Archive for September, 2021

Good Questions

This seems like a repeat of the last time we set a project launch date without regard for the work content. Do you see it that way?

This person certainly looks the part and went to the right school, but they have not done this work before. Why do you think we should hire them even though they don’t have the experience?

The last time we ran a project like this it took two years to complete. Why do you think this one will take six months?

If it didn’t work last time, why do you think it will work this time?

Why do you think we can do twice the work we did last year while reducing our headcount?

The work content, timeline, and budget are intimately linked. Why do you think it’s possible to increase the work content, pull in the timeline, and reduce the budget?

Seven out of thirteen people have left the team. How many people have to leave before you think we have a problem?

Yes, we’ve had great success with that approach over the last decade, but our most recent effort demonstrated that our returns are diminishing. Why do you want to do that again?

If you think it’s such a good idea, why don’t you do it?

Why do you think it’s okay to add another project when we’re behind on all our existing projects?

Customers are buying the competitive technology. Why don’t you believe that they’re now better than we are?

This work is critical to our success, yet we don’t have the skills sets, capacity, or budget to hire it out. Why are you telling us you will get it done?

This problem seems to fit squarely within your span of responsibility. Why do you expect other teams to fix it for you?

I know a resource gap of this magnitude seems unbelievable but is what the capacity model shows. Why don’t you believe the capacity model?

We have no one to do that work. Why do you think it’s okay to ask the team to sign up for something they can’t pull off?

Based on the survey results, the culture is declining. Why don’t you want to acknowledge that?

“I have a question” by The U.S. Army is licensed under CC BY 2.0

How to Decide if Your Problem is Worth Solving

How to decide if a problem is worth solving?

How to decide if a problem is worth solving?

If it’s a new problem, try to solve it.

If it’s a problem that’s already been solved, it can’t be a new problem. Let someone else re-solve it.

If a new problem is big, solve it in a small way. If that doesn’t work, try to solve it in a smaller way.

If there’s a consensus that the problem is worth solving, don’t bother. Nothing great comes from consensus.

If the Status Quo tells you not to solve it, you’ve hit paydirt!

If when you tell people about solving the problem they laugh, you’re onto something.

If solving the problem threatens the experts, double down.

If solving the problem obsoletes your most valuable product, solve it before your competition does.

If solving the problem blows up your value proposition, light the match.

If solving the problem replaces your product with a service, that’s a recipe for recurring revenue.

If solving the problem frees up a factory, well, now you have a free factory to make other things.

If solving the problem makes others look bad, that’s why they’re trying to block you from solving it.

If you want to know if you’re doing it right, make a list of the new problems you’ve tried to solve.

If your list is short, make it longer.

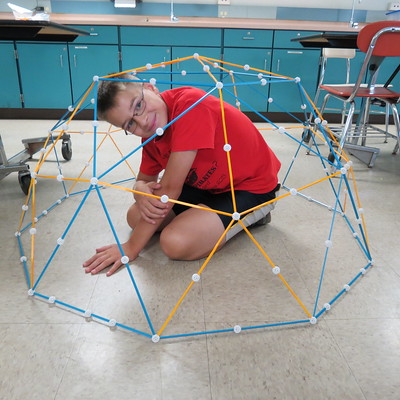

“CERDEC Math and Science Summer Camp, 2013” by CCDC_C5ISR is licensed under CC BY 2.0

If nine out of ten projects projects fail, you’re doing it wrong.

For work that has not been done before, there’s no right answer. The only wrong answer is to say “no” to trying something new. Sure, it might not work. But, the only way to guarantee it won’t work is to say no to trying.

For work that has not been done before, there’s no right answer. The only wrong answer is to say “no” to trying something new. Sure, it might not work. But, the only way to guarantee it won’t work is to say no to trying.

If innovation projects fail nine out of ten times, you can increase the number of projects you try or you can get better at choosing the projects to say no to. I suggest you say learn to say yes to the one in ten projects that will be successful.

If you believe that nine out of ten innovation projects will fail, you shouldn’t do innovation for a living. Even if true, you can’t have a happy life going to work every day with a ninety percent chance of failure. That failure rate is simply not sustainable. In baseball, the very best hitters of all time were unsuccessful sixty percent of the time, yet, even they focused on the forty percent of the time they got it right. Innovation should be like that.

If you’ve failed on ninety percent of the projects you’ve worked on, you’ve probably been run out of town at least several times. No one can fail ninety percent of the time and hold onto their job.

If you’ve failed ninety percent of the time, you’re doing it wrong.

If you’ve failed ninety percent of the time, you’ve likely tried to solve the wrong problems. If so, it’s time to learn how to solve the right problems. The right problems have two important attributes: 1) People will pay you if they are solved. 2) They’re solvable. I think we know a lot about the first attribute and far too little about the second. The problem with solvability is that there’s no partial credit, meaning, if a problem is almost solvable, it’s not solvable. And here’s the troubling part: if a problem is almost solved, you get none of the money. I suggest you tattoo that one on your arm.

As a subject matter expert, you know what could work and what won’t. And if you don’t think you can tell the difference, you’re not a subject matter expert.

Here’s a rule to live by: Don’t work on projects that you know won’t work.

Here’s a corollary: If your boss asks you to work on something that won’t work, run.

If you don’t think it will work, you’re right, even if you’re not.

If it might work, that’s about right. If it will work, let someone else do it. If it won’t work, run.

If you’ve got no reason to believe it will work, it won’t.

If you can’t imagine it will work, it won’t.

If someone else says it won’t work, it might.

If someone else tries to convince you it won’t work, they may have selfish reasons to think that way.

It doesn’t matter if others think it won’t work. It matters what you think.

So, what do you think?

If you someone asks you to believe something you don’t, what will you do?

If you try to fake it until you make it, the Universe will make you pay.

If you think you can outsmart or outlast the Universe, you can’t.

If you have a bad feeling about a project, it’s a bad project.

If others tell you that it’s a bad project, it may be a good one.

Only you can decide if a project is worth doing.

It’s time for you to decide.

“Good example of Crossfit Weight lifting – In Crossfit Always lift until you reach the point of Failure or you tear something” by CrossfitPaleoDietFitnessClasses is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Run toward the action!

Companies have control over one thing: how to allocate their resources. Companies allocate resources by deciding which projects to start, accelerate, and stop; whom to allocate to the projects; how to go about the projects; and whom to hire, invest in, and fire. That’s it.

Companies have control over one thing: how to allocate their resources. Companies allocate resources by deciding which projects to start, accelerate, and stop; whom to allocate to the projects; how to go about the projects; and whom to hire, invest in, and fire. That’s it.

Taking a broad view of project selection to include starting, accelerating, and stopping projects, as a leader, what is your role in project selection, or, at a grander scale, initiative selection? When was the last time you initiated a disruptive yet heretical new project from scratch? When was the last time you advocated for incremental funding to accelerate a floundering yet revolutionary project? When was the last time you stopped a tired project that should have been put to rest last year? And because the projects are the only thing that generates revenue for your company, how do you feel about all that?

Without your active advocacy and direct involvement, it’s likely the disruptive project won’t see the light of day. Without you to listen to the complaints of heresy and actively disregard them, the organization will block the much-needed disruption. Without your brazen zeal, it’s likely the insufficiently-funded project won’t revolutionize anything. Without you to put your reputation on the line and decree that it’s time for a revolution, the organization will starve the project and the revolution will wither. Without your critical eye and thought-provoking questions, it’s likely the tired project will limp along for another year and suck up the much-needed resources to fund the disruptions, revolutions, and heresy.

Now, I ask you again. How do you feel about your (in)active (un)involvement with starting projects that should be started, accelerating projects that should be accelerated, and stopping projects that should be stopped?

And with regard to project staffing, when was the last time you stepped in and replaced a project manager who was over their head? Or, when was the last time you set up a recurring meeting with a project manager whose project was in trouble? Or, more significantly, when was the last time you cleared your schedule and ran toward the smoke of an important project on fire? Without your involvement, the over-their-head project manager will drown. Without your investment in a weekly meeting, the troubled project will spiral into the ground. Without your active involvement in the smoldering project, it will flame out.

As a leader, do you have your fingers on the pulse of the most important projects? Do you have the knowledge, skills, and abilities to know which projects need help? And do you have the chops to step in and do what must be done? And how do you feel about all that?

As a leader, do you know enough about the work to provide guidance on a major course change? Do you know enough to advise the project team on a novel approach? Do you have the gumption to push back on the project team when they don’t want to listen to you? As a leader, how do you feel about that?

As a leader, you probably have direct involvement in important hiring and firing decisions. And that’s good. But, as a leader, how much of your time do you spend developing young talent? How many hours per week do you talk to them about the details of their projects and deliverables? How many hours per week do you devote to refactoring troubled projects with the young project managers? And how do you feel about that?

If you want to grow revenue, shape the projects so they generate more revenue. If you want to grow new businesses, advocate for projects that create new businesses. If you need a revolution, start revolutionary projects and protect them. And if you want to accelerate the flywheel, help your best project managers elevate their game.

“Speeding Pinscher” by PincasPhoto is licensed under CC BY 2.0

A Leading Indicator of Personal Growth — Fear

When was the last time you did something that scared you? And a more important follow-on question: How did you push through your fear and turn it into action?

When was the last time you did something that scared you? And a more important follow-on question: How did you push through your fear and turn it into action?

Fear is real. Our bodies make it, but it’s real. And the feelings we create around fear are real, and so are the inhibitions we wrap around those feelings. But because we have the authority to make the fear, create the feelings, and wrap the inhibitions, we also have the authority to unmake, un-create, and unwrap.

Fear can feel strong. Whether it’s tightness in the gut, coldness in the chest, or lushness in the face, the physical manifestations in the body are recognizable and powerful. The sensations around fear are strong enough to stop us in our tracks. And in the wild of a bygone time, that was fear’s job – to stop us from making a mistake that would kill us. And though we no longer venture into the wild, fear responds to family dynamics, social situations, interactions at work, as if we still live in the wild.

To dampen the impact of our bodies’ fear response, the first step is to learn to recognize the physical sensations of fear for what they are – sensations we make when new situations arise. To do that, feel the sensations, acknowledge your body made them, and look for the novelty, or divergence from our expectations, that the sensations stand for. In that way, you can move from paralysis to analysis. You can move from fear as a blocker to fear as a leading indicator of personal growth.

Fear is powerful, and it knows how to create bodily sensations that scare us. But, that’s the chink in the armor that fear doesn’t want us to know. Fear is afraid to be called by name, so it generates these scary sensations so it can go on controlling our lives as it sees fit. So, next time you feel the sensations of fear in your body, welcome fear warmly and call it by name. Say something like, “Hello Fear. Thank you for visiting with me. I’d like to get to know you better. Can you stay for a coffee?”

You might find that Fear will engage in a discussion with you and apologize for causing you trouble. Fear may confess that it doesn’t like how it treats you and acknowledge that it doesn’t know how to change its ways. Or, it may become afraid and squirt more fear sensations into your body. If that happens, tell Fear that you understand it’s just doing what it evolved to do, and repeat your offer to sit with it and learn more about its ways.

The objective of calling Fear by name is to give you a process to feel and validate the sensations and then calm yourself by looking deeply at the novelty of the situation. By looking squarely into Fear’s eyes, it will slowly evaporate to reveal the nugget of novelty it was cloaking. And with the novelty in your sights, you can look deeply at this new situation (or context or interpersonal dynamic) and understand it for what it is. Without Fear’s distracting sensations, you will be pleasantly surprised with your ability to see the situation for what it is and take skillful action.

So, when Fear comes, feel the sensations. Don’t push them away. Instead, call Fear by name. Invite Fear to tell its story, and get to know it. You may find that accepting Fear for what it is can help you grow your relationship with Fear into a partnership where you help each other grow.

“tractor pull 02 – Arnegard ND – 2013-07-04” by Tim Evanson is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski