Archive for the ‘Assumptions’ Category

What will they see?

When people look back on your life, what will they see?

When people look back on your life, what will they see?

When you’re dead and gone, what stories will your kids tell about you?

What stories will your coworkers tell?

How about your bosses?

Will they see your disagreement as mischievous or skillful?

Will they see your frustration as disruptive or caring?

Will they see your vehemence as disrespectful or passionate?

Will they see your divergent views as contrarian or well-intentioned?

Will they see your withholding as passive-aggressive or as the result of exhausting all other possibilities?

Will they see your tears as sadness for yourself or the company you care about deeply?

Will they see your “no’s” as curmudgeonly given or brave?

Will they see your dissent as destructive or constructive?

Will they see your frustration as immaturity or as others falling short of your high expectations?

Will they see your unpopular perspective as troublemaking or as the antidote to groupthink?

Will they see your positivity as fake or as the support that everyone needs to do their best work?

Here’s the thing: What matters is not what it looks like from the outside, but your intentions.

And another thing: Anyone that knows you knows your intentions.

Now, go out and do what you think is right. And do it like you mean it. And don’t look back.

And here’s a mantra: What people think about you is none of your business.

Bad Behavior or Unskillful Behavior?

What if you could see everyone as doing their best?

What if you could see everyone as doing their best?

When they are ineffective, what if you think they are using all the skills to the best of their abilities?

What changes when you see people as having a surplus of good intentions and a shortfall of skills?

If someone cannot recognize social cues and behaves accordingly, what does that say about them?

What does it say about you if you judge them as if they recognize those social cues?

Even if their best isn’t all skillful, what if you saw them as doing their best?

When someone treats you unskillfully, maybe they never learned how to behave skillfully.

When someone yells at you, maybe yelling is the only skill they were taught.

When someone treats you unskillfully, maybe that’s the only skill they have at their disposal.

And what if you saw them as doing their best?

Unskillful behavior cannot be stopped with punishment.

Unskillful behavior changes only when new skills are learned.

New skills are learned only when they are taught.

New skills are taught only when a teacher notices a yet-to-be-developed skillset.

And a teacher only notices a yet-to-be-developed skillset when they understand that the unskillful behavior is not about them.

And when a teacher knows the unskillful behavior is not about them, the teacher can teach.

And when teachers teach, new skills develop.

And as new skills develop, behavior becomes skillful.

It’s difficult to acknowledge unskillful behavior when it’s seen as mean, selfish, uncaring, and hurtful.

It’s easier to acknowledge unskillful behavior when it’s seen as a lack of skills set on a foundation of good intentions.

When you see unskillful behavior, what if you see that behavior as someone doing their best?

Unskillful behavior cannot change unless it is called by its name.

And once called by name, skillful behavior must be clearly described within the context that makes it skillful.

If you think someone “should” know their behavior is unskillful, you won’t teach them.

And when you don’t teach them, that’s about you.

If no one teaches you to hit a baseball, you never learn the skill of hitting a baseball.

When their bat always misses the ball, would you think the lesser of them? If you did, what does that say about you?

What if no one taught you how to crochet and you were asked to knit scarf? Even if you tried your best, you couldn’t do it. How could you possibly knit a scarf without developing the skill? How would you want people to see you? Wouldn’t you like to be seen as someone with good intentions that wants to be taught how to crochet?

If you were never taught how to speak French, should I see your inability to speak French as a character defect or as a lack of skill?

We are not born with skills. We learn them.

And we cannot learn skillful behavior unless we’re taught.

When we think they “should” know better, we assume they had good teachers.

When we think their unskillful behavior is about us, that’s about us.

When we punish unskillful behavior, it would be more skillful to teach new skills.

When we use prizes and rewards to change behavior, it would be more skillful to teach new skills.

When in doubt, it’s skillful to think the better of people.

Image credit — Steve Baker

Seeing Things as They Can’t Be

When there’s a big problem, the first step is to define what’s causing it. To do that, based on an understanding of the physics, a sequence of events is proposed and then tested to see if it replicates the problem. In that way, the team must understand the system as it is before the problem can be solved.

When there’s a big problem, the first step is to define what’s causing it. To do that, based on an understanding of the physics, a sequence of events is proposed and then tested to see if it replicates the problem. In that way, the team must understand the system as it is before the problem can be solved.

Seeing things as they are. The same logic applies when it’s time to improve an existing product or service. The first thing to do is to see the system as it is. But seeing things as they are is difficult. We have a tendency to see things as we want them or to see them in ways that make us look good (or smart). Or, we see them in a way that justifies the improvements we already know we want to make.

To battle our biases and see things as they are, we use tools such as block diagrams to define the system as it is. The most important element of the block diagram is clarity. The first revision will be incorrect, but it must be clear and explicit. It must describe things in a way that creates a singular understanding of the system. The best block diagrams can be interpreted only one way. More strongly, if there’s ambiguity or lack of clarity, the thing has not yet risen to the level of a block diagram.

The block diagram evolves as the team converges on a single understanding of things as they are. And with a diagram of things as they are, a solution is readily defined and validated. If when tested the proposed solution makes the problem go away, it’s inferred that the team sees things as they are and the solution takes advantage of that understanding to make the problem go away.

Seeing things as they may be. Even whey the solution fixes the problem, the team really doesn’t know if they see things as they are. Really, all they know is they see things as they may be. Sure, the solution makes the problem go away, but it’s impossible to really know if the solution captures the physics of failure. When the system is large and has a lot of moving parts, the team cannot see things as they are, rather, they can only see the system as it may be. This is especially true if the system involves people, as people behave differently based on how they feel and what happened to them yesterday.

There’s inherent uncertainty when working with larger systems and systems that involve people. It’s not insurmountable, but you’ve got to acknowledge that your understanding of the system is less than perfect. If your company is used to solving small problems within small systems, there will be little tolerance for the inherent uncertainty and associated unpredictability (in time) of a solution. To help your company make the transition, replace the language of “seeing things as they are” with “seeing things as they may be.” The same diagnostic process applies, but since the understanding of the system is incomplete or wrong, the proposed solutions cannot not be pre-judged as “this will work” and “that won’t work.” You’ve got to be open to all potential solutions that don’t contradict the system as it may be. And you’ve got to be tolerant of the inherent unpredictability of the effort as a whole.

Seeing things as they could be. To create something that doesn’t yet exist, something does things like never before, something altogether new, you’ve got to stand on top of your understanding of the system and jump off. Whether you see things as they are or as they may be, the new system will be different. It’s not about diagnosing the existing system; it’s about imagining the system as it could be. And there’s a paradox here. The better you understand the existing system, the more difficulty you’ll have imagining the new one. And, the more success the company has had with the system as it is, the more resistance you’ll feel when you try to make the system something it could be.

Seeing things as they could be takes courage – courage to obsolete your best work and courage to divest from success. The first one must be overcome first. Your body creates stress around the notion of making yourself look bad. If you can create something altogether better, why didn’t you do it last time? There’s a hit to the ego around making your best work look like it’s not all that good. But once you get over all that, you’ve earned the right to go to battle with your organization who is afraid to move away from the recipe responsible for all the profits generated over the last decade.

But don’t look at those fears as bad. Rather, look at them as indicators you’re working on something that could make a real difference. Your ego recognizes you’re working on something better and it sends fear into your veins. The organization recognizes you’re working on something that threatens the status quo and it does what it can to make you stop. You’re onto something. Keep going.

Seeing things as they can’t be. This is rarified air. In this domain you must violate first principles. In this domain you’ve got to run experiments that everyone thinks are unreasonable, if not ill-informed. You must do the opposite. If your product is fast, your prototype must be the slowest. If the existing one is the heaviest, you must make the lightest. If your reputation is based on the highest functioning products, the new offering must do far less. If your offering requires trained operators, the new one must prevent operator involvement.

If your most seasoned Principal Engineer thinks it’s a good idea, you’re doing it wrong. You’ve got to propose an idea that makes the most experienced people throw something at you. You’ve got to suggest something so crazy they start foaming at the mouth. Your concepts must rip out their fillings. Where “seeing things as they could be” creates some organizational stress, “seeing things as they can’t be” creates earthquakes. If you’re not prepared to be fired, this is not the domain for you.

All four of these domains are valuable and have merit. And we need them all. If there’s one message it’s be clear which domain you’re working in. And if there’s a second message it’s explain to company leadership which domain you’re working in and set expectations on the level of uncertainty and unpredictability of that domain.

Image credit – David Blackwell.

Wanting things to be different

Wanting things to be different is a good start, but it’s not enough. To create conditions for things to move in a new direction, you’ve got to change your behavior. But with systems that involve people, this is not a straightforward process.

To create conditions for the system to change, you must understand the system”s disposition – the lines along which it prefers to change.. And to do that, you’ve got to push on the system and watch its response. With people systems, the response is not knowable before the experiment.

If you expect to be able to predict how the system will respond, working with people systems can be frustrating. I offer some guidance here. With this work, you are not responsible for the system’s response, you are only responsible for how you respond to the system’s response.

If the system responds in a way you like, turn that experiment into a project to amplify the change. If the system responds in a way you dislike, unwind the experiment. Here’s a simple mantra – do more of what works and less of what doesn’t. (Thanks to Dave Snowden for this.)

If you don’t like how things are going, you have only one lever to pull. You can only change.your response to what you see and experience. You can respond by pushing on the system and responding to what you see or you can respond by changing what you think and feel about the system.

But keep in mind that you are part of the system. And maybe the system is running an experiment on you. Either way, your only choice is to choose how to respond.

Purposeful Procrastination

There’s a useful trick when you want to do new work. It has some of the characteristics of procrastination, but it’s different. With procrastination, the problem solver waits to start the solving until it’s almost impossible to meet the deadline. The the solver uses the unreasonable deadline to create internal pressure so they can let go of all the traditional solving approaches. With no time for traditional approaches, the solver must let go of what worked and try a new approach.

There’s a useful trick when you want to do new work. It has some of the characteristics of procrastination, but it’s different. With procrastination, the problem solver waits to start the solving until it’s almost impossible to meet the deadline. The the solver uses the unreasonable deadline to create internal pressure so they can let go of all the traditional solving approaches. With no time for traditional approaches, the solver must let go of what worked and try a new approach.

The heart of the IBE is the Design Challenge, where a team with diverse perspective is brought together by a facilitator to solve a problem in five minutes. The unreasonable time constraint generates all the goodness that comes with procrastination, but, because it’s a problem solving exercise, there’s no drama. And like with procrastination, the teams deliver unimaginable results within an unrealistic time constraint.

Seeing What Isn’t There

It’s relatively straightforward to tell the difference between activities that are done well and those that are done poorly. Usually sub-par activities generate visual signals to warn us of their misbehavior. A bill isn’t paid, a legal document isn’t signed or the wrong parts are put in the box. Though the specifics vary with context, the problem child causes the work product to fall off the plate and make a mess on the floor.

It’s relatively straightforward to tell the difference between activities that are done well and those that are done poorly. Usually sub-par activities generate visual signals to warn us of their misbehavior. A bill isn’t paid, a legal document isn’t signed or the wrong parts are put in the box. Though the specifics vary with context, the problem child causes the work product to fall off the plate and make a mess on the floor.

We have tools to diagnose the fundamental behind the symptom. We can get to root cause. We know why the plate was dropped. We know how to define the corrective action and implement the control mechanism so it doesn’t happen again. We patch up the process and we’re up and running in no time. This works well when there’s a well-defined in place, when process is asked to do what it did last time, when the inputs are the same as last time and when the outputs are measured like they were last time.

However, this linear thinking works terribly when the context changes. When the old processes are asked to do new work, the work hits the floor like last time, but the reason it hits the floor is fundamentally different. This time, it’s not that an activity was done poorly. Rather, this time there’s something missing altogether. And this time our linear-thinker toolbox won’t cut it. Sure, we’ll try with all our Six Sigma might, but we won’t get to root cause. Six Sigma, lean and best practices can fix what’s broken, but none of them can see what isn’t there.

When the context changes radically, the work changes radically. New-to-company activities are required to get the new work done. New-to-industry tools are needed to create new value. And, sometimes, new-to-world thinking is the only thing that will do. The trick isn’t to define the new activity, choose the right new tool or come up with the new thinking. The trick is to recognize there’s something missing, to recognize there’s something not there, to recognize there’s a need for something new. Whether it’s an activity, a tool or new thinking, we’ve got to learn to see what’s not there.

Now the difficult part – how to recognize there’s something missing. You may think the challenging part is to figure out what’s needed to fill the void, but it isn’t. You can’t fill a hole until you see it as a hole. And once everyone agrees there’s a hole, it’s pretty easy to buy the shovels, truck in some dirt and get after it. But if don’t expect holes, you won’t see them. Sure, you’ll break your ankle, but you won’t see the hole for what it is.

If the work is new, look for what’s missing. If the problem is new, watch out for holes. If the customer is new, there will be holes. If the solution is new, there will be more holes.

When the work is new, you will twist your ankle. And when you do, grab the shovels and start to put in place what isn’t there.

Image credit – Tony Atler

The Courage To Speak Up

If you see things differently than others, congratulations. You’re thinking for yourself.

If you see things differently than others, congratulations. You’re thinking for yourself.

If you find yourself pressured into thinking like everyone else, that’s a sign your opinion threatens. It’s too powerful to be dismissed out-of-hand, and that’s why they want to shut you up.

If the status quo is angered by your theory, you’re likely onto something. Stick to your guns.

If your boss doesn’t want to hear your contrarian opinion, that’s because it cannot be easily dismissed. That’s reason enough to say it.

If you disagree in a meeting and your sentiment is actively dismissed, dismiss the dismisser. And say it again.

If you’re an active member of the project and you are not invited to the meeting, take it as a compliment. Your opinion is too powerful to defend against. The only way for the group-think to survive is to keep you away from it. Well done.

If your opinion is actively and repeatedly ignored, it’s too powerful to be acknowledged. Send a note to someone higher up in the organization. And if that doesn’t work, send it up a level higher still. Don’t back down.

If you look into the future and see a train wreck, set up a meeting with the conductor and tell them what you see.

When you see things differently, others will try to silence you and tell you you’re wrong. Don’t believe them. The world needs people like you who see things as they are and have the courage to speak the truth as they see it.

Thank you for your courage.

Image credit – Cristian V.

Choosing What To Do

In business you’ve got to do two things: choose what to do and choose how to do it well. I’m not sure which is more important, but I am sure there’s far more written on how to do things well and far less clarity around how to choose what to do.

In business you’ve got to do two things: choose what to do and choose how to do it well. I’m not sure which is more important, but I am sure there’s far more written on how to do things well and far less clarity around how to choose what to do.

Choosing what to do starts with understanding what’s being done now. For technology, it’s defining the state-of-the-art. For the business model, it’s how the leading companies are interacting with customers and which functions they are outsourcing and which they are doing themselves. In neither case does what’s being done define your new recipe, but in both cases it’s the first step to figuring how you’ll differentiate over the competition.

Every observation of the state-of-the-art technologies and latest business models is a snapshot in time. You know what’s happening at this instant, but you don’t know what things will look like in two years when you launch. And that’s not good enough. You’ve got to know the improvement trajectories; you’ve got to know if those trajectories will still hold true when you’ll launch your offering; and, if they’re out of gas, you’ve got to figure out the new improvement areas and their trajectories.

You’ve got to differentiate over the in-the-future competition who will constantly improve over the next two years, not the in-the-moment competition you see today.

For technology, first look at the competitions’ websites. For their latest product or service, figure out what they’re proud of, what they brag about, what line of goodness it offers. For example, is it faster, smaller, lighter, more powerful or less expensive? Then, look at the product it replaced and what it offered. If the old was faster than the one it replaced and the newest one was faster still, their next one will try to be faster. But if the old one was faster than the one it replaced and the newest one is proud of something else, it’s likely they’ll try to give the next one more of that same something else.

And the rate of improvement gives another clue. If the improvement is decreasing over time (old product to new product), it’s likely the next one will improve on a new line of goodness. If it’s still accelerating, expect more of what they did last time. Use the slope to estimate the magnitude of improvement two years from now. That’s what you’ve got to be better than.

And with business models, make a Wardley Map. On the map, place the elements of the business ecosystem (I hate that word) and connect the elements that interact with each other. And now the tricky part. Move to the right the mature elements (e.g., electrical power grid), move to the middle the immature elements (things that are clunky and you have to make yourself) and move to the middle the parts you can buy from others (products). There’s a north-south element to the maps, but that’s for another time.

The business model is defined by which elements the company does itself, which it buys from others and which new ones they create in their labs. So, make a model for each competitor. You’ll be able to see their business model visually.

Now, which elements to work on? Buy the ones you can buy (middle), improve the immature ones on the far left so they move toward the central region (product) and disrupt the lazy utilities (on the right) with some crazy technology development and create something new on the far left (get something running in the lab).

Choosing what to work on starts with Observation of what’s going on now. Then, that information is Oriented with analysis, synthesis and diverse perspective. Then, using the best frameworks you know, a Decision is made. And then, and only then, can you Act.

And there you have it. The makings of an OODA loop-based methodology for choosing what to do.

For a great podcast on John Boyd, the father of the OODA loop, try this one.

And for the deepest dive on OODA (don’t start with this one) see Osinga – Science, Strategy and War.

Testing the Business Model

Sometimes we get caught up in the details when we should be working on the foundation. Here’s a rule: If the underlying foundation is not secure, don’t bother working on anything else.

Sometimes we get caught up in the details when we should be working on the foundation. Here’s a rule: If the underlying foundation is not secure, don’t bother working on anything else.

If you’re working on a couple new technologies, but the overall business model won’t be profitable, don’t work on the new technologies. Instead, figure out a business model that is profitable, then do what it takes (technology, simplification, process improvement) to make it happen. But, often, that’s not what we do.

Often, we put the cart before the horse. We create projects to make prototypes that demonstrate a new technology, but the whole business premise is built on quicksand. There’s a reason why foundations are made from concrete and not quicksand. It’s because you can build on top of a base made of concrete. It supports the load. It doesn’t crack, nor does it fall apart. Think Pyramid of Giza.

Because foundations are big and expensive they can be difficult and expensive to test. For example, if an innovation is based on a new foundation, say, a new business model, building a physical prototype of the new business model is too expensive and the testing will not happen. And what usually happens is the foundation goes untested, the higher level technology work is done, the commercialization work is completed and the business model fails because it wasn’t solid.

But you don’t have to build a full-scale prototype of the Pyramid of Giza to test if a pyramid will stand the test of time. You can build a small one and test it, or you can run an analysis of some sort to understand if the pyramid will support the weight. But what if you want to test a new business model, a business model that has never been done before, using new products and services that have never seen the light of day? What do you do? In this case, it doesn’t make sense to make even a scale model. But it does make sense to create a one page sales tool that describes the whole thing and it does make sense to show it to potential customers and ask them what they think about it.

The open question with all new things is – will customers like it enough to buy it. And, it’s no different with the business model. Instead of creating a new website, staffing up, creating new technologies and products, create a one-page sales tool that describes the new elements and show it to potential customers. Distill the value proposition into language people can understand, describe the novelty that fuels the value, capture it on one page, show it to customers, and listen.

And don’t build a single, one-page sales tool, build two or three versions. And then, ask customers what they think. Odds are, they’ll ask you questions you didn’t think they’d ask. Odds are, they’ll see it differently than you do. And, odds are, you’ll have to incorporate their feedback into an improved version of the business model. The bad new is you didn’t get it right. The good news is you didn’t have to staff up and build the whole business model, create the technologies and launch the products. And more good news – you can quickly modify the one-page sales tool and go back to the customers and ask them what they think. And you can do this quickly and inexpensively.

Don’t develop the technology until you know the underlying business model will be profitable. Don’t staff up until you know if the business model holds water. Don’t launch the new products until you verify customers will buy what you want to sell.

Creating a new business model from scratch is an expensive proposition. Don’t build it until you invest in validating it’s worth building.

The worst way to validate a business model is by building it.

Image credit – David Stanley

With novelty, less can be more.

When it’s time to create something new, most people try to imagine the future and then put a plan together to make it happen. There’s lots of talk about the idealize future state, cries for a clean slate design or an edict for a greenfield solution. Truth is, that’s a recipe for disaster. Truth is, there is no such thing as a clean slate or green field. And because there are an infinite number of future states, it’s highly improbable your idealized future state is the one the universe will choose to make real.

When it’s time to create something new, most people try to imagine the future and then put a plan together to make it happen. There’s lots of talk about the idealize future state, cries for a clean slate design or an edict for a greenfield solution. Truth is, that’s a recipe for disaster. Truth is, there is no such thing as a clean slate or green field. And because there are an infinite number of future states, it’s highly improbable your idealized future state is the one the universe will choose to make real.

To create something new, don’t look to the future. Instead, sit in the present and understand the system as it is. Define the major elements and what they do. Define connections among the elements. Create a functional diagram using blocks for the major elements, using a noun to name each block, and use arrows to define the interactions between the elements, using a verb to label each arrow. This sounds like a complete waste of time because it’s assumed that everyone knows how the current state system behaves. The system has been the backbone of our success, of course everyone knows the inputs, the outputs, who does what and why they do it.

I have created countless functional models of as-is systems and never has everyone agreed on how it works. More strongly, most of the time the group of experts can’t even create a complete model of the as-is system without doing some digging. And even after three iterations of the model, some think it’s complete, some think it’s incomplete and others think it’s wrong. And, sometimes, the team must run experiments to determine how things work. How can you imagine an idealized future state when you don’t understand the system as it is? The short answer – you can’t.

And once there’s a common understanding of the system as it is, if there’s a call for a clean sheet design, run away. A call for a clean sheet design is sure fire sign that company leadership doesn’t know what they’re doing. When creating something new it’s best to inject the minimum level of novelty and reuse the rest (of the system as it is). If you can get away with 1% novelty and 99% reuse, do it. Novelty, by definition, hasn’t been done before. And things that have never been done before don’t happen quickly, if they happen at all. There’s no extra credit for maximizing novelty. Think of novelty like ghost pepper sauce – a little goes a long way. If you want to know how to handle novelty, imagine a clean sheet design and do the opposite.

Greenfield designs should be avoided like the plague. The existing system has coevolved with its end users so that the system satisfies the right needs, the users know how to use the system and they know what to expect from it. In a hand-in-glove way, the as-is system is comfortable for end users because it fits them. And that’s a big deal. Any deviation from baseline design (novelty) will create discomfort and stress for end users, even if that novelty is responsible for the enhancement you’re trying to deliver. Novelty violates customer expectations and violating customer expectations is a dangerous game. Again, when you think novelty, think ghost peppers. If you want to know how to handle novelty, imagine a green field and do the opposite.

This approach is not incrementalism. Where you need novelty, inject it. And where you don’t need it, reuse. Design the system to maximize new value but do it with minimum novelty. Or, better still, offer less with far less. Think 90% of the value with 10% of the cost.

Image credit – Laurie Rantala

The one good way to change behavior.

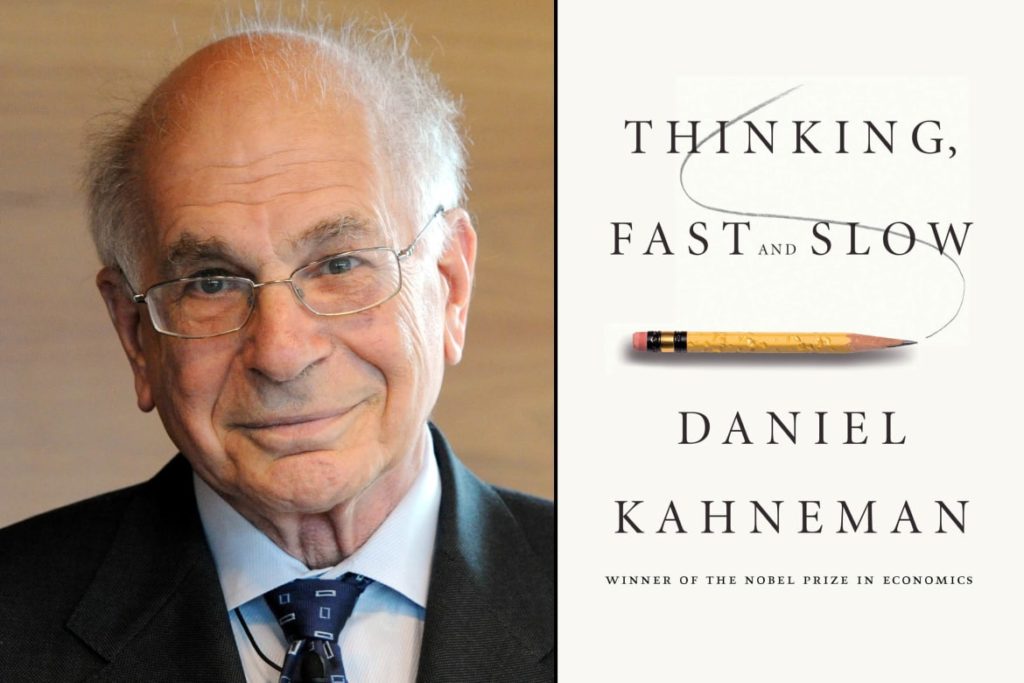

There’s one good way to change behavior. But don’t take my word for it, take Daniel Kahneman’s, psychologist who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences. In Freakonomics Radio’s podcast How to Launch a Behavioral Change Revolution, Kahneman explains how to achieve change in behavior. His explanation is short [30:35 – 35:21] and good.

There’s one good way to change behavior. But don’t take my word for it, take Daniel Kahneman’s, psychologist who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences. In Freakonomics Radio’s podcast How to Launch a Behavioral Change Revolution, Kahneman explains how to achieve change in behavior. His explanation is short [30:35 – 35:21] and good.

Kahneman describes a theory of Kurt Lewin, his academic grandfather, where behavior is an equilibrium, a balance between driving forces that push for change and restraining forces that hold back change. Kahneman goes on to describe Lewin’s insight. “Lewin’s insight was that if you want to achieve change in behavior, there is one good way to do it and one bad way. The good way is by diminishing restraining forces, not by increasing the driving forces. That turns out to be profoundly non-intuitive.”

Usually, when we want someone to change, we push them in the direction we want them to go. Kahneman says this approach is natural, but ineffective. He offers a different approach – “Instead of asking how can I get him or her to do it, it starts with a question of why isn’t she doing it already? Go one-by-one, systematically, and you ask ‘What can I do to make it easier for that person to move?’”

What would happen if instead of pushing someone to change, you understand what’s in the way and eliminated the restraining force? I don’t know, but I’m going to give it a try.

Kahneman goes on to describe how to make things easier for a person to move. He says “…the way to make things easier is almost always by controlling the individual’s environment…by just making it easier.” Sounds pretty simple – change people’s environment to make it easier for them to move toward the desired behavior. But, we don’t do it that way.

Kahneman gives more detail. “Are there incentives that work against it? Let’s change the incentives.” And then he gives a simple example. “I want to influence B, but there is A in the background and it’s A who is a restraining force on B, let’s work on A, not on B.”

I urge you to listen to the short segment to hear Kahneman’s words for yourself. His ideas really hit home when you hear them from him.

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski