Archive for October, 2024

It’s not the work, it’s the people.

I used to think the work was most important. Now I think it’s the people you work with.

I used to think the work was most important. Now I think it’s the people you work with.

Hard work is hard, but not when you share it with people you care about.

Struggle is tolerable when you’re elbow-to-elbow with people you trust.

Fear is manageable when you have faith in your crew.

You’re happy to carry an extra load when your friend needs the help.

And your friend is happy to do the same for you.

When you’ve been through the wringer a teammate, they grow into more than a teammate.

If you smile at work, it’s likely because of the people you work with.

And when you’re sad at work, it’s also likely because of to the people.

When you care about each other, things get easier, even when they’re not easy.

Stop what you’re doing and look at the people around you.

What do you see?

Who has helped you? Who has asked for help?

Who has confided in you? To whom have you confided?

Who believes in you? In whom do you believe?

Who are you happy to see? Who are you not?

Who will you miss when they’re gone?

For the most important people, take a minute and write down your shared experiences and what they mean to you.

What would it mean to them if you shared your thoughts and feelings?

Why not take a minute and find out?

Wouldn’t work be more energizing and fun?

If you agree, why not do it? What’s in the way? What’s stopping you?

Why not push through the discomfort and take things to the next level?

Image credit — HLI-Photography

When I’m Asked To Take On New Work

Here are the questions I ask myself when I’m asked to take on new work….

Here are the questions I ask myself when I’m asked to take on new work….

Do I know what the work is all about?

Is it well-defined?

Would it make a big difference if the work is completed successfully?

Would it make a big difference if it’s not?

Is it clear how to judge if the work is completed successfully?

Is the work important and how do I know?

Is it urgent? (The previous question is far more important to me.)

Is there more important work?

Who would benefit from the work and how do I feel about it?

Would I benefit and how do I feel about it?

Am I uniquely qualified or can others do the work?

Am I interested in the work?

Would I grow from the work?

Who would I work for?

Who would I work with?

Would my career progress?

Would I get a raise?

Would I spend more time with my family?

Would I spend more time in meetings?

Would I travel more?

What does my Trust Network think?

Would I have fun? (I think this is a powerful question.)

These aren’t the questions you should ask yourself, but I hope the list helps you develop your own.

Image credit — broombesoom

Swimming In New Soup

You know the space is new when you don’t have the right words to describe the phenomenon.

You know the space is new when you don’t have the right words to describe the phenomenon.

When there are two opposite sequences of events and you think both are right, you know the space is new.

You know you’re thinking about new things when the harder you try to figure it out the less you know.

You know the space is outside your experience but within your knowledge when you know what to do but you don’t know why.

When you can see the concept in your head but can’t drag it to the whiteboard, you’re swimming in new soup.

When you come back from a walk with a solution to a problem you haven’t yet met, you’re circling new space.

And it’s the same when know what should be but it isn’t – circling new space.

When your old tricks are irrelevant, you’re digging in a new sandbox.

When you come up with a new trick but the audience doesn’t care – new space.

When you know how an experiment will turn out and it turns out you ran an irrational experiment – new space.

When everyone disagrees, the disagreement is a surrogate for the new space.

It’s vital to recognize when you’re swimming in a new space. There is design freedom, new solutions to new problems, growth potential, learning, and excitement. There’s acknowledgment that the old ways won’t cut it. There’s permission to try.

And it’s vital to recognize when you’re squatting in an old space because there’s an acknowledgment that the old ways haven’t cut it. And there’s permission to wander toward a new space.

Image credit — Tambaco The Jaguar

If you want to make a difference, change the design.

Why do factories have 50-ton cranes? Because the parts are heavy and the fully assembled product is heavier. Why is the Boeing assembly facility so large? Because 747s are large. Why does a refrigerator plant have a huge room to accumulate a massive number of refrigerators that fail final test? Because refrigerators are big, because volumes are large, and a high fraction fail final test. Why do factories look as they do? Because the design demands it.

Why do factories have 50-ton cranes? Because the parts are heavy and the fully assembled product is heavier. Why is the Boeing assembly facility so large? Because 747s are large. Why does a refrigerator plant have a huge room to accumulate a massive number of refrigerators that fail final test? Because refrigerators are big, because volumes are large, and a high fraction fail final test. Why do factories look as they do? Because the design demands it.

Why are parts machined? Because the materials, geometries, tolerances, volumes, and cost requirements demand it. Why are parts injection molded? Because the materials, geometries, tolerances, volumes, and cost requirements demand it. Why are parts 3D printed? For prototypes, because the design can tolerate the class of materials that can be printed and can withstand the stresses and temperature of the application for a short time, the geometries are printable, and the parts are needed quickly. For production parts, it’s because the functionality cannot be achieved with a lower-cost process, the geometries cannot be machined or molded, and the customer is willing to pay for the high cost of 3D printing. Why are parts made as they are? Because the design demands it.

Why are parts joined with fasteners? It’s because the engineering drawings define the holes in the parts where the fasteners will reside and the fasteners are called out on the Bills Of Material (BOM). The parts cannot be welded or glued because they’re designed to use fasteners. And the parts cannot be consolidated because they’re designed as separate parts. Why are parts held together with fasteners? Because the design demands it.

If you want to reduce the cost of the factory, change the design so it does not demand the use of 50-ton cranes. If you want to get by with a smaller factory, change the design so it can be built in a smaller factory. If you want to eliminate the need for a large space to store refrigerators that fail final test, change the design so they pass. Yes, these changes are significant. But so are the savings. Yes, a smaller airplane carries fewer people, but it can also better serve a different set of customer needs. And, yes, to radically reduce the weight of a product will require new materials and a new design approach. If you want to reduce the cost of your factory, change the design.

If you want to reduce the cost of the machined parts, change the geometry to reduce cycle time and change to a lower-cost material. Or, change the design to enable near-net forging with some finish machining. If you want to reduce the cost of the injection molded parts, change the geometry to reduce cycle time and change the design to use a lower-cost material. If you want to reduce the cost of the 3D printed parts, change the design to reduce the material content and change the design and use lower-cost material. (But I think it’s better to improve function to support a higher price.) If you want to reduce the cost of your parts, change the design to make possible the use of lower-cost processes and materials.

If you want to reduce the material cost of your product, change the design to eliminate parts with Design for Assembly (DFA). What is the cost of a part that is designed out of the product? Zero. Is it possible to wrongly assemble a part that was designed out? No. Can a part that’s designed out be lost or arrive late? No and no. What’s the inventory cost of a part that’s been designed out? Zero. If you design out the parts is your supply chain more complicated? No, it’s simpler. And for those parts that remain use Design for Manufacturing (DFM) to work with your suppliers to reduce the cost of making the parts and preserve your suppliers’ profit margins.

If you want to sell more, change the design so it works better and solves more problems for your customers. And if you want to make more money, change the design so it costs less to make.

Resurrecting Manufacturing Through Product Simplification

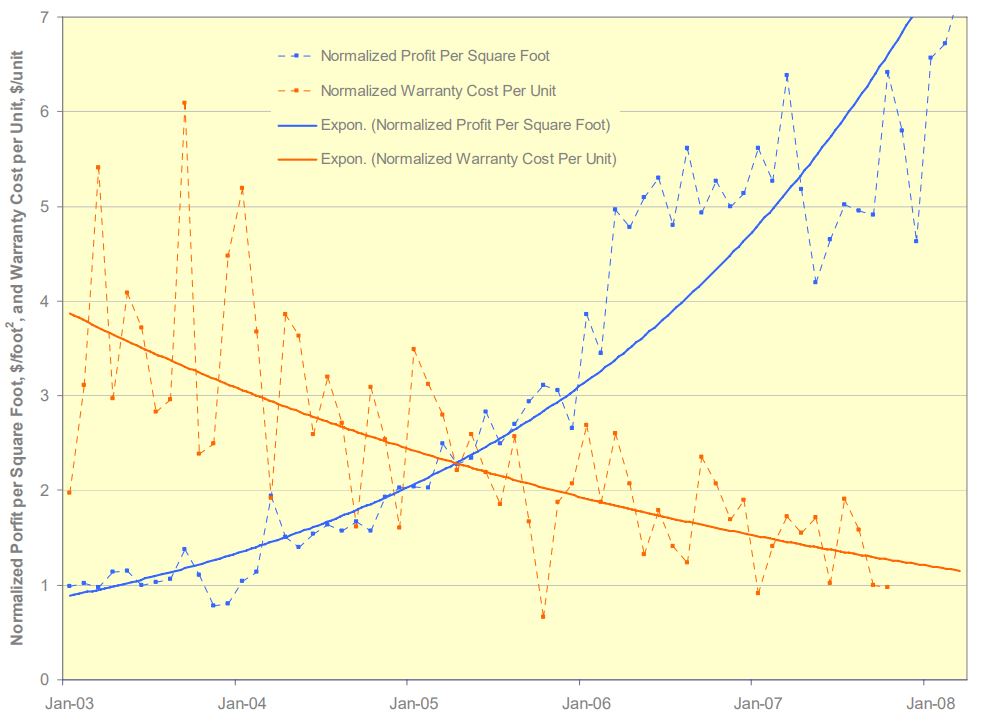

Product simplification can radically improve profits and radically improve product robustness. Here’s a graph of profit per square foot ($/ft^2) which improved by a factor of seven and warranty cost per unit ($/unit), a measure of product robustness), which improved by a factor of four. The improvements are measured against the baseline data of the legacy product which was replaced by the simplified product. Design for Assembly (DFA) was used to simplify the product and Robust Design methods were used to reduce warranty cost per unit.

I will go on record that everyone will notice when profit per square foot increases by a factor of seven.

And I will also go on record that no one will believe you when you predict product simplification will radically improve profit per square foot.

And I will go on record that when warranty cost per unit is radically reduced, customers will notice. Simply put, the product doesn’t break and your customers love it.

But here’s the rub. The graph shows data over five years, which is a long time. And if the product development takes two years, that makes seven long years. And in today’s world, seven years is at least four too many. But take another look at the graph. Profit per square foot doubled in the first two years after launch. Two years isn’t too long to double profit per square foot. I don’t know of a faster way, More strongly, I don’t know of another way to get it done, regardless of the timeline.

I think your company would love to double the profit per square foot of its assembly area. And I’ve shown you the data that proves it’s possible. So, what’s in the way of giving it a try?

For the details about the work, here’s a link – Systematic DFMA Deployment, It Could Resurrect US Manufacturing.

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski