Archive for September, 2009

Innovation – words and actions

I sat down to write my weekly post with the hope of coming up with something meaningful on innovation. Nothing came. I asked the all-powerful oracle named Google for some guidance, and my thinking diverged. I realized that there are too many definitions for the word innovation, too many contexts, too many facets. There is too much written about the word and too little written about the actions. I, too, am guilty of using the word for its multiple meanings and sex appeal. I put it in the title of this post to get some attention (I’ll let you know if Google Analytics reports more hits). Heck, I even use the word in the description of the blog.

When I started writing my dissertation, Chris Brown, my advisor, handed me a book and said something like, “You should learn how to write, so read this”. The book was Language In Thought and Action, by S.I. Hayakawa. I read it, finished my dissertation, and, most importantly, learned about words. Since my struggle with innovation was all about the word, I dusted off Hayakawa and asked him to help. Here is what the senator had to say.

To map meaning to a word it is best to point to the physical world (extensional meaning). Putting your hand over your mouth and pointing to a chair is a good way to assign meaning to the word chair. Closing your eyes and talking about a chair (intensional meaning) is not as good. So, to understand innovation it would be best to point your finger at it. But how?

Using an operational definition is a good way to point to the physical world. He quotes physicist P.W. Bridgeman who coined the term.

To find the length of an object, we have to perform certain physical operations. The concept of length is therefore fixed when the operations by which length is measured is fixed….. In general, we mean by any concept nothing more than a set of operations; the concept is synonymous with the corresponding set of operations.”

Hayakawa would ask, “Can you put your hand over your mouth and point to innovation?” Bridgeman would ask, “Can you define the set of operations for innovation? ”

This week my answer is “Not yet”.

Engineering your way out of the recession

Like you, I have been thinking a lot about the recession. We all want to know how to move ourselves to the other side, where things are somewhat normal (the old normal, not the new one). Like usual, my mind immediately goes to products. To me, having the right products is vital to pulling ourselves out of this thing. There is nothing novel in this thinking; I think we all agree that products are important. But, there are two follow-on questions that are important. First, what makes products “right” to move you quickly to the other side? Second, do you have the capability to engineer the “right” products?

Like you, I have been thinking a lot about the recession. We all want to know how to move ourselves to the other side, where things are somewhat normal (the old normal, not the new one). Like usual, my mind immediately goes to products. To me, having the right products is vital to pulling ourselves out of this thing. There is nothing novel in this thinking; I think we all agree that products are important. But, there are two follow-on questions that are important. First, what makes products “right” to move you quickly to the other side? Second, do you have the capability to engineer the “right” products?

The first question – what makes products “right” for these times? Capacity is important to understanding what makes products right. Capacity utilization is at record lows with most industries suffering from a significant capacity glut. With decreased sales and idle machines, customers are no longer interested in products that improve productivity of their existing product lines because they can simply run their idle machines more. And, they are not interested in buying more capacity (your products) at a reduced price. They will simply run their idle machines more. You can’t offer an improvement of your same old product that enables customers to make their same old products a bit faster and you can’t offer them your same old products at a lower price. However, you can sell them products that enable them to capture business they currently do not have. For example, enable them to manufacture products that their idle machines CANNOT make at all. To do that means your new products must do something radically different than before; they must have radically improved functionality or radically new features. This is what makes products right for these times.

On to the second question – do you have the capability to engineer the right products? Read the rest of this entry »

Out of the recession — top line or bottom line approach?

I have been watching the news and listening to the pundits, and, apparently, we are steaming out of the great recession and the manufacturing flywheel is nearing full speed.

I have been watching the news and listening to the pundits, and, apparently, we are steaming out of the great recession and the manufacturing flywheel is nearing full speed.

As we all know, that’s a bunch of crap. Many manufactures are still in survival mode where cost cutting has crossed into the ridiculous; where the best talent has been cut; and where the product development flywheel is motionless. We are far from coming out of this thing, and the bad stuff we had to do to survive will take time to undo.

However, some companies are considering options to accelerate themselves out of the soup. They are asking the big question – what is the fastest way out?

To me, the fastest way out is all about three things: product, product, product — do you have the right products coming to market? Or, if not, how can you get your product development flywheel moving so the right products hit the market as quickly as possible? But, what are the attributes of the “right product”?

I think there are two components of the right product: the top line component and the bottom line component. The top line component (which drives top line growth) is all about function and features. More function equals increased sales through market share and price. The bottom line component (bottom line growth) is all about cost. Pretty basic. But, if your resources are limited (like most of us) and can improve only one, which should you improve?

Bottom line cost reduction is not glamorous, but the balance sheet improvment is surprisingly good. Let me give an example. Product A is an existing product that sells for $1000 and it costs you $800 to produce, providing $200 profit per unit. You spend your product development resources on a bottom line effort and reduce product cost by 20%. Still selling for $1000 but with a cost of $640 (0.8 * $800), profit dollars increase by 80% ($360 vs. $200). Not bad especially since sales have not increased.

Top line growth has a strong emotional component which energizes people, and the upside potential is huge. Here is an example using the same product as above. Product A still sells for $1000, costs you $800, and you make $200 per unit. You spend your product development resources on a top line project to add better functionality and more features. Because you don’t have time to address the bottom line component, your costs go up 10% (to $880). But, you do get the function and features you wanted, and the market can support a 10% price increase to $1100. Profit per unit is up 10% t0 $220 ($1100 – $880). Your engineering really came through and the market likes your new product and sales increase by 20%. With all that, profit dollars increase by 32% ($220*1.2 = $264 vs. $200).

Clearly the examples are contrived to illustrate a point: bottom line cost reduction is powerful and so are top line sales growth and price increase. And the best answer is not to choose between top line and bottom line components. It makes a lot of sense to do a little of both, because it’s the fastest way out of the soup.

Can CEOs meaningfully guide technology work?

Leading, shaping, and guiding technology work is hard, even for technologists who spend all day doing it. So, it seems the all-too-busy CEOs don’t stand a chance at effectively shaping their companies’ technical work. And it’s not just the non-technologist CEOs who have a problem; the technologist CEOs also have a problem, as they don’t have sufficient time to dig deeply into the details or stay current on the state-of-the-art. So, as a CEO, technologist or not, it is difficult to meaningfully lead, shape, and guide technical work.

Leading, shaping, and guiding technology work is hard, even for technologists who spend all day doing it. So, it seems the all-too-busy CEOs don’t stand a chance at effectively shaping their companies’ technical work. And it’s not just the non-technologist CEOs who have a problem; the technologist CEOs also have a problem, as they don’t have sufficient time to dig deeply into the details or stay current on the state-of-the-art. So, as a CEO, technologist or not, it is difficult to meaningfully lead, shape, and guide technical work.

So why is this technology stuff so hard to shape and guide? Well, here are a few reasons: technologies have their own set of arcane languages, each with many dialects (and no dictionary); they have their own technology-centric acronyms that technologists mix and match as they see fit; and they are full of long-forgotten formulae. And these formulae are composed of strange math shapes and symbols. And, as if to elevate confusion to stratospheric levels, the math symbols are Greek letters. So, literally, this technology stuff is written in Greek. So what’s an all-too-busy CEO to do? Read the rest of this entry »

Assess Design Alternatives With Axiomatic Design

Al Hamilton, of Axiomatic Design Solutions, wrote a good article on how Axiomatic Design can be used to evaluate multiple design alternatives.

Here is an excerpt from the article:

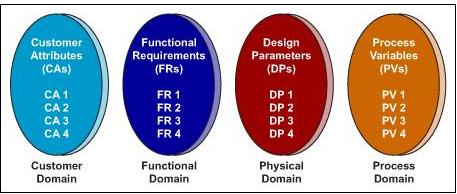

Axiomatic design breaks the design process into four domains, shown in Figure 1. The customer domain can be thought of as the voice of the customer (VOC).

- The functional domain is initially populated by mapping the VOC into independent measurable functions. High-level functions are driven by the customer; lower-level functions are driven by design choices. Every function must be measurable.

- The physical domain is the domain of physics, chemistry, math and algorithms.

- The process domain is where the specifics of how the design parameters identified in the physical domain will be implemented.

Dr. Mike Shipulski, director of engineering at Hypertherm, a manufacturer of plasma cutting systems, has made extensive use of axiomatic design. Shipulski observes, “By first defining the functions we are to achieve, we align our problem solving on the right areas and broaden possible design opportunities. With axiomatic design, we have a framework for avoiding problems that are often detected only during system-level testing.”

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski