Archive for April, 2018

How to Choose the Best Idea

We have too many ideas, but too few great ones. We don’t need more ideas, we need a way to choose the best one or two ideas and run them to ground.

We have too many ideas, but too few great ones. We don’t need more ideas, we need a way to choose the best one or two ideas and run them to ground.

Before creating more ideas, make a list of the ones you already have. Put them in two boxes. In Box 1, list the ideas without a video of a functional prototype in action. In Box 2, list the ideas that have a video showing a functional prototype demonstrating the idea in action. For those ideas with a functional prototype and no video, put them in Box 1.

Next, throw away Box 1. If it’s not important enough to make a crude physical prototype and create a simple video, the idea isn’t worth a damn. If someone isn’t willing to carve out the time to make a physical prototype, there’s no emotional energy behind the idea and it should be left to die. And when people complain that it’s unfair to throw away all those good ideas in Box 1, tell them it’s unfair to spend valuable resources talking about ideas that aren’t worthy. And suggest, if they want to have a discussion about an idea, they should build a physical prototype and send you the video. Box 2, or bust.

Next, get the band together and watch the short videos in Box 2, and, as a group, put them in two boxes. In Box 3, put the videos without customers actively using the functional prototype. In Box 4, put the videos with customers actively using the functional prototype.

Next, throw way Box 3. If it’s not important enough to make a trip to an important customer and create a short video, the idea isn’t worth a damn. If you’re not willing to put yourself out there and take the idea to an important customer, the idea is all fizzle and no sizzle. Meaningful ideas take immense personal energy to run through the gauntlet, and without a video of a customer using the functional prototype, there’s not enough energy behind it. And when everyone argues that Box 3 ideas are worth pursuing, tell them to pursue a video showing a most important customer demonstrating the functional prototype.

Next, get the band back together to watch the Box 4 videos. Again, put the videos in two boxes. In Box 5 put the videos where the customer didn’t say what they liked and how they’d use it. In Box 6, put the videos where the customer enthusiastically said what they liked and how they’ll use it.

Next, throw away Box 5. If the customer doesn’t think enough about the prototype to tell you how they’ll use it, it’s because they don’t think much of the idea. And when the group says the customer is wrong or the customer doesn’t understand what the prototype is all about, suggest they create a video where a customer enthusiastically explains how they’d use it.

Next, get the band back in the room and watch the Box 6 videos. Put them in two boxes. In Box 7, put the videos that won’t radically grow the top line. In Box 8, put the videos that will radically grow the top line. Throw away Box 7.

For the videos in Box 8, rank them by the amount of top line growth they will create. Put all the videos back into Box 8, except the video that will create the most top line growth. Do NOT throw away Box 8.

The video in your hand IS your company’s best idea. Immediately charter a project to commercialize the idea. Staff it fully. Add resources until adding resources doesn’t no longer pulls in the launch. Only after the project is fully staffed do you put your hand back into Box 8 to select the next best idea.

Continually evaluate Boxes 1 through 8. Continually throw out the boxes without the right videos. Continually choose the best idea from Box 8. And continually staff the projects fully, or don’t start them.

Image credit – joiseyshowaa

Everyday Leadership

What if your primary role every day was to put other people in a position to succeed? What would you start doing? What would you stop doing? Could you be happy if they got the credit and you didn’t? Could you feel good about their success or would you feel angry because they were acknowledged for their success? What would happen if you ran the experiment?

What if your primary role every day was to put other people in a position to succeed? What would you start doing? What would you stop doing? Could you be happy if they got the credit and you didn’t? Could you feel good about their success or would you feel angry because they were acknowledged for their success? What would happen if you ran the experiment?

What if each day you had to give ten compliments? Could you notice ten things worthy of compliment? Could you pay enough attention? Would it be difficult to give the compliments? Would it be easy? Would it scare you? Would you feel silly or happy? Who would be the first person you’d compliment? Who is the last person you’d compliment? How would they feel? What could it hurt to try it for a week?

What if each day you had to ask five people if you can help them? Could you do it even for one day? Could you ask in a way the preserves their self-worth? Could you ask in a sincere way? How do you think they would feel if you asked them? How would you feel if they said yes? How about if they said no? Would the experiment be valuable? Would it be costly? What’s in the way of trying it for a day? How do you feel about what’s in the way?

What if you made a mistake and you had to apologize to five people? Could you do it? Would you do it? Could you say “I’m sorry. I won’t do it again. How can I make it up to you?” and nothing else? Could you look them in the eye and apologize sincerely? If your apology was sincere, how would they feel? And how would you feel? Next time you make a mistake, why not try to apologize like you mean it? What could it hurt? Why not try?

What if every day you had to thank five people? Could you find five things to be thankful for? Would you make the effort to deliver the thanks face-to-face? Could you do it for two days? Could you do it for a week? How would you feel if you actually did it for a week? How would the people around you feel? How do you feel about trying it?

What if every day you tried to be a leader?

Image credit – Pedro Ribeiro Simões

For top line growth, think no-to-yes.

Bottom line growth is good, but top line growth is better. But if you want to grow the bottom line, ignore labor costs and reduce material costs. Labor cost is only 5-10% of product cost. Stop chasing it, and, instead, teach your design community to simplify the product so it uses fewer parts and design out the highest cost elements.

Bottom line growth is good, but top line growth is better. But if you want to grow the bottom line, ignore labor costs and reduce material costs. Labor cost is only 5-10% of product cost. Stop chasing it, and, instead, teach your design community to simplify the product so it uses fewer parts and design out the highest cost elements.

Where the factory creates bottom line growth, top line growth is generated in the market/customer domain. The best way I know to grow the top line is to broaden the applicability of your products and services. But, before you can broaden applicability, you’ve got to define applicability as it is. Define the limits of what your product can do – how much it can lift, how fast it can run a calculation and where it can be used. And for your service, define who can use it, where it can be used and what elements without customer involvement. And with the limits defined, you know where top line growth won’t come from.

Radical top line growth comes only when your products and services can be used in new applications. Sure, you can train your sales force to sell more of what you already have, but that runs out of gas soon enough. But, real top line growth comes when your services serve new customers in new ways. By definition, if you’re not trying to make your product work in new ways, you’re not going to achieve meaningful top line growth. And by definition, if you’re not creating new functionality for your services, you might as well be focusing on bottom line growth.

If your product couldn’t do it and now it can, you’re doing it right. If your service couldn’t be used by people that speak Chinese and now it can, you’re on your way. If your product couldn’t be used in applications without electricity and now it can, you’re on to something. If your service couldn’t run on a smartphone and now it can, well, you get the idea.

For the acid test, think no-to-yes.

If your product can’t work in application A, you can’t sell it to people who do that work. If your service can’t be used by visually impaired people, you’re not delivering value to them and they won’t buy it. Turning can’t into can is a big deal. But you’ve got to define can’t before you can turn it into can. If you want top line growth, take the time to define the limits of applicability.

No-to-yes is powerful because it creates clarity. It’s easy to know when a project will create no-to-yes functionality and when it won’t. And that makes it easy to stop projects that don’t deliver no-to-yes value and start projects that do.

No-to-yes is the key element of a compete-with-no-one approach to business.

image credit – liebeslakritze

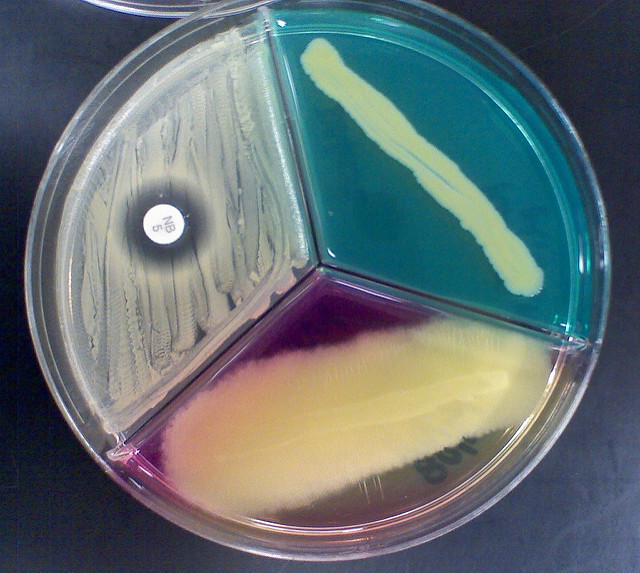

How to Avoid a Cliff

Much like living organisms continually evolve to secure their place in the future, technological systems can be thought to display similar evolutionary behavior. Viruses mutate so some of them can defeat the countermeasures of their host and live to fight another day. Technological systems, as an expression of a company’s desire to survive, evolve to defeat the competition and live to pay another dividend.

Much like living organisms continually evolve to secure their place in the future, technological systems can be thought to display similar evolutionary behavior. Viruses mutate so some of them can defeat the countermeasures of their host and live to fight another day. Technological systems, as an expression of a company’s desire to survive, evolve to defeat the competition and live to pay another dividend.

There are natural limits to evolutionary success in any single direction. When one trait is improved it pushes on the natural limits imposed by the environment. For example, a bacterium let loose in a friendly Petri dish will replicate until it eats all the food in the dish. Or, on a longer timescale, if the mass of a bird increases over generations when its food source is plentiful, the bird will get larger but will also get less agile. The predators who couldn’t catch the fast, little bird of old can easily catch and eat the sluggish heavyweight. In that way, there’s an edge condition created by the environmental Petri dishes and predators. And it’s the same with technological systems.

Companies and their technological systems evolve within their competitive environment by scanning the fitness landscape and deciding where to try to improve. The idea is to see preferential lines of improvement and create new technologies to take advantage of them. Like their smaller biological counterparts, companies are minimum energy creatures and want to maximize reward (profit) with minimum effort (expense) and will continue to leverage successful lines of evolution until it senses diminishing returns.

The diminishing returns are a warning sign that the company is approaching an edge condition (a Petri dish of a finite size). In landscape lingo, there’s a cliff on the horizon. In technology lingo, the rate of improvement of the technology is slowing. In either language, the edge is near and it’s time to evolve in a new direction because this current one is out of gas.

Like the bird whose mass increases over the generations when food is readily available, companies also get fat and slow when they successfully evolve in a single direction for too long. And like the bird, they get eaten by a more agile competitor/predator. And just as the replication rate of the bacterium accelerates as the food in the Petri dish approaches zero, a company that doesn’t react to a slowing rate of technological improvement is sure to outlive its business model.

Biology and technology are similar in that they try new things (create variants of themselves) in order to live another day. But there’s a big difference – where biology is blind (it doesn’t know what will work and what won’t), technology is sighted (people that create use their understanding to choose the variants they think will work best). And another difference is that biological evolution can build only on viable variants where technology can use mental models as scaffolds to skip non-viable embodiments to cross a chasm.

There’s no need to fall off the cliff. As a leading indicator, monitor the rate of improvement of your technology. If its rate of improvement is still accelerating, it’s time to develop the next line of evolution. If its rate is declining, you waited too long. It’s time to double down on two new lines of evolution because you’re behind the curve. And remember, like with the population of bacteria in the Petri dish, sales will keep growing right up until the business model runs out of food or a competitor eats you.

Image credit — Amanda

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski