Archive for the ‘Assumptions’ Category

Own Your Happiness

Own your ideas, not the drama.

Own your ideas, not the drama.

Own your words, not the gossip.

Own your vision, not the dogma.

Own your effort, not the heckling.

Own your vacation, not the email.

Own your behavior, not the strife.

Own your talent, not the cynicism.

Own your deeds, not the rhetoric.

Own your caring, not the criticism.

Own your sincerity, not the hot air.

Own your actions, not the response.

Own your insights, not the rejection.

Own your originality, not the critique.

Own your passion, not the nay saying.

Own your loneliness, not the back story.

Own your health, not the irrational workload.

Own your thinking, not the misunderstanding.

Own your stress level, not the arbitrary due date.

Own your happiness.

How long will it take?

How long will it take? The short answer – same as last time. How long do we want it to take? That’s a different question altogether.

How long will it take? The short answer – same as last time. How long do we want it to take? That’s a different question altogether.

If the last project took a year, so will the next one. Even if you want it to take six months, it will take a year. Unless, there’s a good reason it will be different. (And no, the simple fact you want it to take six months is not a good enough reason in itself.)

Some good reasons it will take longer than last time: more work, more newness, less reuse, more risk, and fewer resources. Some good reasons why it will go faster: less work, less newness, more reuse, less risk, more resources. Seems pretty tight and buttoned-up, but things aren’t that straight forward.

With resources, the core resources are usually under control. It’s the shared resources that are the problem. With resources under their control (core resources) project teams typically do a good job – assign dedicated resources and get out of the way. Shared resources are named that way because they support multiple projects, and this is the problem. Shared resources create coupling among projects, and when one project runs long, resource backlogs ripple through the other projects. And it gets worse. The projects backlogged by the initial ripple splash back and reflect ripples back at each other. Understand the shared resources, and you understand a fundamental dynamic of all your projects.

Plain and simple – work content governs project timelines. And going forward I propose we never again ask “How long will it take?” and instead ask “How is the work content different than last time?” To estimate how long it will take, set up a short face-to-face meeting with the person who did it last time, and ask them how long it will take. Write it down, because that’s the best estimate of how long it will take.

It may be the best estimate, but it may not be a good one. The problem is uncertainty around newness. Two important questions to calibrate uncertainty: 1) How big of a stretch are you asking for? and 2) How much do you know about how you’ll get there? The first question drives focus, but it’s not always a good predictor of uncertainty. Even seemingly small stretches can create huge problems. (A project that requires a 0.01% increase in the speed of light will be a long one.) What matters is if you can get there.

To start, use your best judgment to estimate the uncertainty, but as quickly as you can, put together a rude and crude experimental plan to reduce it. As fast as you can execute the experimental plan, and let the test results tell you if you can get there. If you can’t get there on the bench, you can’t get there, and you should work on a different project until you can.

The best way to understand how long a project will take is to understand the work content. And the most important work content to understand is the new work content. Choose several of your best people and ask them to run fast and focused experiments around the newness. Then, instead of asking them how long it will take, look at the test results and decide for yourself.

Mindset for Doing New

The more work I do with innovation, the more I believe mindset is the most important thing. Here’s what I believe:

The more work I do with innovation, the more I believe mindset is the most important thing. Here’s what I believe:

Doing new doesn’t take a lot of time; it’s getting your mind ready that takes time.

Engineers must get over their fear of doing new.

Without a problem there can be no newness.

Problem definition is the most important part of problem solving.

If you believe it can work or it can’t, you’re right.

Activity is different from progress.

Thinking is progress.

In short, I believe state-of-the-art is limited by state-of-mind.

Impossible

Things aren’t impossible on their own, our thinking makes them so.

Things aren’t impossible on their own, our thinking makes them so.

Impossible is not about the thing itself, it’s a statement about our state of mind.

When we say impossible, we really say we lack confidence to try.

When we say impossible, we really say we are too afraid to try.

The mission of impossible is to shut down all possibility of possibility.

To soften it, we say almost impossible, but it’s the same thing.

When we say impossible, we make a big judgment – but not about the thing – about ourselves.

Less With Far Less

We don’t know the question, but the answer is innovation. And with innovation it’s more, more, more. Whether it’s more with less, or a lot more with a little more, it’s always more. It’s bigger, faster, stronger, or bust. It’s an enhancement of what is, or an extrapolation of what we have. Or it’s the best of product one added to product two. But it’s always more.

We don’t know the question, but the answer is innovation. And with innovation it’s more, more, more. Whether it’s more with less, or a lot more with a little more, it’s always more. It’s bigger, faster, stronger, or bust. It’s an enhancement of what is, or an extrapolation of what we have. Or it’s the best of product one added to product two. But it’s always more.

More-on-more makes radical shifts hard because with more-on-more we hold onto all functionality then add features, or we retain all features then multiply output. This makes it hard to let go of constraints, both the fundamental ones – which we don’t even see as constraints because they masquerade as design rules – and the little-known second class constraints – which we can see, but don’t recognize their power to block first class improvements. (Second class constraints are baggage that come with tangential features which stop us from jumping onto new S-curves for the first class stuff.)

To break the unhealthy cycle of more-on-more addition, think subtraction. Take out features and function. Distill to the essence. Decree guilty until proven innocent, and make your marketers justify the addition of every feature and function. Starting from ground zero, ask your marketers, “If the product does just one thing, what should it do?” Write it down as input to the next step.

Next, instead of more-on-more multiplication, think division. Divide by ten the minimum output of your smallest product. (The intent it to rip your engineers and marketers out of the rut that is your core product line.) With this fractional output, ask what other technologies can enable the functionality? Look down. Look to little technologies, technologies that you could have never considered at full output. Congratulations. You’ve started on your migration toward with less-with-far-less.

On the surface, less-with-far-less doesn’t seem like a big deal. And at first, folks roll their eyes at the idea of taking out features and de-rating output by ten. But its magic is real. When product performance is clipped, constraints fall by the wayside. And when the product must do far less and constraints are dismissed, engineers are pushed away from known technologies toward the unfamiliar and unreasonable. These unfamiliar technologies are unreasonably small and enable functionality with far less real estate and far less inefficiency. The result is radically reduced cost, size, and weight.

Less-with-far-less enables cost reductions so radical, new markets become viable; it makes possible size and weight reductions so radical, new levels of portability open unimaginable markets; it facilitates power reductions so radical, new solar technologies become viable.

The half-life of constraints is long, and the magic from less-with-far-less builds slowly. Before they can let go of what was, engineers must marinate in the notion of less. But when the first connections are made, a cascade of ideas follow and things spin wonderfully out of control. It becomes a frenzy of ideas so exciting, the problem becomes cooling their jets without dampening their spirit.

Less-with-far-less is not dumbed-down work – engineers are pushed to solve new problems with new technologies. Thermal problems are more severe, dimensional variation must be better controlled, and failure modes are new. In fact, less-with-far-less creates steeper learning curves and demands higher-end technologies and even adolescent technologies.

Our thinking, in the form of constraints, limits our thinking. Less-with-far-less creates the scarcity that forces us to abandon our constraints. Less-with-far-less declares our existing technologies unviable and demands new thinking. And I think that’s just what we need.

Beliefs Govern Ideas

Some ideas are so powerful they change you. More precisely, some ideas are so powerful you change your beliefs to fit them.

Some ideas are so powerful they change you. More precisely, some ideas are so powerful you change your beliefs to fit them.

These powerful ideas come in two strains: those that already align with your beliefs and those that contradict.

The first strain works subtly. While you think on the idea, your beliefs test it for safety. (They work in the background without your knowledge.) And if the idea passes the sniff test, and your beliefs feel safe, they let the subconscious sniffing morph into conscious realization – the idea fits your beliefs. The result: You now better understand your beliefs and you blossom, grow, and amplify yourself.

The second strain is subtle as a train wreck – a full frontal assault on your beliefs. This strain contradicts our beliefs and creates an emotional response – fear, anger, stress. And because these ideas threaten our beliefs, our beliefs reject them for safety’s sake. It’s like an autoimmune system for ideas.

But this autoimmune system has a back door. While it rejects most of the idea, for unknown reasons it passes a wisp to our belief system for sniffing. Like a vaccine, it wants to strengthen our beliefs against the strain. And in most cases, it works. But in rare cases, through deep introspection, our beliefs self-mutate and align with the previously contradicting idea. The result: You change yourself fundamentally.

Truth is, ideas are not about ideas; ideas are about beliefs. Our beliefs give life to ideas, or kill them. But we give ideas too much responsibility, and take too little. Truth is, we can change what we think and feel about ideas.

More powerfully, we can change what we think and feel about our beliefs, but only if we believe we can.

Seeing Things As They Are

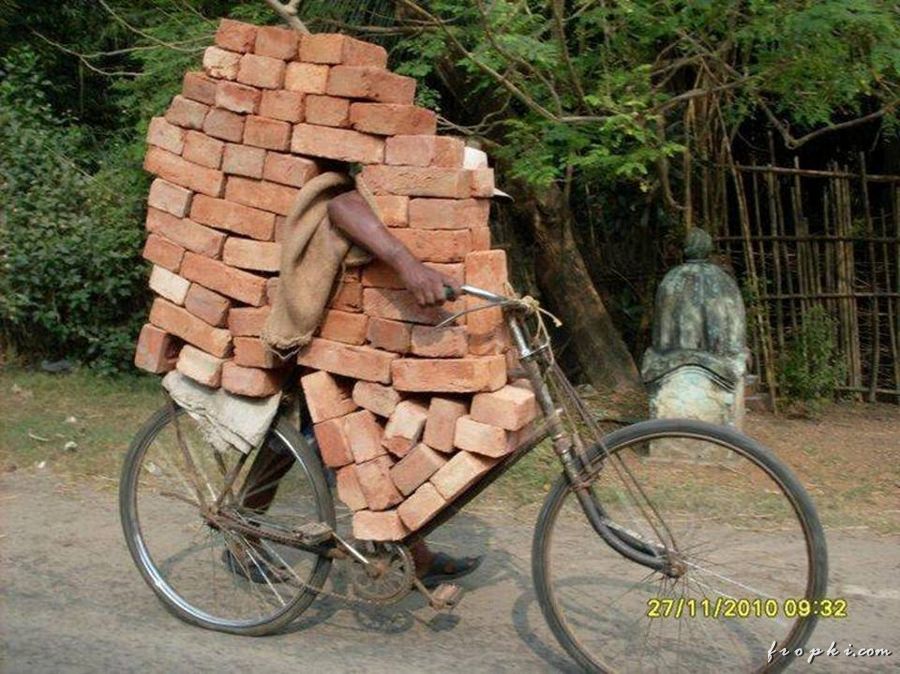

It’s tough out there. Last year we threw the kitchen sink at our processes and improved them, and now last year’s improvements are this year’s baseline. And, more significantly, competition has increased exponentially – there are more eager countries at the manufacturing party. More countries have learned that manufacturing jobs are the bedrock of sustainable economy. They’ve designed country-level strategies and multi-decade investment plans (education, infrastructure, and energy technologies) to go after manufacturing jobs as if their survival depended on them. And they’re not just making, they’re designing and making. Country-level strategies and investments, designing and making, and citizens with immense determination to raise their standard of living – a deadly cocktail. (Have you seen Hyundai’s cars lately?)

It’s tough out there. Last year we threw the kitchen sink at our processes and improved them, and now last year’s improvements are this year’s baseline. And, more significantly, competition has increased exponentially – there are more eager countries at the manufacturing party. More countries have learned that manufacturing jobs are the bedrock of sustainable economy. They’ve designed country-level strategies and multi-decade investment plans (education, infrastructure, and energy technologies) to go after manufacturing jobs as if their survival depended on them. And they’re not just making, they’re designing and making. Country-level strategies and investments, designing and making, and citizens with immense determination to raise their standard of living – a deadly cocktail. (Have you seen Hyundai’s cars lately?)

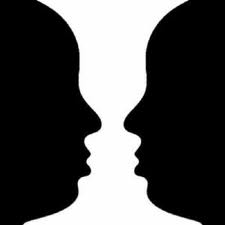

With the wicked couple of competition and profitability goals, we’re under a lot of pressure. And with the pressure comes the danger of seeing things how we want them instead of how they are, like a self-created optical illusion. Here are some likely optical illusion A-B pairs (A – how we want things; B – how they are):

A. Give people more work and more gets done. B. Human output has a physical limit, and once reached less gets done – and spouses get angry. A. Do more projects in parallel to generate more profit. B. Business processes have physical limits, and once reached projects slow and everyone works harder for the same output. A. Add resources to the core project team and more projects get done. B. Add resources to core projects teams and utilization skyrockets for shared resources – waiting time increases for all. A. Use lean in product development (just like in manufacturing) to launch new products better and faster. B. Lean done in product development is absolutely different than in manufacturing, and design engineers don’t take kindly to manufacturing folks telling them how to do their work. A. Through negotiation and price reduction, suppliers can deliver cost reductions year-on-year. B. The profit equation has a physical limit (no profit), and once reached there is no supplier. A. Use lean to reduce product cost by 5%. B. Use DFMA to reduce product cost by 50%.Competition is severe and the pressure is real. And so is the danger to see things as we want them to be. But there’s a simple way to see things as they are: ask the people that do the work. Go to the work and ask the experts. They do the work day-in-day-out, and they know what really happens. They know the details, the pinch points, and the critical interactions.

To see things as they are, check your ego at the door, and go ask the experts – the people that do the work.

I see dead people.

Seeing things as they are takes skill, but doing something about it takes courage. Want an example? Check out movie The Sixth Sense directed by M. Night Shyamalan.

Seeing things as they are takes skill, but doing something about it takes courage. Want an example? Check out movie The Sixth Sense directed by M. Night Shyamalan.

At the start of the film Dr. Malcolm Crowe, esteemed child psychologist, returns home with his wife to find his former patient, Vincent Grey, waiting for him. Grey accuses Crowe of failing him and shoots Crowe in the lower abdomen, then shoots himself.

Cut to a scene three months later where Crowe councils Cole Sear, a troubled, isolated nine year old. Over time, Crowe gains the boy’s trust. The boy ultimately confides in Crow telling him he “Sees dead people that walk around like regular people.” (Talk about seeing things as they are.) Later in the film the boy confides in his mother telling her what he sees. Understandably, his mother does not believe him. But imagine his pain when, after sharing his disturbing reality, his only parent does not support him. (And we get upset when co-workers don’t support our somewhat off-axis realities.) And imagine his courage to move forward.

It takes level 5 courage for him to talk about such a disturbing reality, but Cole Sear is up to the challenge. He so badly wants to change his situation, to shape his future, he does what it takes. Not just talk, but actions. He defines his new future and defines the path to get there. He defines his fears and decides to work through them to create his new future where he is no longer afraid of the dead who seek him out. He changes his go-forward behavior. Instead of hiding, he talks with the dead, understands what they want from him, and helps them. He walks the path.

Ultimately he creates a future that works for him. He convinces his mom that his reality is real; she believes him and supports him and his reality. (That’s what we all want, isn’t it?) His relationships with the dead are non-confrontational and grounded in mutual respect. His stress level is back to mortal levels. His reality is real to people he cares about. But Cole Sear is not done yet.

***** SPOILER ALERT – IF YOU HAVE NOT SEEN THE SIXTH SENSE, READ NO FURTHER ****

In Shyamalan’s classic finish-with-a-twist style, Cole Sear, the scared nine year old boy with his bizarre reality, masterfully convinces his psychologist that his I see dead people reality is real and convinces the psychologist that he’s dead. All along, when the psychologist thought he was helping the boy see things as they are, the boy was helping the psychologist. The little boy who saw dead people convinced the dead psychologist that his seemingly bizarre reality was real.

As Cole demonstrated, seeing things for what they are and doing something about can make a difference in someone’s life.

DoD’s Affordability Eyeball

The DoD wants to do the right thing. Secretary Gates wants to save $20B per year over the next five years and he’s tasked Dr. Ash Carter to get it done. In Carter’s September 14th memo titled: “Better Buying Power: Guidance for Obtaining Greater Efficiency and Productivity in Defense Spending” he writes strongly:

The DoD wants to do the right thing. Secretary Gates wants to save $20B per year over the next five years and he’s tasked Dr. Ash Carter to get it done. In Carter’s September 14th memo titled: “Better Buying Power: Guidance for Obtaining Greater Efficiency and Productivity in Defense Spending” he writes strongly:

…we have a continuing responsibility to procure the critical goods and services our forces need in the years ahead, but we will not have ever-increasing budgets to pay for them.

And, we must

DO MORE WITHOUT MORE.

I like it.

Of the DoD’s $700B yearly spend, $200B is spent on weapons, electronics, fuel, facilities, etc. and $200B on services. Carter lays out themes to reduce both flavors. On services, he plainly states that the DoD must put in place systems and processes. They’re largely missing. On weapons, electronics, etc., he lays out some good themes: rationalization of the portfolio, economical product rates, shorter program timelines, adjusted progress payments, and promotion of competition. I like those. However, his Affordability Mandate misses the mark.

Though his Affordability Mandate is the right idea, it’s steeped in the wrong mindset, steeped in emotional constraints that will limit success. Take a look at his language. He will require an affordability target at program start (Milestone A)

to be treated like a Key Performance Parameter (KPP) such as speed or power – a design parameter not to be sacrificed or comprised without my specific authority.

Implicit in his language is an assumption that performance will decrease with decreasing cost. More than that, he expects to approve cost reductions that actually sacrifice performance. (Only he can approve those.) Sadly, he’s been conditioned to believe it’s impossible to increase performance while decreasing cost. And because he does not believe it, he won’t ask for it, nor get it. I’m sure he’d be pissed if he knew the real deal.

The reality: The stuff he buys is radically over-designed, radically over-complex, and radically cost-bloated. Even without fancy engineering, significant cost reductions are possible. Figure out where the cost is and design it out. And the lower cost, lower complexity designs will work better (fewer things to break and fewer things to hose up in manufacturing). Couple that with strong engineering and improved analytical tools and cost reductions of 50% are likely. (Oh yes, and a nice side benefit of improved performance). That’s right, 50% cost reduction.

Look again at his language. At Milestone B, when a system’s detailed design is begun,

I will require a presentation of a systems engineering tradeoff analysis showing how cost varies as the major design parameters and time to complete are varied. This analysis would allow decisions to be made about how the system could be made less expensive without the loss of important capability.

Even after Milestone A’s batch of sacrificed of capability, at Milestone B he still expects to trade off more capability (albeit the lesser important kind) for cost reduction. Wrong mindset. At Milestone B, when engineers better understand their designs, he should expect another step function increase in performance and another step function decrease of cost. But, since he’s been conditioned to believe otherwise, he won’t ask for it. He’ll be pissed when he realizes what he’s leaving on the table.

For generations, DoD has asked contractors to improve performance without the least consideration of cost. Guess what they got? Exactly what they asked for – ultra-high performance with ultra-ultra-high cost. It’s a target rich environment. And, sadly, DoD has conditioned itself to believe increased performance must come with increased cost.

Carter is a sharp guy. No doubt. Anyone smart enough to reduce nuclear weapons has my admiration. (Thanks, Ash, for that work.) And if he’s smart enough to figure out the missile thing, he’s smart enough to figure out his contractors can increase performance and radically reduces costs at the same time. Just a matter of time.

There are two ways it could go: He could tell contractors how to do it or they could show him how it’s done. I know which one will feel better, but which will be better for business?

Do you know?

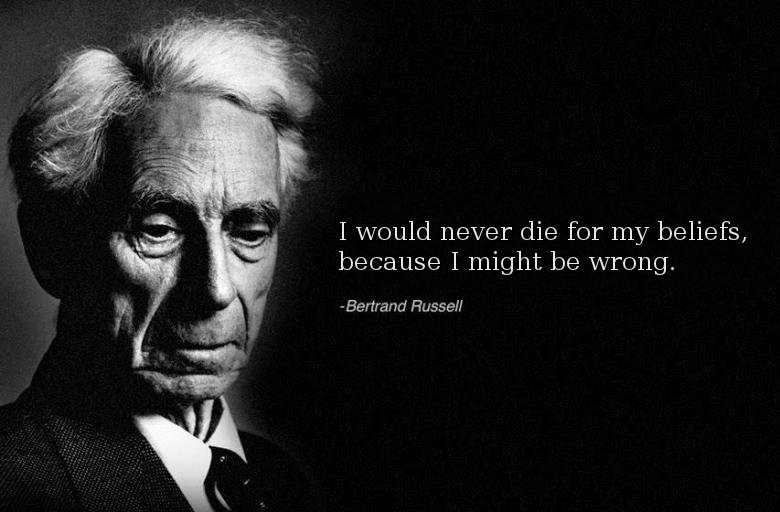

There are three categories of knowing: we know we know, we don’t know, and we think we know.

There are three categories of knowing: we know we know, we don’t know, and we think we know.

When we know we know – we understand fundamentals, we have a model, we have evidence, we can predict. We can build on this knowledge. We’re not often in this state, but it sure feels good when we are. The trick here is to understand the applicability of the knowledge. Change the inputs, change the system, or change the environment and we must question our knowledge. Do the fundamentals still apply?

When we don’t know – no fundamentals, no model, and no predictions. No danger on building on bad knowledge. Life is uncomplicated. Next task: develop the fundamentals; build a model. We’re in this state more often than we admit, and there’s the danger. It’s politically difficult to say “I don’t know.” But it must be said. Otherwise we’re expected to predict the future and to build on the knowledge (that we don’t have).

When we think we know – no fundamentals, no model, and predictions we bet our businesses on. Danger. It feels just as good as when we know we know, but it shouldn’t. Momentum in the wrong direction and we don’t know it. And we’re likely in this state more often than not. But this is a meta-state, an unstable state. The trick is to push on our knowledge so we tip into one of the other two states. Push on our knowledge so we know if we know.

Do you know the fundamentals? Do you have a model? Can you predict?

Blind To Your Own Assumptions

Whether inventing new technologies, designing new products, or solving manufacturing problems, it’s important to understand assumptions. Assumptions shape the technical approach and focus thinking on what is considered (assumed) most important. Blindness to assumptions is all around us and is a real reason for concern. And the kicker, the most dangerous ones are also the most difficult to see – your own assumptions. What techniques or processes can we use to ferret out our own implicit assumptions?

Whether inventing new technologies, designing new products, or solving manufacturing problems, it’s important to understand assumptions. Assumptions shape the technical approach and focus thinking on what is considered (assumed) most important. Blindness to assumptions is all around us and is a real reason for concern. And the kicker, the most dangerous ones are also the most difficult to see – your own assumptions. What techniques or processes can we use to ferret out our own implicit assumptions?

By definition, implicit assumptions are made without formalization, they’re not explicit. Unknowingly, fertile design space can be walled off. Like the archeologist digging on the wrong side of they pyramid, dig all he wants, he won’t find the treasure because it isn’t there. Also with implicit assumptions, precious time and energy can be wasted solving the wrong problem. Like the auto mechanic who replaced the wrong part, the real problem remains. Both scenarios can create severe consequences for a product development project. (NOTE: the notion of implicit assumptions is closely related to the notion of intellectual inertia. See Categories – Intellectual Inertia for a detailed treatment.)

Now the tough part. How to identify your own implicit assumptions? When at their best, the halves of our brains play nicely together, but never does either side rise to the level of omnipotence. It’s impossible to stand outside ourselves and watch us make implicit assumptions. We don’t work that way. We need some techniques.

Narrow, narrow, narrow. The probability of making implicit assumptions decreases when the conflict domain is narrowed.

Narrow in space and time to make the conflict domain small and assumptions are reduced.

Narrow the conflict domain in space – narrow to two elements of the design that aren’t getting along. Not three elements – that’s one too many, but two. Narrow further and make sure the two conflicting elements are in direct physical contact, with nothing in between. Narrow further and define where they touch. Get small, really small, so small the direct contact is all you see. Narrowing in space reduces space-based assumptions.

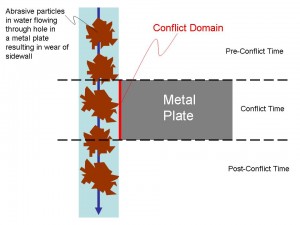

Narrow the conflict domain in time – break it into three time domains: pre-conflict time, conflict time, post-conflict time. This is a foreign idea, but a powerful one. Solutions are different in the three time domains. The conflict can be prevented before it happens in the pre-conflict time, conflict can be dealt with while it’s happening (usually a short time) in the conflict time, and ramifications of the conflict can be cleaned up in the post-conflict time. Narrowing in time reduces time-based assumptions.

Assumptions narrow even further when the conflict domain is narrowed in time and space together, limiting them to the where and when of the conflict. Like the intersection of two overlapping circles, the conflict domain is sharply narrowed at the intersection of space and time – a small space over a short time.

It’s best to create a picture of the conflict domain to understand it in space and time. Below (click to enlarge) is an example where abrasives (brown) in a stream of water (light blue) flow through a hole in a metal plate (gray) creating wear of the sidewall (in red). Pre-conflict time is before the abrasive particles enter the hole from the top; conflict time is while the particles contact the sidewall (conflict domain in red); post-conflict time is after the particles leave the hole. Only the right side of the metal place is shown to focus on the conflict domain. There is no conflict where the abrasive particles do not touch the sidewall.

Even if your radar is up and running, assumptions are tough to see – they’re translucent at best. But the techniques can help, though they’re difficult and uncomfortable, especially at first. But that’s the point. The techniques force you to argue with yourself over what you know and what you think you know. For a good start, try identify the two elements of the design that are not getting along, and make sure they’re in direct physical contact. If you’re looking for more of a challenge, try to draw a picture of the conflict domain. Your assumptions don’t stand a chance.

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski