Archive for May, 2018

A Little Uninterrupted Work Goes a Long Way

If your day doesn’t start with a list of things you want to get done, there’s little chance you’ll get them done. What if you spent thirty minutes to define what you want to get done and then spent an hour getting them done? In ninety minutes you’ll have made a significant dent in the most important work. It doesn’t sound like a big deal, but it’s bigger than big. Question: How often do you work for thirty minutes without interruptions?

If your day doesn’t start with a list of things you want to get done, there’s little chance you’ll get them done. What if you spent thirty minutes to define what you want to get done and then spent an hour getting them done? In ninety minutes you’ll have made a significant dent in the most important work. It doesn’t sound like a big deal, but it’s bigger than big. Question: How often do you work for thirty minutes without interruptions?

Switching costs are high, but we don’t behave that way. Once interrupted, what if it takes ten minutes to get back into the groove? What if it takes fifteen minutes? What if you’re interrupted every ten or fifteen minutes? Question: What if the minimum time block to do real thinking is thirty minutes of uninterrupted time?

Let’s assume for your average week you carve out sixty minutes of uninterrupted time each day to do meaningful work, then, doing as I propose – spending thirty minutes planning and sixty minutes doing something meaningful every day – increases your meaningful work by 50%. Not bad. And if for your average week you currently spend thirty contiguous minutes each day doing deep work, the proposed ninety-minute arrangement increases your meaningful work by 200%. A big deal. And if you only work for thirty minutes three out of five days, the ninety-minute arrangement increases your meaningful work by 400%. A night and day difference.

Question: How many times per week do you spend thirty minutes of uninterrupted time working on the most important things? How would things change if every day you spent thirty minutes planning and sixty minutes doing the most important work?

Great idea, but with today’s business culture there’s no way to block out ninety minutes of uninterrupted time. To that I say, before going to work, plan for thirty minutes at home. And set up a sixty-minute recurring meeting with yourself first thing every morning and do sixty minutes of uninterrupted work. And if you can’t sit at your desk without being interrupted, hold the sixty-minute meeting with yourself in a location where you won’t be interrupted. And, to make up for the thirty minutes you spent planning at home, leave thirty minutes early.

No way. Can’t do it. Won’t work.

It will work. Here’s why. Over the course of a month, you’ll have done at least 50% more real work than everyone else. And, because your work time is uninterrupted, the quality of your work will be better than everyone else’s. And, because you spend time planning, you will work on the most important things. More deep work, higher quality working conditions, and regular planning. You can’t beat that, even if it’s only sixty to ninety minutes per day.

The math works because in our normal working mode, we don’t spend much time working in an uninterrupted way. Do the math for yourself. Sum the number of minutes per week you spend working at least thirty minutes at time. And whatever the number, figure out a way to increase the minutes by 50%. A small number of minutes will make a big difference.

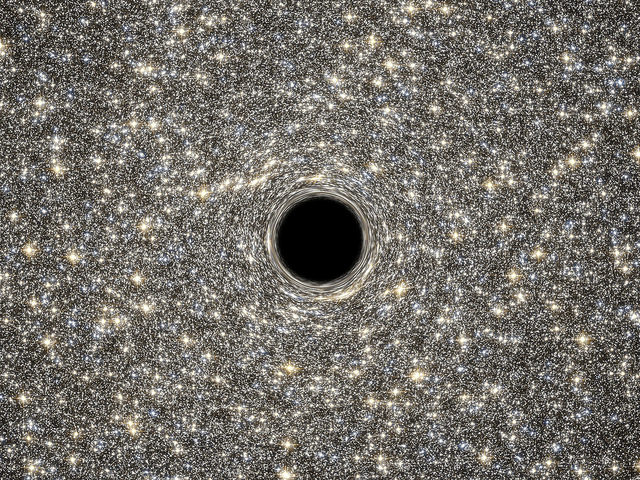

Image credit – NASA Goddard Space Flight Center

Testing the Business Model

Sometimes we get caught up in the details when we should be working on the foundation. Here’s a rule: If the underlying foundation is not secure, don’t bother working on anything else.

Sometimes we get caught up in the details when we should be working on the foundation. Here’s a rule: If the underlying foundation is not secure, don’t bother working on anything else.

If you’re working on a couple new technologies, but the overall business model won’t be profitable, don’t work on the new technologies. Instead, figure out a business model that is profitable, then do what it takes (technology, simplification, process improvement) to make it happen. But, often, that’s not what we do.

Often, we put the cart before the horse. We create projects to make prototypes that demonstrate a new technology, but the whole business premise is built on quicksand. There’s a reason why foundations are made from concrete and not quicksand. It’s because you can build on top of a base made of concrete. It supports the load. It doesn’t crack, nor does it fall apart. Think Pyramid of Giza.

Because foundations are big and expensive they can be difficult and expensive to test. For example, if an innovation is based on a new foundation, say, a new business model, building a physical prototype of the new business model is too expensive and the testing will not happen. And what usually happens is the foundation goes untested, the higher level technology work is done, the commercialization work is completed and the business model fails because it wasn’t solid.

But you don’t have to build a full-scale prototype of the Pyramid of Giza to test if a pyramid will stand the test of time. You can build a small one and test it, or you can run an analysis of some sort to understand if the pyramid will support the weight. But what if you want to test a new business model, a business model that has never been done before, using new products and services that have never seen the light of day? What do you do? In this case, it doesn’t make sense to make even a scale model. But it does make sense to create a one page sales tool that describes the whole thing and it does make sense to show it to potential customers and ask them what they think about it.

The open question with all new things is – will customers like it enough to buy it. And, it’s no different with the business model. Instead of creating a new website, staffing up, creating new technologies and products, create a one-page sales tool that describes the new elements and show it to potential customers. Distill the value proposition into language people can understand, describe the novelty that fuels the value, capture it on one page, show it to customers, and listen.

And don’t build a single, one-page sales tool, build two or three versions. And then, ask customers what they think. Odds are, they’ll ask you questions you didn’t think they’d ask. Odds are, they’ll see it differently than you do. And, odds are, you’ll have to incorporate their feedback into an improved version of the business model. The bad new is you didn’t get it right. The good news is you didn’t have to staff up and build the whole business model, create the technologies and launch the products. And more good news – you can quickly modify the one-page sales tool and go back to the customers and ask them what they think. And you can do this quickly and inexpensively.

Don’t develop the technology until you know the underlying business model will be profitable. Don’t staff up until you know if the business model holds water. Don’t launch the new products until you verify customers will buy what you want to sell.

Creating a new business model from scratch is an expensive proposition. Don’t build it until you invest in validating it’s worth building.

The worst way to validate a business model is by building it.

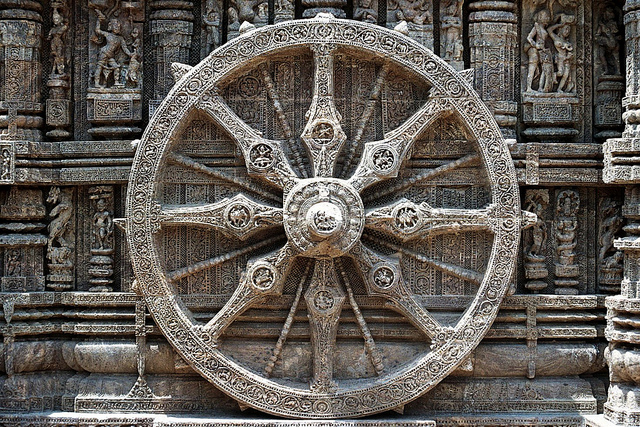

Image credit – David Stanley

Make life easy for your customers.

Companies that have products want to improve them year-on-year. This year’s must be better than last year’s. For selfish reasons, we like to improve cost, speed and quality. Cost reduction drops profit directly to the bottom line. Increased speed reduces overhead (less labor per unit) and increases floor space productivity (more through the factory). Improved quality reduces costs. And for our customers, we like to improve their productivity by helping them do more value-added work with fewer resources. More with less! But there’s a problem – every year it gets more difficult to improve on last year, especially with our narrowly-defined view of what customers value.

Companies that have products want to improve them year-on-year. This year’s must be better than last year’s. For selfish reasons, we like to improve cost, speed and quality. Cost reduction drops profit directly to the bottom line. Increased speed reduces overhead (less labor per unit) and increases floor space productivity (more through the factory). Improved quality reduces costs. And for our customers, we like to improve their productivity by helping them do more value-added work with fewer resources. More with less! But there’s a problem – every year it gets more difficult to improve on last year, especially with our narrowly-defined view of what customers value.

And some companies talk about creating the next generation business model, though no one’s quite sure of what the business model actually is and what makes for a better one.

To break out of our narrow view of “better” and to avoid endless arguments over business models, I suggest an approach based on a simple mantra – Make It Easy.

Make it easy for the customer to _____________.

And take a broad view of what customers actually do. Here are some ideas:

Make it easy to find you. If they can’t find you, they can’t buy from you.

Make it easy to understand what you do and why you do it. Give them a reason to buy.

Make it easy to choose the right solution. No one likes buying the wrong thing.

Make it easy to pay. If they need a loan, why not find one for them?

Make it easy to receive. Think undamaged, recyclable packaging, easy to get off the truck.

Make it easy to install. Don’t think user manuals, think self-installation.

Make it easy to verify it’s ready to go. No screens, no menus. One green light.

Make it easy to deliver the value-added benefit. We over-focus here and can benefit by thinking more broadly. Make it easy to set up, easy to verify the setup, easy to know how to use it, easy change over to the next job.

Make it easy to know the utilization. The product knows when it’s being used, why not give it the authority to automatically tell people how much free time it has?

Make it easy to maintain. When the fastest machine in the world is down for the count, it becomes tied for the slowest machine in the world. Make it easy to know what needs be replaced and when, make it easy to know how to replace it, make it easy to order the replacement parts, make it easy to verify the work was done correctly, make it easy to notify that the work was done correctly, and make it easy to reset the timers.

Make it easy to troubleshoot. Even the best maintenance programs don’t eliminate all the problems. Think auto-diagnosis. Then, like with maintenance, all the follow-on work should be easy.

Make it easy to improve. As the product is used, it learns. It recognizes who is using it, remembers how they like it to behave, then assumes the desired persona.

Though this list is not exhaustive, it provides some food for thought. Yes, most of the list is not traditionally considered value-added activities. But, customers DO value improvements in these areas because these are the jobs they must do. If your competition is focused narrowly on productivity, why not differentiate by making it easy in a more broader sense? When you do, they’ll buy more.

And don’t argue about your business model. Instead, choose important jobs to be done and make them easier for the customer. In that way, how you prioritize your work defines your business model. Think of the business model as a result.

And for a deeper dive on how to make it easy, here’s one of my favorite posts. The takeaway – Don’t push people toward an objective. Instead, eliminate what’s in the way.

Image credit – Hernán Piñera

The Slow No

When there’s too much to do and too few to do it, the natural state of the system is fuller than full. And in today’s world we run all our systems this way, including our people systems.

When there’s too much to do and too few to do it, the natural state of the system is fuller than full. And in today’s world we run all our systems this way, including our people systems.

A funny thing happens when people’s plates are full – when a new task is added an existing one hits the floor. This isn’t negligence, it’s not the result of a bad attitude and it’s not about being a team player. This is an inherent property of full plates – they cannot support a new task without another sliding off. And drinking glasses have this same interesting property – when full, adding more water just gets the floor wet.

But for some reason we think people are different. We think we can add tasks without asking about free capacity and still expect the tasks to get done. What’s even more strange – when our people tell us they cannot get the work done because they already have too much, we don’t behave like we believe them. We say things like “Can you do more things in parallel?” and “Projects have natural slow phases, maybe you can do this new project during the slow times.” Let’s be clear with each other – we’re all overloaded, there are no slow times.

For a long time now, we’ve told people we don’t want to hear no. And now, they no longer tell us. They still know they can’t get the work done, but they know not to use the word “no.” And that’s why the Slow No was invented.

The Slow No is when we put a new project on the three year road map knowing full-well we’ll never get to it. It’s not a no right now, it’s a no three years from now. It’s elegant in its simplicity. We’ll put it on the list; we’ll put it in the queue; we’ll put it on the road map. The trick is to follow normal practices to avoid raising concerns or drawing attention. The key to the Slow No is to use our existing planning mechanisms in perfectly acceptable ways.

There’s a big downside to the Slow No – it helps us think we’ve got things under control when we don’t. We see a full hopper of ideas and think our future products will have sizzle. We see a full road map and think we’re going to have a huge competitive advantage over our competitors. In both situations, we feel good and in both situations, we shouldn’t. And that’s the problem. The Slow No helps us see things as we want them and blocks us from seeing them as they are.

The Slow No is bad for business, and we should do everything we can to get rid of it. But, it’s engrained behavior and will be with us for the near future. We need some tools to battle the dark art of the Slow No.

The Slow No gives too much value to projects that are on the list but inactive. We’ve got to elevate the importance of active, fully-staffed projects and devalue all inactive projects. Think – no partial credit. If a project is active and fully-staffed, it gets full credit. If it’s inactive (on a list, in the queue, or on the road map) it gets zero credit. None. As a project, it does not exist.

To see things as they are, make a list of the active, fully-staffed projects. Look at the list and feel what you feel, but these are the only projects that matter. And for the road map, don’t bother with it. Instead, think about how to finish the projects you have. And when you finish one, start a new one.

The most difficult element of the approach is the valuation of active but partially-staffed projects. To break the vice grip of the Slow No, think no partial credit. The project is either fully-staffed or it isn’t And if it’s not fully-staffed, give the project zero value. None. I know this sounds outlandish, but the partially-staffed project is the slippery slope that gives the Slow No its power.

For every fully-staffed project on your list, define the next project you’ll start once the current one is finished. Three active projects, three next projects. That’s it. If you feel the need to create a road map, go for it. Then, for each active project, use the road map to choose the next projects. Again, three active projects, three next projects. And, once the next projects are selected, there’s no need to look at the road map until the next projects are almost complete.

The only projects that truly matter are the ones you are working on.

Image credit – DaPuglet

Being Right in the Right Way

When something doesn’t feel right, respect your intuition. Even when you don’t know why it doesn’t feel right, respect your gut. When something doesn’t make sense, don’t judge yourself negatively. Rather, make the commitment to dig deeply until you hit the fundamentals. When a proposed approach violates something inside, don’t be afraid to say what you think is right. Or, be afraid and say it anyway. But right doesn’t mean your predictions will come true. Right means you thought about it, you understand things differently and you have a coherent rationale for thinking as you do. And right also means you don’t understand, but you want to. And right means something does not sit well with you and you don’t know why. And it means the right view is important to you.

When something doesn’t feel right, respect your intuition. Even when you don’t know why it doesn’t feel right, respect your gut. When something doesn’t make sense, don’t judge yourself negatively. Rather, make the commitment to dig deeply until you hit the fundamentals. When a proposed approach violates something inside, don’t be afraid to say what you think is right. Or, be afraid and say it anyway. But right doesn’t mean your predictions will come true. Right means you thought about it, you understand things differently and you have a coherent rationale for thinking as you do. And right also means you don’t understand, but you want to. And right means something does not sit well with you and you don’t know why. And it means the right view is important to you.

Right doesn’t mean correct. And right doesn’t mean something else is wrong. When you have right view, it doesn’t mean you see things exactly right. It means you’re going about things in a way that’s right for the situation. It means your approach feels right to the people involved. It means you’re going about things with the right intention.

Now, like with any new idea, you’re obligated to formalize what you think is right and explain it to your peers. But, to be clear, you’re not looking for permission, you’re writing it down to help you understand what you think. When you try to present your thoughts, you’ll learn what you know and what you don’t. You’ll learn which words work and which don’t. You’ll learn right speech.

And you’ll find the potholes. And that’s why you present to your peers. They’ll be critical of the idea and respectful of you. They’ll tell you the truth because they know it’s better to iron out the details early and often. As a group, you’ll support each other. As a group, you’ll take the right action.

When ideas are introduced that are different, the organization will feel stress. Everyone wants to do a good job, yet there’s no agreement on the right way. Even though there’s stress, no one wants to create harm and everyone wants to behave ethically. It’s important to demonstrate compassion to yourself and others. The stress is natural, but it’s also natural to go about your livelihood in the right way.

But when the stakes are high and there’s no consensus on how to move forward, it’s not easy to hold onto the right mental state. The stress can cause us to delude ourselves into thinking things aren’t going well. But, letting the disagreement go unaddressed is unskillful, as it will only fester. It’s far more skillful to respectfully debate and discuss the disagreement. In that way, everyone makes the right effort to work things out.

Over time, the pattern of behavior can transition to a natural openness where ideas are shared freely. This becomes easier when we drop the mental habit of categorizing things into buckets we like and buckets we don’t. And it helps to maintain awareness of how things really are so we can strip away our subjective options. In this case, mindfulness is the right way to go.

None of this is easy. Our minds are constantly distracted by competing demands, growing to-do lists and organizational complexities of the work. Without dedicated practice, our minds can get lost in a flurry of thoughts of our own creation. To make it work, we’ve got to maintain a heightened alertness to our mental state and that takes the right concentration.

There’s nothing new here, but this well-worn path has merit.

Image credit – saamiblog

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski