Posts Tagged ‘Trust-based approach’

Everyday Leadership

What if your primary role every day was to put other people in a position to succeed? What would you start doing? What would you stop doing? Could you be happy if they got the credit and you didn’t? Could you feel good about their success or would you feel angry because they were acknowledged for their success? What would happen if you ran the experiment?

What if your primary role every day was to put other people in a position to succeed? What would you start doing? What would you stop doing? Could you be happy if they got the credit and you didn’t? Could you feel good about their success or would you feel angry because they were acknowledged for their success? What would happen if you ran the experiment?

What if each day you had to give ten compliments? Could you notice ten things worthy of compliment? Could you pay enough attention? Would it be difficult to give the compliments? Would it be easy? Would it scare you? Would you feel silly or happy? Who would be the first person you’d compliment? Who is the last person you’d compliment? How would they feel? What could it hurt to try it for a week?

What if each day you had to ask five people if you can help them? Could you do it even for one day? Could you ask in a way the preserves their self-worth? Could you ask in a sincere way? How do you think they would feel if you asked them? How would you feel if they said yes? How about if they said no? Would the experiment be valuable? Would it be costly? What’s in the way of trying it for a day? How do you feel about what’s in the way?

What if you made a mistake and you had to apologize to five people? Could you do it? Would you do it? Could you say “I’m sorry. I won’t do it again. How can I make it up to you?” and nothing else? Could you look them in the eye and apologize sincerely? If your apology was sincere, how would they feel? And how would you feel? Next time you make a mistake, why not try to apologize like you mean it? What could it hurt? Why not try?

What if every day you had to thank five people? Could you find five things to be thankful for? Would you make the effort to deliver the thanks face-to-face? Could you do it for two days? Could you do it for a week? How would you feel if you actually did it for a week? How would the people around you feel? How do you feel about trying it?

What if every day you tried to be a leader?

Image credit – Pedro Ribeiro Simões

The Leader’s Journey

If you know what to do, do it. Don’t ask, just do.

If you know what to do, do it. Don’t ask, just do.

If you’re pretty sure what to do, do it. Don’t ask, just do.

If you think you may know what to do, do it. Don’t ask, just do.

If you don’t know what to do, try something small. Then, do more of what works and less of what doesn’t.

If your team doesn’t know what to do unless they ask you, tell them to do what they think is right. And tell them to stop asking you what to do.

If your team won’t act without your consent, tell them to do what they think is right. Then, next time they seek your consent, be unavailable.

If the team knows what to do and they go around you because they know you don’t, praise them for going around you. Then, set up a session where they educate you on what you should know.

If the team knows what to do and they know you don’t, but they don’t go around you because they are too afraid, apologize to them for creating a fear-based culture and ask them to do what they think is right. Then, look inside to figure out how to let go of your insecurities and control issues.

If your team needs your support, support them.

If your team need you to get out of the way, go home early.

If your team needs you to break trail, break it.

If they need to see how it should go, show them.

If they need the rules broken, break them.

If they need the rules followed, follow them.

If they need to use their judgement, create the causes and conditions for them to use their judgement.

If they try something new and it doesn’t go as anticipated, praise them for trying something new.

If they try the same thing a second time and they get the same results and those results are still unanticipated, set up a meeting to figure out why they thought the same experiment would lead to different results.

Try to create the team that excels when you go on vacation.

Better yet, try to create the team that performs extremely well when you’re involved in the work and performs even better when you’re on vacation. Then, because you know you’ve prepared them for the future, happily move on to your next personal development opportunity.

Image credit — Puriri deVry

Allocating resources as if people and planet mattered.

Business is about allocating resources to achieve business objectives. And for that, the best place to start is to define the business objectives.

Business is about allocating resources to achieve business objectives. And for that, the best place to start is to define the business objectives.

First – what is the timeframe of the business objectives? Well, there are three – short, medium and long. Short is about making payroll, shipping this month’s orders and meeting this year’s sales objectives. Long is about the existence of the company over the next decade and happiness of the people that do the work along the way. And medium – the toughest – is in-between. It’s neither short nor long but bound by both.

Second – define business objectives within the three types: people, planet and profit.

People. Short term: pay them so they can eat, pay the mortgage and fund their retirement, provide healthcare, provide a safe workplace, give them work that fits their strengths and give them time to improve their community. Medium: pay them so they can provide for their family and fund their retirement, provide healthcare, provide a safer workplace, give them work that requires them to grow their strengths and give them time to become community leaders. Long: pay them so they can pay for their kids’ college and know they can safely retire, provide the safest workplace, let them choose their own work, and give them time to grow the next community leaders. And make it easy.

Planet. Short term: teach Life Cycle Assessment, Buddhist Economics and TRIZ and create business metrics for them to flourish. Medium: move from global sourcing to local sourcing, move to local production, move from business models based on non-renewable resources to renewable resources. Long: create new business models that are resource neutral. Longer: create business models that generate excess resources. Longest: teach others.

Profit. Short, medium and long – focus on people and planet and the profits will come. But also focus on creating new value for new customers.

For business objectives, here’s the trick on timeframe – always work short term, always work long term and prioritize medium term.

And for the three types of business objectives, focus on people, planet and creating new value for new customers. Profits are a result.

Image credit – magnetismus

The one good way to change behavior.

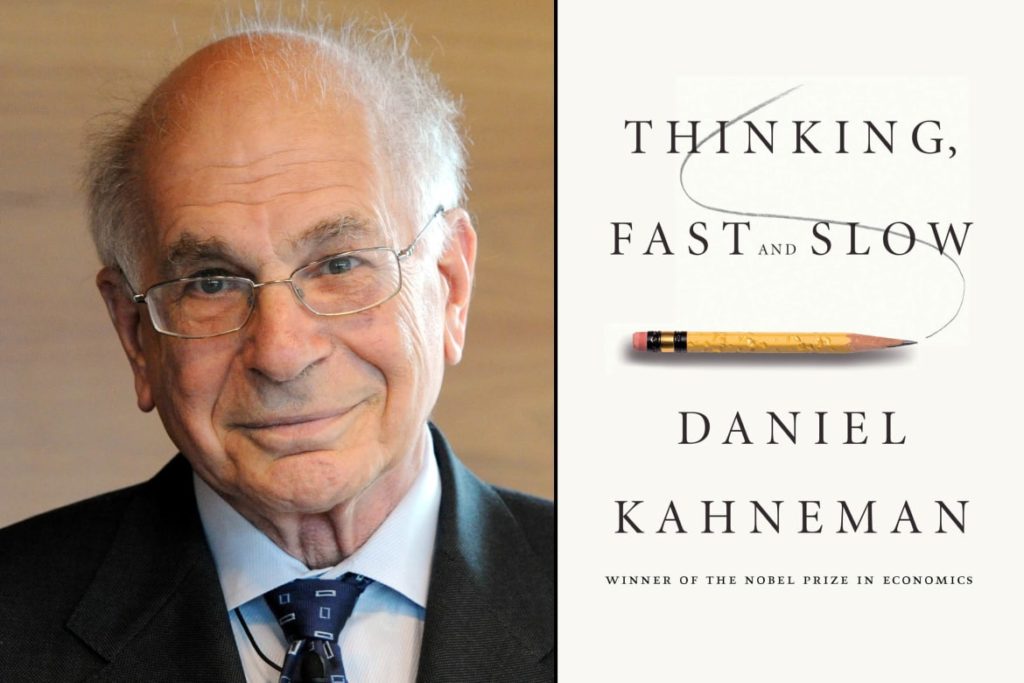

There’s one good way to change behavior. But don’t take my word for it, take Daniel Kahneman’s, psychologist who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences. In Freakonomics Radio’s podcast How to Launch a Behavioral Change Revolution, Kahneman explains how to achieve change in behavior. His explanation is short [30:35 – 35:21] and good.

There’s one good way to change behavior. But don’t take my word for it, take Daniel Kahneman’s, psychologist who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences. In Freakonomics Radio’s podcast How to Launch a Behavioral Change Revolution, Kahneman explains how to achieve change in behavior. His explanation is short [30:35 – 35:21] and good.

Kahneman describes a theory of Kurt Lewin, his academic grandfather, where behavior is an equilibrium, a balance between driving forces that push for change and restraining forces that hold back change. Kahneman goes on to describe Lewin’s insight. “Lewin’s insight was that if you want to achieve change in behavior, there is one good way to do it and one bad way. The good way is by diminishing restraining forces, not by increasing the driving forces. That turns out to be profoundly non-intuitive.”

Usually, when we want someone to change, we push them in the direction we want them to go. Kahneman says this approach is natural, but ineffective. He offers a different approach – “Instead of asking how can I get him or her to do it, it starts with a question of why isn’t she doing it already? Go one-by-one, systematically, and you ask ‘What can I do to make it easier for that person to move?’”

What would happen if instead of pushing someone to change, you understand what’s in the way and eliminated the restraining force? I don’t know, but I’m going to give it a try.

Kahneman goes on to describe how to make things easier for a person to move. He says “…the way to make things easier is almost always by controlling the individual’s environment…by just making it easier.” Sounds pretty simple – change people’s environment to make it easier for them to move toward the desired behavior. But, we don’t do it that way.

Kahneman gives more detail. “Are there incentives that work against it? Let’s change the incentives.” And then he gives a simple example. “I want to influence B, but there is A in the background and it’s A who is a restraining force on B, let’s work on A, not on B.”

I urge you to listen to the short segment to hear Kahneman’s words for yourself. His ideas really hit home when you hear them from him.

Creating the Causes and Conditions for Self Growth – once a week for the last eight years.

With this blog post, I’ve written a blog post every Wednesday night for eight years, with no misses and no repeats.

With this blog post, I’ve written a blog post every Wednesday night for eight years, with no misses and no repeats.

It started while on vacation at a friend’s house where he suggested I write a blog. I had no idea what a blog was or how to write one. I didn’t know that a blog usually sits on a website and I didn’t know how to make a website or even how to pay someone to make one. And once I stopped hiding behind the transactional work, I realized I didn’t know what to write about or how to start.

Right out of the gate I learned that starting is difficult. I was anxious and afraid and I told myself all sorts of scary stories that didn’t come true. As I pushed through the basics of creating a website, there were plenty of opportunities to stop, but I didn’t. There was a force pushing me, and though I didn’t know where it came from I was happy when it woke up with me every morning and stayed by my side.

Before starting I had no website and then I had one. I moved from no to yes. Creating something from nothing feels great when you’re done, but not beforehand. But I wasn’t even done starting.

The first time I faced the blank screen I was paralyzed. I had many ideas and none of them good enough. I wrote and rewrote paragraphs and scrapped them. I wrote whole drafts and scrapped them. I didn’t have the confidence to say what I wanted to say and let people judge my work. What would they say about me? Would they think about me? Do my words make sense? Are they interesting? Are they right?

At some point I got too tired, my resistance weakened and I hit the publish button. I was still afraid, but in a moment of weakness I sent it anyway. Though I catastrophized before sending, nothing bad happened when I sent it. Nothing good happened either, and I was fine with both.

Self-judgment is a powerful blocking mechanism, but I broke through for the first time. Now, going on 416 times, I’ve started with a blank screen, pushed through my self-judgment and wrote a post. It’s easier now, but it’s still not easy. And it won’t be easy next year. In fact, what I learned is the posts that caused the most uneasiness in me made the largest impact on others. I learned if I put my deepest personal thoughts into my writing, others appreciated it. But more importantly, I stood three inches taller after writing it.

With my posts, every week I must to create something from nothing. Every week I must think deeply, distill and write clearly. At the end of every post, I know more about the subject I wrote about. In that way, I can be my own teacher. And every week I must push through my self-doubt and publish. And in that way, every week I create the causes and conditions for self-growth.

Everything gets better with practice. And my practice of starting with nothing and ending with something has helped me be more effective in domains of high uncertainty. I still feel anxious, but I know it won’t hurt me. And now I use my anxiety for good – as a leading indication that I’m working in new design space. And when I don’t feel anxious, I know to stop what I’m doing and work on something else.

Image credit – Steve Jurvetson

Wisdom Within Dichotomy

To create future success, you’ve got to outlaw the very thing responsible for your past success.

To create future success, you’ve got to outlaw the very thing responsible for your past success.

Sometimes slower is faster and sometimes slower is slower. But it’s always a judgement call.

We bite the bullet and run expensive experiments because they’re valuable, but we neglect to run the least expensive thought experiments because they’re too disruptive.

There’s an infinite difference between the impossible and the almost impossible. And the people that can tell the difference are infinitely important.

If you know how to do it, so does your competition. Do something else.

We want differentiation, but we can’t let go of the sameness of success.

People that make serious progress take themselves lightly.

If you can predict when the project will finish, you can also predict customers won’t be excited when you do.

If you don’t have time to work on something, you can still work on it a little a time.

Perfection is good, but starting is better.

Sometimes it’s time to think and sometimes it’s time to do. And it’s easy to decide because doing starts with thinking.

When your plate is full and someone slops on a new project, there may be a new project on your plate but there’s also another project newly flopped on the floor.

New leaders demand activity and seasoned professionals make progress.

Sometimes it’s not ready, but most of the time it’s ready enough.

There’s no partial credit for almost done. That’s why pros don’t start a project until they finish one.

In this age of efficiency, effectiveness is far more important.

Image credit — Silentmind8

Complaining isn’t a strategy.

It’s easy to complain about how things are going, especially when they’re not going well. But even with the best intentions, complaining doesn’t move the organization in a new direction. Sometimes people complain to attract attention to an important issue. Sometimes it’s out of frustration, sometimes out of sadness and sometimes out of fear, but it’s never the best mechanism.

It’s easy to complain about how things are going, especially when they’re not going well. But even with the best intentions, complaining doesn’t move the organization in a new direction. Sometimes people complain to attract attention to an important issue. Sometimes it’s out of frustration, sometimes out of sadness and sometimes out of fear, but it’s never the best mechanism.

If the intention is to convey importance, why not convey the importance by explaining why it’s important? Why not strip the issue of its charge and use an approach and language that help people understand why it’s important? It’s a simple shift from complaining to explaining, but it can make all the difference. Where complaining distracts, explaining brings people together. And if it’s truly important, why not take the time to have a give-and-take conversation and listen to what others have to say? Instead of listening to respond, why not listen to understand?

If you’re not willing to understand someone else’s position it’s not a conversation.

And if you’re on the receiving end of a complaint, how can you learn to see it as a sign of importance and not as an attack? As the receiver, why not strip it of its charge and ask questions of clarification? Why not deescalate and move things from complaint to conversation? Understanding is not agreeing, but it still a step forward for everyone.

When two sides are divided, complaining doesn’t help, even if it’s well-intentioned. When two sides are divided and there’s strong emotion, the first step is to take responsibility to deescalate. And once emotions are calmed, the next step is to take responsibility to understand the other side. At this stage, there is no requirement to agree, but there can be no hint of disagreement as it will elevate emotions and set progress back to zero. It’s a slow process, but when the issues are highly charged, it’s the fastest way to come together.

If you’re dissatisfied with the negativity, demonstrate positivity. If you want to come together, take the first step toward the middle. If you want to generate the trust needed to move things forward, take action that builds trust.

If you want things to be different, look inside.

Image credit – Ireen2005

Companies don’t innovate, people do.

Big companies hold tightly to what they have until they feel threatened by upstarts, and not before. They mobilize only when they see their sales figures dip below the threshold of tolerability, and no sooner. And if they’re the market leaders, they delay their mobilization through rationalization. The dip is due to general economic slowdown that is out of our control, the dip is due to temporary unrest from the power structure change in government, or the dip is due to some ethereal force we don’t yet fully understand. The strength of big companies is what they have, and they do what it takes only when what they have is threatened. But once they’re threatened, watch out. But, the truth is, big companies don’t make change, people within big companies make change.

Big companies hold tightly to what they have until they feel threatened by upstarts, and not before. They mobilize only when they see their sales figures dip below the threshold of tolerability, and no sooner. And if they’re the market leaders, they delay their mobilization through rationalization. The dip is due to general economic slowdown that is out of our control, the dip is due to temporary unrest from the power structure change in government, or the dip is due to some ethereal force we don’t yet fully understand. The strength of big companies is what they have, and they do what it takes only when what they have is threatened. But once they’re threatened, watch out. But, the truth is, big companies don’t make change, people within big companies make change.

Start-ups want to change everything. They reject what they don’t have and threaten the status-quo at every turn. And they’re always mobilized to grow sales. Every new opportunity brings an opportunity to change the game. In a ready-fire-aim way, every phone call with a potential customer is an opportunity to dilute and defocus. Each new opportunity is an opportunity to create a mega business and each new customer segment is an opportunity to pivot. The strength of start-ups is what they don’t have. No loyalty to an existing business model, no shared history with other companies, and no NIH (not invented here). But, once they focus and decide to converge on an important market segment, watch out. But, truth is, start-ups don’t make change, people within start-ups make change.

When you work in a big company, if your idea is any good the established business units will try to stomp it into oblivion because it threatens their status quo. In that way, if your idea is dismissed out of hand or stomped on aggressively, you are likely onto something worth pursuing. If you’re told by the experts “It will never work.” that’s a sign from the gods that your idea has strong merit and deserves to be worked. And this is where it comes down to people. The person with the idea can either pack it in or push through the intellectual inertia of company success. To be clear – it’s their choice. If they pack it in, the idea never sees the light of day. But if they decide, despite the fact they’re not given the tools, time, or training, to build a prototype and show it to company leadership, your company has a chance to reinvent itself. What causes and conditions have you put in place for your passionate innovators to choose to do the hard work of making a prototype?

When you work at a start-up the objective is to dismantle the status quo, and all ideas are good ideas. In that way, your idea will be praised and you’ll be urged to work on it. If you’re told by the experts “That could work.” it does not mean you should work on it. Since resources are precious, focus is mandatory. The person with the idea can either try to convert their idea into a prototype or respect the direction set by company leadership. To be clear – it’s their choice. If they work on their new idea they dilute the company’s best chance to grow. But if they decide, despite their excitement around their idea, to align with the direction set by the company, your startup has a chance to deliver on its aggressive promises. What causes and conditions have you put in place for your passionate innovators to choose to do the hard work of aligning with the agreed upon approach and direction?

When no one’s looking, do you want your people to try new ideas or focus on the ones you already have? When given a choice, do you want them to focus on existing priorities or blow them out of the water? And if you want to improve their ability to choose, what can you put in place to help them choose wisely?

To be clear, a formal set of decision criteria and a standardized decision-making process won’t cut it here. But that’s not to say decisions should be unregulated and unguided. The only thing that’s flexible and powerful enough to put things right is the good judgment of the middle managers who do the work. “Middle managers” is not the best words to describe who I’m talking about. I’m talking about the people you call when the wheels fall off and you need them put back on in a hurry. You know who I’m talking about. In start-ups or big companies, these people have a deep understanding of what the company is trying to achieve, they know how to do the work and know when to say “give it a try” and when to say “not now.” When people with ideas come to them for advice, it’s their calibrated judgement that makes the difference.

Calibrated judgement of respected leaders is not usually called out as a make-or-break element of innovation, growth and corporate longevity, but is just that. But good judgement around new ideas are the key to all three. And it comes down to a choice – do those ideas die in the trenches or are they kindly nurtured until they can stand on their own?

No getting around it, it’s a judgment call whether an idea is politely put on hold or accelerated aggressively. And no getting around it, those decisions make all the difference.

Image credit Mark Strozier

Before you can make a million, you’ve got to make the first one.

With process improvement, the existing process is refined over time. With innovation, the work is new. You can’t improve a process that does not yet exist. Process creation, yes. Process improvement, no.

With process improvement, the existing process is refined over time. With innovation, the work is new. You can’t improve a process that does not yet exist. Process creation, yes. Process improvement, no.

Standard work, where the sequence of process steps has proven successful, is a pillar of the manufacturing mindset. In manufacturing, if you’re not following standard work, you’re not doing it right. But with innovation, when the work is done for the first time, there can be no standard work. In that way, if you’re following the standard work paradigm, you are not doing innovation.

In a well-established manufacturing process, problems are tightly scoped and constrained. There can be several ways to solve it and one of the ways is usually better than the others. Teams are asked to solve the problem three or four ways and explain the rationale for choosing one solution over the other. With innovation it’s different. There may not be a solution, never mind three. With innovation, it’s one-in-a-row solution. And the real problem is to decide which problem to solve. If you’re asked to use Fishbone diagrams to solve the problem three or four ways, you’re not doing innovation. Solve it one way, show a potential customer and decide what to do next.

With manufacturing and product development, it’s all about Gantt charts and hitting dates. The tasks have a natural precedence and all of them have been done before. There are branches in the plan, but behind them is clear if-then logic. With innovation, the first task is well-defined. And the second task – it depends on the outcome of the first. And completion dates? No way. If you can predict the completion date, you’re not doing innovation. And if you’re asked for a fully built-out Gantt chart, you’re in trouble because that’s a misguided request.

Systems in manufacturing can be complicated, with lots of moving parts. And the problems can be complicated. But given enough time, the experts can methodically figure it out. But with innovation, the systems can be complex, meaning they are not predictable. Sometimes parts of the system interact strongly with other parts and sometimes they don’t interact at all. And it’s not that they do one or the other, it’s that they do both. It’s like they have a will of their own, and, sometimes, they have a bad attitude. And if it’s a new system, even the basic rules of engagement are unknown, never mind the changing strength of the interactions. And if the system is incomplete and you don’t know it, linear thinking of the experts can’t solve it. If you’re using linear problem solving techniques, you’re not doing innovation.

Manufacturing is about making one thing a million times. Innovation is about choosing among the million possibilities and making one-in-a-row, and then, after the bugs are worked out, making the new thing a million times. But one-in-a-row must come first. If you can’t do it once, you can’t do it a million times, even with process improvement, standard work, Gantt charts and Fishbone diagrams.

Image credit jacinta lluch valero

Put Yourself Out There

If you put yourself out there and it doesn’t go as you expect, don’t get down. All you are responsible for is your effort and your intentions. You’re not responsible for the outcome. Intentions don’t drive outcomes. In fact, be prepared for your work to bring out the opposite of your intentions.

If you put yourself out there and it doesn’t go as you expect, don’t get down. All you are responsible for is your effort and your intentions. You’re not responsible for the outcome. Intentions don’t drive outcomes. In fact, be prepared for your work to bring out the opposite of your intentions.

If you put yourself out there and it goes poorly, don’t judge yourself negatively. Sometimes, things go that way. It’s not a problem, unless you make it one. So, don’t make it one. Just put yourself out there.

The clothes don’t get clean without an agitator. Hold onto that, and put yourself out there.

How do you know you’ve put yourself out there? The status quo is angry with you. The people in power want you to stop. The organization tries to scuttle your work. And the people that know the truth take you out to lunch.

If you put yourself out there and your message is met with 100% agreement, you didn’t put yourself out there. You may have stepped outside the lines, but you didn’t put your whole self on the line. You didn’t splash everyone with a full belly flop. There wasn’t enough sting and your belly isn’t red enough.

You won’t get it right, but put yourself out there anyway. You can’t predict the outcome, but take a run at the status quo. You don’t know how it will turn out, but that’s not a reason to hold back, it’s objective evidence it’s time to take a run at it.

Don’t put yourself out there because it’s the right thing to do, put yourself out there because you have an emotional connection. Put yourself out there because it’s time to put yourself out there. Put yourself out there because you don’t know what else to do.

Be prepared to be misunderstood, but put yourself out there. Expect to be laughed at and talked about behind your back, but put yourself out there. And expect there will be one or two people who will have your back. You know who they are.

No sense holding back. Get over the fear and put yourself out there.

The only one holding you back is you.

Image credit – Mark Bonica

Dismantle the business model.

When companies want to innovate, there are three things they can change – products, services and business models. Products are usually the first, second and third priorities, services, though they have a tighter connection with customer and are more lasting and powerful, sadly, are fourth priority. And business models are the superset and the most powerful of all, yet, as a source of innovation, are largely off limits.

When companies want to innovate, there are three things they can change – products, services and business models. Products are usually the first, second and third priorities, services, though they have a tighter connection with customer and are more lasting and powerful, sadly, are fourth priority. And business models are the superset and the most powerful of all, yet, as a source of innovation, are largely off limits.

It’s easy to improve products. Measure goodness using a standard test protocol, figure out what drives performance and improve it. Create the hard data, quantify the incremental performance and sell the difference. A straightforward method to sell more – if you liked the last one, you’re going to like this one. But this is fleeting. Just as you are reverse engineering the competitors’ products, they’re doing it to you. Any incremental difference will be swallowed up by their next product. The half-life of your advantage is measured in months.

It’s easy for companies to run innovation projects to improve product performance because it’s easy to quantify the improvement and because we think customers are transactional. Truth is, customers are emotional, not rational. People don’t buy performance, they buy the story they create for themselves.

Innovating on services is more difficult because, unlike a product, it’s not a physical thing. You can’t touch it, smell it or taste it. Some say you can measure a service, but you can’t. You can measure its footprints in the sand, but you can’t measure it directly. All the click data in the world won’t get you there because clicks, as measured, don’t capture intent – an unintentional click on the wrong image counts the same a premeditated click on the right one. Sure, you can count clicks, but if you can’t count the why’s, you don’t have causation. And, sure, you can measure customer satisfaction with an online survey, but the closest you can get is correlation and that’s not good enough. It’s causation or bust. You’ve got to figure out WHY they like your services. (Hint – it’s the people who interface directly with your customers and the latitude you give them to advocate on the customers’ behalf.)

Where services are difficult to innovate, the business model is almost impossible. No one is quite sure what the business model actually is an in-the-trenches-way, but they know it’s been responsible for the success of the company, and they don’t want to change it. Ultimately, if you want to innovate on the business model, you’ve got to know what it is, but before you spend the time and energy to define it, it’s best to figure out if it needs changing. The question – what does it look like when the business model is out of gas?

If you do what you did last time and you get less in return, the business model is out of gas.

Successful models are limiting. Just like with the Prime Directive, where Captain Kirk could do anything he wanted as long as he didn’t interfere with the internal development of alien civilizations, do anything you want with the business model as long as you don’t change it. And that’s why you need external help to formally define the business model and experiment with it. The resource should understand your business first hand, yet be outside the chain of command so they can say the sacrilegious things that violate the Prime Directive without being fired. For good candidates, look to trusted customers and suppliers.

To define the business model, use a simple block diagram (one page) where blocks are labelled with simple nouns and arrows are labelled with simple verbs. Start with a single block on the right of the page labelled “Customer” and draw a single arrow pointing to the block and label it. Continue until you’ve defined the business model. (Note – maximum number of blocks is 12.) You’ll be surprised with the difficulty of the process.

After there’s consensus on the business model, the next step is to figure out how the environment changed around it and to identify and test the preferred evolutionary paths. But that’s for another time.

Image credit – Steven Depolo

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski