It’s not about failing fast; it’s about learning fast.

No one has ever been promoted by failing fast. They may have been promoted because they learned something important from an experiment that delivered unexpected results, but that’s fundamentally different than failure. That’s learning.

Failure, as a word, has the strongest negative connotations. Close your eyes and imagine a failure. Can you imagine a scenario where someone gets praised or promoted for that failure? I think not. It’s bad when you fail to qualify for a race. It’s bad when you fail to get that new job. It’s bad when driving down the highway the transmission fails fast. If you squint, sometimes you can see a twinkle of goodness in failure, but it’s still more than 99% bad.

When it’s bad for people’s careers, they don’t do it. Failure is like that. If you want to motivate people or instill a new behavior, I suggest you choose a word other than failure.

Learning, as a word, has highly positive connotations. Children go to school to learn, and that’s good. People go to college to learn, and that’s good. When people learn new things they can do new things, and that’s good. Learning is the foundation for growth and development, and that’s good.

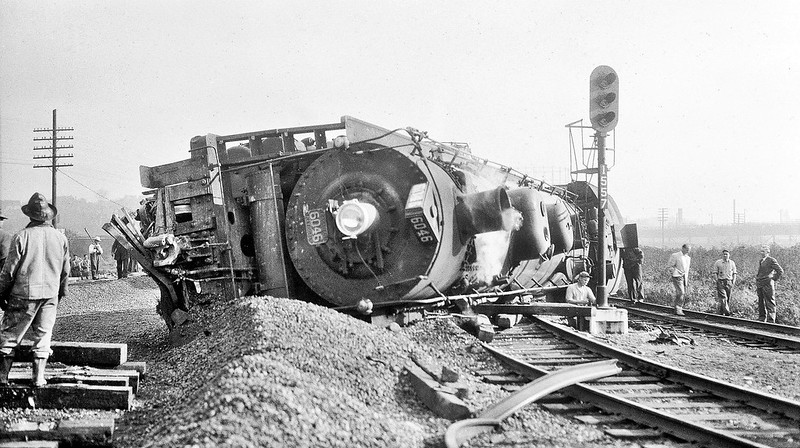

Learning can look like failure to the untrained eye. The prototype blew up – FAILURE. We thought the prototype would survive the test, but it didn’t. We ran a good test, learned the weakest element, and we’re improving it now – LEARNING. In both cases, the prototype is a complete wreck, but in the FAILURE scenario, the team is afraid to talk about it, and in the LEARNING scenario they brag. In the LEARNING scenario, each team member stands two inches taller.

Learning yes; failure no.

The transition from failure to learning starts with a question: What did you learn? It’s a magic question that helps the team see the progress instead of the shattered remains. It helps them see that their hard work has made them smarter. After several what-did-you-learns, the team will start to see what they learned. Without your prompts, they’ll know what they learned. Then, they’ll design their work around their desired learning. Then they’ll define formal learning objectives (LOs). Then they’ll figure out how to improve their learning rate. And then they’re off to the races.

You don’t break things for the sake of breaking them. You break things so you can learn.

Learning yes; failure no. Because language matters.

Image credit — mining camper

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski