Archive for the ‘Clarity’ Category

The Power of the Reverse Schedule

When planning a project, we usually start with a traditional left-to-right schedule. On the left is the project’s start date, where tasks are added sequentially rightward toward completion. When all the tasks are added and the precedence relationships shift tasks rightward, the completion date becomes known. No one likes the completion date, but it is what it is until we’re asked to pull it in.

When planning a project, we usually start with a traditional left-to-right schedule. On the left is the project’s start date, where tasks are added sequentially rightward toward completion. When all the tasks are added and the precedence relationships shift tasks rightward, the completion date becomes known. No one likes the completion date, but it is what it is until we’re asked to pull it in.

I propose a different approach – a reverse schedule. Instead of left to right, the reverse schedule moves right to left. It starts with the completion date on the right and stacks tasks backward in time toward today. The start date emerges when all the tasks are added and precedence relationships work their magic. Where the traditional schedule tells us when the project will finish, the reverse schedule tells us when we should start. And, usually, the reverse schedule says we should have started several months ago and the project is already late.

There are some subtle benefits of the reverse schedule. It’s difficult to game the schedule and reduce task duration to achieve a desired start date because the tasks are stacked backward in time. (Don’t believe me? Give it a try and you’ll see.) And because the task duration is respectful of the actual work content, the reverse schedule is more realistic. And when there’s too much work in a reverse schedule, the tasks push their way into the past and no one can suggest we should go back in time and start the project three months ago. And since the end date is fixed, we are forced to acknowledge there’s not enough time to do all the work. The beauty of the reverse schedule is it can tell us the project is late BEFORE we start the project.

Here’s a rule: You want to know you’re late before it’s too late.

The real power of the reverse schedule is that it creates a sense of urgency around starting the project. In the project planning phase, a delay of a week here and there is no big deal. But, when the start date slips a day, the completion date slips a day. The reverse schedule clarifies the day-for-day slip and helps the resources move the project sooner so the project can start sooner. And those of us who run projects for a living know this is a big deal. What would you pay for an extra two weeks at the end of a project that’s two weeks behind schedule? Well, if you started two weeks sooner, you wouldn’t need the extra time.

The project doesn’t start when the project schedule says it starts. The project starts when the resources start working on the project in a full-time way. The reverse schedule can create the sense of urgency needed to get the critical resources moved to the project so they can start the work on time.

Image credit — Steve Higgins

It’s time for the art of the possible.

Tariffs. Economic uncertainty. Geopolitical turmoil. There’s no time for elegance. It’s time for the art of the possible.

Tariffs. Economic uncertainty. Geopolitical turmoil. There’s no time for elegance. It’s time for the art of the possible.

Give your sales team a reason to talk to customers. Create something that your salespeople can talk about with customers. A mildly modified product offering, a new bundling of existing products, a brochure for an upcoming new product, a price reduction, a program to keep prices as they are even though tariffs are hitting you. Give them a chance to talk about something new so the customers can buy something (old or new).

Think Least Launchable Unit (LLU). Instead of a platform launch that can take years to develop and commercialize, go the other way. What’s the minimum novelty you can launch? What will take the least work to launch the smallest chunk of new value? Whatever that is, launch it now.

Take a Frankensteinian approach. Frankenstein’s monster was a mix and match of what the good doctor had scattered about his lab. The head was too big, but it was the head he had. And he stitched onto the neck most crudely with the tools he had at his disposal. The head was too big, but no one could argue that the monster didn’t have a head. And, yes, the stitching was ugly, but the head remained firmly attached to the neck. Not many were fans of the monster, but everyone knew he was novel. And he was certainly something a sales team could talk about with customers. How can you combine the head from product A with the body of product B? How can you quickly stitch them together and sell your new monster?

Less-With-Far-Less. You’ve already exhausted the more-with-more design space. And there’s no time for the technical work to add more. It’s time for less. Pull out some functionality and lots of cost. Make your machines do less and reduce the price. Simplify your offering and make things easier for your customers. Removing, eliminating, and simplifying usually comes with little technical risk. Turning things down is far easier than turning them up. You’ll be pleasantly surprised how excited your customers will be when you offer them slightly less functionality for far less money.

These are trying times, but they’re not to be wasted. The pressure we’re all under can open us up to do new work in new ways. Push the envelope. Propose new offerings that are inelegant but take advantage of the new sense of urgency forced.

Be bold and be fast.

Image credit — Geoff Henson

Bringing Your Whole Self To The Party

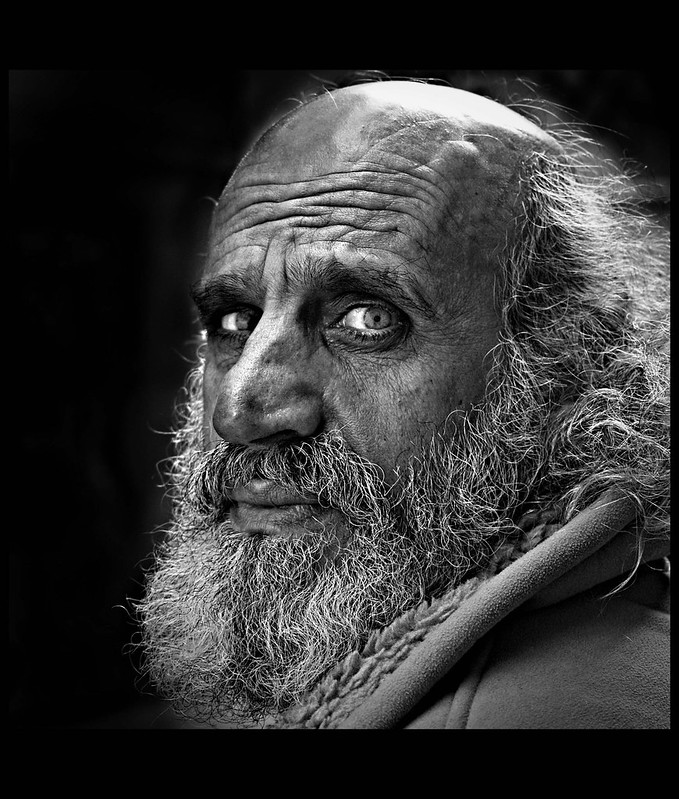

If it’s taken from you, you’ll have a problem if you think it was yours.

If it’s taken from you, you’ll have a problem if you think it was yours.

When it’s taken from you, it doesn’t matter if it was never yours.

No one can take anything from you unless you think it is yours.

There can be no loss if it was never yours to have.

You can be manipulated if they know you have a problem letting go.

Said differently, if you can let go you can’t be manipulated.

Whether you want to admit it or not, it all goes away.

But if you see your favorite mug as already broken, there’s no problem when it breaks.

If you recognize your thirties will end, you won’t feel slighted when you start your fourth decade.

And it’s the same when you start your your fifth.

When you know things will end, their ending comes easier.

When you’re aware it will end, you can do it your way.

When you’re aware it’s finite, it’s easier to do what you think is right.

When you’re it all goes away, you can better appreciate what you have.

When you’re aware everything has a half-life, you’re less likely to live your life as a half-person.

Wouldn’t you like to do things your way?

Wouldn’t you like to do what you think is right?

Wouldn’t you like to live as a whole person?

Wouldn’t you like to appreciate what you have?

Would’t you like to bring your whole self to the party?

If so, why not embrace the impermanence?

Image credit — 正面顔〜〜〜(- .. -)

It’s not about failing fast; it’s about learning fast.

No one has ever been promoted by failing fast. They may have been promoted because they learned something important from an experiment that delivered unexpected results, but that’s fundamentally different than failure. That’s learning.

Failure, as a word, has the strongest negative connotations. Close your eyes and imagine a failure. Can you imagine a scenario where someone gets praised or promoted for that failure? I think not. It’s bad when you fail to qualify for a race. It’s bad when you fail to get that new job. It’s bad when driving down the highway the transmission fails fast. If you squint, sometimes you can see a twinkle of goodness in failure, but it’s still more than 99% bad.

When it’s bad for people’s careers, they don’t do it. Failure is like that. If you want to motivate people or instill a new behavior, I suggest you choose a word other than failure.

Learning, as a word, has highly positive connotations. Children go to school to learn, and that’s good. People go to college to learn, and that’s good. When people learn new things they can do new things, and that’s good. Learning is the foundation for growth and development, and that’s good.

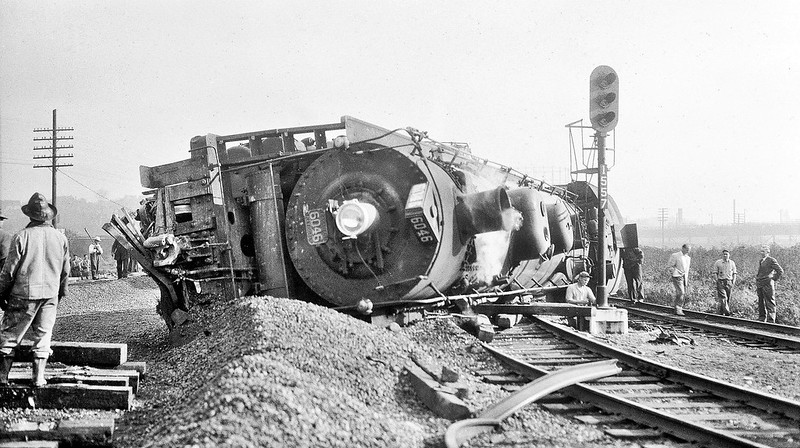

Learning can look like failure to the untrained eye. The prototype blew up – FAILURE. We thought the prototype would survive the test, but it didn’t. We ran a good test, learned the weakest element, and we’re improving it now – LEARNING. In both cases, the prototype is a complete wreck, but in the FAILURE scenario, the team is afraid to talk about it, and in the LEARNING scenario they brag. In the LEARNING scenario, each team member stands two inches taller.

Learning yes; failure no.

The transition from failure to learning starts with a question: What did you learn? It’s a magic question that helps the team see the progress instead of the shattered remains. It helps them see that their hard work has made them smarter. After several what-did-you-learns, the team will start to see what they learned. Without your prompts, they’ll know what they learned. Then, they’ll design their work around their desired learning. Then they’ll define formal learning objectives (LOs). Then they’ll figure out how to improve their learning rate. And then they’re off to the races.

You don’t break things for the sake of breaking them. You break things so you can learn.

Learning yes; failure no. Because language matters.

Image credit — mining camper

Happy, Lonely, Sad, Angry

Happy – when you can bring your whole self to everything you do.

Happy – when you can bring your whole self to everything you do.

Lonely – when you’re with people all day but can’t be truthful with them.

Sad – when you see what could be but never will.

Angry – when someone is less than truthful.

Happy – when people you care about are treated well.

Lonely – when you’re misunderstood.

Sad – when you realize a person’s lack of truthfulness will make them lonely.

Angry – when you take things personally that aren’t personal.

Happy – when an old friend visits.

Lonely – when there’s no trust.

Sad – when you see someone break trust and you know that will bring them loneliness.

Angry – when you know someone should know better.

Happy – when someone asks you for help.

Lonely – when you know you can help but they don’t ask.

Sad – when someone is set up for failure and there’s no way to help them.

Angry – when that someone is a good friend.

Happy – when you have your health.

Happy – when you have fun with friends.

Happy – when you spend time outside.

Happy – when you walk your dogs.

Happy – when your kids and your partner love you.

Whether you’re happy, lonely, sad, or angry, this too shall pass.

Image credit – Tambako the Jaguar.

Wanting What You Have

If you got what you wanted, what would you do?

If you got what you wanted, what would you do?

Would you be happy or would you want something else?

Wanting doesn’t have a half-life. Regardless of how much we have, wanting is always right there with us lurking in the background.

Getting what you want has a half-life. After you get what you want, your happiness decays until what you just got becomes what you always had. I think they call that hedonistic adaptation.

When you have what you always had, you have two options. You can want more or you can want what you have. Which will you choose?

When you get what you want, you become afraid to lose what you got. There’s no free lunch with getting what you want.

When you want more, I can manipulate you. I wouldn’t do that, but I could.

When you want more your mind lives in the future where it tries to get what you want. And lives in the past where it mourns what you did not get or lost.

It’s easier to live in the present moment when you want what you have. There’s no need to craft a plan to get more and no need to lament what you didn’t have.

You can tell when a person wants what they have. They are kind because there’s no need to be otherwise. They are calm because things are good. And they are themselves because they don’t need anything from anyone.

Wanting what you have is straightforward. Whatever you have, you decide that’s what you want. It’s much different than having what you want. Once you have what you want hedonistic adaptation makes you want more, and then it’s time to jump back on the hamster wheel.

Wanting what you have is freeing. Why not choose to be free and choose to want what you have?

Image credit — Steven Guzzardi

Swimming In New Soup

You know the space is new when you don’t have the right words to describe the phenomenon.

You know the space is new when you don’t have the right words to describe the phenomenon.

When there are two opposite sequences of events and you think both are right, you know the space is new.

You know you’re thinking about new things when the harder you try to figure it out the less you know.

You know the space is outside your experience but within your knowledge when you know what to do but you don’t know why.

When you can see the concept in your head but can’t drag it to the whiteboard, you’re swimming in new soup.

When you come back from a walk with a solution to a problem you haven’t yet met, you’re circling new space.

And it’s the same when know what should be but it isn’t – circling new space.

When your old tricks are irrelevant, you’re digging in a new sandbox.

When you come up with a new trick but the audience doesn’t care – new space.

When you know how an experiment will turn out and it turns out you ran an irrational experiment – new space.

When everyone disagrees, the disagreement is a surrogate for the new space.

It’s vital to recognize when you’re swimming in a new space. There is design freedom, new solutions to new problems, growth potential, learning, and excitement. There’s acknowledgment that the old ways won’t cut it. There’s permission to try.

And it’s vital to recognize when you’re squatting in an old space because there’s an acknowledgment that the old ways haven’t cut it. And there’s permission to wander toward a new space.

Image credit — Tambaco The Jaguar

The Frustration Equation

For right frustration to emerge, you need an accurate understanding of how things are, a desire for them to be different, and a recognition you can’t remedy the situation.

For right frustration to emerge, you need an accurate understanding of how things are, a desire for them to be different, and a recognition you can’t remedy the situation.

The emergence of your desire for things to be different starts with knowing how things are. And to see things as they are, you’ve got to be in the right condition – well-rested, unstressed, and sitting in the present moment. When you’re tired, stressed, or sitting in the past or future you can’t pay attention. And when you don’t pay attention, you miss details or context and see something that isn’t. Or, if you’re tired or stressed you can have clear eyes and a muddy interpretation. Either way, you’re off to a bad start because your desire for things to be different is wrongly informed. Sure, your misunderstanding can lead to a desire for things to be different, but your desire is founded on the wrong understanding. If you want your frustration to be right frustration, seeing things as they are is the foundational step. But it’s not yet a desire for things to be different.

Your desire for things to be different is a subtraction of sorts – when how things are minus how you want them to be equals something other than zero. (See Eq. 1) Your brain-body uses that delta to create a desire for things to be different. If how things are is equal to how you want them to be, the difference is zero (no delta) and there is no forcing function for your desire. In that way, if you always want things to be as they are, there can be no desire for difference and frustration cannot emerge. But frustration can emerge if you know how you want things to be and you recognize they’re not that way.

Eq. 1 Forcing Function for Desire (FFD) = (how things are) – (how you want them to be)

There is a more complete variant of the above equation where FFD is non-zero (there’s a difference between how things are and how you want them) yet frustration cannot emerge. It’s called the “I don’t care enough” variant. (See Eq. 2) With this variant, you recognize how things are, you know how you want them to be, but you don’t care enough to be frustrated.

Eq. 2 FFD = [(how things are) – (how you want them to be)] * (Care Factor)

When you don’t care, your Care Factor (CF) = 0. And when the non-zero delta is multiplied by a CF of zero, FFD is zero. This means there is no forcing function for desire and frustration cannot emerge. But this is not a good place to be. Sure, frustration cannot emerge, but when you don’t care there is no forcing function for change. Yes, you see things aren’t as you want, but you go along for the ride and don’t do anything about it. I think that’s sad. And I think that’s bad for business. I’d rather have frustration.

Eq. 2 can be used by Human Resources as an Occom’s Razor of sorts. If someone is frustrated, their CF is non-zero and they care.

Now the third factor required for frustration to emerge – a recognition you can’t do anything about the mismatch between how things are and how you want them. If you don’t recognize you can’t do anything to equalize how things are and how you want them, there can be no frustration. Think – ignorance is bliss. If you think you can do something to make how things are the same as how you want them, there is no frustration. Because it’s important to you (CF is non-zero), you will devote energy to bringing the two sides together and there will be no frustration. But when there’s a mismatch between how things are and how you want them, you care about making that mismatch go away, and you recognize you can’t do anything to eliminate the mismatch, frustration emerges.

What does all this say about people who display frustration? Do you want people that know how to see things as they are? Do you want people who can imagine how things can be different? Do you want people who understand the difference between what they can change and what they cannot? Do you want people who care enough to be frustrated?

Image credit — Atilla Kefeli

Respect what cannot be changed.

If you try to change what you cannot, your trying will not bring about change. But it will bring about 100% frustration, 100% dissatisfaction, 100% missed expectations, 0% progress, and, maybe, 0% employment.

If you try to change what you cannot, your trying will not bring about change. But it will bring about 100% frustration, 100% dissatisfaction, 100% missed expectations, 0% progress, and, maybe, 0% employment.

Here’s a rule: If success demands you must change what you cannot, you will be unsuccessful.

If you try to change something you cannot change but someone else can, you will be unsuccessful unless you ask them for help. That part is clear. But here’s the tricky part – unless you know you cannot change it and they can, you won’t know to ask them.

If you know enough to ask the higher power for help and they say no but you try to change it anyway, you will be unsuccessful. I don’t think that needed to be said, but I thought it important to overcommunicate to keep you safe.

Here’s the money question – How do you know if you can change it?

Here’s another rule: If you want to know if you can change something, ask.

If the knowledgeable people on the project say they cannot change it, believe them. Make a record of the assessment for future escalation, define the consequences, and rescope the project accordingly. Next, search the organization (hint – look north) for someone with more authority and ask them if they can grant the authority to change it. If they say no, document their decision and stick with the rescoped project plan. If they say yes, document their decision and revert to the original project plan.

If you do one thing tomorrow, ask your project team if success demands they change something they cannot. I surely hope their answer is no.

Image credit — zczillinger

Resource Allocation IS Strategy

In business, we have vision statements, mission statements, strategic plans, strategic initiatives, and operating plans. And every day there are there are countless decisions to make. But, in the end, it all comes down to one thing – how we allocate our resources. Whether it’s hiring people, training them, buying capital, or funding projects, all strategic decisions come back to resource allocation. Said more strongly, resource allocation is strategy.

In business, we have vision statements, mission statements, strategic plans, strategic initiatives, and operating plans. And every day there are there are countless decisions to make. But, in the end, it all comes down to one thing – how we allocate our resources. Whether it’s hiring people, training them, buying capital, or funding projects, all strategic decisions come back to resource allocation. Said more strongly, resource allocation is strategy.

Take a look back at last year. Where did you allocate your capital dollars? Which teams got it and which did not? Your capital allocation defined your priorities. The most important businesses got more capital. More to the point – the allocated capital defined their importance. Which projects were fully staffed and fully budgeted? Those that were resourced more heavily were more important to your strategy, which is why they were resourced that way. Which businesses hired people and which did not? The hiring occurred where it fulfilled the strategy. Which teams received most of the training budget? Those teams were strategically important. Prioritization in the form of resource allocation.

Repeat the process for this year’s operating plan. Where is the capital allocated? Where is the hiring allocated? Where are the projects fully staffed and budgeted? Regardless of the mission statements, this year’s strategy is defined by where the resources are allocated. Full stop.

Repeat the process for your forward-looking strategic plans. Where are the resources allocated? Which teams get more? Which get fewer? Answer these questions and you’ll have an operational definition of your company’s forward-looking strategy.

To know if the new strategy is different from the old one, look at the budgets. Do they show a change in resource allocation? Will old projects stop so new ones can start? Do the new projects serve new customers and new value propositions? Same old projects, same old customers, same old value propositions, same old strategy.

To determine if there’s a new strategy, look for changes in capital allocation. If the same teams are allocated more of the same capital, it’s likely the strategy is also the same. Will one team get more capital while the others get less? Well, it’s likely a new strategy is starting to take shape.

Look for a change in hiring. Fewer hires like last year and more of a new flavor probably indicate a change in strategy. And if people flow from one team to another, that’s the same as one team getting new hires and the other team losing them. That type of change in resource allocation is an indicator of a strategic change.

If the resource allocation differs from the strategic plan, believe the resource allocation. And if the resource allocation is the same as last year, so is the strategy. And if there is talk of changing resource allocation but no actual change, then there is no change in strategy.

Image credit – Scouse Smurf

Some Ifs and Thens To Get You Through Your Day

If you didn’t get what you wanted, why not try wanting what you got?

If you didn’t get what you wanted, why not try wanting what you got?

If the timing isn’t right, what can you change so it is right?

If it could get you in trouble, might you be on to something?

If it’s impossible, don’t bother.

If it’s easy, let someone else do it.

If there’s no possibility of bad things, there’s no possibility of magic.

If you need trust but have not yet secured it, declare failure and do something else.

If there is no progress, don’t push. Move the blocking agent out of the way.

If you don’t know where the cost is, you can’t design it out.

If the timing isn’t right, why didn’t you do it sooner?

If the project went flawlessly, you didn’t try to do anything meaningful.

If you know some people won’t like it, isn’t that reason enough to do it?

If it’s almost impossible, give it a go.

If it’s easy, teach someone else to do it.

If you don’t know where the waste is, you can’t get rid of it.

If you don’t need trust, it’s the perfect time to build it.

If you try the hardest thing first and it doesn’t work, at least you avoid wasting time on the easy stuff.

If you don’t know the number of parts in your product, you have too many.

If the product came out perfectly, you took too long.

If you don’t give it a go, how can you know it’s impossible?

If trust is in short supply, supply it.

If it’s easy, do something else.

If forgiveness is so much better than permission, why do we like to do things under the radar?

If bad things didn’t happen, try harder next time.

Image credit — Gabriel Caparó

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski