s different.

Image credit — Joris Leermakers

Strategic Planning is Dead.

Things are no longer predictable, and it’s time to start behaving that way.

Things are no longer predictable, and it’s time to start behaving that way.

In the olden days (the early 2000s) the pace of change was slow enough that for most the next big thing was the same old thing, just twisted and massaged to look like the next big thing. But that’s not the case today. Today’s pace is exponential, and it’s time to behave that way. The next big thing has yet to be imagined, but with unimaginable computing power, smart phones, sensors on everything and a couple billion new innovators joining the web, it should be available on Alibaba and Amazon a week from next Thursday. And in three weeks, you’ll be able to buy a 3D printer for $199 and go into business making the next big thing out of your garage. Or, you can grasp tightly onto your success and ride it into the ground.

To move things forward, the first thing to do is to blow up the strategic planning process and sweep the pieces into the trash bin of a bygone era. And, the next thing to do is make sure the scythe of continuous improvement is busy cutting waste out of the manufacturing process so it cannot be misapplied to the process of re-imagining the strategic planning process. (Contrary to believe, fundamental problems of ineffectiveness cannot be solved with waste reduction.)

First, the process must be renamed. I’m not sure what to call it, but I am sure it should not have “planning” in the name – the rate of change is too steep for planning. “Strategic adapting” is a better name, but the actual behavior is more akin to probe, sense, respond. The logical question then – what to probe?

[First, for the risk minimization community, probing is not looking back at the problems of the past and mitigating risks that no longer apply.]

Probing is forward looking, and it’s most valuable to probe (purposefully investigate) fertile territory. And the most fertile ground is defined by your success. Here’s why. Though the future cannot be predicted, what can be predicted is your most profitable business will attract the most attention from the billion, or so, new innovators looking to disrupt things. They will probe your business model and take it apart piece-by-piece, so that’s exactly what you must do. You must probe-sense-respond until you obsolete your best work. If that’s uncomfortable, it should be. What should be more uncomfortable is the certainty that your cash cow will be dismantled. If someone will do it, it might as well be you that does it on your own terms.

Over the next year the most important work you can do is to create the new technology that will cause your most profitable business to collapse under its own weight. It doesn’t matter what you call it – strategic planning, strategic adapting, securing the future profitability of the company – what matters is you do it.

Today’s biggest risk is our blindness to the immense risk of keeping things as they are. Everything changes, everything’s impermanent – especially the things that create huge profits. Your most profitable businesses are magnates to the iron filings of disruption. And it’s best to behave that way.

Image credit – woodleywonderworks

Clarity is King

It all starts and ends with clarity. There’s not much to it, really. You strip away all the talk and get right to the work you’re actually doing. Not the work you should do, want to do, or could do. The only thing that matters is the work you are doing right now. And when you get down to it, it’s a short list.

It all starts and ends with clarity. There’s not much to it, really. You strip away all the talk and get right to the work you’re actually doing. Not the work you should do, want to do, or could do. The only thing that matters is the work you are doing right now. And when you get down to it, it’s a short list.

There’s a strong desire to claim there’s a ton of projects happening all at once, but projects aren’t like that. Projects happen serially. Start one, finish one is the best way. Sure it’s sexy to talk about doing projects in parallel, but when the rubber meets the road, it’s “one at time” until you’re done.

The thing to remember about projects is there’s no partial credit. If a project is half done, the realized value is zero, and if a project is 95% done, the realized value is still zero (but a bit more frustrating). But to rationalize that we’ve been working hard and that should count for something, we allocate partial credit where credit isn’t due. This binary thinking may be cold, but it’s on-the-mark. If your new product is 90% done, you can’t sell it – there is no realized value. Right up until it’s launched it’s work in process inventory that has a short shelf like – kind of like ripe tomatoes you can’t sell. If your competitor launches a winner, your yet-to-see-day light product over-ripens.

Get a pencil and paper and make the list of the active projects that are fully staffed, the ones that, come hell or high water, you’re going to deliver. Short list, isn’t it? Those are the projects you track and report on regularly. That’s clarity. And don’t talk about the project you’re not yet working on because that’s clarity, too.

Are those the right projects? You can slice them, categorize them, and estimate the profits, but with such a short list, you don’t need to. Because there are only a few active projects, all you have to do is look at the list and decide if they fit with company expectations. If you have the right projects, it will be clear. If you don’t, that will be clear as well. Nothing fancy – a list of projects and a decision if the list is good enough. Clarity.

How will you know when the projects are done? That’s easy – when the resources start work on the next project. Usually we think the project ends when the product launches, but that’s not how projects are. After the launch there’s a huge amount of work to finish the stuff that wasn’t done and to fix the stuff that was done wrong. For some reason, we don’t want to admit that, so we hide it. For clarity’s sake, the project doesn’t end until the resources start full-time work on the next project.

How will you know if the project was successful? Before the project starts, define the launch date and using that launch data, set a monthly profit target. Don’t use units sold, units shipped, or some other anti-clarity metric, use profit. And profit is defined by the amount of money received from the customer minus the cost to make the product. If the project launches late, the profit targets don’t move with it. And if the customer doesn’t pay, there’s no profit. The money is in the bank, or it isn’t. Clarity.

Clarity is good for everyone, but we don’t behave that way. For some reason, we want to claim we’re doing more work than we actually are which results in mis-set expectations. We all know it’s matter of time before the truth comes out, so why not be clear? With clarity from the start, company leaders will be upset sooner rather than later and will have enough time to remedy the situation.

Be clear with yourself that you’re highly capable and that you know your work better than anyone. And be clear with others about what you’re working on and what you’re not. Be clear about your test results and the problems you know about (and acknowledge there are likely some you don’t know about).

I think it all comes down to confidence and self-worth. Have the courage wear clarity like a badge of honor. You and your work are worth it.

Image credit – Greg Foster

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski