Archive for the ‘Assumptions’ Category

Swimming In New Soup

You know the space is new when you don’t have the right words to describe the phenomenon.

You know the space is new when you don’t have the right words to describe the phenomenon.

When there are two opposite sequences of events and you think both are right, you know the space is new.

You know you’re thinking about new things when the harder you try to figure it out the less you know.

You know the space is outside your experience but within your knowledge when you know what to do but you don’t know why.

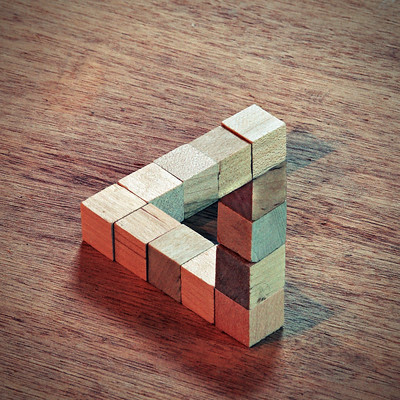

When you can see the concept in your head but can’t drag it to the whiteboard, you’re swimming in new soup.

When you come back from a walk with a solution to a problem you haven’t yet met, you’re circling new space.

And it’s the same when know what should be but it isn’t – circling new space.

When your old tricks are irrelevant, you’re digging in a new sandbox.

When you come up with a new trick but the audience doesn’t care – new space.

When you know how an experiment will turn out and it turns out you ran an irrational experiment – new space.

When everyone disagrees, the disagreement is a surrogate for the new space.

It’s vital to recognize when you’re swimming in a new space. There is design freedom, new solutions to new problems, growth potential, learning, and excitement. There’s acknowledgment that the old ways won’t cut it. There’s permission to try.

And it’s vital to recognize when you’re squatting in an old space because there’s an acknowledgment that the old ways haven’t cut it. And there’s permission to wander toward a new space.

Image credit — Tambaco The Jaguar

Some Ifs and Thens To Get You Through Your Day

If you didn’t get what you wanted, why not try wanting what you got?

If you didn’t get what you wanted, why not try wanting what you got?

If the timing isn’t right, what can you change so it is right?

If it could get you in trouble, might you be on to something?

If it’s impossible, don’t bother.

If it’s easy, let someone else do it.

If there’s no possibility of bad things, there’s no possibility of magic.

If you need trust but have not yet secured it, declare failure and do something else.

If there is no progress, don’t push. Move the blocking agent out of the way.

If you don’t know where the cost is, you can’t design it out.

If the timing isn’t right, why didn’t you do it sooner?

If the project went flawlessly, you didn’t try to do anything meaningful.

If you know some people won’t like it, isn’t that reason enough to do it?

If it’s almost impossible, give it a go.

If it’s easy, teach someone else to do it.

If you don’t know where the waste is, you can’t get rid of it.

If you don’t need trust, it’s the perfect time to build it.

If you try the hardest thing first and it doesn’t work, at least you avoid wasting time on the easy stuff.

If you don’t know the number of parts in your product, you have too many.

If the product came out perfectly, you took too long.

If you don’t give it a go, how can you know it’s impossible?

If trust is in short supply, supply it.

If it’s easy, do something else.

If forgiveness is so much better than permission, why do we like to do things under the radar?

If bad things didn’t happen, try harder next time.

Image credit — Gabriel Caparó

What’s in the way of the newly possible?

When “it’s impossible” it means it “cannot be done.” But maybe “impossible” means “We don’t yet know how to do it.” Or “We don’t yet know if others have done it before.”

When “it’s impossible” it means it “cannot be done.” But maybe “impossible” means “We don’t yet know how to do it.” Or “We don’t yet know if others have done it before.”

What does it take to transition from impossible to newly possible? What must change to move from the impossible to the newly possible?

Context-Specific Impossibility. When something works in one industry or application but doesn’t work in another, it’s impossible in that new context. But usually, almost all the elements of the system are possible and there are one or two elements that don’t work due to the new context. There’s an entire system that’s blocked from possibility due to the interaction between one or two system elements and an environmental element of the new context. The path to the newly possible is found in those tightly-defined interactions. Ask yourself these questions: Which system elements don’t work and what about the environment is preventing the migration to the newly possible? And let the intersection focus your work.

History-Specific Impossibility. When something didn’t work when you tried it a decade ago, it was impossible back then based on the constraints of the day. And until those old constraints are revisited, it is still considered impossible today. Even though there has been a lot of progress over the last decades, if we don’t revisit those constraints we hold onto that old declaration of impossibility. The newly possible can be realized if we search for new developments that break the old constraints. Ask yourself: Why didn’t it work a decade ago? What are the new developments that could overcome those problems? Focus your work on that overlap between the old problems and the new developments.

Emotionally-Specific Impossibility. When you believe something is impossible, it’s impossible. When you believe it’s impossible, you don’t look for solutions that might birth the newly possible. Here’s a rule: If you don’t look for solutions, you won’t find them. Ask yourself: What are the emotions that block me from believing it could be newly possible? What would I have to believe to pursue the newly possible? I think the answer is fear, but not the fear of failure. I think the fear of success is a far likelier suspect. Feel and acknowledge the emotions that block the right work and do the right work. Feel the fear and do the work.

The newly possible is closer than you think. The constraints that block the newly possible are highly localized and highly context-specific. The history that blocks the newly possible is no longer applicable, and it’s time to unlearn it. Discover the recent developments that will break the old constraints. And the emotions that block the newly possible are just that – emotions. Yes, it feels like the fear will kill you, but it only feels like that. Bring your emotions with you as you do the right work and generate the newly possible.

image credit – gfpeck

Do you create the conditions for decisions to be made without you?

What does your team do when you’re not there? Do they make decisions or wait for you to come back so you can make them?

What does your team do when you’re not there? Do they make decisions or wait for you to come back so you can make them?

If your team makes an important decision while you’re out of the office, do you support or criticize them? Which response helps them stand taller? Which is most beneficial to the longevity of the company?

If other teams see your team make decisions while you are on vacation, doesn’t that make it easier for those other teams to use their good judgment when their leader is on vacation?

If a team waits for their leader to return before making a decision, doesn’t that slow progress? Isn’t progress what companies are all about?

When you’re not in the office, does the organization reach out directly to your team directly? Or do they wait until they can ask your permission? If they don’t reach out directly, isn’t that a reflection on you as the leader? Is your leadership helping or hindering progress? How about the professional growth of your team members?

Does your team know you want them to make decisions and use their best judgment? If not, tell them. Does the company know you want them to reach out directly to the subject matter experts on your team? If not, tell them.

If you want your company to make progress, create the causes and conditions for good decisions to be made without you.

Image credit – Conall

Is the timing right?

If there is no problem, it is too soon for a solution.

If there is no problem, it is too soon for a solution.

But when there is consensus on a problem, it may be too late to solve it.

If a powerful protector of the Status Quo is to retire in a year, it may be too early to start work on the most important sacrilege.

But if the sacrilege can be done under cover, it may be time to start.

It may be too soon to put a young but talented person in a leadership position if the team is also green.

But it may be the right time to pair the younger person with a seasoned leader and move them both to the team.

When the business model is highly profitable, it may be too soon to demonstrate a more profitable business model that could obsolete the existing one.

But new business models take a long time to gestate and all business models have half-lives, so it may be time to demonstrate the new one.

If there is no budget for a project, it is too soon for the project.

But the budget may never come, so it is probably time to start the project on the smallest scale.

When the new technology becomes highly profitable, it may be too soon to demonstrate the new technology that makes it obsolete.

But like with business models, all technologies have half-lives, so it may be time to demonstrate the new technology.

The timing to do new work or make a change is never perfect. But if the timing is wrong, wait. But don’t wait too long.

If the timing isn’t right, adjust the approach to soften the conflict, e.g., pair a younger leader with a seasoned leader and move them both.

And if the timing is wrong but you think the new work cannot wait, start small.

And if the timing is horrifically wrong, start smaller.

It’s good to have experience, until the fundamentals change.

We use our previous experiences as context for decisions we make in the present. When we have a bad experience, the experience-context pair gets stored away in our memory so that we can avoid a similar bad outcome when a similar context arises. And when we have a good experience, or we’re successful, that memory-context pair gets stored away for future reuse. This reuse approach saves time and energy and, most of the time keeps us safe. It’s nature’s way of helping us do more of what works and less of what doesn’t.

We use our previous experiences as context for decisions we make in the present. When we have a bad experience, the experience-context pair gets stored away in our memory so that we can avoid a similar bad outcome when a similar context arises. And when we have a good experience, or we’re successful, that memory-context pair gets stored away for future reuse. This reuse approach saves time and energy and, most of the time keeps us safe. It’s nature’s way of helping us do more of what works and less of what doesn’t.

The system works well when we correctly match the historical context with today’s context and the system’s fundamentals remain unchanged. There are two potential failure modes here. The first is when we mistakenly map the context of today’s situation with a memory-context pair that does not apply. With this, we misapply our experience-based knowledge in a context that demands different knowledge and different decisions. The second (and more dangerous) failure mode is when we correctly identify the match between past and current contexts but the rules that underpin the context have changed. Here, we feel good that we know how things will turn out, and, at the same time, we’re oblivious to the reality that our experience-based knowledge is out of date.

“If a cat sits on a hot stove, that cat won’t sit on a hot stove again. That cat won’t sit on a cold stove either. That cat just don’t like stoves.” Mark Twain

If you tried something ten years ago and it failed, it’s possible that the underpinning technology has changed and it’s time to give it another try.

If you’ve been successful doing the same thing over the last ten years, it’s possible that the underpinning business model has changed and it’s time to give a different one a try.

“Hissing cat” by Consumerist Dot Com is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

How To Solve Transparent Problems

One of the best problems to solve for your customers is the problem they don’t know they have. If you can pull it off, you will create an entirely new value proposition for them and enable them to do things they cannot do today. But the problem is they can’t ask you to solve it because they don’t know they have it.

One of the best problems to solve for your customers is the problem they don’t know they have. If you can pull it off, you will create an entirely new value proposition for them and enable them to do things they cannot do today. But the problem is they can’t ask you to solve it because they don’t know they have it.

To identify problems customs can’t see, you’ve got to watch them go about their business. You’ve got to watch all aspects of their work and understand what they do and why they do it that way. And it’s their why that helps you find the transparent problems. When they tell you their why, they tell you the things they think cannot change and the things they consider fundamental constraints. Their whys tell you what they think is unchangeable. And from their perspective, they’re right. These things are unchangeable because they don’t know what’s possible with new technologies.

Once you know their unchangeable constraints, choose one to work on and turn it into a tight problem statement. Then use your best tools and methods to solve it. Once solved, you’ve got to make a functional prototype and show them in person. Without going back to them with a demonstration of a functional prototype, they won’t believe you. Remember, you did something they didn’t think was possible and changed the unchangeable.

When demonstrating the prototype to the customer, just show it in action. Don’t describe it, just show them and let them ask questions. Listen to their questions so you can see the prototype through their eyes. And to avoid leading the witness, limit yourself to questions that help you understand why they see the prototype as they do. The way they see the prototype will be different than your expectations, and that difference is called learning. And if you find yourself disagreeing with them, you’re doing it wrong.

This first prototype won’t hit the mark exactly, but it will impress the customer and it will build trust with them. And because they watched the prototype in action, they will be able to tell you how to improve it. Or better yet, with their newfound understanding of what’s possible, they might be able to see a more meaningful transparent problem that, once solved, could revolutionize their industry.

Customers know their work and you know what’s possible. And prototypes are a great way to create the future together.

“Transparent” by Rene Mensen is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

What you do next is up to you.

If you don’t know why you’re doing what you’re doing, you can try to remember why you started the whole thing or you can do something else. Either can remedy things, but how do you choose between them? If you’ve forgotten your “why”, maybe it’s worth forgetting or maybe something else temporarily came up that pushed your still-important why underground for a short time. If it’s worth forgetting, maybe it’s time for something else. And if it’s worth remembering, maybe it’s time to double down. Only you can choose.

If you don’t know why you’re doing what you’re doing, you can try to remember why you started the whole thing or you can do something else. Either can remedy things, but how do you choose between them? If you’ve forgotten your “why”, maybe it’s worth forgetting or maybe something else temporarily came up that pushed your still-important why underground for a short time. If it’s worth forgetting, maybe it’s time for something else. And if it’s worth remembering, maybe it’s time to double down. Only you can choose.

If you still remember why you’re doing what you’re doing, you can ask yourself if your why is still worth its salt or if something changed, either inside you or in your circumstances, that has twisted your why to something beyond salvage. If your why is still as salty as ever, maybe it’s right to stay the course. But if it’s still as salty as ever but you now think it’s distasteful, maybe it’s time for a change.

When you do what you did last time, are you more efficient or more dissatisfied, or both? And if you imagine yourself doing it again, do you look forward to more efficiency or predict more dissatisfaction? These questions can help you decide whether to keep things as they are or change them.

What have you learned over the last year? Whether your list is long or if it’s short, it’s a good barometer to inform your next chapter.

What new skills have you mastered over the last year? Is the list long or short? If you don’t want to grow your mastery, keep things as they are.

Do the people you work with inspire you or bring you down? Are you energized or depleted by them? If you’re into depletion, there’s no need to change anything.

Do you have more autonomy than last year? And how do you feel about that? Let your answers guide your future.

What is the purpose behind what you do? Is it aligned with your internal compass? These two questions can bring clarity.

You’re the only one who can ask yourself these questions; you’re the only one who can decide if you like the answers; and you’re the only one who is responsible for what you do next. What you do next is up to you.

“Fork in the road” by Kai Hendry is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

How To Be Novel

By definition, the approach that made you successful will become less successful over time and, eventually, will run out of gas. This fundamental is not about you or your approach, rather it’s about the nature of competition and evolution. There’s an energy that causes everything to change, grow and improve and your success attracts that energy. The environment changes, the people change, the law changes and companies come into existence that solve problems in better and more efficient ways. Left unchanged, every successful business endeavor (even yours) has a half-life.

By definition, the approach that made you successful will become less successful over time and, eventually, will run out of gas. This fundamental is not about you or your approach, rather it’s about the nature of competition and evolution. There’s an energy that causes everything to change, grow and improve and your success attracts that energy. The environment changes, the people change, the law changes and companies come into existence that solve problems in better and more efficient ways. Left unchanged, every successful business endeavor (even yours) has a half-life.

If you want to extend the life of your business endeavor, you’ve got to be novel.

By definition, if you want to grow, you’ve got to raise your game. You’ve got to do something different. You can’t change everything, because that’s inefficient and takes too long. So, you’ve got to figure out what you can reuse and what you’ve got to reinvent.

If you want to grow, you’ve got to be novel.

Being novel is necessary, but expensive. And risky. And scary. And that’s why you want to add just a pinch of novelty and reuse the rest. And that’s why you want to try new things in the smallest way possible. And that’s why you want to try things in a time-limited way. And that’s why you want to define what success looks like before you test your novelty.

Some questions and answers about being novel:

Is it easy to be novel? No. It’s scary as hell and takes great emotional strength.

Can anyone be novel? Yes. But you need a good reason or you’ll do what you did last time.

How can I tell if I’m being novel? If you’re not scared, you’re not being novel. If you know how it will turn out, you’re not being novel. If everyone agrees with you, you’re not being novel.

How do I know if I’m being novel in the right way? You cannot. Because it’s novel, it hasn’t been done before, and because it hasn’t been done before there’s no way to predict how it will go.

So, you’re saying I can’t predict the outcome of being novel? Yes.

If I can’t predict the outcome of being novel, why should I even try it? Because if you don’t, your business will go away.

Okay. That last one got my attention. So, how do I go about being novel? It depends.

That’s not a satisfying answer. Can you do better than that? Well, we could meet and talk for an hour. We’d start with understanding your situation as it is, how this current situation came to be, and talk through the constraints you see. Then, we’d talk about why you think things must change. I’d then go away for a couple of days and think about things. We’d then get back together and I’d share my perspective on how I see your situation. Because I’m not a subject matter expert in your field, I would not give you answers, but, rather, I’d share my perspective that you could use to inform your choice on how to be novel.

“Giraffe trying to catch a twig with her tongue” by Tambako the Jaguar is licensed under CC BY-ND 2.0

How To See What’s Missing

With one eye open and the other closed, you have no depth perception. With two eyes open, you see in three dimensions. This ability to see in three dimensions is possible because each eye sees from a unique perspective. The brain knits together the two unique perspectives so you can see the world as it is. Or, as your brain thinks it is, at least.

With one eye open and the other closed, you have no depth perception. With two eyes open, you see in three dimensions. This ability to see in three dimensions is possible because each eye sees from a unique perspective. The brain knits together the two unique perspectives so you can see the world as it is. Or, as your brain thinks it is, at least.

And the same can be said for an organization. When everyone sees things from a single perspective, the organization has no depth perception. But with at least two perspectives, the organization can better see things as they are. The problem is we’re not taught to see from unique perspectives.

With most presentations, the material is delivered from a single perspective with the intention of helping everyone see from that singular perspective. Because there’s no depth to the presentation, it looks the same whether you look at it with one eye or two. But with some training, you can learn how to see depth even when it has purposely been scraped away.

And it’s the same with reports, proposals, and plans. They are usually written from a single perspective with the objective of helping everyone reach a single conclusion. But with some practice, you can learn to see what’s missing to better see things as they are.

When you see what’s missing, you see things in stereo vision.

Here are some tips to help you see what’s missing. Try them out next time you watch a presentation or read a report, proposal, or plan.

When you see a WHAT, look for the missing WHY on the top and HOW on the bottom. Often, at least one slice of bread is missing from the why-what-how sandwich.

When you see a HOW, look for the missing WHO and WHEN. Usually, the bread or meat is missing from the how-who-when sandwich.

Here’s a rule to live by: Without finishing there can be no starting.

When you see a long list of new projects, tasks, or initiatives that will start next year, look for the missing list of activities that would have to stop in order for the new ones to start.

When you see lots of starting, you’ll see a lot of missing finishing.

When you see a proposal to demonstrate something for the first time or an initial pilot, look for the missing resources for the “then what” work. After the prototype is successful, then what? After the pilot is successful, then what? Look for the missing “then what” resources needed to scale the work. It won’t be there.

When you see a plan that requires new capabilities, look for the missing training plan that must be completed before the new work can be done well. And look for the missing budget that won’t be used to pay for the training plan that won’t happen.

When you see an increased output from a system, look for the missing investment needed to make it happen, the missing lead time to get approval for the missing investment, and the missing lead time to put things in place in time to achieve the increased output that won’t be realized.

When you see a completion date, look for the missing breakdown of the work content that wasn’t used to arbitrarily set the completion date that won’t be met.

When you see a cost reduction goal, look for the missing resources that won’t be freed up from other projects to do the cost reduction work that won’t get done.

It’s difficult to see what’s missing. I hope you find these tips helpful.

“missing pieces” by LeaESQUE is licensed under CC BY-ND 2.0

Regardless of the problem, the solution lives inside you.

If you want things to be different than they are, you have a problem. And if you want things to stay the same, you also have a problem. Either way, you have a problem. You can complain, you can do something about it, or you can accept things as they are.

If you want things to be different than they are, you have a problem. And if you want things to stay the same, you also have a problem. Either way, you have a problem. You can complain, you can do something about it, or you can accept things as they are.

Complaining can be fun for a while, then it turns sour. Doing something about it can take a lot of time and energy, and it’s difficult to know what to do. Accepting things as they are can be a challenge because that means it’s time to change your perspective. But it’s your choice. So, what do you choose?

What does it look like to accept things as they are AND do something about it?

If you want someone to be different than they are, you have a problem. And if you want them to stay the same, you have a different problem. Either way, you have a problem. You can complain about them, you can do something about it, or you can accept them as they are.

Complaining about people can be fun, but only in small doses. Doing something about it, well, that’s difficult because people will do what they want to do, not what you want them to do. Accepting people as they are is difficult because it means you have to look inside and change yourself. But it’s your choice. So, what do you choose?

What does it look like to accept people as they are AND to do something that makes things better for all?

If you have a problem with things changing, the solution lives inside you. Things change. That’s what they do. And if you have a problem with things staying the same, the solution lives inside you. Things stay the same. That’s what they do. Either way, the solution lives inside you, and it’s time to look inside.

How would it feel to own your problem and look inside for the solution?

If you have a problem because you want people to be different, the solution lives inside you. People behave the way they want to behave, not the way you want them to behave. And if you have a problem because you want people to stay the same, the solution lives inside you. People change. That’s what they do. Either way, the problem is you, and it’s time to look inside for the solution.

How would it feel to accept people as they are and look inside to solve your problem?

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski